22 Remington Jet

T/C rescues defunct handgun cartridge in rifles.

feature By: Stan Trzoniec | April, 13

This time around, we are dealing with the 22 Remington Jet, a cartridge that seemed destined for handgun use. When I discovered the Jet on the list, I called the custom shop to get the project going. Since I like the lighter frame of the Contender, versus the Encore, for summertime chuck hunting, I picked the tapered 24-inch barrel. Highly polished and detailed, this would be the perfect mate for a new .22-caliber reloading project while fitting in with other wildcats, including the 22 Mashburn Bee and the 22 K-Hornet. With a positive ejector at the chamber end, it carefully lifts the spent cartridge case so you can pluck it out of the barrel and reload it again without the hassle of it flying off into the pucker brush.

My Contender is the previous model, but the newer and improved G2 Contender sports the same receiver outline as the Encore, is easier to open, allows more room between the trigger guard and the stock and incorporates a newly designed automatic hammer block safety with an interlock. In any event, regardless if you pick up the early or newer Contender, barrel switching is the same. To finish off the gun for bench and field use, I mounted a Thompson/Center 3-9x scope with its proprietary rings and one-piece base set.

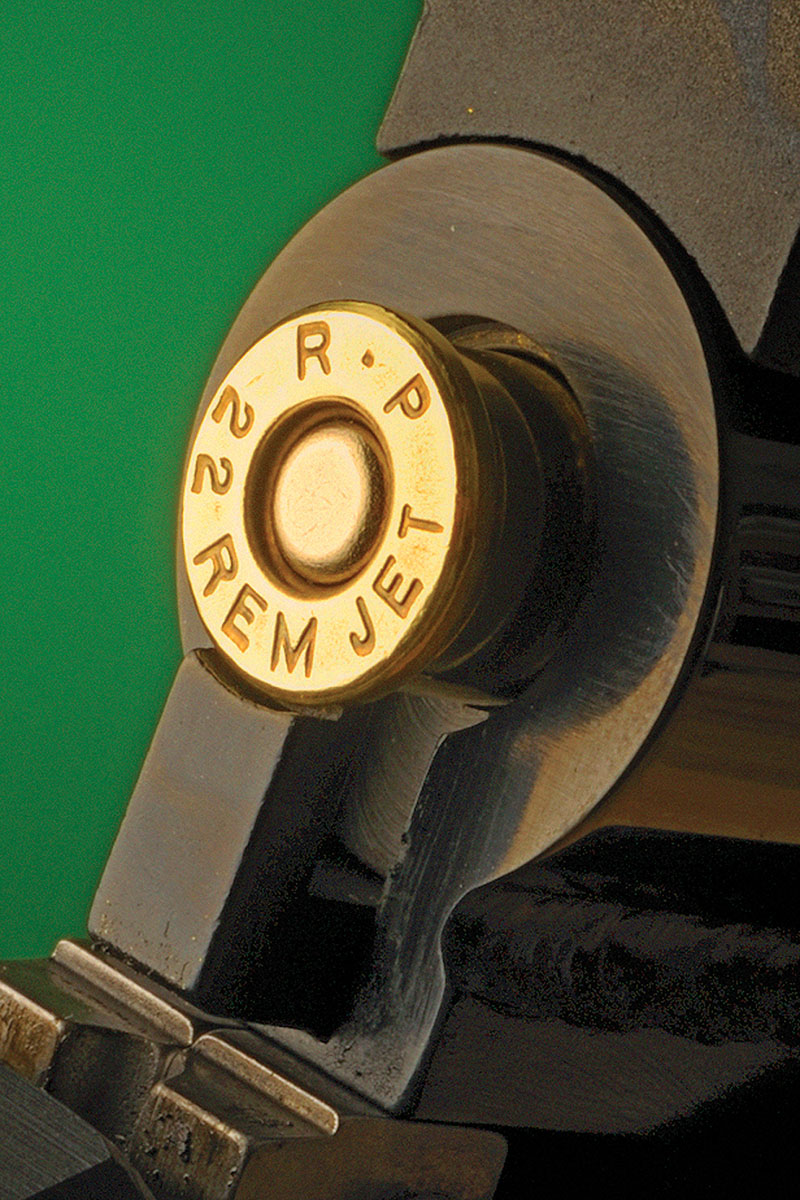

The 22 Remington Jet was developed by Remington and Smith & Wesson in 1961 to be used in the Model 53. Although it was popular at the time, enthusiasm waned after a short time, as shooters were having trouble with their new handguns. Apparently the tapered case of the Jet was backing out of the cylinder causing lockup problems, not to mention the frustration of having a new gun and being unable to shoot it correctly with factory ammunition. Today, it seems, the cartridge and gun have been retired with only a mention here and there around the collector’s roundtable, but not at my house.

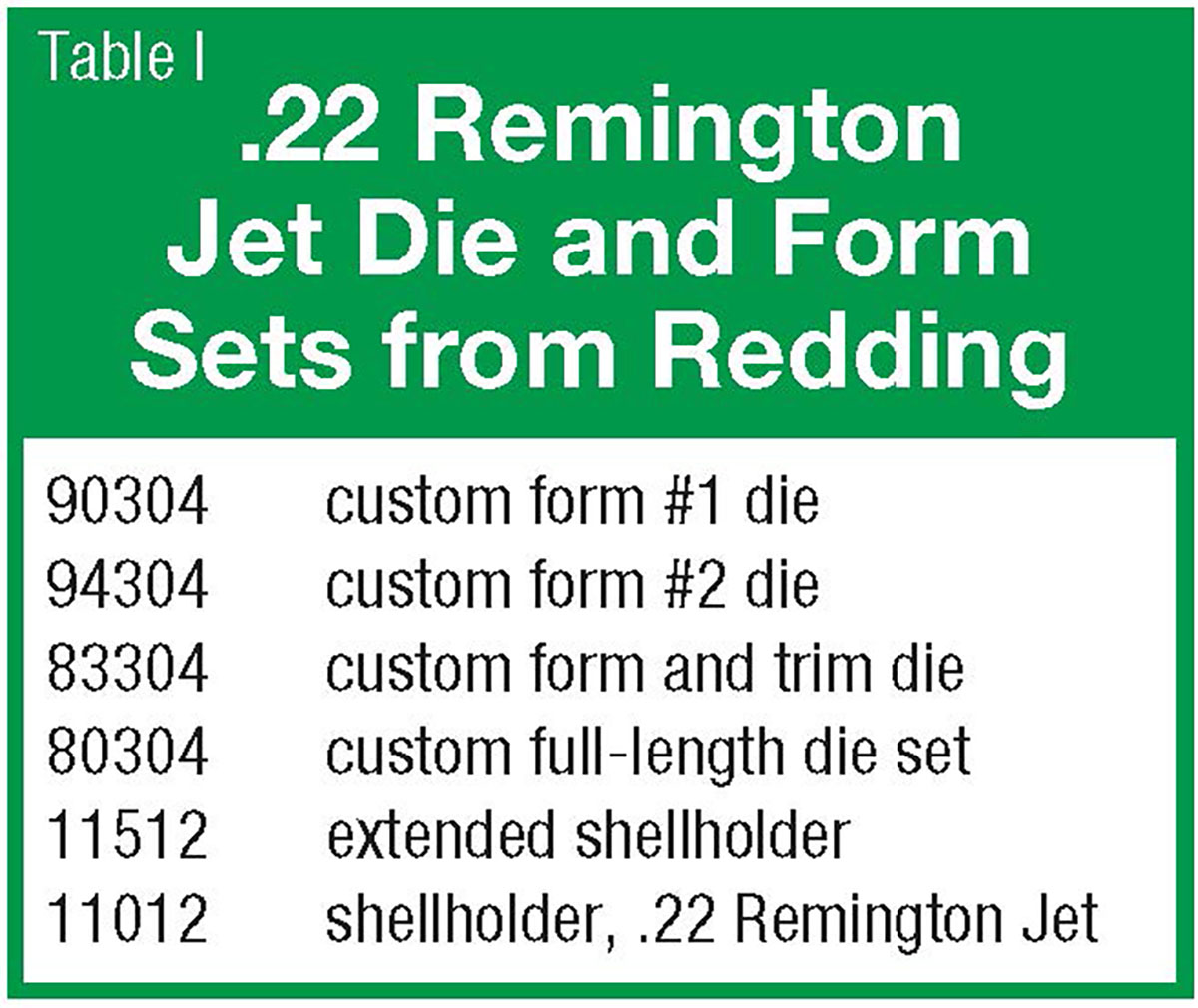

Next, the issue of brass comes up, and you can deal with this a number of ways. First, if you can find factory-loaded ammunition (good luck!), you can fire off the rounds to have brass fireformed to your chamber. Calling around to various collectors is an iffy situation, expensive at best, so I move on to the next alternative. I called the folks at Huntington Die Specialties (866-RELOADS), and they had 60 cases in stock, which were promptly sent. Even though 60 cases is a good start, I wanted more in my stash. The last solution is to make your own brass using a special die and form set. This was taken care of by Redding Reloading Equipment (1089 Starr Road, Cortland NY 13045) in short order, and to save you the grief of looking through endless pages of catalogs for custom die sets, Table I lists what you’ll need to turn out first quality 22 Remington Jet handloads.

The next thing on your list is at least four boxes of brand-new (not once-fired) 357 magnum brass from Remington or Winchester. Brass or nickel plated is okay; I found the forming process seemed to go easier with the traditional brass cases from start to finish. Stock up on small pistol magnum primers, my preference is CCI 550s, considering the size of the case and its capacity. Powders are next, but I will get to that in a minute.

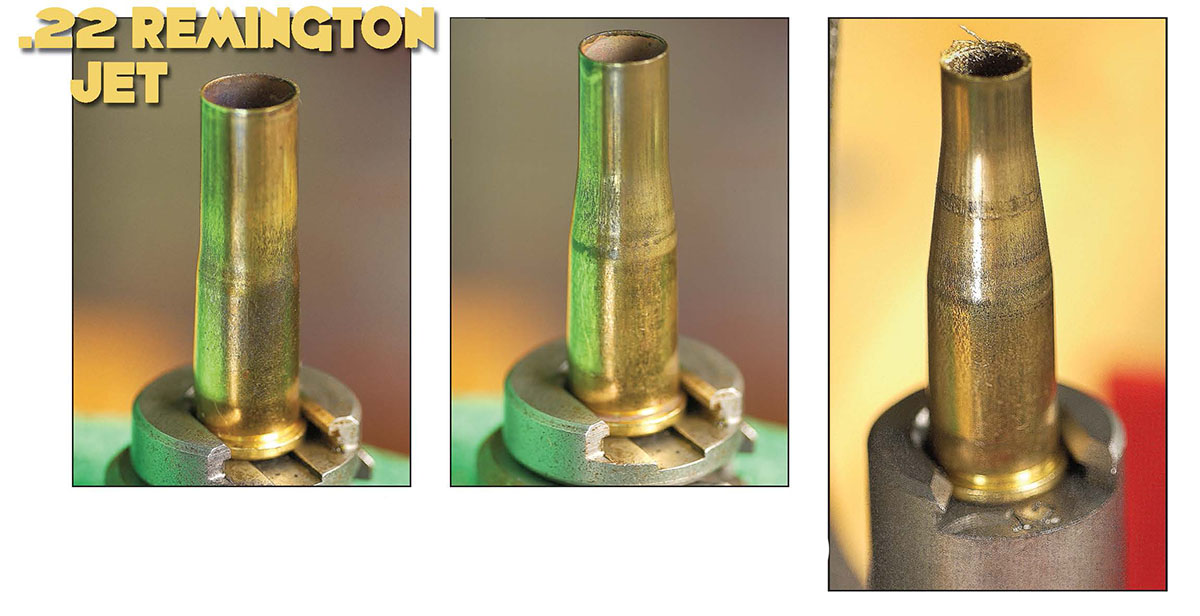

From the onset, trying to form 22 Remington Jet cases from 357 magnum brass without the annealing step is a lost cause in both time and materials. The cases will not take the sharp angles needed to produce this brass, and split or crushed necks will cause a 100 percent fatality rate. Annealing is easy, quick and consists of nothing more than placing a case in about .25 inch of water, heating the neck area almost to the point of redness, then pushing them over in the water to quench and cool them. I use an old bread pan and a Micro or hobby torch that runs on Ronson butane fuel.

Once you get a rhythm going, most folks will be surprised how fast the process goes, and you will have a pile of cases ready to go in short order. After they are fully dry, set up the Redding form #1 die, lube the cases and start pushing them up and into this die. This first die will reduce the neck from .375 (new case) down to .336 inch on the first pass. Run the whole batch through this die before moving on.

Next, move on to form #2 die and run all the cases through it. Here the neck will be reduced to .298 inch in preparation for the next file and trim die, which reduces the neck to .255 inch with an inside diameter of .230 inch. In order to push the case up and into this last die for trimming, you will need to install the extended shellholder as shown in the photographs.

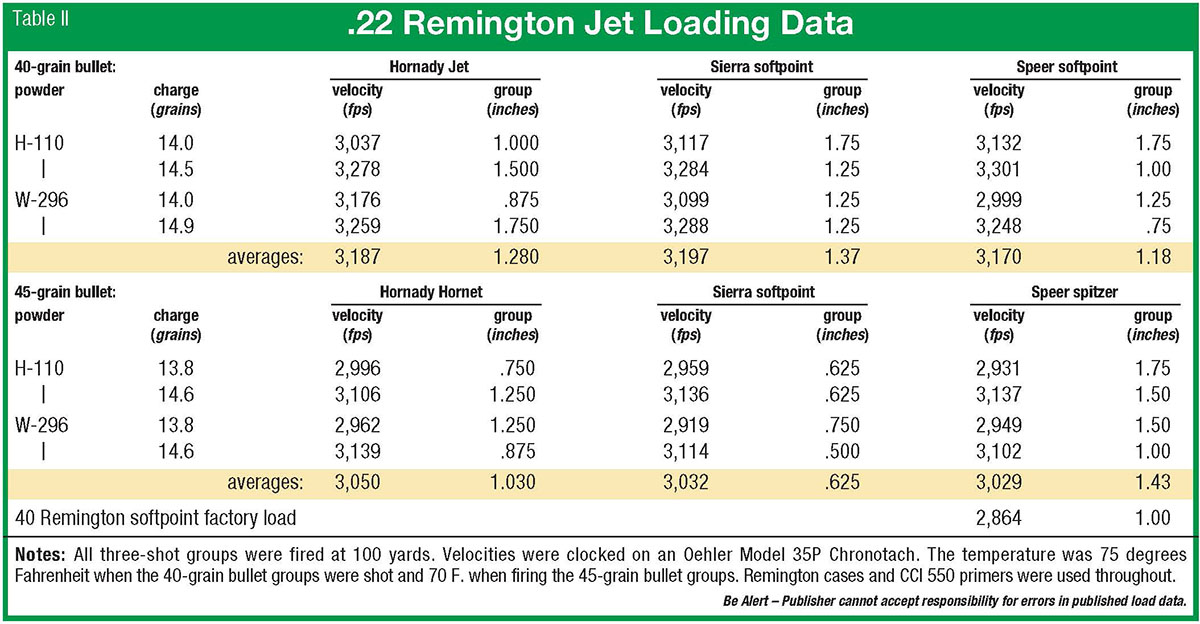

The 22 Remington Jet holds 18.9 grains of water, which puts it in the same range as the 218 Bee. Since there are no references made on using the 22 Jet in a rifle, I turned to Wayne Blackwell’s (9826 Sagedale Dr., Houston TX 77089) “Load from a Disk” program. Putting in all the parameters, such as barrel length, overall length of the bullet and the bullet used, the program came up with using 2400, Lil’Gun, H-110, W-296 and a few others I did not have in stock.

Considering past experiences, I choose to go with H-110 and W-296 for velocity readings and the ease of powder flow through the measure. Looking up 2400 with the 45-grain bullet, for example, I was limited to only 14.0 grains of propellant, which gave 3,009 fps. Moving up to 14.9 grains with 2400 gave 3,202 fps but with pressure readings in excess of 50,500 CUP. Compared to using, say, 14.6 grains of H-110, velocities would be in the neighborhood of 3,147 fps and 48,161 CUP. Considering the smaller case volume of the Jet, I decided to stay with H-110 and W-296 for at least the first go around.

With the cases ready, priming, loading and bullet seating were uneventful. I seated the 40-grain bullets to an overall loaded length of 1.550 inches and the 45-grain bullets at 1.650 inches. Since this is a single-shot rifle, you have the option to crimp if you like, but just to keep everything on an even keel, I applied a light crimp on all rounds.

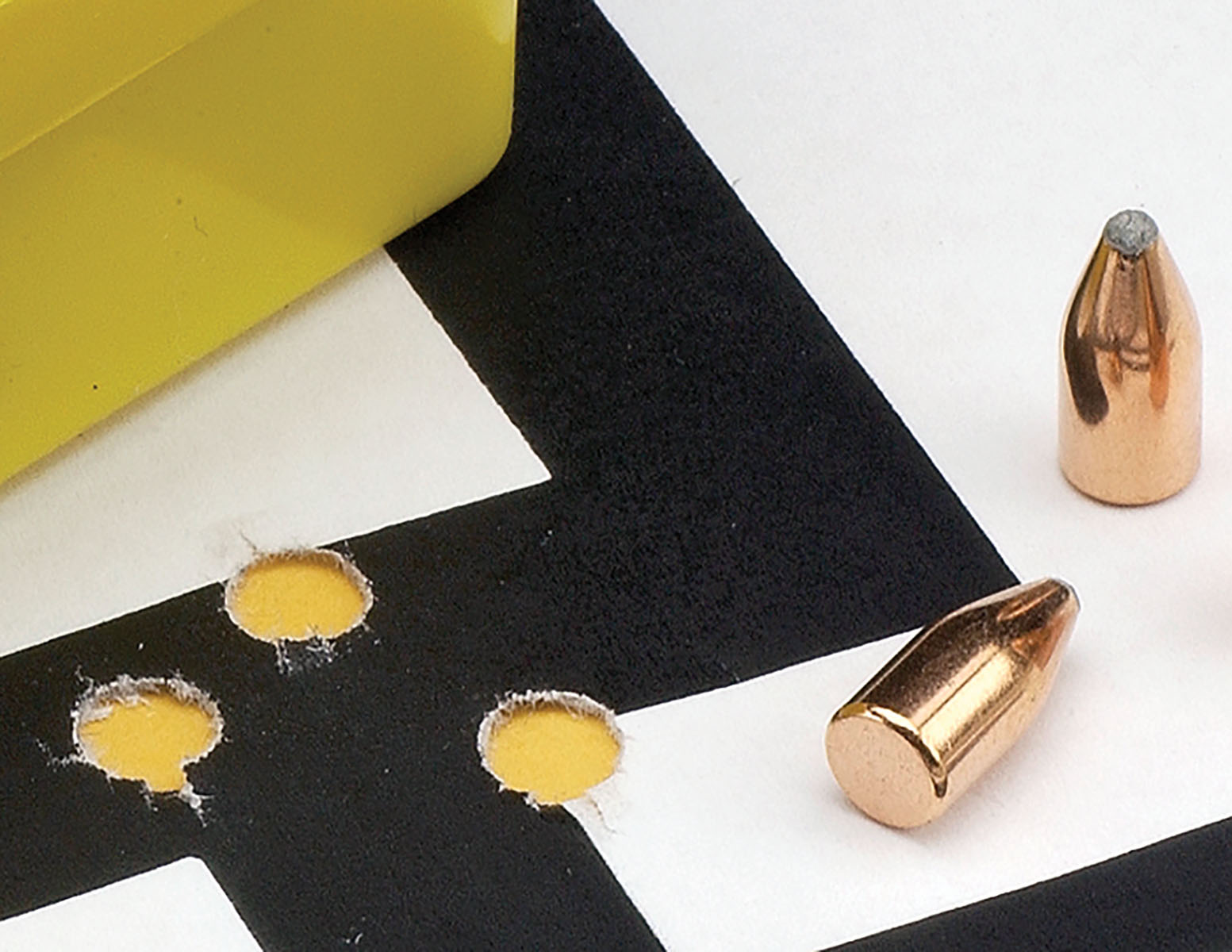

Counting the factory loading, I fired 25 groups in two different days with a temperature spread of only five degrees. Testing went smoothly, and the results were very encouraging, considering this round was made specifically for a handgun. To my surprise, some of the 100-yard, three-shot groups went into .5 inch.

When it came to the results of the 40-grain bullets, group size was pretty much spread between H-110 and W-296. If I had to pick the pet of the day, it would be the Speer softpoint with 14.9 grains of W-296 for almost 3,250 fps. Using the heavier bullet would be my choice for midsummer woodchucks at closer range than say the 223 or 22-250 Remingtons, and by closer, I’m talking roughly 100 yards. Pick of the day is the Sierra softpoint with 14.6 grains of W-296 for 3,114 fps. Looking at drop tables, this is a good load to zero at 100 yards; bullet drop at 200 is only 3.6 inches. Placing the crosshairs just below neck level will deliver the bullet on any part of the body. As a footnote, the Sierra softpoint was the top performer in all categories and all powders with the heavier bullet with an average of .625 (5⁄8) inch.

When I first started this project, one of my varmint shooting friends said it couldn’t be done. “The case is too small, the bullets are too light, and there isn’t enough powder to get decent velocities.” And besides, he went on, “It’s only a pistol cartridge.” That’s a quote, but now that he’s seen the results, he might have to eat some of his words.