.220 Weatherby Rocket

The Improved .220 Swift

feature By: Stan Trzoniec | October, 25

Wildcats have a certain appeal that seems to grab the attention of dedicated riflemen. I like to use what most call an improved version – use of a standard cartridge that is fireformed in the wildcat chamber. A perfect example of this would be the .22 K-Hornet (blown out from the parent .22 Hornet) or the .218 Mashburn Bee that is formed from the .218 Bee. Still another one is the .220 Weatherby Rocket. Firing factory .220 Swift in the Rocket chamber results in the “improved” version with little effort.

The .220 Weatherby Rocket was the first effort by Roy Weatherby in his quest for high-powered proprietary cartridges. While the non-belted Rocket is based on the .220 Swift, others in his stable, like the .224, .240, .257 and the .300 Weatherby Magnum, represent belted cartridges that evolved from ballistic experiments conducted over the years.

With that as a base, let’s turn the clock back to 1935, when Winchester introduced the high-stepping .220 Swift. It vaulted out of factory barrels at over 4,000 fps. Such velocities were unheard of and, of course, with progress comes debate. Rumors of barrel wear flourished and may have been truthful to a point, but if one looks closer, many of the problems might have been prevented. You have to remember at that time – even my uncle was at fault – cleaning a barrel was not at the top of anyone’s list, especially if the rifle was going right back on the pegs in the barn after a shooting session. Metallurgy was almost witchcraft when it came to bullet jackets and combined with the lack of maintenance may have been the chief culprit of why Swift barrels were wearing out; certainly it was a contributing factor.

Overall the Swift was a good, solid cartridge, but its reputation for eroding barrels pretty much discouraged anyone from attempts to match it, except for Roy Weatherby. According to Dean Rumbaugh at Weatherby, Roy started development on the Rocket between 1942 and 1944, finally commercializing it in 1945.

At first it would have seemed like a good move. Since the Swift was stalling out, he could take the same platform, improve its efficiency and offer another choice in rifles. It did give Weatherby a great start, but with the .224 Weatherby Magnum hiding in the wings and due out with a new, shortened rifle, the .220 Weatherby Rocket was doomed. Over the years I’ve seen a slight resurgence in the Rocket, but you have to be a big fan of .22-caliber rifles to consider building a rifle for this cartridge.

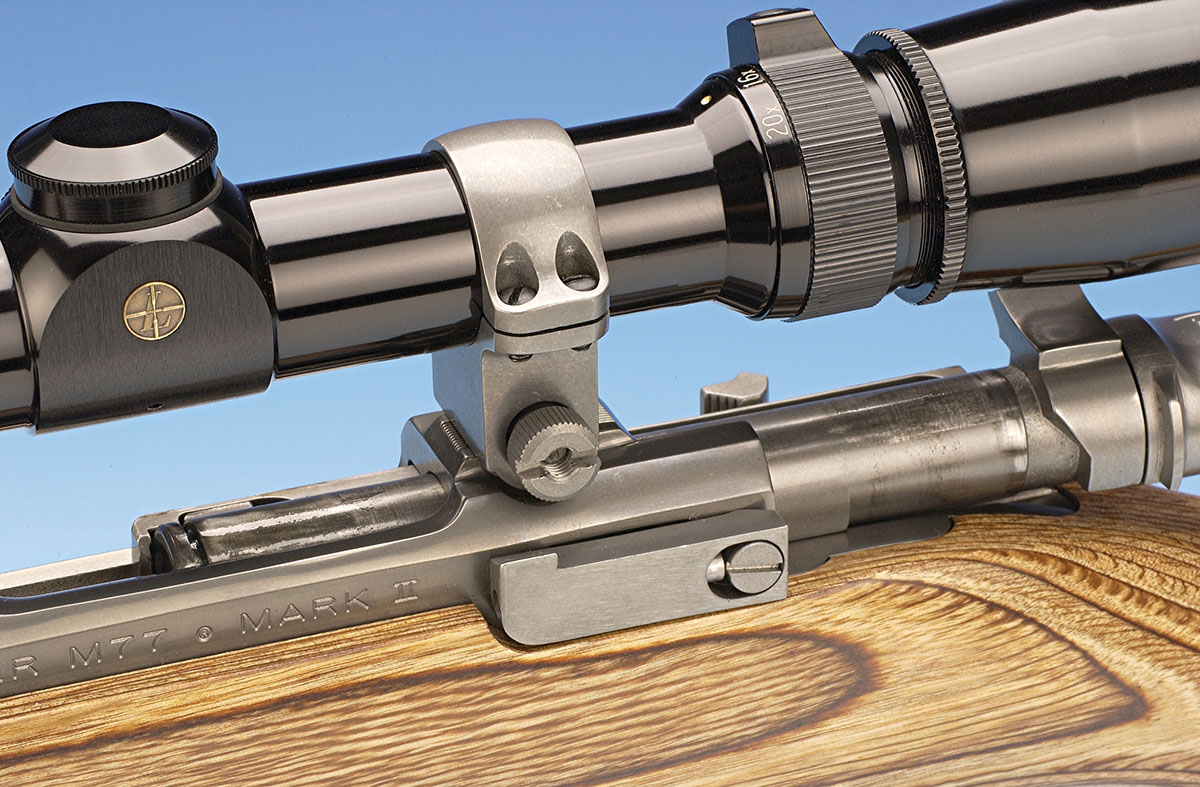

In the quest for a .220 Weatherby Rocket, I pulled a recently purchased Ruger Model 77 MKII (Target) .220 Swift from the rack. For varmint or small game, this is one of Ruger’s hidden treasures. Touted as a Palma-inspired, long-range rifle, this particular model has many desirable features. One I am really fond of is the two-stage trigger that allows a shooter to almost call his shots. When the rifle is cocked, pulling the trigger back about .25 inch places it at the beginning of the second stage. With a slight movement to the rear, the sear breaks at exactly 3 pounds without any hint of creep.

The rifle comes with a varmint-styled, laminated stock sans checkering with a straight comb. The forearm is widened for a stable rest in the field, and the pistol grip has an open curve. The action is pure Ruger, finished in a proprietary gray. The one-piece bolt, complete with a non-rotating extractor, is patterned after the Mauser design. To squeeze the most from the Rocket, the medium-heavy barrel is 26 inches long.

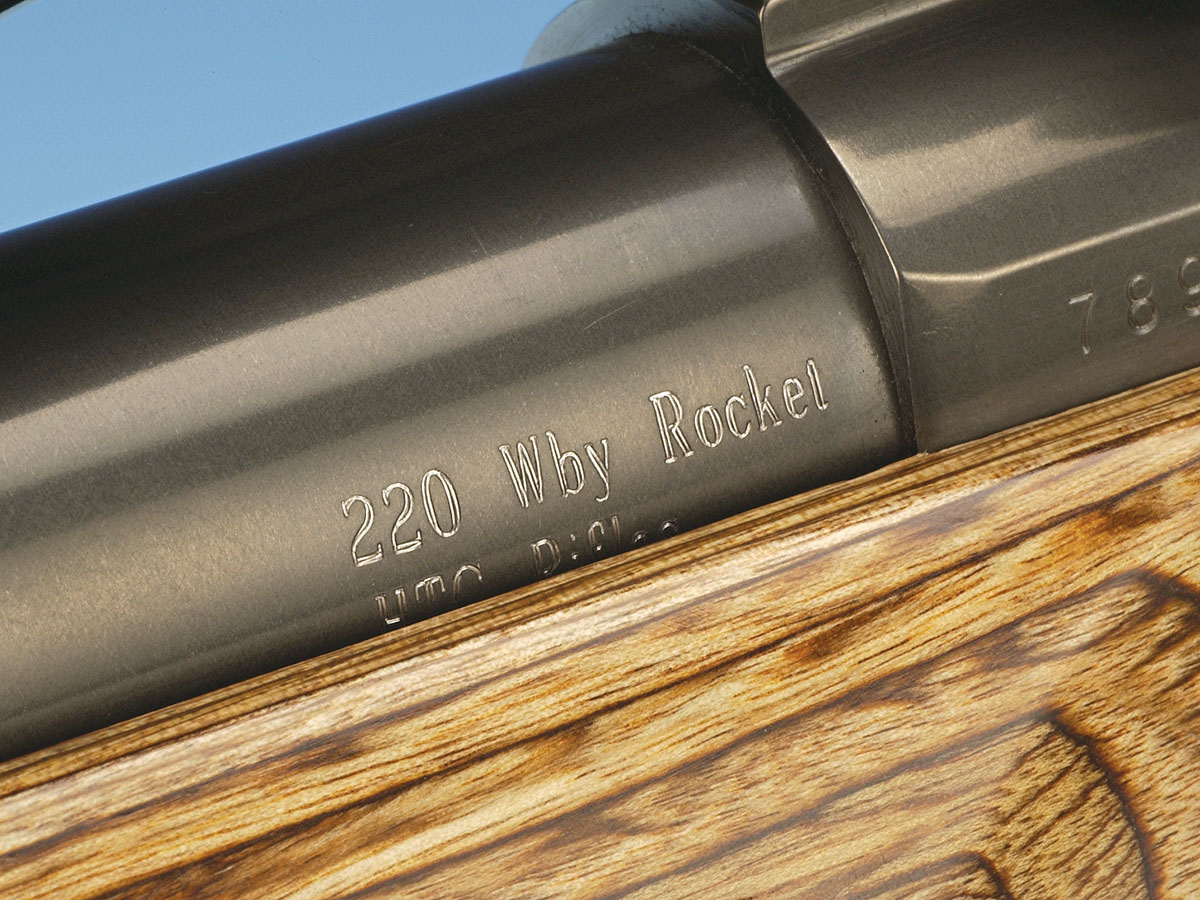

For the conversion, I shipped the rifle to Rich Reiley at High Tech Custom Rifles (3109 N. Cascade, Colorado Springs CO 80907). Since the Rocket is simply an improved .220 Swift, Rich assured me all he would have to do to accommodate the new cartridge would be to recut the chamber and set the barrel back, maybe a full turn. Cost of the conversion with a .220 Swift rifle was $125 plus the shipping. To complete the project, I mounted a Leupold 6.5-20x AO scope in Ruger rings. With the scope I added a 6-inch lens shade (a 2- and 4-inch extension) to help control summer mirage.

The next step was easy; 100 rounds of Remington .220 Swift factory loads with the 50-grain softpoint were fired. (I can always shoot more if warranted.) Naturally, if you have .220 Swift brass, standard handloads will do for fireforming.

Surprisingly, only two cases split. Both were from an older lot of Remington ammunition that had been sitting on the shelf for quite some time. Forty cases from that lot were then segregated from the rest to see if anything else would develop during extended handloading sessions. Nothing ever did, so I dismissed these two examples as aberrations. Cases that came out of the rifle were free of marks or flaws that may appear from reamer chatter in the chamber.

Back at the loading bench, I employed the use of the RCBS 55010 .220 Rocket neck sizer. Since there was just a hint of the Weatherby venturi shoulder on this first cartridge, the neck sizer only advanced to where the curve of the shoulder met the neck. Marking the case with a visible indicator (lipstick, candle soot, soft marker) showed this pro-gress while keeping the integrity of the overall case. I full-length size if the shoulder creeps forward enough to impede loading or chamber fit. Inside neck diameter after firing was .223 inch; after neck sizing only, it was reduced to .219 inch.

Comparing the Rocket to the Swift, we find that the former has a case capacity in water of 50.06 grains. The Swift has a boiler room of 48.0 grains, which is more than enough for the right powder to boost velocities over the 4,000-fps mark. Case observations show that just below the shoulder the outside diameter of the Swift is .402 inch while the Rocket opens up to .427 inch. Further comparisons show the Rocket has its shoulder moved forward by .075 inch, thereby adding to its total internal volume.

Finding data on the Rocket is difficult, especially since it’s long past being front-page news. A call to Weatherby produced one page of data from a vintage copy of Tomorrow’s Rifles Today, a promotional booklet published by Weatherby in years past. A much faster way to find important information is to get a copy of Wayne Blackwell’s “Load From A Disc” ballistic program. After loading the CD in your computer, a full set of options appears. To start, click on “Internal,” select a rifle cartridge (standard, wildcat and custom are included), then hit .220 Weatherby Rocket. Case capacity in grains of water, overall cartridge length (with bullet) and a drawing of the case appear on the screen.

Next, click on “Rifle Load,” and a screen comes up with a profile of the case. Select bullet diameter (.224 inch) and choose from just about every bullet manufacturer today. For an example, I picked the Hornady 50-grain V-MAX and transferred it to my present rifle load. Finally I added the barrel length, the powder (in this case H-4895) and up came the loads, pressure data and estimated velocities. Once familiar with the workings of the program, the process goes quickly, and within a short period of time, it’s easy to amass quite a listing of loads complete with all the relevant data you need to start loading the .220 Rocket.

Still other references like the F.C. Ness tome titled Practical Dope on the .22 revealed quite a bit of data in a very small space. Ness goes on to say (my interpretation now) that Weatherby went through a lot of trouble in an effort to engineer and/or improve the already em-bedded .220 Swift. He also takes note that because of Weatherby’s

insistence of a straighter 30-degree shoulder, he could increase the powder charge without raising pressure to any measurable degree. It seems right here that Roy Weatherby was onto something that for all practical purposes was the innocent beginnings of his venturi-based or double-radius shoulder design. Finally, it’s also quite ironic that the load data supplied by the Weatherby firm in its house catalog matches that of F.C. Ness and his recommendations within the pages of his book.

Phil Sharpe also had his input into the .220 Rocket program with some reservations. He pats Roy on the back for his “more rounded curves [on the case] which he [Weath-erby] believes produces more efficient powder combustion.” Sharpe goes on with some testing using both Swift ammunition fired in a Weatherby chamber and formed cases for a comparison. The results were very close. Sharpe does state the end results were compiled with Remington brass; Winchester brass, being somewhat heavier in weight, needed a slight reduction in powder charges.

I did use loads from the Weatherby history files, some from the Ness book and other relevant data saved over the years and most of the remaining from the “Load From A Disc” program. Powders were right in line with what a cartridge of this type would use, and Winchester Large Rifle primers were used in all test loads. Over the years I’ve found these specific Winchester primers were perfect in some cartridge cases where you were walking the fence between using either standard or magnum primers in medium-sized cartridges like the Swift or the Rocket.

Overall the Rocket is no different to load than any other cartridge. Attention to the details like neck sizing, priming and accurate powder measurement result in groups that anyone would be proud of. For neck sizing I place some case lube between my fingers and rub it around the neck, being careful not to get any on the shoulder area. While the die does not come in contact with the shoulder, too much lube within the die and under compression can result in unsightly case dents that could, in the long run, substantially weaken the case. While some of the powders were easy to measure (H-380, W-760) without trickling for volume loading, others like IMR-4064 had to be trickled to bring each charge up to the projected level.

Out on the range, all three-shot groups were fired from the magazine to simulate field conditions. In practical use, however, I would use the rifle as a single shot, since rarely can I load fast enough to shoot at a woodchuck a second time as he hightails it to his den. The flat forend keeps the rifle on target, the overall weight makes shooting a joy, and the target-styled trigger is perfect for this type of small game hunting. During my foray I let the barrel cool for 5 minutes between volleys, and because of its heavy barrel configuration, it was just warm to the touch throughout the entire session. All groups were fired at 100 yards over an Oehler Chronotach. You’ll notice that I’ve included the estimated velocity that came from my sources as a comparison to the actual ve-locity the load delivered out of the 26-inch Ruger.

In looking at the results, the Rocket is indeed a sub-minute-of-angle (MOA) cartridge with some exceptions, which is why we handload. To get one or two loads that fit your needs is a gift; more is even better, as it allows you to switch bullets depending upon the weather, game or distance.

For instance, the Barnes bullets in load 1 (see table) surpassed the 4,000-fps mark, but accuracy was nearly within the 2-inch range. The 50-grain Hornady V-MAX taken from the Blackwell program went over the same velocity marker and accuracy started to improve. Both Speer bullets in the lighter weights went under an inch with a lower velocity. Out of the two, I’d pick load 3, as it is as close to 4,000 fps as possible, yet delivers ex-cellent groups. For those who hunt in a confined area, the load with 43.0 grains of W-760 produces sub-MOA groups with just over 3,600 fps.

For load 5, the Blackwell program suggested 42.0 grains of IMR-4320 would develop 3,906 fps, yet another source showed 4,050 fps. Over the screens the actual velocity showed up at 4,095 fps with groups just over an inch. Inspecting the cartridge, there were no apparent signs of pressure, so I moved on to 43.0 grains of IMR-4320. Here Blackwell’s chart suggested the velocity would be in the neighborhood of 4,132 fps, which in reality was 4,177 fps. With a slight cratering of the primer, this to me would be maximum for my rifle.

Modern technology is impressive, and with the Speer hollowpoint boat-tail and 42.9 grains of W-760 (load 7), references suggested 3,990 fps. Groups were under an inch with a much lower velocity of 3,652 fps, again perfect for close-in targets in between hedgerows. Load 8 shot about 2 inches from my previous point of aim proving that even though the load was indeed accurate, the need to rezero the rifle with every change of load was apparent.

Loads 9, 10 and 11 proved uneventful and all delivered good groups with the exception of the Hornady 55-grain V-MAX, which was exceptional. The one thing I did gather from all my research was that Mr. Weatherby was fond of the heavier 55-grain bullet for this cartridge. His theory, I’m sure, was that with the improved cartridge and added velocity he could justify a heavier bullet at longer ranges when it came to medium game like a fox or coyote. Even though the Hornady came just under the 4,000-fps mark, it is my pick for an overall efficient load in the .220 Rocket.

The next group of loads proved that as handloaders we have to keep track of loads as they are fired. Loads 12 and 13 came from the Ness and Weatherby books, and while they might have been fine in the test barrels in those days, pressure signs were growing with both. Regarding load 12 with 44.0 grains of IMR-4064, both references suggested velocities of 4,072 fps with mediocre groups. The Oehler registered almost 4,200 fps, which on the first volley was okay with just a bit of cratering on the primer. On unlucky 13, the first round produced some disturbing blowback (a good reason to wear glasses), and when I pulled my head back from the stock, a trace of smoke was wafting around the bolt shroud itself. A more than substantial bolt lift was causing concern, and upon ejecting the cartridge, I saw the primer was blown from the case. The reference suggested the velocity was around 4,188 fps, and I’m not even going to tell you what the actual velocity was. Forty-four grains of IMR-4064 is plenty, and for a beginning load I’d opt for 42.0 to 43.0 grains.

Still another pair of loads, 14 and 15 came from both the Weatherby and Sharpe books. With 44.0 grains of IMR-4320, the Sierra bullet drop-ped groups consistently into 1⁄2 inch. At just over 4,200 fps, the load in my estimation is hot as velocity goes but still within visual and normal pressure signs. Load 15 was again too hot; no blown primers but extreme cratering on the primer on the first go-round dropped this load from my favorite list fast.

After that, things went back to normal. IMR-4350 and H-4831sc produced groups that were just over MOA with velocities that moved close to 4,000 fps. On average, if

I had my druthers, powder choice would be limited to H-380 and IMR-4320 in the Ruger. Individual rifles might respond differently.

Like always, shooting an “improved” wildcat like the .220 Weatherby Rocket proved to be a challenge. From finding that just-right rifle to be converted, to research and final shooting, my working with this cartridge is not over. There are some gaps to be filled, and I might want to try some other powders and bullets. But for the time being, I did up the ante in velocity over the Swift with good accuracy to boot.

For those veteran handloaders so inclined, I would recommend the .220 Weatherby Rocket as a good wildcat to start out. Check references carefully and work up to what you think is maximum in your rifle, and you’ll be in for a great ride.

.jpg)