The .20 VarTarg

A Varmint Cartridge with Potential

feature By: Stan Trzoniec | August, 12

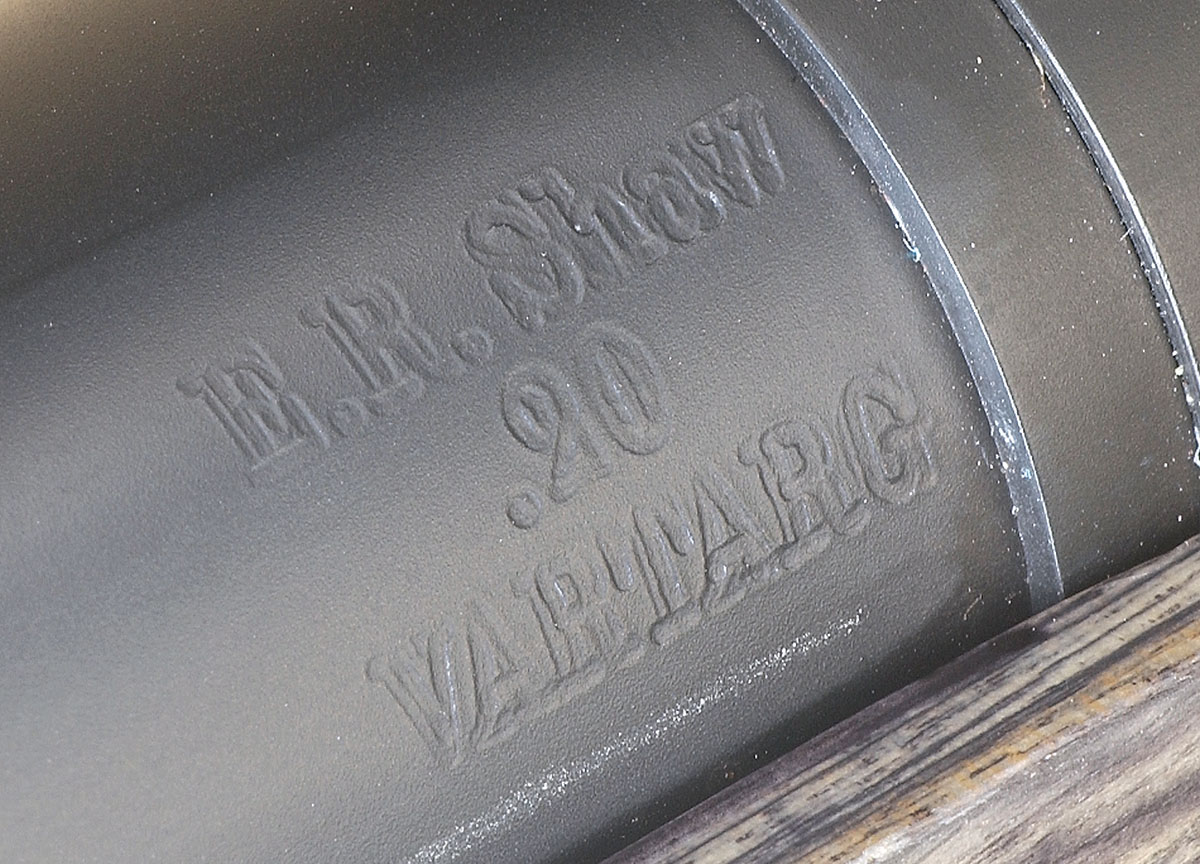

Introduced to American shooters in 1963, the .221 Fireball was offered in the Remington XP-100 single-shot pistol. Basically a .222 Remington shortened to 1.40 inches, it was the perfect item for a short-barreled handgun complete with its B--uck Rogers design and a stock made out of space-age DuPont Zytel, including white inlays and a ventilated rib. It was a major milestone for Remington with around 2,650 fps out of the 101⁄2-inch barrel and a receiver drilled and tapped for scope mounting.

With a 40-grain Speer spitzer in a Contender, I could reach just a tad over 3,000 fps with .5-inch groups at 50 yards. My quest not yet satisfied with the potential of the .221 Fireball, I noticed that Cooper Arms in Montana was chambering this cartridge in its Model 21 bolt-action rifles. I placed an order for a custom .221 Fireball rifle complete with a match grade 24-inch barrel and fleur-de-lis checkering on a good looking piece of wood. With choice loads, that rifle put three shots into .5-inch circles, sometimes less, at 100 yards.

Perusing various journals, I came across an article by Todd Kindler on the .20 VarTarg – the .221 Fireball necked down to .204 caliber. With 32-grain bullets, Kindler claimed velocities around 3,855 fps in a Dakota rifle with a 24-inch barrel.

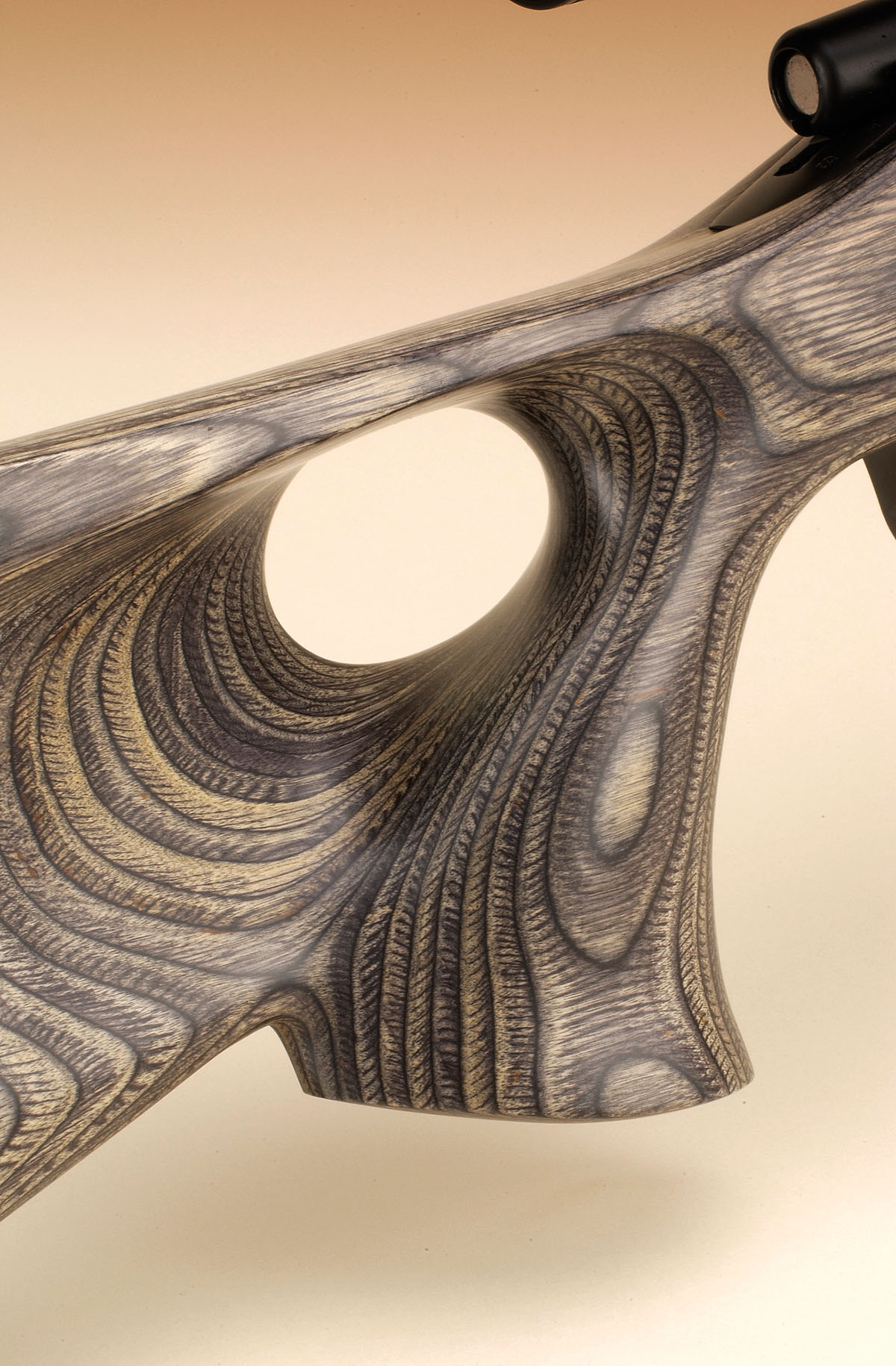

The XR-100 has a laminated stock for all-year hunting and is styled in a modern design, complete with a teardrop pistol-grip cap, rollover cheekpiece, forearm vents and a thumbhole for prone shooting. The rifle is a single shot with a rigid receiver for improved accuracy and an adjustable trigger I tweaked down to 2 pounds.

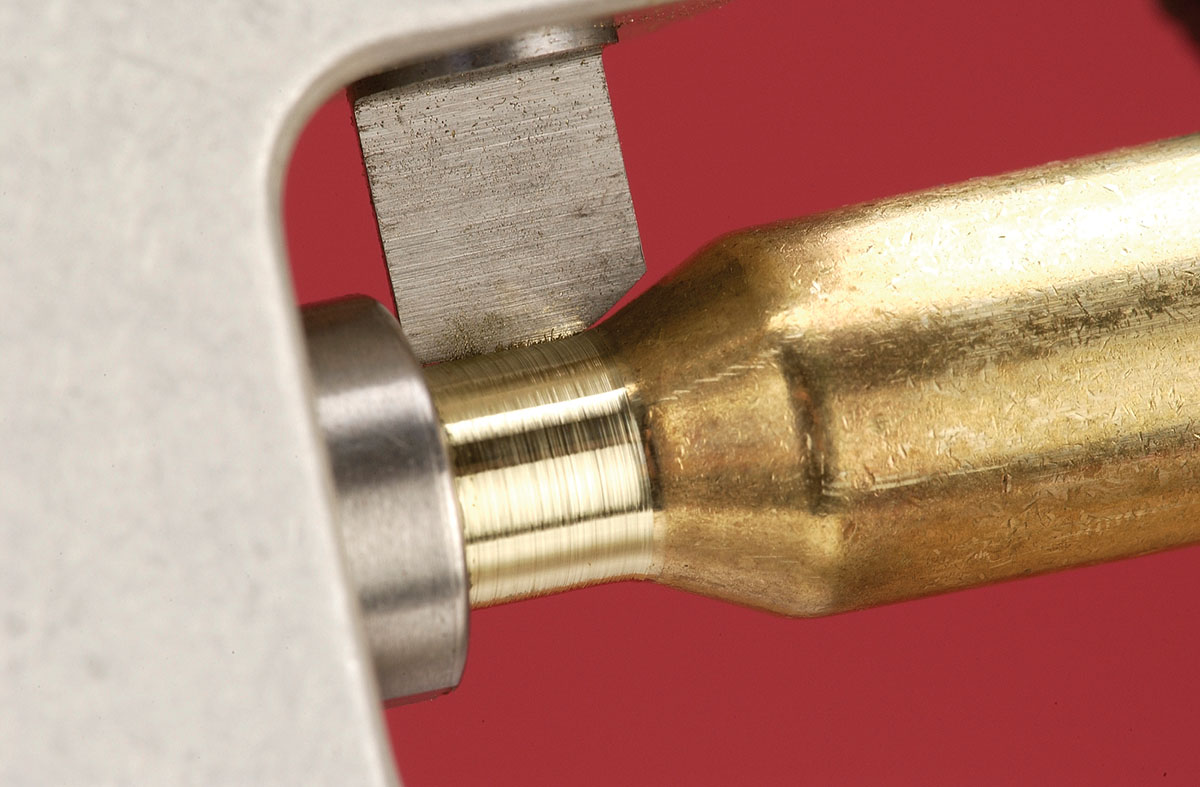

With .221 Fireball brass now easier to get, I collected about 200 cases, putting about 100 aside for future use. The Redding die set came in just about the same time, so the 100 cases were lubed and put through the sizing die to bring the .22-caliber neck down to .20 caliber. I lost one of the first five cases to neck splitting. After that, I lubed the inside of every 10th case.

After the brass was necked down to .20 caliber, each case was run into a neck mandrel to square up the neck and ensure the case fit the neck turning mandrel supplied with the tool. This is a quick operation and follows full-length sizing. All the cases were then dropped into the Iosso case cleaning solution, returning them to factory fresh.

For those who might be turning necks for the first time, a couple of hints might be helpful. After adjusting the cutting depth, and for uniformity, advance the case on the mandrel and toward the blade in a clockwise direction. Never butt or jam the case neck against the cutter, as this will only promote nicks on the mouth of the case that can be difficult to remove. You’ll want to develop a turning speed that is comfortable and one that does not look like you are trying to thread the neck of the case. Slow does it with the ultimate goal of a smooth neck from the mouth to the shoulder. Make sure you turn the neck up fully to – but not touching – the shoulder. My tool was cut on an angle so it wouldn’t touch the shoulder. If you do use a tool that cuts into the shoulder, stop at once or risk a weak spot and short case life. When you reach the end of the cut, keep turning the case as you start to withdraw it from the tool.

You’ll need a neck sizing die to keep the neck in check after fireforming. I ordered mine through the RCBS Custom Shop. Send them an empty but fired case so they can do the job right. When I got the die and neck-sized fired cases, inside diameter of the cases came out to .202 inch – perfect to secure a .204-inch bullet.

After going through the initial neck sizing and turning, check the length of the case before loading and trim if necessary. The .221 Fireball cases were right on the money going in, but after the initial fireforming session, they grew to 1.410 inches but were still under the 1.415-inch maximum. Mine were trimmed to 1.405 inches, and CCI BR-4 Small Rifle Benchrest primers were used exclusively.

Powder charges came from a number of sources, including Todd Kindler (The Woodchuck Den, 11220 Hilltop Road SW, Baltic OH 43804) and from the excellent ballistic program “Load From A Disc” by Wayne Blackwell (9826 Sagedale Drive, Houston TX 77089). While some of the published data seems to dote on a few powders that work well, I jumped a step ahead and offered more selections. I’m not suggesting all are minute-of-angle (MOA) loads, because those that work well in one gun might not work in another. Looking at the results shows that all the powders fit into one cate-gory concerning burning rate with most falling in the 18.0- to 20.0-grain range. For those interested in going past this point, the .20 VarTarg (in case volume) is good for around 23.0 grains of water.

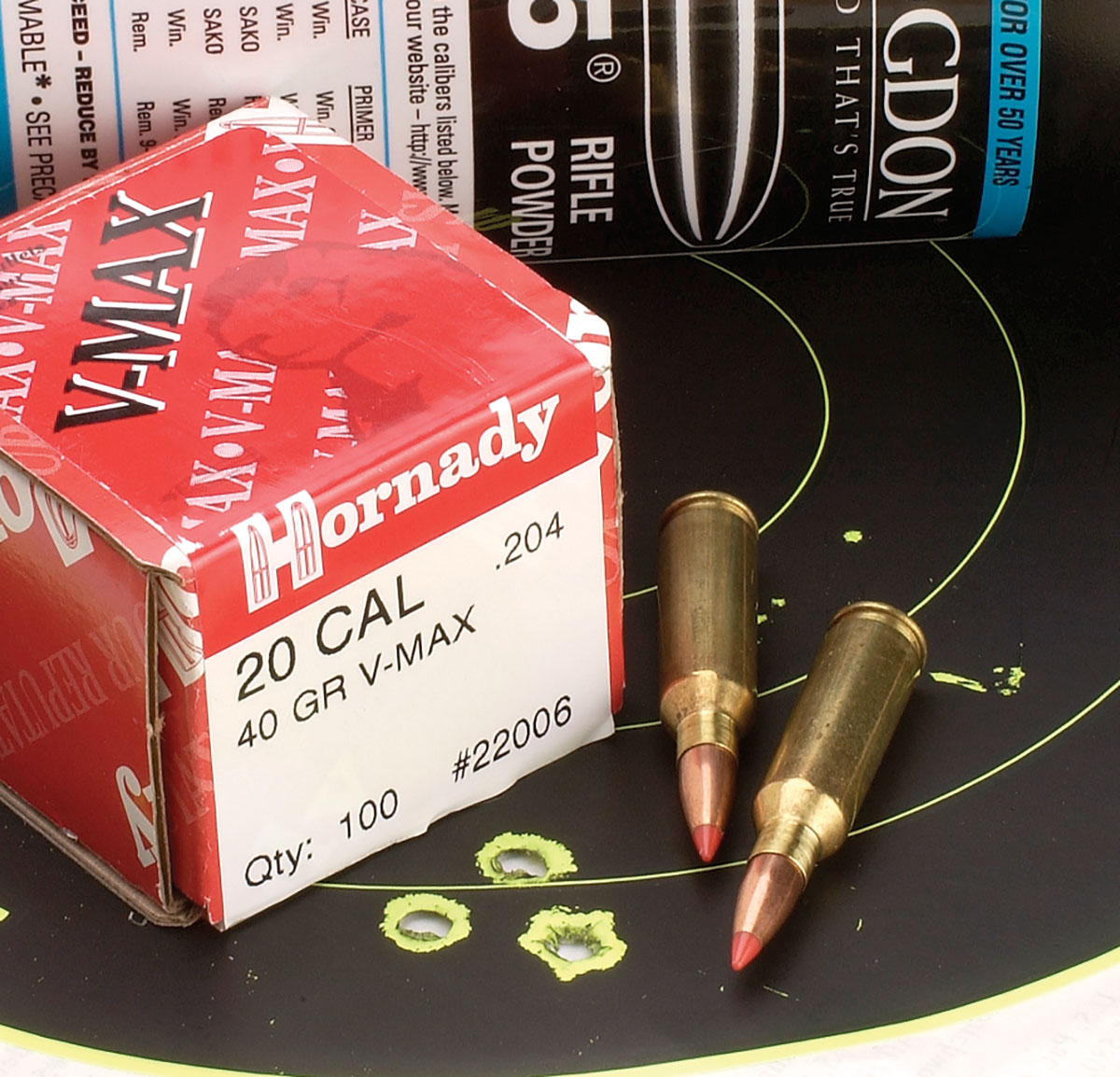

Bullets included Hornady’s 32- and 40-grain V-MAXes. With the woodchuck season already underway, I wanted to keep things relatively simple with more serious testing reserved for other bullets when the hot weather passed in September and October. To finish the loading session, all powder charges were hand-trickled for uniformity, bullets were seated at 1.940 inches overall loaded length, which worked out perfectly for the Remington-Shaw combination.

Overall, I’d go with 18.5 grains of VV-N120 for .75-inch groups followed by 19.0 grains of H-4198 at 3,700 fps with the Hornady 32-grain bullet. Hodgdon’s H-4198 gave .75-inch groups, while its counterpart, H-4895, went just under an inch. Finally,for my woodchucking needs, the 40-grain Hornady sparked by 20.0 grains of H-335 gave .5-inch clusters at the cost of a slightly lower velocity reading, but I’ll take it.

My obsession with .17- to .22-caliber wildcats means more shooting with less pain. The Remington rifle, equipped with the Shaw barrel and topped with a Bushnell scope, brought the recoil factor of the .20 VarTarg to around one foot-pound on my shooting shoulder. Additional benefits would include less noise, longer barrel life (since it uses a smaller amount of powder) and less fouling.

Briefly, I like the .20 VarTarg. It was a challenge to gather all the parts to make this .20-caliber cartridge a reality, and I’m not finished yet. Most of the shooting came at the end of summer, so I have the cooler weather to do more in the way of research and testing of this very interesting wildcat. I look forward to it.

.jpg)