.22 Remington BR

An Unheralded Wildcat

feature By: Stan Trzoniec | August, 12

Although the .22 BR (BenchRest)Remington cartridge has never been that popular with hard-core varmint or small game shooters, it is, nevertheless, easy to load and fun to use. I call it my “no-sweat” wildcat.

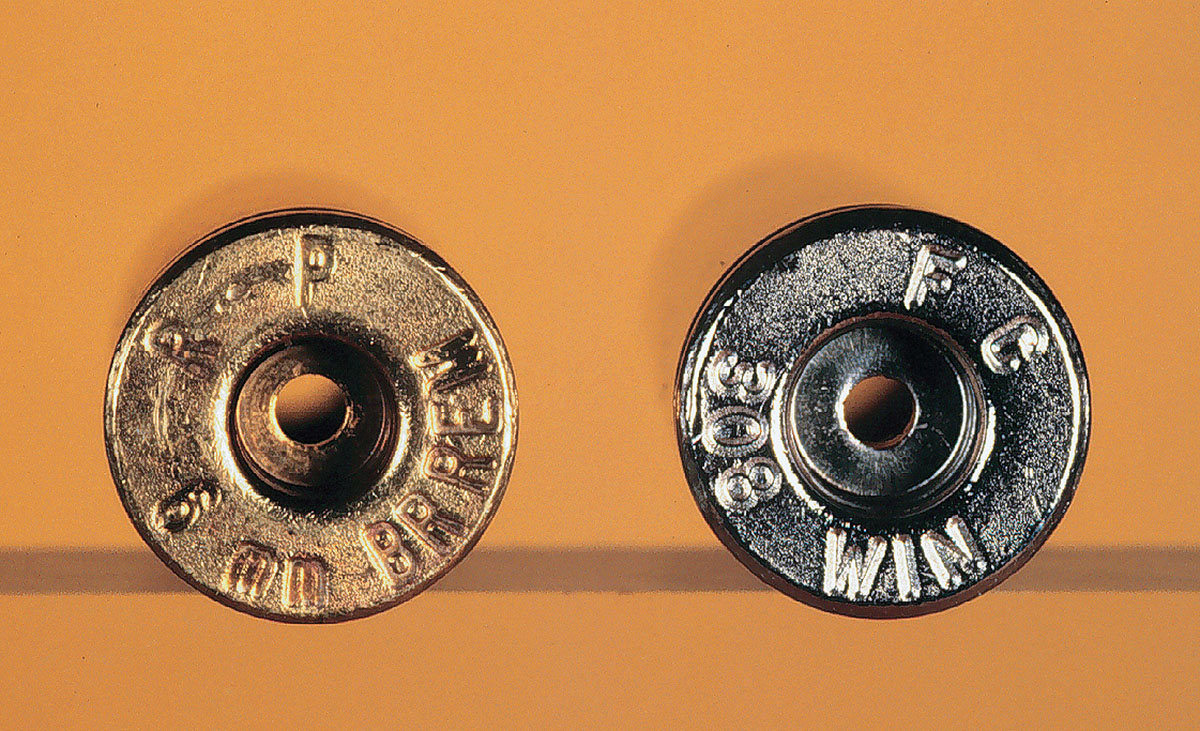

There were some other problems, however, that made one wonder where Remington was really going with all this. In the year of introduction (1978), the parent company introduced a “universal” benchrest case (called the UBBR) in the familiar .308 length and profile. According to references, this universal .308 Winchester case – the word “Winchester” was dropped for obvious reasons – was made with thinner walls and specially annealed for case forming. According to Remington all you had to do was shorten the case and simply neck it down to .22 caliber. As mentioned, the case was made with a small rifle primer pocket in an effort to produce more uniform powder ignition in a smaller case.

In the same year, a 40-XBR target-type rifle was chambered in the .22 BR; in 1979 the same rifle was chambered for the 6mm BR, which was again nothing more than the .308 UBBR case shortened and necked to .243 inch. In 1980 the XP-100 was brought on line and chambered for the 7mm BR, again using the .308 UBBR case necked to .284 inch. Strangely, though, with all this hoopla, not a single loaded or formed factory case was made available until almost a decade later when the 7mm BR and the 6mm BR were brought out in factory loads in 1988 and 1989, respectively.

So in all of this, what happened to the lonely .22 BR? While it has seemed to have vanished into the great beyond, the .22 BR Remington can be revived, but hurdles must be overcome. First, you have to form or neck your own brass. That is no problem if you know where to look for brass. The second is a rifle – again not a problem, and I’ll show you the easy way around both.

Before all that, however, let’s compare the .22 BR with a few close wildcat relatives. With safe reloading practices, you can, with off-the-shelf 50-grain, .224-inch bullets, raise the .22 BR to around 3,700 fps. The .22 PPC can churn up about 3,418, while the .22 CHeetah (which might not be a fair comparison as it exceeds the famed .220 Swift by about 10 percent) will hit close to 3,900 fps depending on barrel length and outside temperature. Still, to get a closer prospective using readily available commercial ammunition and still loading that 50-grain bullet, the .222 Remington can edge up to 3,140 fps, the .223 Remington, around 3,240 fps and one of my favorites, the .224 Weatherby, about 3,700 fps with 24-inch barrels.

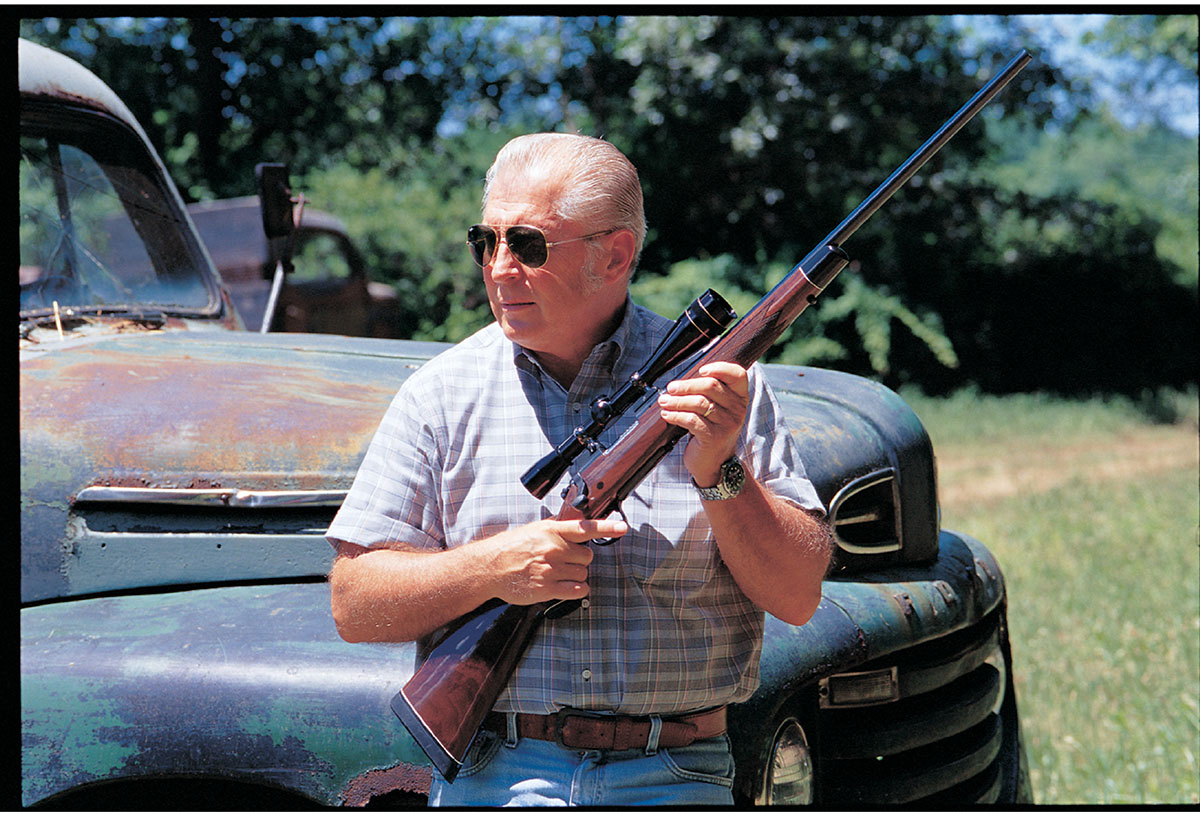

With all that in the open, we can now start on the project. While nothing is chambered for the .22 BR on the commercial market, the first step is to check your inventory or purchase a Remington Model 700 short-action rifle that is chambered in the .22-250 Remington, .308 Winchester, .243 Winchester, etc., all with a rim size of .473 inch. My first choice was the .22-250 Remington because it was in stock, and the good folks at Remington agreed to help participate in the project. But why a Remington Model 700 BDL? I’ll explain in a minute.

While E.R. Shaw makes barrels in various contours, diameters and lengths, the one that turned my head is the category in which Shaw will supply a barrel, polish and blue it and match it exactly to current Remington barrel contours. In effect, you can send your barreled action to Shaw, have a new barrel installed in a new and different cartridge and when you get it home it will drop into that same stock without any modifications, cutting or enlarging the barrel channel. Is that great or what?

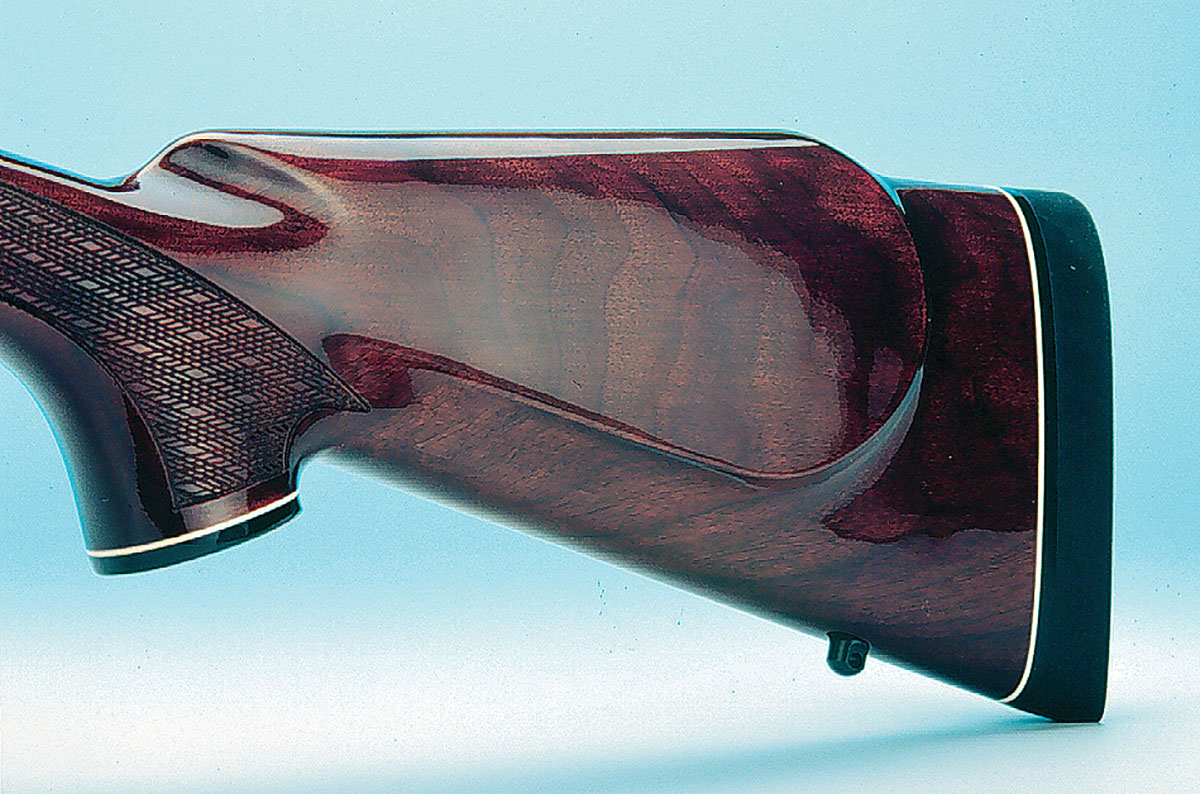

That’s exactly what I did, and it all worked perfectly. In fact, if you’re not in the mood for the .22 BR Remington, how about the .257 Ackley, 7mm JRS or choose from a list of popular or wildcat offerings that is too long to list here. By this time the stock came back from having a recoil pad installed (my crusade for deleting those horrible plastic buttplates never ends). I tweaked the trigger a bit and installed a Leupold 12x scope in Burris high gloss rings installed on the rifle with Redfield bases.

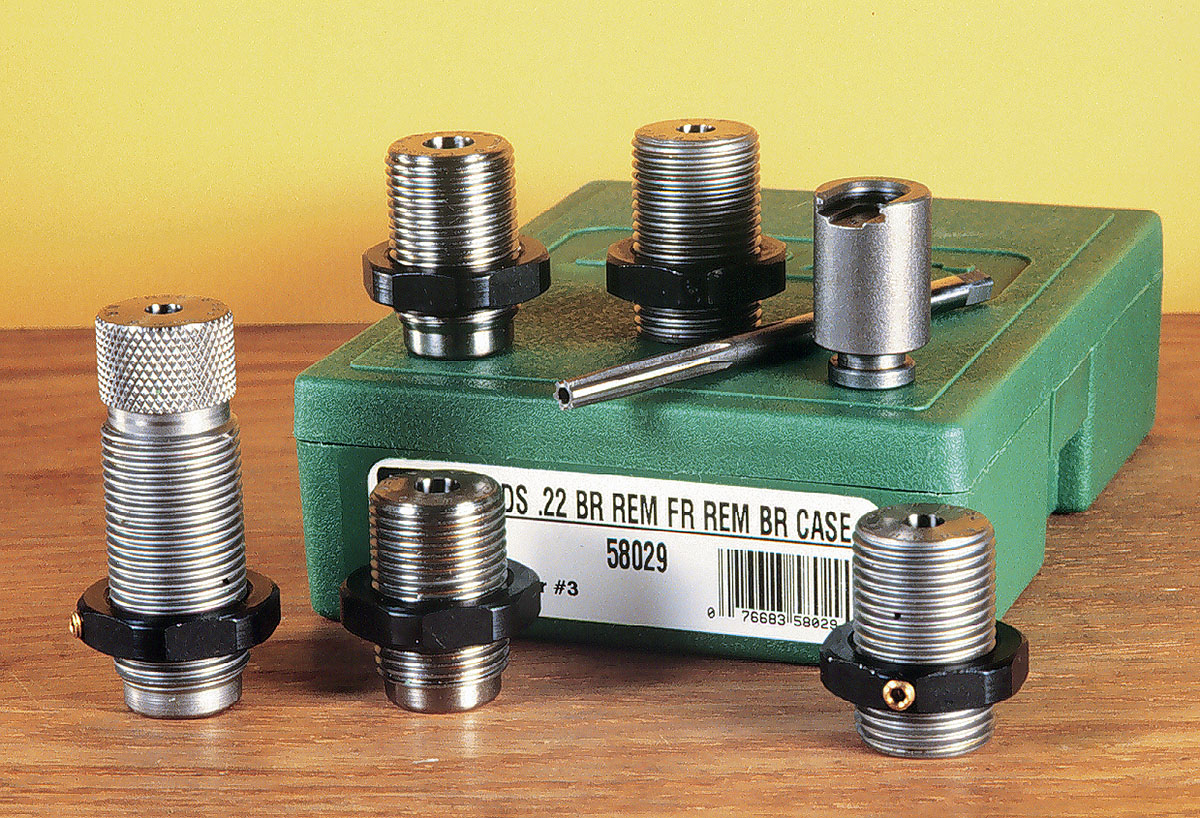

Forming .22 BR brass can be tackled a number of ways. As mentioned, if you simply can’t get 6mm BR or 7mm BR brass, you can, ina pinch, use the .308 Winchester case, keeping in mind that accuracy may suffer with a large rifle primer. Again, Jim Stekl tells me that using a case with a large primer is fine for varmints, but for the nth degree in accuracy (read benchrest), cases with small rifle primers are still best. For forming .308 to the .22 BR case, you’ll need the RCBS CFDS (case forming die set). This set is complete with an extended shellholder and neck reamer, but I’d really try to purchase 6mm BR brass before going in that direction.

The easy way is, of course, to purchase 6mm BR brass and order .22 BR dies and simply run each case into the die. In one deft motion you have a .22 BR case ready for action with the exception of some minor case trimming. Neck thickness does not change with this minor forming (from .243 to .224 inch), and the resultant case length is 1.560 inches. Trim all cases to 1.510 inches, and do not let them “grow” beyond 1.520 inches. Cham-fer the inside and outside of the mouth, install a good benchrest small rifle primer like the Rem-ington 71⁄2 or CCI BR-4, and you’re ready for the next step.

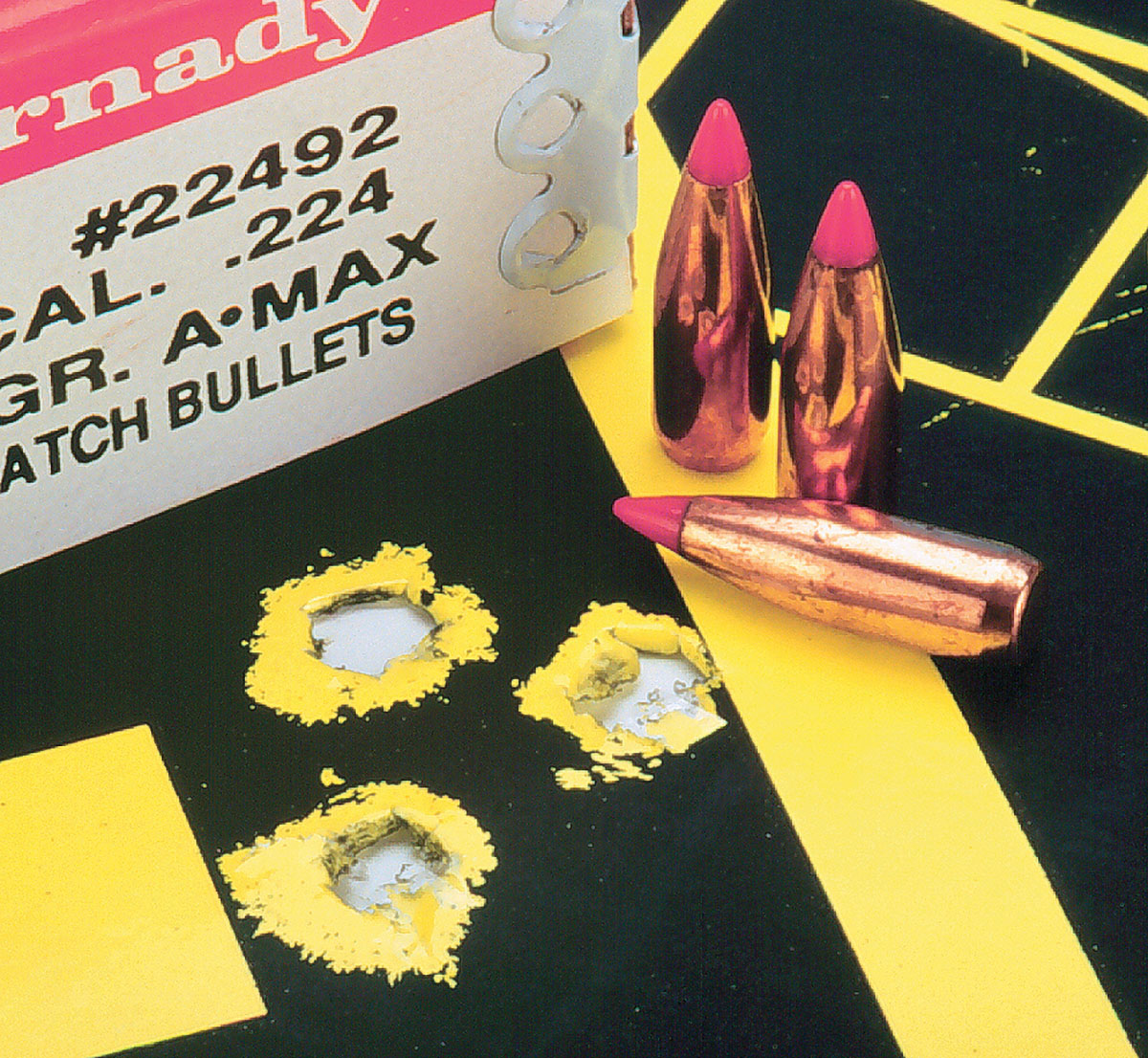

Ballistic Tips to 70-grain softpoints. I was never a big fan of heavy 70-grain bullets in .224-inch guise, so my main interest, therefore, lies with bullet weights from 40 to 55 grains. One heavy bullet, a 63-grain Sierra, is shown for comparison.

metered easily, while H-335 and BL-C(2) flowed like silk through either measure as did Accurate XMR-2015 and AA-2460. When looking at case volume, notes show that Varget filled the case with 33.5 grains to the point of mild compression, and examples like H-322 (29.0 grains), AAC-2460 (32.5 grains) and XMR-2015 (30.5 grains) filled the case to the neck/shoulder juncture. Favorites like H-322, H-335 and BL-C(2) generally provided slightly less load density.

Bullet seating is almost a personal matter and borders on hear-say and sorcery, depending upon whom you talk to. In some pet rifles, seating bullets so they just touch the lands works fine; in others, seating the bullet at least one diameter into the case works even better. In the .22 BR, at least one-half to a full bullet diameter seating depth was employed – the former on lighter projectiles, the latter on bullets 55 grains and up. This allows for flawless feeding in the rifle while still allowing for a good measure of accuracy without unneeded or unwanted pressure problems.

The other problem that might arise when chambering a rifle for a cartridge that hardly exceeds 2.00 inches is feeding. In the .22-250 Remington action, placing the .22 BR cartridge in the center of the follower allowed for faultless feeding with all bullet weights. When the magazine was loaded with three rounds, they fed into the chamber if the bolt were pushed very slowly and the cartridges were stacked perfectly one on top of the other.

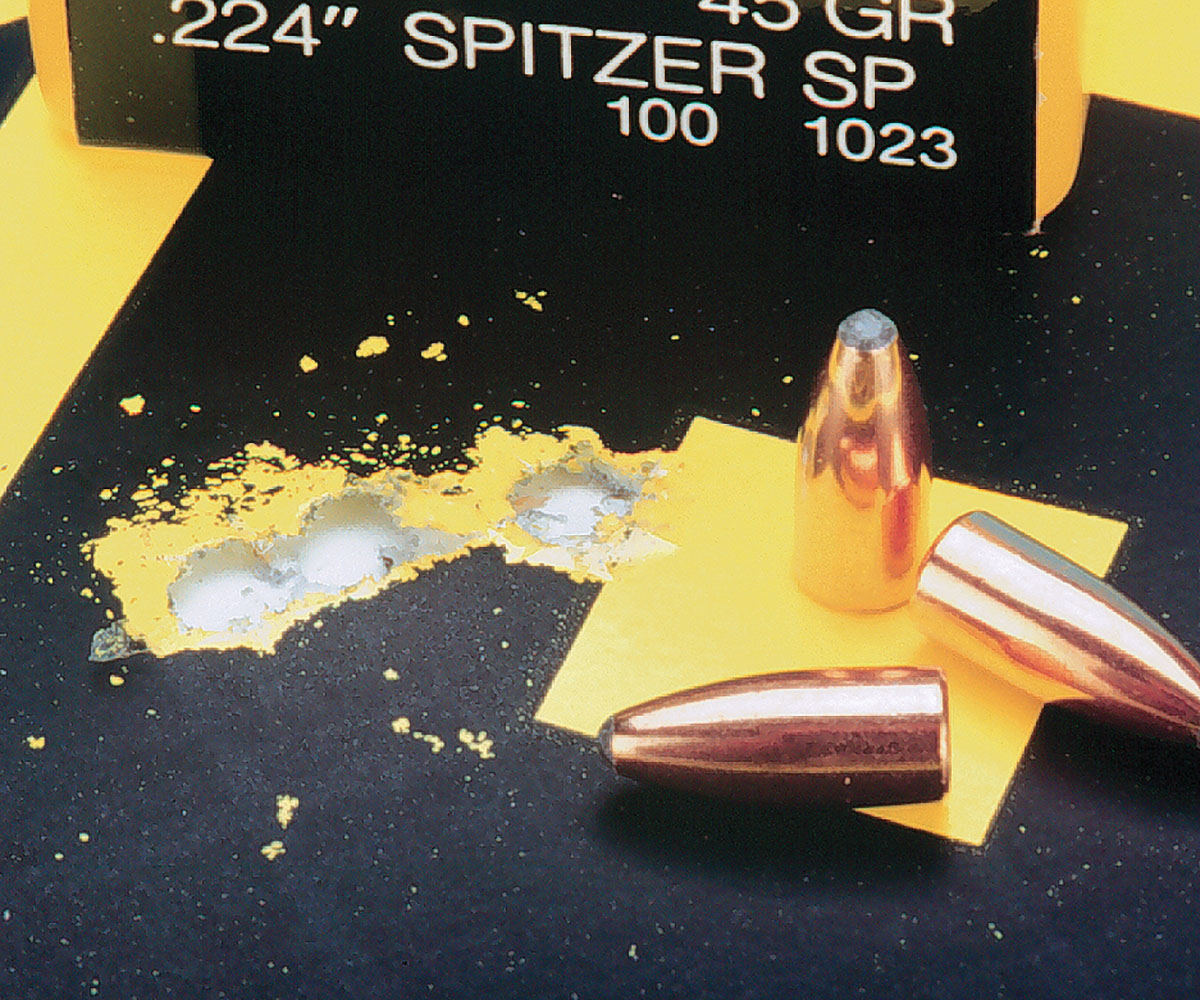

As I progressed, some favorites started to appear. Hodgdon’s H-335 was the winner on a number of occasions with velocity around 3,964 fps and group size just a tad over .5 inch using a charge of 33.0 grains under a Speer 45-grain spitzer. Still another was 31.0 grains combined with a Hornady 55-grain V-MAX. While velocity was down to 3,603 fps, accuracy was still under that magical inch. Hodgdon’s H-322 did well with the Sierra 52-grain hollowpoint boat-tail match using 28.5 grains for 3,352 fps and one-inch groups. Topping that was a slight increase to 29.0 grains for 3,439fps with an average group size of 5⁄8 inch. Of bullets in the 60-grain class and above, I’d go with that Sierra 63-grain semipointed over 33.0 grains of BL-C(2). Velocity was 3,433 fps.

In the end, working with the .22 BR turned out to be an enjoyable experience with a cartridge that may have already been put to rest. Benchrest shooters really like the .22 BR, and as a casual varmint shooter I can see why. Velocities are high, groups are tight and this shooter is happy. What more can a guy ask for?

My thanks to all who helped in this project, including Remington, Leupold, Burris, E.R. Shaw, Jack Heath and, of course, Jim Stekl.

.jpg)