A Brace of .17s

.17 Mach IV Versus the .17 Remington

feature By: Stan Trzoniec | October, 25

Looking back, it’s difficult to pin-point the original idea and intent of the .17-caliber cartridge, never mind the seemingly unending list of variations. Even before the popular .17 Remington was thought of, 55 years ago the legendary Parker Ackley built a .17-caliber rifle for the late C.H. O’Neil. Called the .17 Pee Wee, it was nothing more than the .30 M1 carbine case necked down to .172 inch.

Still the list goes on. The .17 Squirrel is simply another version of the .22 Hornet case with the shoulder pushed back slightly; the .17-221 is an early version of the .17 Mach IV with its shoulder angle moved back. Later, an improved .17 Mach IV somewhat overpowered the original version by incorporating a sharper shoulder angle.

The .17-222 is easily formed by first running the .222 Remington case in a sizing die and finishing the operation by fireforming. There are also additional variations like the .17 Landis Woodsman, .17-40 and .17-32 Jet, obviously formed by necking down the famous .22 Jet cartridge. Much later – over a quarter-century later – the .17 Remington appeared and, much to the chagrin of most, simply and very easily commercialized the .17 caliber.

Newcomers to the .17-caliber family have a couple of options, both of which are easy to work with at the loading bench or in the field. The .17 Remington is a great cartridge, and since it is commercialized, rifles, brass and components are as close as your nearest sporting goods store. On the other hand, folks who enjoy working with wildcats might find the well-liked .17 Mach IV inviting. Both are close in terms of velocity (considering internal volume) with the edge going to the “legalized” Remington brand, but in the end it boils down to whether you’d like to sit back and purchase everything from stock or roll your own.

The .17 Remington

Chambered in one of the most popular bolt-action rifles ever made, the commercial version of this .17 cartridge has been with us in the Model 700 since 1971. In reality,

as an off-the-shelf rifle, the Model 700 as chambered for the .17 Remington is really hard to beat. Whether chambered in the .17 Remington or .375 H&H, the Model 700 gets its pedigree from a long line of famous and accurate ancestors. Starting with the Model 30 in 1921, the series started a progression of models to include the Model 720, 721, 722, 725, commencing with the improved Model 700 in 1962.

It’s not hard to see that Remington had its work to do in developing the .17 Remington for consumer use. After all, here you have a bullet that measures only .172 inch across its body diameter, a case tapped from the likes of the popular .223 Remington, combined with a bullet weight of only 25 grains (factory version) pushing in excess of 4,000 fps.

Rim size was also a major consideration especially for a new cartridge introduction. New tooling drives up the cost of development and gets the bean-counters nervous. Here, Remington took the .223 Remington case with a rim size of .378 inch – the same as the .222 Remington and .222 Remington Magnum – and handily adapted it to the present-day short action Model 700s. While many might criticize Remington for basing the .17 Remington on an overly large case, one has to look at the practical side of consumer marketing. Remington is not in the wildcat business (remember that nasty liability word) so with a case length of 1.796 inches and a rim size of .378 inch, they literally had a near instant, no sweat new product in which feeding problems were nonexistent.

The critics rose once more. They remarked, “Why go through all this trouble when you can take the .223 case and just neck it to .17 caliber?” Good question, but I think efficiency of the cartridge was the key. By using a smaller interior volume, the .17 Remington (with its shoulder moved back) can push a 25-grain bullet (on paper now) to about 3,960 fps with 21.0 grains of H-335. The unmodified .17-223 takes that same 21.0 grains to reach only 3,618 fps with 23.0 grains needed to even come close to 3,930 fps.

Dual purpose hunters who like to use the .22 calibers for “larger” small game also find the .17 Remington fascinating. For instance, looking at Table I helps illustrate some interesting comparisons.

Charts always tell the story, so there is not much to say except that if you love velocity and desire a pure varmint rig, the .17 Remington may be the cartridge of choice. Then too, since there is only one factory load at present in one bullet weight, handloading is the only way to go. (Remington currently offers two bullet weights. – Ed.) Cases are plentiful, ditto on the primers, and propellants like H-322, H-335, AA-2520, IMR-4320, W-760 and newer Varget seem to fill the bill handily. Bullets and bullet weights now range from 15 to 37 grains and are a full production item from the likes of Berger, Calhoon, Hammet, Remington and Hornady.

Actual reloading practices follow the norm in making up loads for the .17 Remington. First, it’s a good idea to fireform cases with a mid-range load and neck size only thereafter in the interest of accuracy. You’ll need a very small-necked funnel, and you’ll have to feed these cases slowly, especially with stick powders like IMR-4320. Patience must prevail, especially for those with larger fingers, as seating bullets will tax the best of us. I find it’s a good idea to chamfer the inside of sized cases to form a platform for these minute bullets to sit on as they are pressed into the cases during the seating and crimping operations. Other than that, standard loading practices prevail.

The .17 Mach IV

On the other side of the coin is the .17 Mach IV. Students of history are quick to point out that while the .17 Remington is considered the most popular .17-caliber cartridge, the .17 Mach IV beat it to market by about eight years.

Chatting with company honcho Dan Cooper, he advised that the company’s brand new Classic rifle was now ready in the Mach IV for my testing program. This company is on the forefront of supplying rifles to budding wildcatters, and if the .17 Mach IV doesn’t get your attention, how about one chambered in the .17 Ackley Hornet, .17 Squirrel, .218 Mashburn Bee, .22 K-Hornet or even the .22 Squirrel? Those are listed under the Model 38 Mini-Action; the Model 21 Short Action plays host to the likes of the .17 Javelina, .17 Mach IV, .221 Fireball, .223 Ackley and even the .22 and 6mm PPCs.

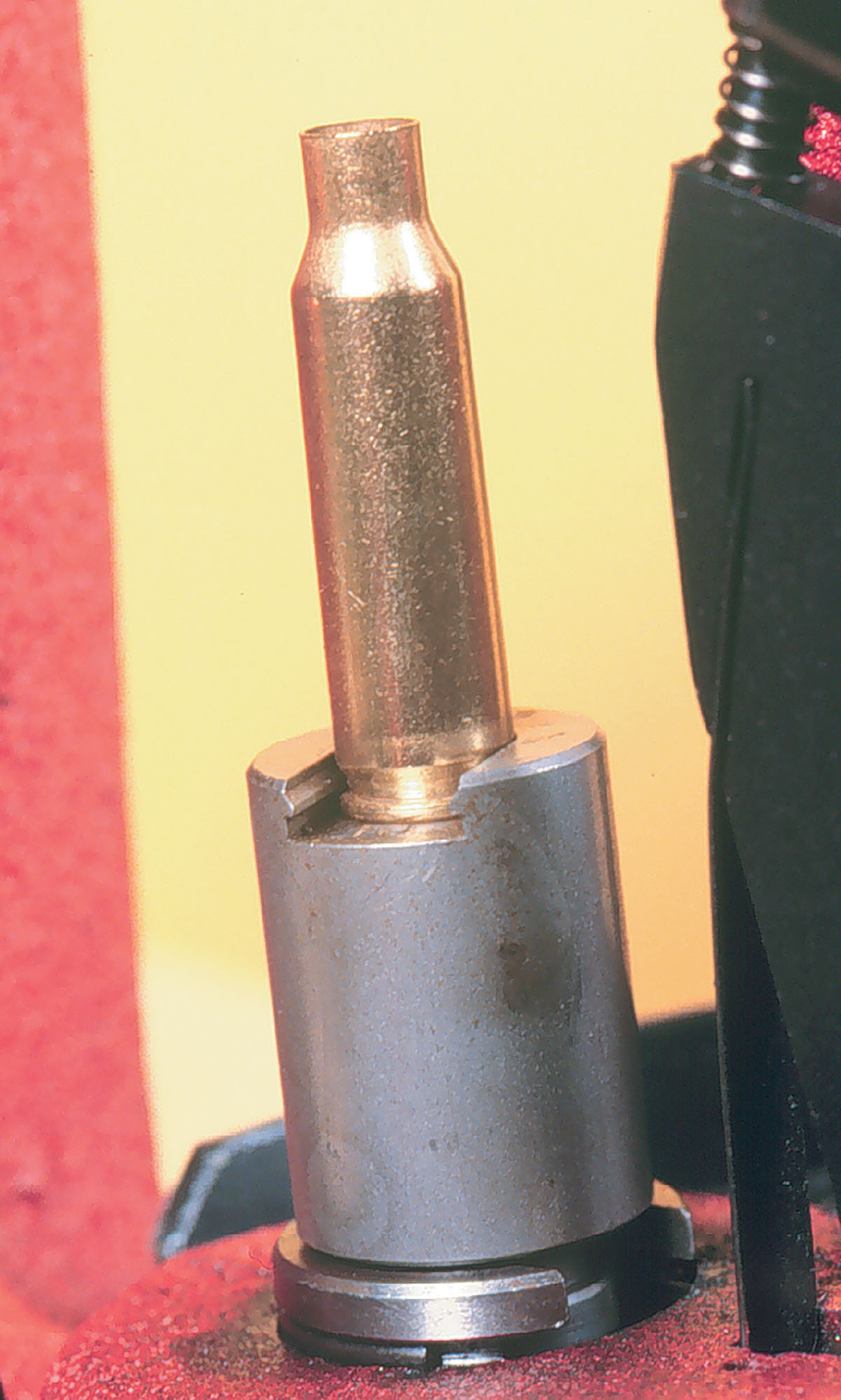

Cases for the .17 Mach IV are made from the .221 Remington Fireball and should be formed in two separate operations, and not by just running the case into a .17 Mach IV sizing die.

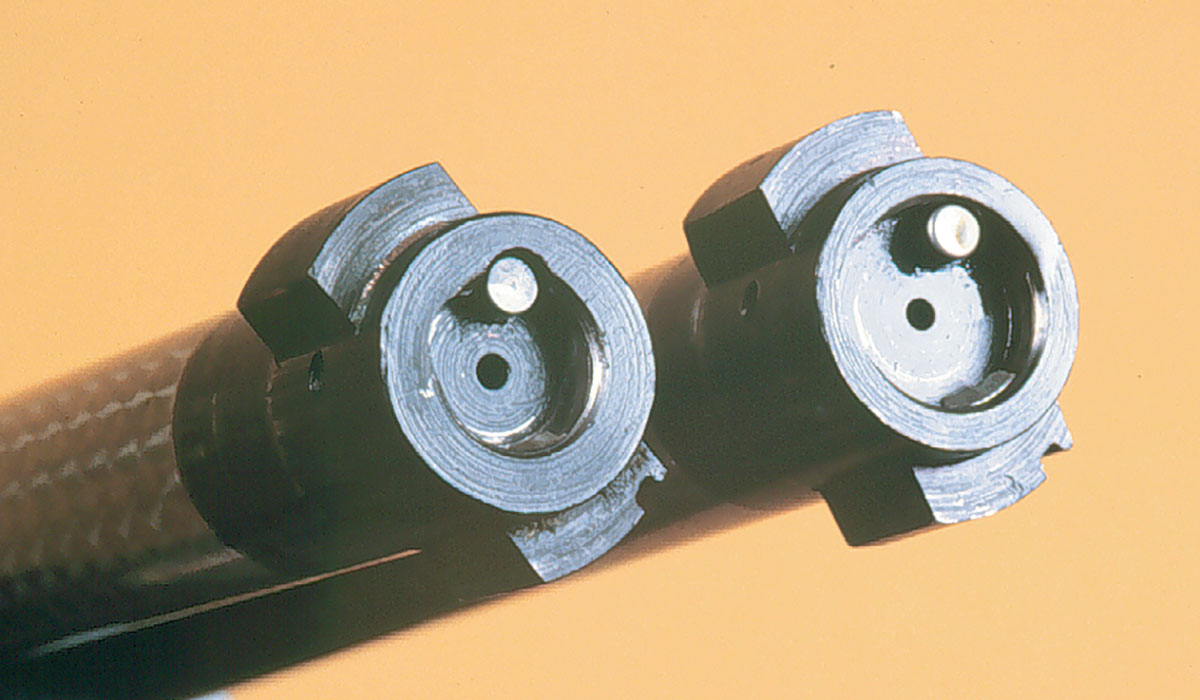

The first forming reduces outside neck diameter from .245 to .218 inch. From there the trim die now takes it from .218 to .205 inch. Finally, the RCBS full-length sizing die set will true up the cases, especially in the shoulder and neck area with a final outside dimension of .198 inch and a perfect inside diameter of .170 inch.

I like to fireform new brass using 18.5 grains of AA-2520 topped off with a Hornady or Remington 25-grain bullet and a Remington 61⁄2 primer. After the range session, a quick run through the die to just neck size all the cases makes everything ready for some serious ac-curacy testing. Velocity of this load in the Cooper rifle was 3,375 fps. Back home the die was set to allow the bolt to just close over a processed case ensuring the proper headspacing for optimum results downrange.

Loading either of these .17-caliber offerings requires perseverance and attention to all the details. Bullets are small, powder charges a bit touchy, and you should allow enough time to do the job right. Each powder charge should – read must – be weighed to ensure accuracy down to .10 grain. There are sufficient bullet choices, and I settled on the 19-grain Calhoon and 25-grain Remington and Hornady designs. For the 19-grain bullet, loading data for any 20-grain bullet can be used and can be found in Hornady’s new loading book. Calhoon recommends that you don’t push his bullet past 3,800 fps as accuracy and terminal results maybe impaired. If you need the additional velocity, the Hornady 20-grain bullet should satisfy any speed cravings.

In the larger .17 Remington, again IMR-4895 set the pace with a 1⁄4-inch group at 100 yards. Not a fluke, this load was repeated a few more times with the same result. Hodgdon’s H-322, IMR-4895 and W-760 would also get the nod for best of show. In the velocity column, AA-2520 hit 3,738 fps with the 19-grain Calhoon while H-335, IMR-4320 and W-760 wiggled past that magical 4,000-fps barrier with some very impressive readings for the Remington 25-grain bullet. Remington’s only factory load that incorporates the heavier 25-grain bullet pushed 3,800 fps with a very decent 3⁄4-inch group.

Finally, those concerned with trajectory need not fret with either .17-caliber cartridge. For instance, if both are zeroed at 300 yards, the Mach IV at 3,500 fps will rise only 5 inches above the line of sight at around 155 yards. The .17 Remington is better simply because of velocity; at 4,100 fps the midrange trajectory is about 3 inches.

For the wildcatter, the .17 Mach IV offers a challenge both in ammunition and finding a rifle. On the other hand, our old friend the .17 Remington is easy to load, has factory brass at your beck and call and used rifles are available.

.jpg)

.jpg)