.243 WSSM

Short, but High on Performance

feature By: John Haviland | October, 25

Since Winchester’s .243 Super Short Magnum (WSSM) was introduced in 2003, it has been a slow but steady seller. However, at least one handloader out there is enamored with the .243 WSSM, because he called the headquarters of Handloader magazine and demanded a handloading article on the cartridge or he was going to cancel his subscription. So the following is for you, oh squeaky wheel.

The Case for the Super Short

The squat case of the .243 WSSM looks like a regular Winchester Short Magnum case cut off to a length of 1.670 inches. The result is the super short magnum case has a very thick web, walls and neck. The neck rim diameter of the .243 WSSM measures .022 inch, compared to .015 inch for the regular .243 Winchester.

As near as I can determine, a Winchester brand .243 Winchester case holds 52.8 grains of water, a Remington brand 6mm Remington case, 54.3 grains of water and a .243 WSSM case, 54.4 grains of water. Those weights are with the cases filled to the top of the mouth. The .243 WSSM cases are heavy. They weigh 214 grains, which is nearly 40 grains heavier than a 6mm Remington case and nearly 44 grains heavier than a .243 Winchester case. All that brass sits in the web and case walls that look thick as a tomb door.

Many people wonder why Winchester Ammunition would introduce the .243 Winchester Super Short Magnum when the perfectly good .243 Winchester has been so popular for decades. Beats me. Maybe because “new sells.” Whatever the reason, the new .243 has a slight edge in bullet speed over the old .243 and is the velocity twin of the 6mm Remington.

Hodgdon Powder lists maximum loads of about two to seven grains more of various powders in the .243 WSSM than the .243 Winchester. That extra powder gives 70- to 100-grain bullets fired from the short magnum from 70-some to a bit over 140 fps of additional velocity over the .243 Winchester. Hodgdon lists nearly the same powder charges for the 6mm Remington and the .243 WSSM, with both cartridges generating nearly the same bullet speeds.

Winchester Ammunition catalogs its Supreme .243 WSSM loads with a 55-grain Ballistic Silver-tip bullet at 4,060 fps, a 95-grain Ballistic Silvertip at 3,250 fps, a 95-grain XP3 at 3,150 fps and a Super-X 100-grain Power-Point bullet at 3,110 fps. That’s a 150 fps gain with three of the bullets and a 50 fps increase with the XP3 bullet over the old .243 Winchester with the same bullets. Winchester states its 6mm Remington load with a 100-grain Power-Point bullet starts out at 3,100 fps.

When Ron Reiber of Hodgdon Powder developed loads for the .243 WSSM, he found bullet speeds of the .243 super short were much more consistent than the .243Winchester and 6mm Remington. “When you have a short cartridge and a short and wide powder column, you get a more even powder burn,” Reiber said. “The result of that with the .243 super short was much smaller extreme spreads in velocity and lower standard deviation.”

There was a lot of complaining about excessive bore erosion when the .223 and .243 WSSMs were first introduced. This was somewhat unusual because this alleged problem cropped up pretty much before ammunition and rifles had even been on store shelves. Horror stories of bores that looked like corroded sewer pipes after as few as 200 rounds had been fired through them were repeated on the Internet and across gun counters and became gospel. Funny, but such fabrications have never spread about the 6mm Remington. Oh sure, if you sat on the edge of a prairie dog town and fired 500 rounds a day through a .243 WSSM, its bore would be cooked in short order. But the same can be said for the .22-250, .220 Swift and quite a few other cartridges. If you do torch a bore, consider yourself lucky to have the time and money to shoot so much.

But Browning and Winchester firearms took this criticism to heart and have included a chrome-lined bore in all the rifles they have produced in .223 and .243 WSSM. The lining is supposed to double the longevity of the WSSM’s bore.

A fellow from Winchester Ammunition said his Browning A-Bolt chambered in .223 WSSM has had 2,200 rounds fired through it and still groups five shots inside an inch at 100 yards. I like the chrome- lined bore because it’s easy to clean. After firing 150 rounds of .243 WSSM cartridges one day through the Browning A-Bolt Var-mint Stalker used to shoot the loads listed in the load table, I squirted Birchwood Casey Bore Scrubber foaming gel in the bore and left it overnight. The next morning the bore got a good scrubbing with a brush, a few patches to wipe out the gunk, and it was clean. Copper fouling was minimal.

Powder Life

A friend has a keg of H-4831 powder that was most likely manufactured in 1952 and wondered if the powder had deteriorated over the decades. For what it’s worth, the powder’s lot number is ALAR52.

I stuck my nose in the powder container opening and sniffed, like I would a glass of fine port, if I drank such swill. The old powder had a slightly sweet smell, no repulsive acrid odor at all.

I thought the powder was still good, so I loaded 44.5 grains of it with Sierra 100-grain bullets in the .243 WSSM. As the load table shows, the old H-4831 produced an average of 75 fps more velocity than H-4831 that is a few years old. Accuracy of the Sierra bullets was nearly the same with both powders. Extreme spreads of velocity for three, three-shot groups with the old H-4831 ran 13, 24 and 50 fps. The new powder had an extreme spread of 27 fps.

Consequently, if powder is stored in a cool, dry place, it should remain usable for at least 50 years, maybe indefinitely.

In the Field

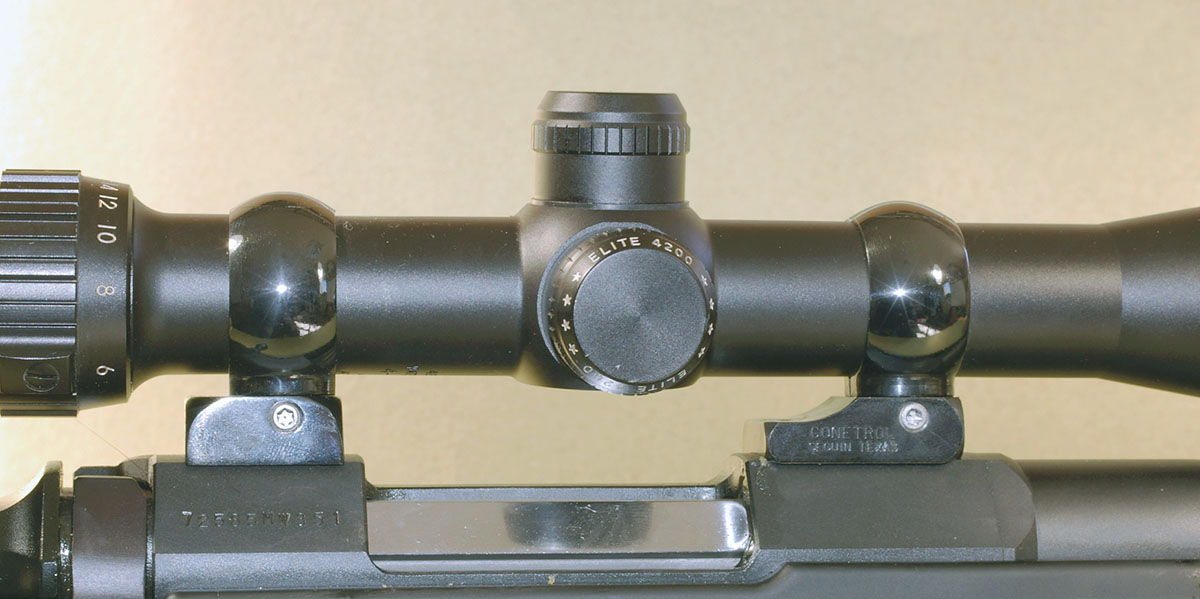

In the fall of 2003, I carried an A-Bolt Hunter in .243 WSSM on a Wyoming prairie dog and pronghorn hunt. The rifle weighed 6 pounds, 4 ounces with its 21-inch barrel. Add a pound for the Kahles 2.5-10x 50mm scope in Talley aluminum rings and the rifle weighed slightly over 7 pounds ready to hunt. That’s a few ounces less weight and 1.5 inches shorter in overall length than the same rifle in a .243 Winchester. A-Bolt Hunter rifles in the super short cartridges wear 22-inch barrels, so the super short’s advantage is reduced to .5 inch.

To tell the truth, hitting prairie dogs way out there wasn’t all that difficult. The Winchester Supreme .243 WSSM ammunition I shot was loaded with 55-grain Ballistic Silvertip bullets. Winchester lists the velocity of these bullets at 4,060 fps at the muzzle of a 24-inch barrel. From the 21-inch barrel of the Browning A-Bolt rifles, the muzzle velocity was 4,035 fps. With the bullets sighted 1.5 inches high at 100 yards, bullet drop was slightly less than 2 inches at 300 yards and a smidgen less than 9 inches at 400 yards.

The prairie dogs were easy to hit, that is until the sun whipped up the wind. By 10 o’clock the wind howled out of the west. Shooting straight across the wind at 200 yards required an aim 6 to 8 inches into the wind to connect with a prairie dog. At 300 yards bullet drift seemed to be at least three prairie dog lengths. Of course, the amount of drift changed depending on the angle of the wind to the shots. After awhile I gave up.

I was ready for a long-range shot at a pronghorn after a day and a half of shooting prairie dogs. I spotted a nice buck and made a short stalk around the side of a low hill. The buck started walking away, and I knelt with the .243 supported by my knee. When the buck stopped, I shot it from 35 yards with a single 95-grain Ballistic Silvertip. The buck ran that much farther and fell over, kicking. So much for a long shot.

Reloading the .243 WSSM

I took a simple, but as it turned out an inconsistent, approach to determining overall loaded cartridge length for the different bullets listed in the load table. Win- chester Supreme Elite cartridges had 95-grain XP3 bullets seated to a depth where the bullets were about .04 inch from contacting the rifling of the Browning .243 WSSM. The Winchester XP3 bullets produced tight groups, so I used a Stoney Point Bullet Comparator to measure the length of the Winchester cartridge from the face of the case head to where the curvature of the ogive of the XP3 came to the full diameter of the bullet. Still using the bullet comparator tool, that length was used to set the seating depths of the other bullets.

As I discovered later, that length set the various bullets of 55 to 105 grains about .077 to .113 inch from contacting the rifling. I would have known that too, if I had read the bullet comparator’s instructions that state, “. . . it is unlikely a comparator will contact the bullet’s ogive in the exact location that the lands will. Therefore, a comparator cannot be used to transfer dimensions from loaded rounds with different bullet models.”

Still, all the bullets shot groups under an inch. (The one exception was the Hornady 105-grain A-MAX that is too long to stabilize in the rifle’s one-in-10-inch rifling twist.) That shows bullets seated straightly in the case neck and aligned with the bore contribute as much, or more, to accuracy as bullets seated next to the rifling. The Redding Competition Bullet Seating Die used to seat bullets certainly helped with that, because cartridges assembled with the die had bullet runouts from nothing to .002 inch.

Handloading the .243 WSSM was straightforward. After factory loaded cartridges were fired, the cases were trimmed. They stretched next to nothing after that, even after being fired as many as five times. No cases were lost because of any type of split at the web or crack on the neck.

Still, the .243 WSSM is a good and useful cartridge. It produces faster bullet speed than the .243 Winchester, and today’s hunters like speed. The super short .243 case is also much stouter and fits better in a shorter action than the 6mm Remington case.

.jpg)