.220 Swift

New Bullets, New Powders

feature By: Ken Waters | August, 11

It’s been more than 20 years since I issued my last “Pet Loads” report on the .220 Swift. In that interval a considerable number of new powders and bullets have appeared while, at the same time, the Swift seems to have gained new followers. I also sense a change in emphasis away from the original barrel-straining, 4,000+ fps 48-grain loads to slightly heavier, more aerodynamically shaped bullets with flatter trajectories and better retained energies.

Thinking along those lines, I decided to undertake an up-to-date series of range-tested load trials with a standard weight hunting rifle. As before, a Ruger Model 77 with 24-inch factory barrel was used, our loads being based upon this rifle’s demonstrated performance with gradually increased loads. As such, ballistics might differ from those shown in popular manuals.

Experienced handloaders, aware of the differences between the reactions of individual rifles, know that before arriving at the best combination of bullet, powder and load for their purpose, it will be necessary to try several prescriptions in their rifle. Velocity as well as accuracy will also play a part in load selections.

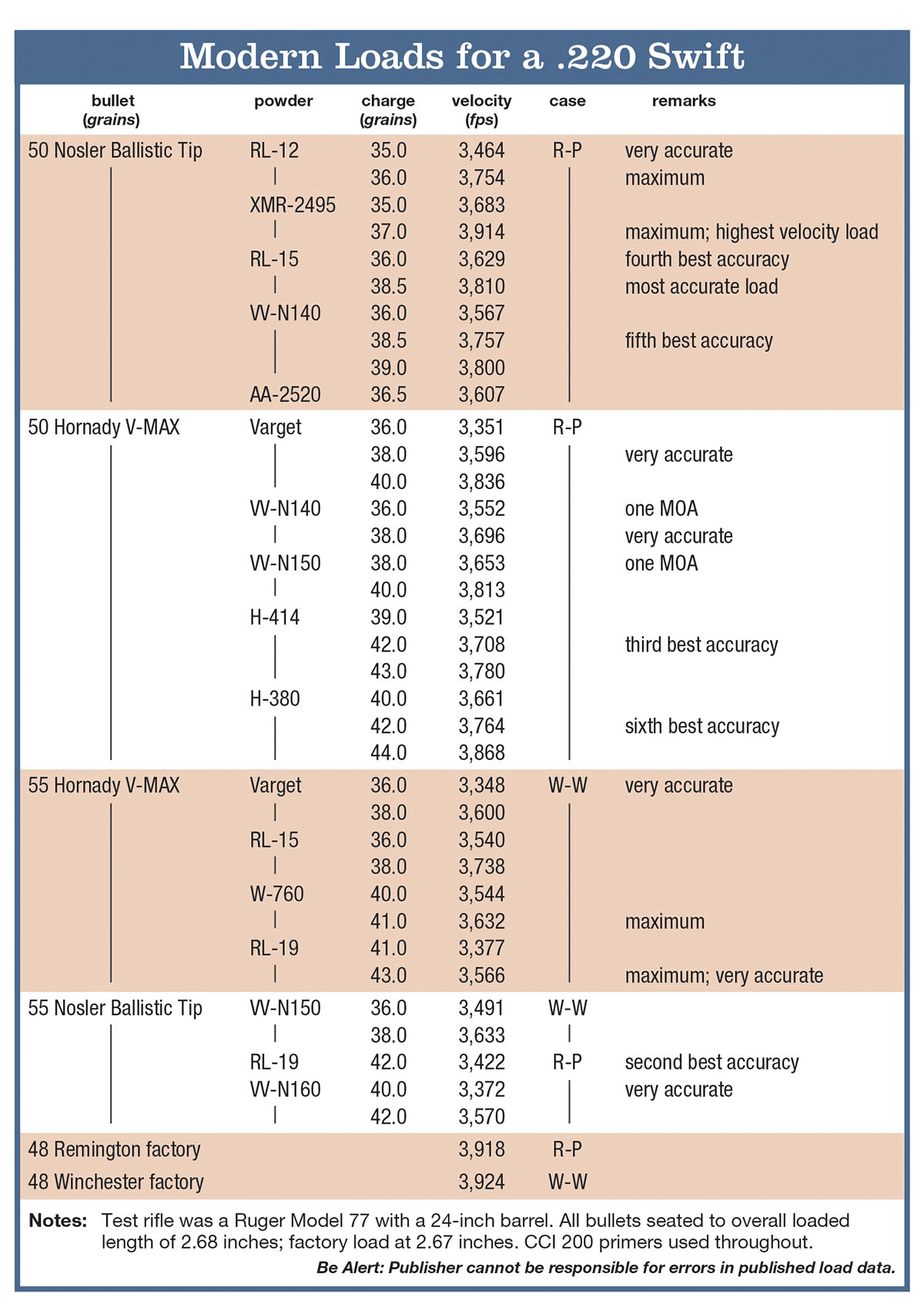

It is to assist in this process of selection that I include a table showing a variety of loads with different bullets. The hunter or varminter may eventually settle on a single load combination or two, but an avid handloader will frequently continue to seek improvements, in effect, competing against himself. Range-tested loads can be helpful in such a pursuit by indicating which have proved best in the writer’s rifle.

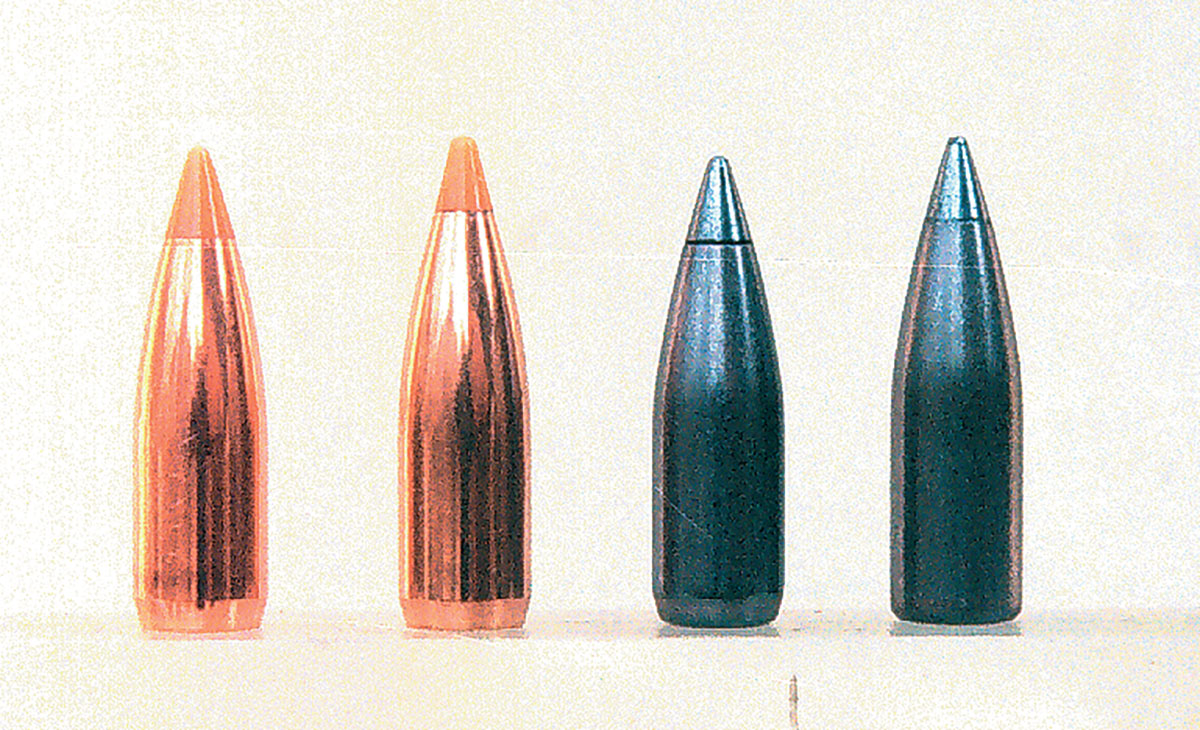

On that premise, therefore, I chose Nosler Ballistic Tip bullets of 50 and 55 grains, plus the Hornady V-MAX in the same weights. With them you will find a total of a dozen powders, nine of which are of fairly recent vintage.

First, I believe it’s essential that we decide what the Swift is all about – and is not. It is the supreme long-range varmint caliber, combining very high velocity, flat trajectory and fine accuracy to an unmatched degree. There is simply no better factory cartridge for the purpose.

Let’s recognize, however, that in general, the .220 Swift is not a big game round. Power it generates, but has neither the bullet size nor weight to ensure a clean, humane kill under less than favorable conditions, at least with the original factory 48 grainer or the usual 50- or 55-grain varmint bullets.

Having experienced the performance of high-velocity .224-inch bullets on deer (see my “Pet Loads” report in Handloader No. 7 on the .224 Weatherby Magnum), I knew that even with classic bullet expansion to twice its diameter, unless a hit is made in either the heart/lung or spinal area, the dramatic effect of a small, high-speed bullet, so obvious on varmints, is absent on even the smaller big game species.

Carry a .22 centerfire on a big game hunt and sooner or later you’ll be tempted to take a shot you shouldn’t. When the trail-up which follows fails and a fine animal suffers a torturous death, place the blame where it squarely belongs. Even the best varmint cartridge doesn’t make a good deer round!

If anything is capable of turning the .220 Swift into an adequate deer round, however, it is the new 60-grain Nosler Partition at around 3,600 fps. I’d still rather have a 7x57mm Mauser or .308 Winchester for an angled shot or one through light brush, but the superior construction of this new specialized bullet increases penetration and bone disruption.

That said, let’s view this round in its proper roles of varminter, running deer targeter and pest eliminator where its assets are unquestioned.

Factory ballistic tables for the Swift have changed. Gone is the old classic 48-grain Winchester loading rated at 4,110 fps muzzle velocity, replaced by a pair including a 40-grain Ballistic Silvertip at 4,050 fps and a 50-grain Pointed Soft Point (PSP) at 3,870 fps from 24-inch barrels.

Remington’s 50-grain PSP is listed at 3,780 fps, as is its 50-grain V-MAX boat-tail. Federal tables show a 50-grain Sierra exiting at 3,830 fps, but its 55-grain loading with Trophy Bonded Bear Claw is down to an even 3,700 fps. Hornady lists a 50-grain Spire Point at 3,850 fps, plus a 60-grain hollowpoint at 3,600 fps.

Those figures are only about 100 fps faster than the .22-250 Remington with same weight bullets! What has happened? Were the old ballistics unrealistic, possibly taken from a 26-inch barrel, or were chamber pressures of the original loads considered too high? While not knowing for certain which it was, I suspect barrel length was at least partly involved, as both Winchester and Remington 48-grain factory loads exceed 3,900 fps from my 24-inch barreled Ruger Model 77.

While the Old Champ has lost some of its former prestige, the new sharper-nose V-MAX and Ballistic Tip bullets have greatly improved the Swift’s downrange performance, increasing retained velocities at 200 yards by a substantial 300 fps and 400 fps additional at 300 yards. So there’s still no flatter-shooting American factory load to 300 yards or a more effective pest eliminator.

Another factor seldom mentioned that might affect velocity is rifling twist rate. Ruger Model 77s, Winchester Model 70s, Remington Model 700s and Savage 112-V Swifts have a one-in-14-inch twist, while regular Savage 112s (for some reason) are given a steeper one-in-12-inch twist, as do Thompson/Center rifles.

Unfortunately, Swifts have long been criticized as barrel-burners, and this claim, too, needs to be addressed. Barrel life relates more to heating than to bullet velocity, erosion being the product of high barrel temperature. Allowing the barrel to cool down after firing not more than three shots in succession will extend the life of a Swift’s barrel considerably. Better modern barrel steel has helped materially in this regard, and up to 3,000 rounds are now possible without serious loss of accuracy, but again overheating should be avoided.

Much is being said these days about bore cleaning, overly much in my opinion. Lest this statement be misconstrued, allow me to explain that I’m all in favor of a careful cleaning of any rifle’s bore after a shoot, whether it be on the target range or at game.

What I strongly disagree with are those published advisories to use an abrasive paste for removing copper streaks on the lands. While a sparing use of one of those pastes might be in order when attempting to rescue a rusted or sadly neglected barrel, to assault a fine bore by repeated scrubbing with an abrasive – one writer even opined that a dozen passes wouldn’t do any harm – is the height of foolishness.

My gunsmith told me of two barrels that had been worn oversize to a measurable extent and ruined by such overzealous scrubbing to remove copper color on the lands. Our rifle bores, including the Swift, receive no such violent treatment and, despite an occasional appearance of copper coloring, still group well under one minute of angle (MOA). Nor have I found barrel fouling in the Ruger Swift to be

any greater than in a Ruger .22-250 Remington.

Of course, the lower velocities of both commercial and those handloads parroting .22-250 Remington rounds will help in reducing bore fouling and extending barrel life.

Two practical ways in which Swift owners can assist in achieving those objectives are first to use 50 grain and heavier bullets with their lower velocities, they being less wind sensitive as well; and secondly to recognize that shots on varmints inside 200 yards don’t require maximum loads.

Someone has referred to down-loading this cartridge as being “counterproductive.” Nonsense! Just why Swift loads throttled down to around 3,500 fps would be any less effective on midrange ’chucks than a .223 Remington at 3,300 fps is beyond me. Several such loads that have proved very accurate are included in the table of loads.

Reloading for a .220 Swift, while a bit more involved in one respect, isn’t at all difficult. My reference here is to case neck wall thickness, which varies excessively in this caliber, affecting the clearance of case necks from a rifle’s chamber.

Measuring the outside diameter of loaded factory Swift cartridge necks, my micrometer read .260 inch on Winchesters, .256 to .257 inch on Remingtons and only .252 to .253 inch on Normas. That’s a considerable difference that could well affect chamber pressures and accuracy.

Redding makes neck-sizing bushings in .001-inch increments to permit handloaders to select a bushing best suited to the cases being used, advising that from .002 to .003 inch be subtracted from the outside diameter of factory loaded cartridges, thereby allowing for brass springback after sizing. By thus matching the bushing size to the cases being used, case necks will be correctly sized for a uniform tension on bullets.

The bushings are not the only reason for improved accuracy, however. Some of the credit must go to the new bullets. On average, the Ruger is making smaller groups than it did 20 years ago, and the Nosler Ballistic Tip and Hornady V-MAX bullets are, in a word, great! Typically shooting into .75 inch or less, the 50-grain Noslers captured first, fourth and fifth place accuracy, while 50-grain Hornadys were claim- ing third and sixth places.

With a few exceptions, 55-grain bullets of both makes were slightly less noteworthy, though the Noslers averaged one inch, and one load combination pitched into an impressive 3⁄8 inch, taking second place. The 55-grain V-MAX failed to make as small groups as its 50-grain siblings but well might prove proportionately better at 200 yards and beyond, especially in a wind. I’d be content to use any of the four bullets where it counts if allowed to have my choice of powders.

It can’t help but get your attention, for instance, when records of the six most accurate load combinations reveal that Reloder 15 was used in two of them and Reloder 19, H-414, H-380 and Vihtavuori N140 in one each. XMR-2495 gave the highest velocity, followed closely by

H-380. My favorite load consists of 50-grain Nosler Ballistic Tips over 38.5 grains of RL-15.

Let me note here that, following my usual practice of judging comparative pressures based on micrometer dimensions of fired case pressure rings, none of our handloads exceeded the expansion of Winchester and Remington factory cartridges, although those loads I’ve labeled maximum measured the same .4440 inch. No cases showed any evidence of strain, and primer pockets remained tight despite repeated firings.

Best not crowd the upper load limits until you’ve become familiar with your Swift and watched its response to small increases of charge weights. Chances are you will find finest accuracy occurring with loads giving from 100 to 200 fps less than top velocities. In the test rifle, those speeds ranged from 3,629 to 3,810 fps with 50-grain bullets and from 3,566 to 3,733 fps with 55-grain pills. Groups opened some when velocity of the 50 grainer was raised above 3,900 fps.

To recap, pay close attention to the Swift’s case in particular. Use cases of the same make (better still of the same lot), size necks for proper tension on bullets and make sure to keep them trimmed at or below maximum length of 2.205 inches, deburring after trimming. Also, clean the scale from primer pockets.

In view of the high pressures of this cartridge and a concurrent potential for brass to flow, gradually thickening neck walls, my suggestion would be to discontinue using cases for full-power loads after five firings, as a safety precaution.

Once cases have been cared for as outlined, loading for a .220 Swift is much like any other high-power cartridge. It’s a great, old round that never had to put up with rifles of deficient strength so can still stand tall even among modern calibers.