.17 Remington Fireball

Mach IV Is a Factory Standard!

feature By: John Haviland | August, 12

Seventeen-caliber centerfire cartridges have been neglected so long that to find even the slightest enthusiasm for them you have to go way back to 1971, when Remington introduced its .17 Remington. But that might well change with Remington’s new .17-caliber cartridge called the .17 Fireball, which is actually an old .17-caliber cartridge.

History of the .17s

Utah gunsmith and experimenter P.O. Ackley did more to promote .17-caliber cartridges than anyone. The first .17-caliber cartridge he made was the .17 Pee Wee in 1945, which was based on a necked-down .30 Carbine case. Subsequent .17-caliber cartridges Ackley developed included the .17 Hornet (necked-down .22 Hornet), .17 Bee (necked-down .218 Bee) and in 1955 the .17-222 Remington. Other .17 wildcats were based on the .222 Magnum, .223 and .22-250 Remington cases and the .225 Winchester. Remington capped off all this in 1971 when it set the shoulder back on a .223 case, necked it to .17 caliber and introduced the cartridge as the .17 Remington.

The O’Brien Rifle Company developed the .17 that interests us here. This cartridge was made soon after the .221 Remington Fireball was introduced in 1962 and is the .221 case necked down to .17 caliber and called the .17 Mach IV.

Back in the mid-1970s, coyote hides were worth upwards of $90 apiece, and a few coyote hunters I knew bought .17 Remingtons because the 25-grain bullets made a pinhole going in and fragmented inside the coyotes. That saved a major sewing job, common with bullets fired from the .22-250 Remington that tore a big hole when they exited. But the .17 Remington never really caught on. And for the last 37 years, this speedy .17 has stood on the sidelines, although Remington chambered the cartridge in its Model 700 Light Varmint rifle for a time.

So how come the .17 Remington gathered such little interest? Although there were glowing reports of .17s killing big game, hunters found its light bullets were more suited to game not larger than coyotes, and out past 300 yards its bullets had shed most of their energy. Out there the light bullets also supposedly wafted in the wind like a feather. One criticism of the cartridge that haunts it to this day is that it fouled its tiny bore so badly that after as few as 10 shots accuracy went to pot, and 100 rounds might permanently ruin the bore.

But out of the blue in 2007, Remington essentially took the O’Brien Rifle Company’s .17 Mach IV cartridge and introduced it as its .17 Fireball. Eddie Stevenson of Remington said one reason for the introduction of the .17 Fireball was to capture some of the buzz from the extremely popular .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire.

Remington currently loads the .17 Fireball with a 20-grain AccuTip-V bullet with a stated muzzle velocity of 4,000 fps. Remington also plans on coming out with loads using a

25-grain bullet that’s less expensive than the AccuTip-V.

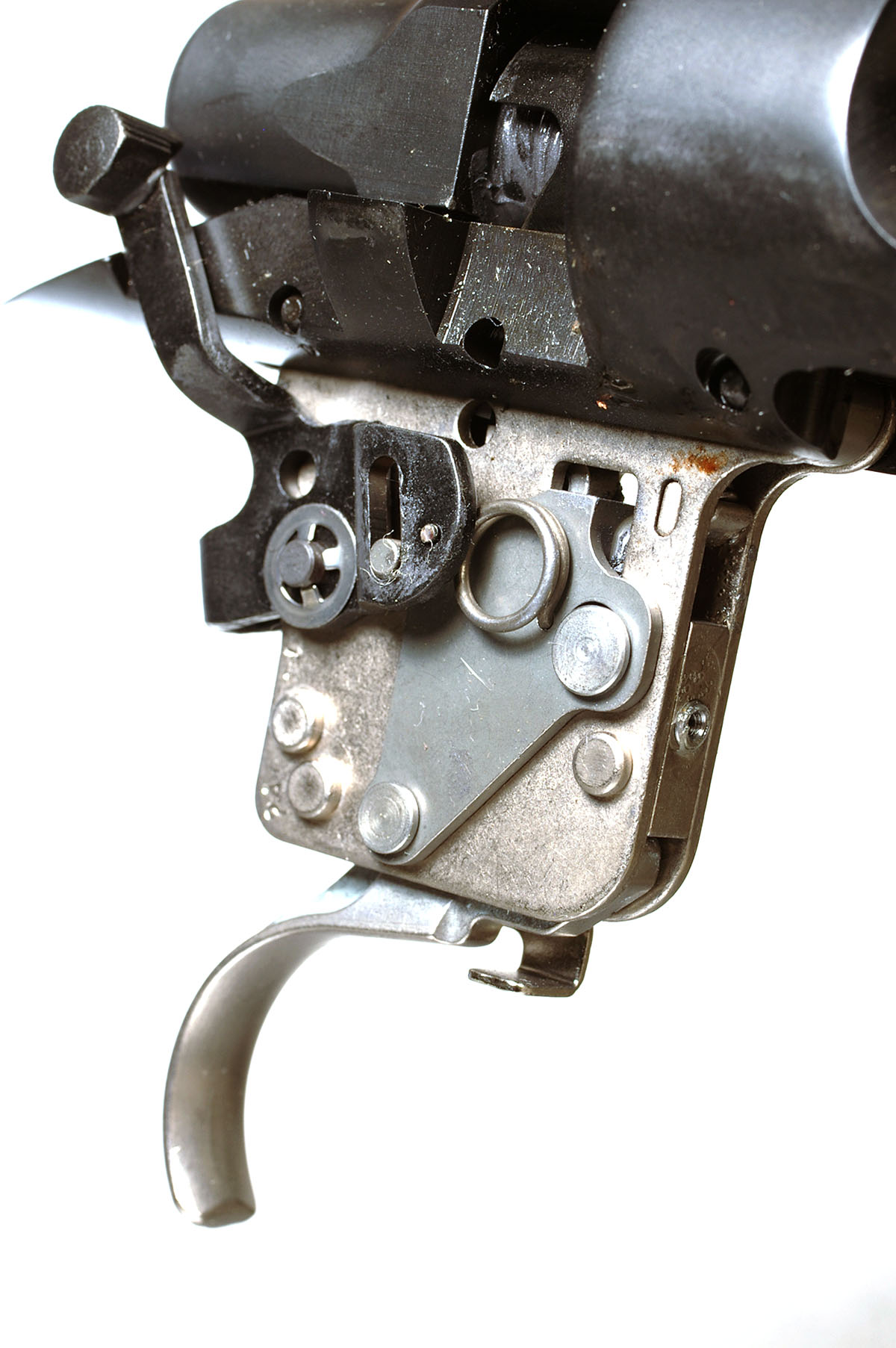

Remington went all out for the little cartridge and chambered it in its Model Seven CDL (20-inch barrel, 61⁄2 pounds), Model 700 Varmint Synthetic Fluted (26-inch barrel, 81⁄2 pounds), Model 700 SPS Varmint (26-inch barrel, 81⁄2 pounds), Model 700 SPS (24-inch barrel, 71⁄4 pounds) and Model 700 CDL SF (24-inch barrel, 73⁄8 pounds).

The Fireball in the Field

One spring I spent two days shooting prairie dogs on the Wyoming plains with a Remington Model Seven CDL and Model 700 SPS Varmint .17 Fireball and a Model 700 VL SS with a thumbhole stock in .22-250 Remington.

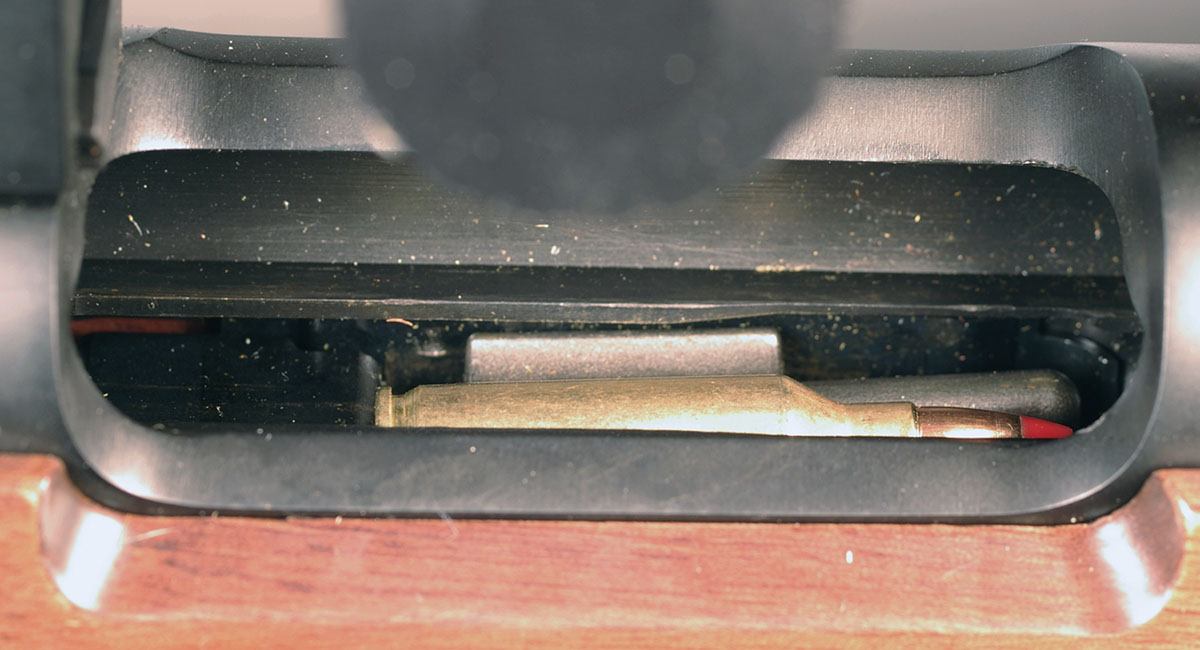

The criticism of .17-caliber cartridges fouling bores made me wonder how badly the Fireball gummed up a barrel, so I conducted a little experiment. My prairie dog shooting partner and I fired 300 Remington factory .17 Fireball rounds through the Model Seven the first morning of the shoot. With the light contour barrel still hot enough to brand cattle, I fired five shots on a target at 100 yards. Four of the bullets landed in .75 inch, with the fifth out another .5 inch. Even after the Model Seven had been fired 500 times, it took only five solvent-soaked patches to clean its bore. So the bore fouling issue should not be a concern with the .17 Fireball.

Excessive wind drift is another problem that has weighed down the reputation of lightweight .17-caliber bullets. While shooting prairie dogs at 250 yards and farther, I did have to aim into the wind a bit, even if the tops of the grass barely swayed. Shooting a .22-250 Remington with 55-grain bullets, at the same ranges and with the same amount of wind, a hold on the upwind edge of the dog resulted in a hit.

According to a ballistic software program, Remington’s .17 Fireball 20-grain AccuTip-V with a muzzle velocity of 4,000 fps is blown off course by a 15 mph wind about 7.5 inches at 200 yards, 17.8 inches at 300 yards and 35 inches at 400 yards. In comparison, a .22-250 Remington shooting a 55-grain bullet at 3,680 fps drifts 2.26 inches less at 200, 5.7 inches less at 300 and 10.8 inches less at 400 yards.

My partner and I used the Fireball mostly to shoot prairie dogs between 100 and 250 yards. At those ranges the little 20-grain pills carried enough oomph to quickly knock them off. We also shot a few at 500 yards and slightly farther. Way out there the tiny 20-grain bullets just poked a hole through the varmints. At 500 yards the .22-250 Remington made spectacular hits. So let’s call the .17 Fireball an honest 300-yard cartridge.

Recoil is where the .17 Fireball and the .22-250 Remington part ways. The .22-250’s kick certainly isn’t hard on the shoulder, but it’s enough to knock back a 10-pound rifle so the sight picture is lost. But the recoilof the .17 is so gentle that even the fairly light Remington Model Seven rifle barely moves on recoil. In fact, the scope crosshairs barely jump off the target. That’s especially enjoyable for the fun of seeing your hits or knowing how much you missed and adjust for the next shot. That light recoil and flat trajectory make the Fireball fun to shoot, and shoot again and again.

Handloading

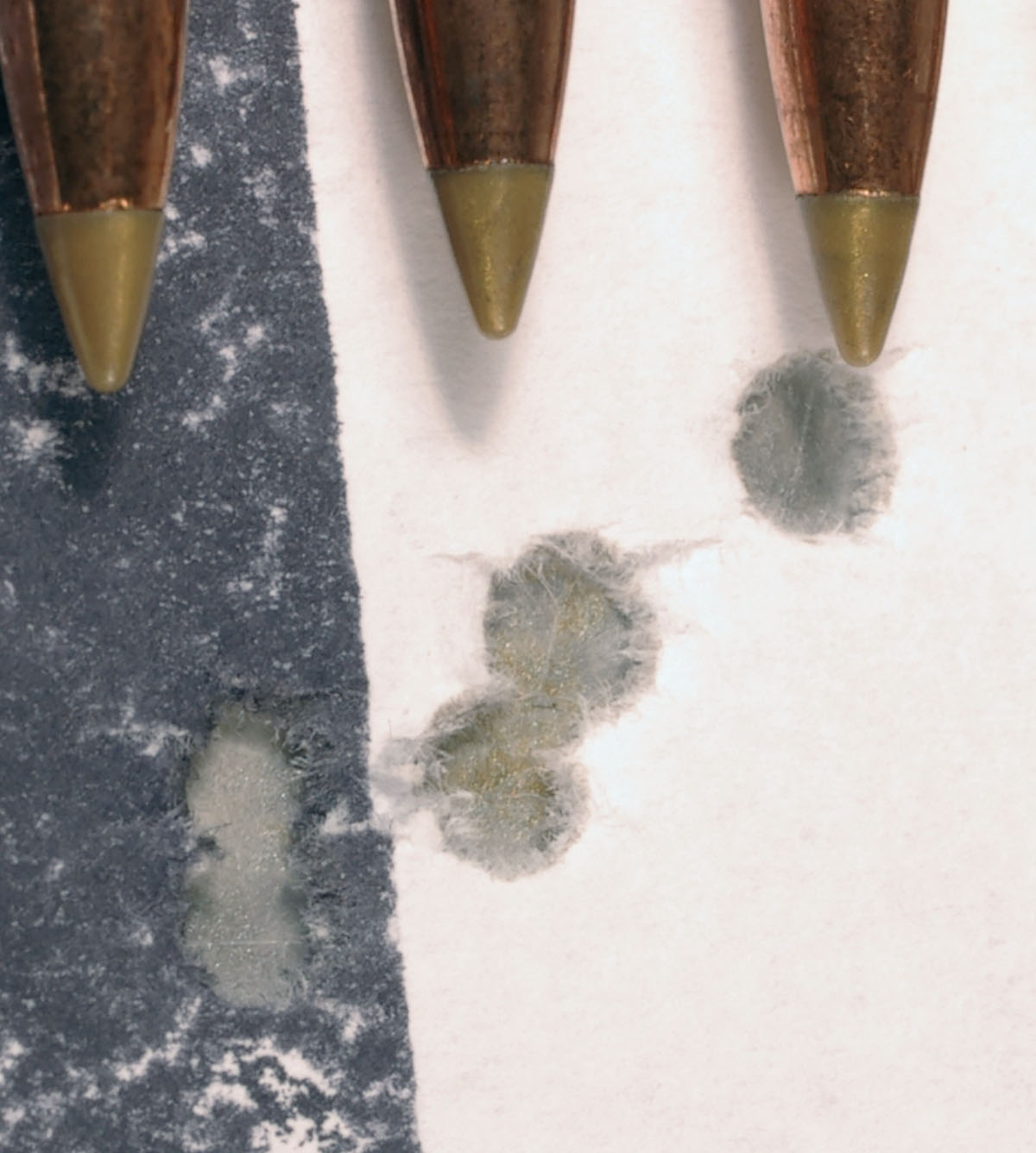

Of course, you’ll want to reload if you’re going to shoot the Fireball a lot. The choices of .17-caliber bullet brands and weights are rather slim. The most common weigh between 20 and 25 grains. Berger makes 20-, 25- and 30-grain hollowpoints. If you have a difficult time deciding on one bullet weight, the Woodchuck Den (woodchuckden.com) makes 21-, 23-, 25-, 27-, 29- and 30-grain bullets. Hornady has been committed to .17-caliber bullets for decades and makes 20- and 25-grain .17s. Compare those choices to .22-caliber cartridges that can be loaded with a wealth of bullets from 35 to 90 grains.

But I went ahead and set my old Ohaus Du-O-Measure to dispense 19.5 grains of Accurate’s 2520 spherical powder and loaded 40 rounds with Hornady 25-grain V-MAX bullets. For five shots, the average velocity was 3,334 fps with an extreme spread of 58 fps. The same powder charge weighed by hand had an average velocity of 3,328 fps and an extreme spread of 101 fps. So using a powder measure worked fine, at least for precisely metering spherical powder.

I used the Redding Deluxe Die Set to size .17 Fireball cases and a Redding Competition Bullet Seating Die. The Deluxe Set includes a neck-sizing die, full-length sizing die and a bullet-seating die. The Compe-tition Bullet Seating Die incorporates a spring-tensioned sleeve to make sure the case mouth and bullet are in alignment when the bullet is seated. I checked a few loaded cartridges, and bullet and case alignment ranged from right on to .002 inch out of alignment.

I did notice a bullet would not fit in fired cases from Remington factory cartridges or my handloads.

Remington cartridges had unfired cases that measured 1.403 inches in length. The cases grew to 1.410 inches after firing and then sizing the full length of the necks in the Redding neck-sizing die. Case stretching was reduced to about .002 inch after firing handloads and sizing cases in the Redding full-length sizing die.

Will the .17 Fireball succeed? It’s miserly with powder yet produces a flat trajectory. Its absence of recoil certainly makes it more fun to shoot than a .22-250, or even a .223 for that matter. For targets and plinking and small game up to the size of marmots out to 300 yards, you’d have to look a long time to find a more user-friendly cartridge. However, some hunters will look at its diminutive bullets and decide they are just too light and stay with larger cartridges.

All I can say is, I really like the .17 Fireball.

.jpg)