E.R. Shaw 22-250 Ackley Improved

Swift Performance in a Wildcat

feature By: Stan Trzoniec | April, 13

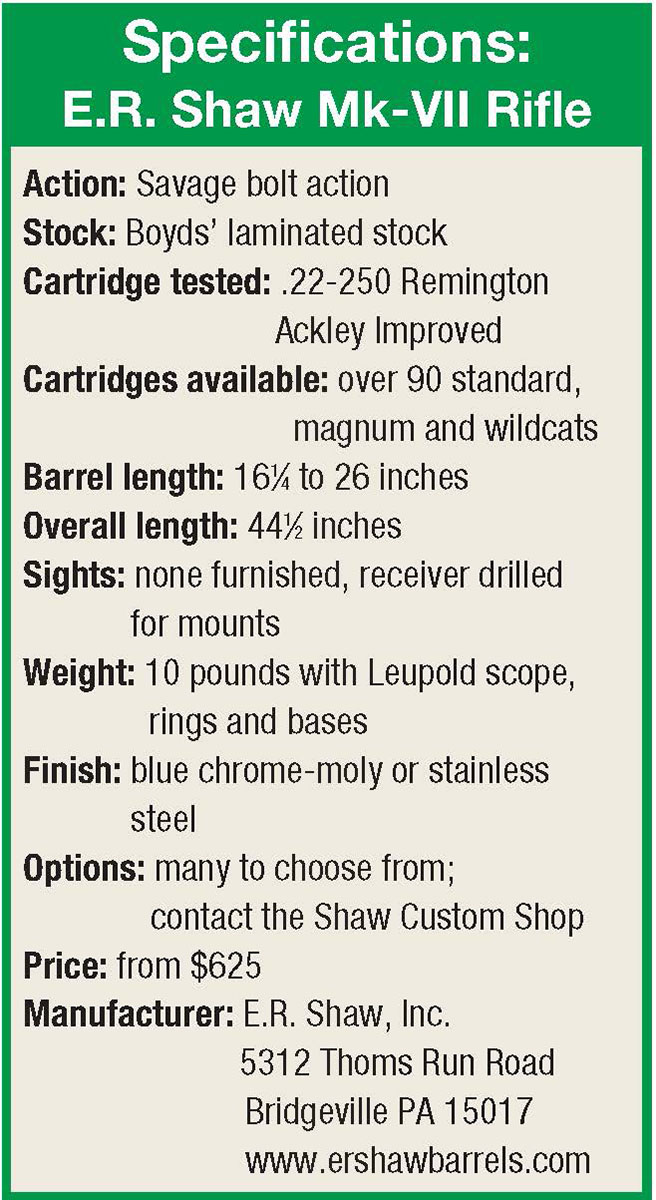

As word got around, Small Arms Mfg. was turning out as many as 2,500 barrels a month to be installed on surplus Enfield, Springfield and Mauser actions. The E.R. Shaw division was started to supply these barrels through a mail-order operation with the bulk of the commercial sales going out the door under Small Arms Mfg. Today, with investments of over $1.5 million, brand-new CNC equipment helps with the production of both chrome-moly and 416 stainless steel barrels, so the next stage was the introduction of a Shaw rifle to combine the resources of both companies in a production-custom grade firearm.

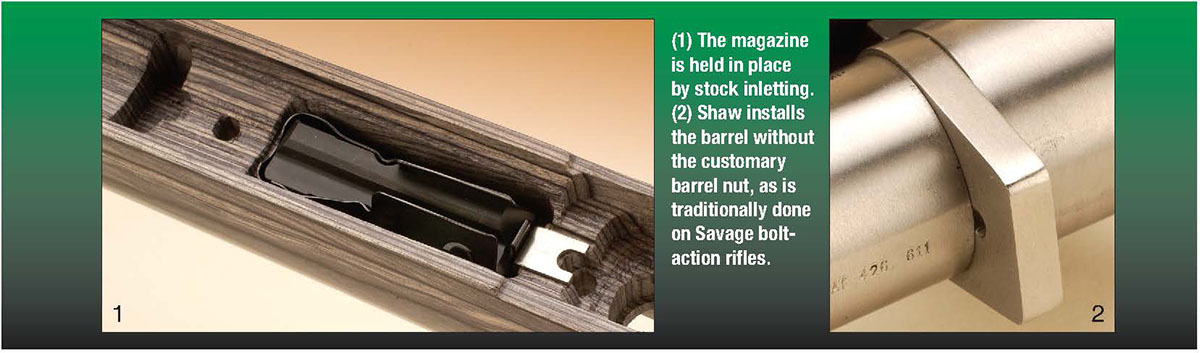

Since the Savage action has been covered in detail many times in Rifle and Handloader, I’ll just skim over the basics and how it fits into the Shaw concept of its company rifle. For one thing, rather than experience the expensive tooling costs that are generated by starting from scratch with a new rifle and receiver, through a licensing agreement with Savage Arms, E.R. Shaw has combined one of the most popular actions in the shooting sports with that of its finely honed barrels. There are details, however, that separate both companies and their final products.

One, the Shaw Mk-VII bolt is polished brightly, without jewelling or logos of any kind. The same dual locking lug design is still there to include both a front and rear set of lugs. The front set locks the bolt into the breech, while the rear set acts as a gas baffle to protect the shooter in the unlikely event of a case rupture. The extractor and a plunger ejector are located in the bolt face, and the rear of the bolt has a second gas baffle, followed by a checkered bolt knob, although the bolt handle on the Shaw rifle has less of a downward turn than on the Savage.

As primarily a varminter, I ordered a 24-inch barrel that tapers to .720 inch at the target-crowned muzzle. Made in stainless to match the receiver and related parts, I asked that they make the barrel with their special patented spiral fluting. I like this feature, and during the tests the barrel did maintain a constant temperature, while allowing three to four minutes between three-shot groups.

Shaw completes the rifle with a laminated stock from Boyds’ Gunstock Industries. Laminated in a gray, black and brown combination, it is profiled in the JRS Classic pattern complete with a cheekpiece and rubber buttpad. There is no exterior magazine release or floorplate, which adds to the streamlined appearance of the rifle. To keep the rifle in a worklike appearance, the stock is coated with Boyds’ own satin finish that is virtually waterproof and durable for the rigors of outdoor use.

For the serious woodchuck season starting to unfold this year, I installed a Leupold VX-III 4.5-14x 40mm. The body on this scope is 30mm and includes a side focus-parallax adjustment that takes the place of the usual front ring to dial in distance and clarity. Installed on this scope is the Leupold Varmint Hunter’s reticle that includes aiming points to stretch shooting distance by way of horizontal bars (up to 500 yards) and windage adjustments by dots on either side as to compensate for wind in increments of 10, 20 or 30 mph.

To add to the practical use of the scope in the summer sun, I added both a 2.5- and 4-inch lens hood, end caps and a yellow Leupold Alumina filter for hot, humid and sometimes overcast days. Sandwiched between the lens hoods, the added contrast is very pronounced on these tropical-like afternoons. Total weight of this rig with the scope, rings and bases but not loaded with ammunition is 10 pounds.

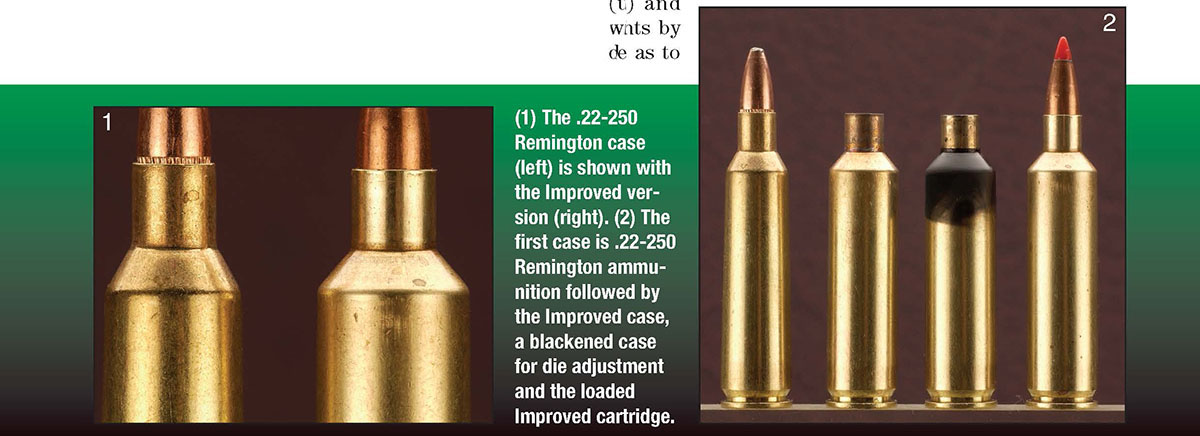

Being chambered for the 22-250 Remington Ackley Improved was a treat. I’ve always liked this round, and now thanks to Shaw it became a reality. If one wants to get into wildcatting with a minimum of effort, this is one of the best. An interesting feature of the improved versions is that one of the requirements is they must fit and fire in the improved chamber with factory ammunition of the same type. Thus, with this wildcat, case forming is easy and painless. All one has to do is load common 22-250 Remington ammunition into the improved chamber and have at it.

The other requirement is that they have a shoulder angle of 40 degrees, which adds to the controllability of brass flow, eliminates body taper and shortens the case during the fireforming process. With standard handloading practices, you can expect to add about 10 percent more powder, and this is evident with both the factory and wildcat 22-250.

To get the barrel in good shape and to remove any rough edges in the rifling, I took the rifle out three times before turning serious with loading. I fired off three to five rounds, let the barrel cool and when I had 100 rounds of Improved brass, I started loading.

Regardless of how you look at it, neck sizing helps reduce stress on the brass, when compared to full-length sizing. One other point worth noting is that when fireforming cases for the Improved version, I would use factory fresh brass. So far, I’ve had no trouble with neck splitting, shoulder problems or case separation.

At the bench, my usual practice of smoking an unfired case with the flame of a candle helps to check egress of the case in the neck sizer. If you don’t want to go through this step, I found that when the Redding neck sizer is installed and turned down to just touch the shellholder, you are pretty close to the case shoulder. As it was, the Redding set was perfect in every respect, and upon reinstalling a dummy case (just a bullet – no primer or powder), operation was smooth and without problems.

A touch of lube between the thumb and forefinger places enough lubrication on the neck to keep it from collapsing the shoulder. To keep the neck expanding operation smooth, you can place a very small amount of lube on a Q-tip® and swab the inside of every other neck in the cartridge tray.

From here all primer pockets were cleaned, the mouth was deburred both inside and out, and the entire batch of neck-sized cases went into a bucket of Iosso case cleaner to renew the factory-fresh appearance. With the cases void of lube, a close inspection is a good idea to check for splits or other irregularities before moving on. The overall length was measured, and true to form for an Improved case, this measurement actually was shorter than when it first went into the chamber.

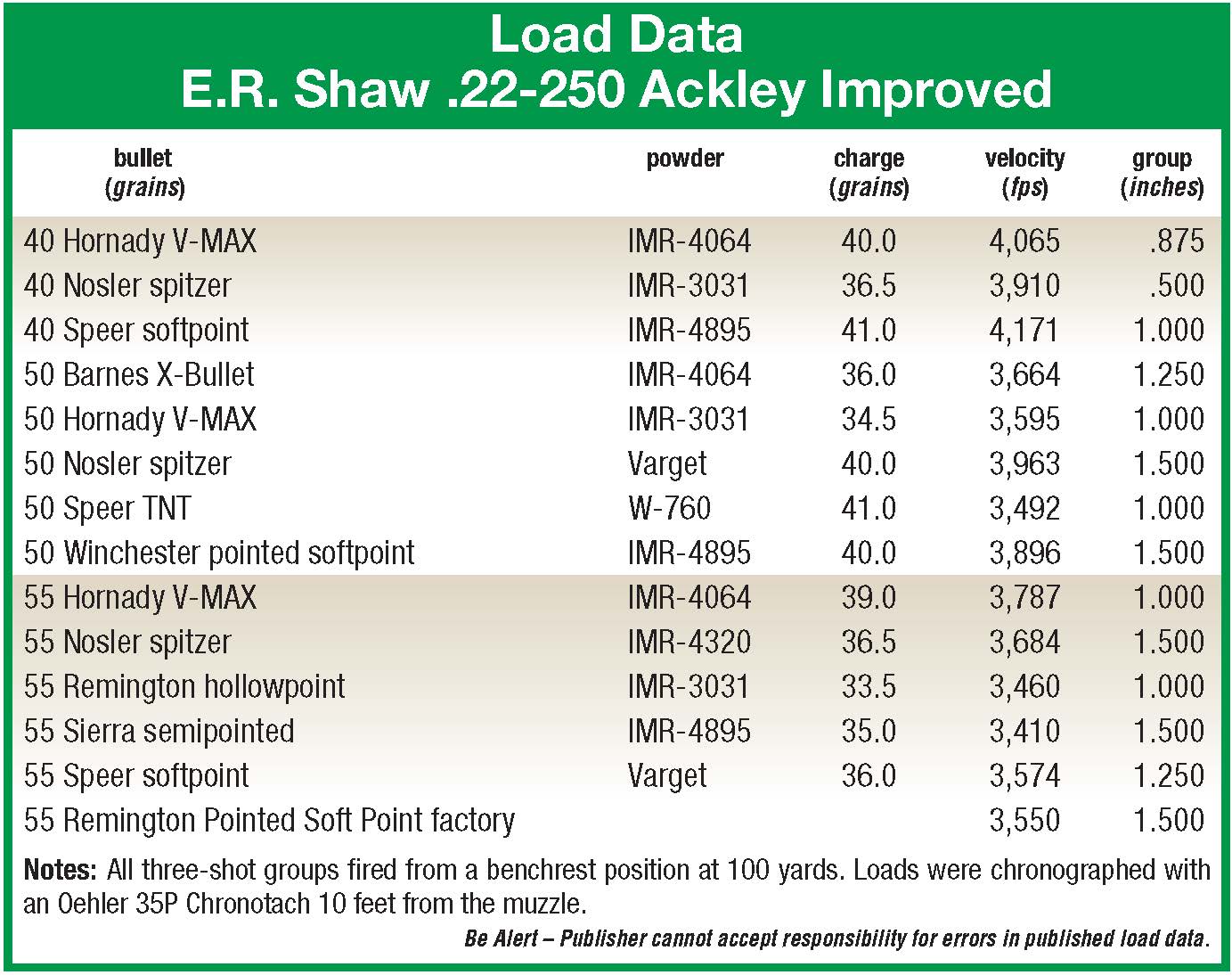

Priming was done with Remington 9 1⁄2 Large Rifle primers, and medium-burning powders were used in the 22-250 Improved. Research consisted of loads in the Nosler Reloading Guide 6 with additional data from P.O. Ackley’s book Handbook for Shooters and Reloaders, Volume I and Wolfe Publishing’s book Wildcat Cartridges. While the Improved version can use bullets up to 70 grains, my preference is for lighter-weight bullets from 40 to 55 grains.

Even with the Improved version, there is nothing difficult or, for that matter, anything exotic to purchase in the way of powders. My choice went to propellants like the IMR brands of 4064, 3031, 4895, 4320, Hodgdon Varget and Winchester W-760.

Some may compare the 22-250 Improved to the Swift, which is understandable. However, the Improved version will use, on average, about one grain more powder than the Swift to obtain similar velocities. It’s your choice.

Because of the texture of these coarse-grained powders, I would drop the charge as close to the charge weight I was looking for, then trickle up to the total amount. In all cases, I made sure I hit the precise charge weight on my list to help maintain accuracy and velocity as close as possible. All the cartridges had an overall loaded length of 2.350 inches, except for the 40-grain Speer softpoint and the 55-grain Remington hollowpoint loads, which were seated to 2.300 inches because of their shape and bullet length.

When the day came for testing, it was perfect for shooting .22-caliber bullets. The wind was at absolute zero velocity, temperatures were in the mid-40s with high overcast. I set up a Caldwell BR front rifle rest with an older and much used Cole’s sandbag on the rear and began in earnest. During the testing period, I would wait three to four minutes between groups. The barrel remained at a constant temperature, which was determined by touching it.

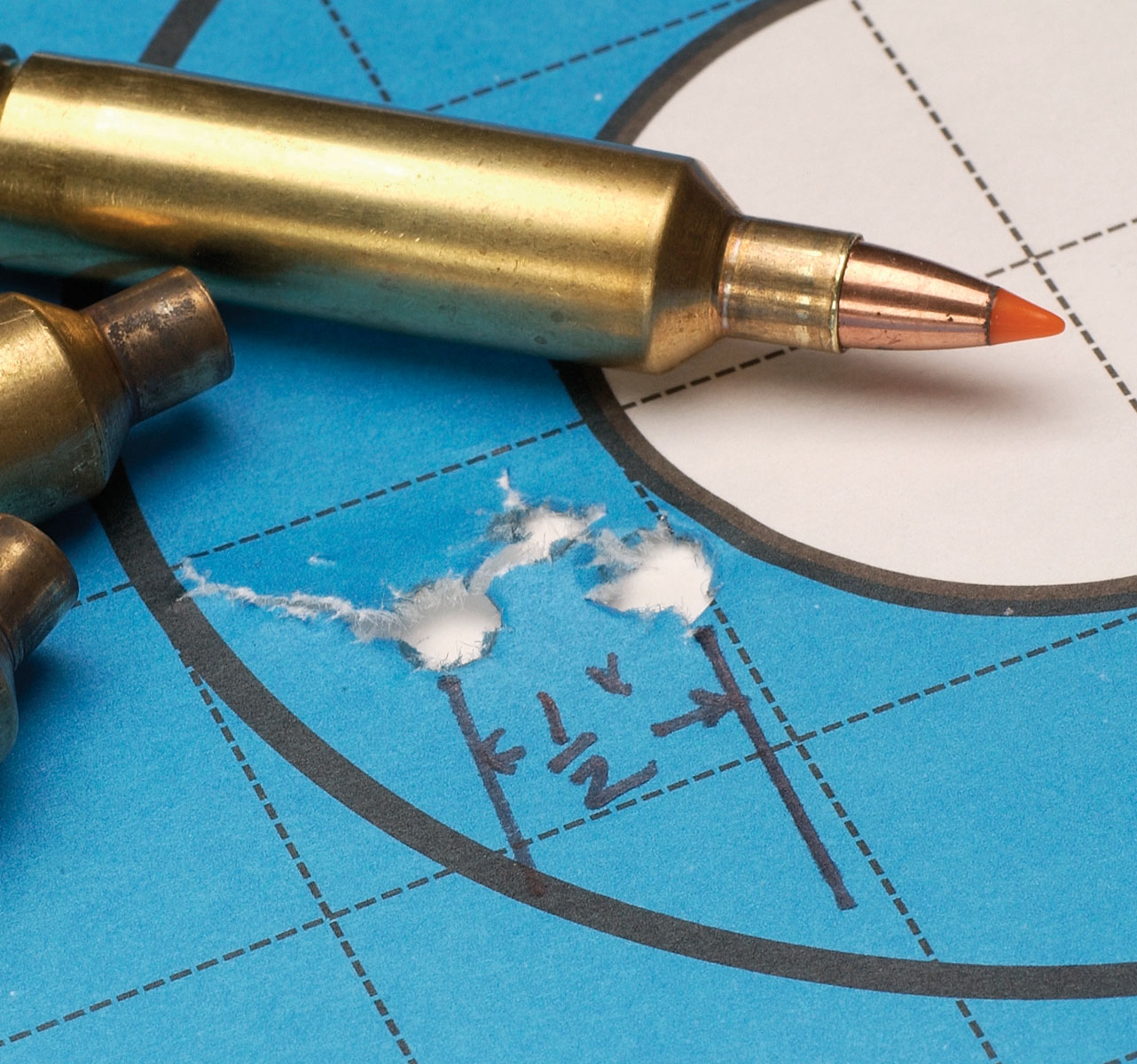

Looking at the results, the best groups were shot by the lighter 40-grain bullets from Hornady, Nosler and Speer with the Nosler brand hitting .5 minute of angle (MOA) at 100 yards with IMR-3031. While it did not hit the highest velocity readings, nevertheless at 3,910 fps, I can live with that. If you are looking for velocities of 4,000+, the Hornady V-MAX came in with 4,065 fps with groups under an inch. The best velocity of the day with 40-grain bullets was the Speer softpoint and one-MOA groups at 4,171 fps.

With 50-grain bullets groups started to widen but never went over the 1 1⁄2-inch mark. For some reason, when I’d get two holes so close to one another that you would swear they were touching, the third shot would open the group. The potential for the rifle is obviously there, and this time I could not blame it on the wind or weather. One-inch groups came from the Hornady V-MAX (which I used on a chuck hunt) and the Speer TNT with the highest velocity going to the Nosler brand sparked by 40.0 grains of Varget at 3,963 fps.

The heaviest group of bullets used included a sampling from most of the major bullet manufacturers and again, except for the one-inch group from the Remington hollowpoints (with IMR-3031), the rest fell into place around 1.25 to 1.5 inches downrange. In this set of bullet samples, the Hornady V-MAX led the pack with both the highest velocity (3,801 fps) and the smallest group (one inch).

So, how do we see the bottom line after all this fussin’, shootin’ and loadin’? On the one side, this rifle is put together like a truck and will hold up for years to come. On the other hand, while accuracy is good for general hunting duties, I want to spend more time at the bench to fine tune it even more with the heavier bullet weights. In my part of the country where most older hedgerows don’t max out to more than 100 to 150 yards, the wily woodchuck, fox or coyote will not know the difference, but out West, the groundhogs will be laughing back at you unless you can come up with consistent accuracy of well under an inch. Still, if you look at the overall picture and average all the groups (with the exception of the factory sample), the rifle did well at a mean of 1.14 inches for the day’s shooting.

E.R. Shaw has taken all the cutting-edge technology available to produce a rifle to meet consumer demand on a custom basis but with a production price. As company president Carl Behling said, “It was the next logical step.” Indeed, it was.