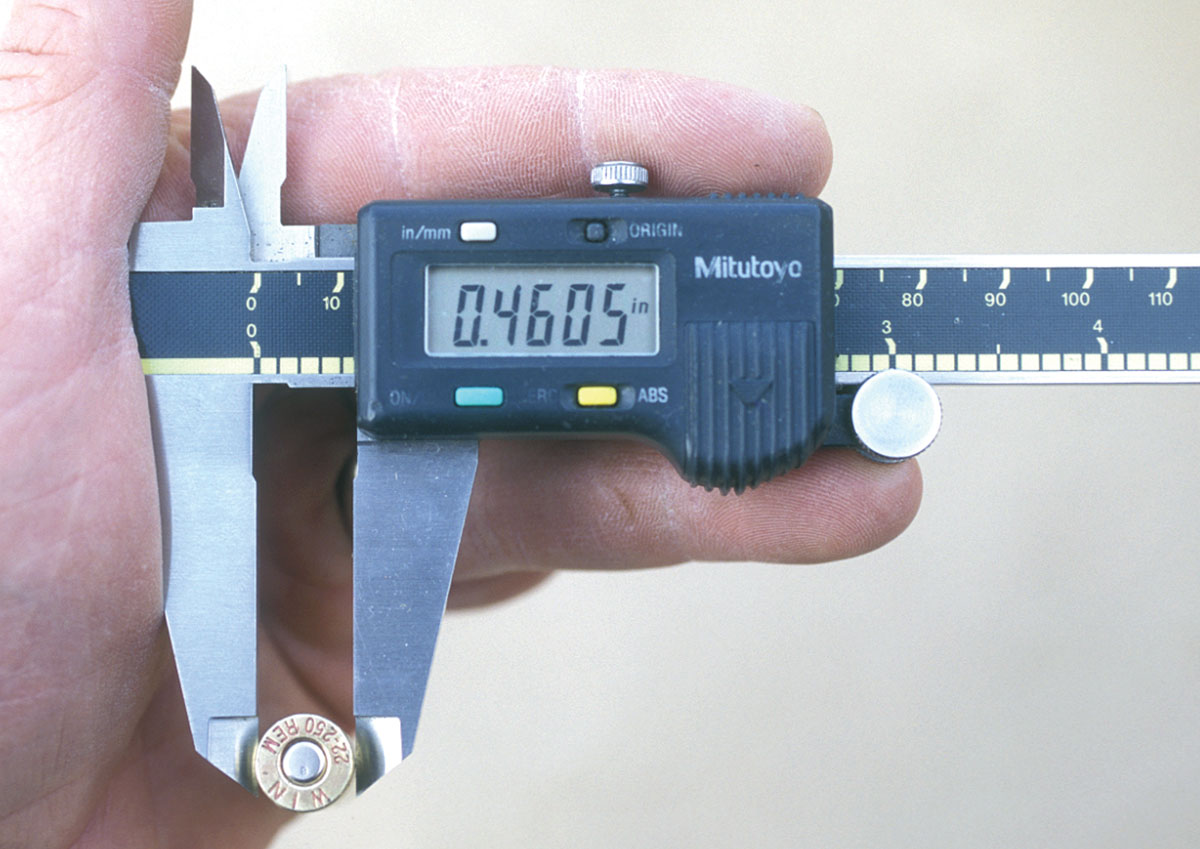

Handloading the .22-250

Performance Loads from A to Z

feature By: Brian Pearce | August, 11

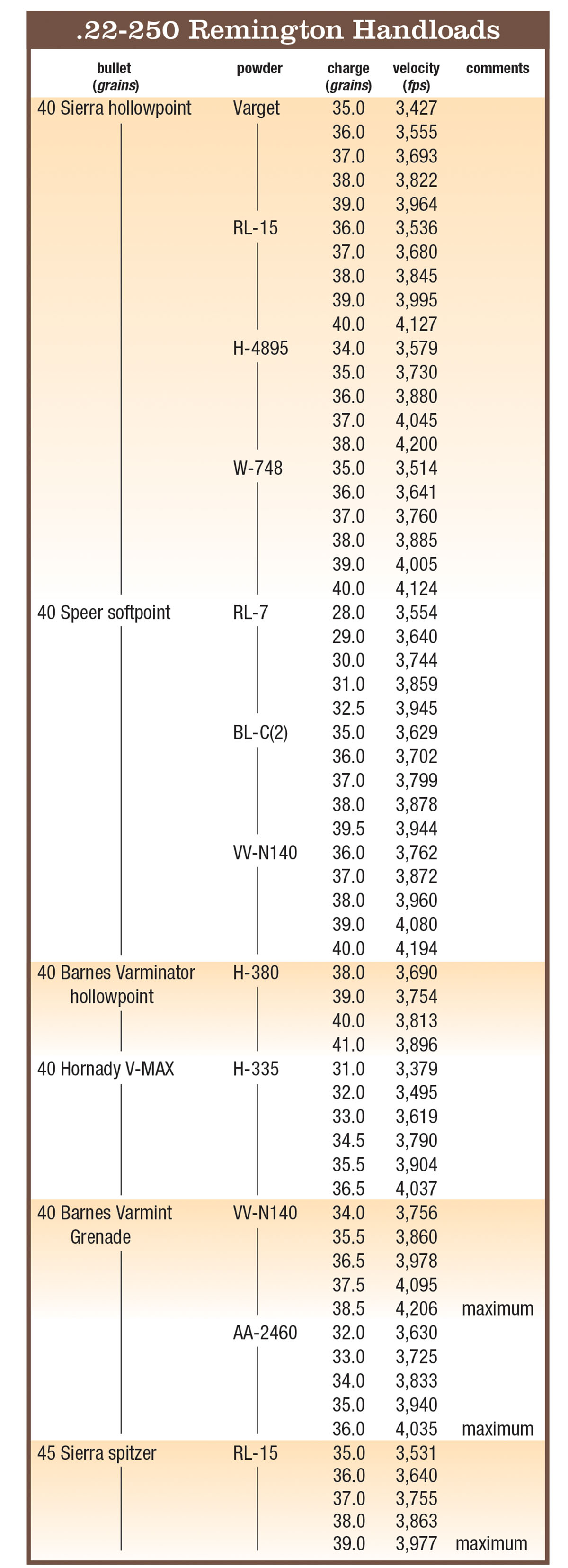

A coyote was spotted on the opposite side of the canyon, so we quickly eased under a tree for cover, sat down and began sounding the predator call. Within a few minutes, “Wiley” came running full speed toward us, but due to the brush and trees, we could only catch brief glimpses. Nonetheless, through the Leupold binocular the eagerness for an easy meal could be seen as he approached. The glass was set aside and the safety pushed forward on the Weatherby Mark V rifle. When the coyote appeared, the crosshairs of the Leupold scope were placed on his shoulder, the rifle swung and the trigger squeezed. The end came instantly from the 50-grain, .22-250 Remington bullet.

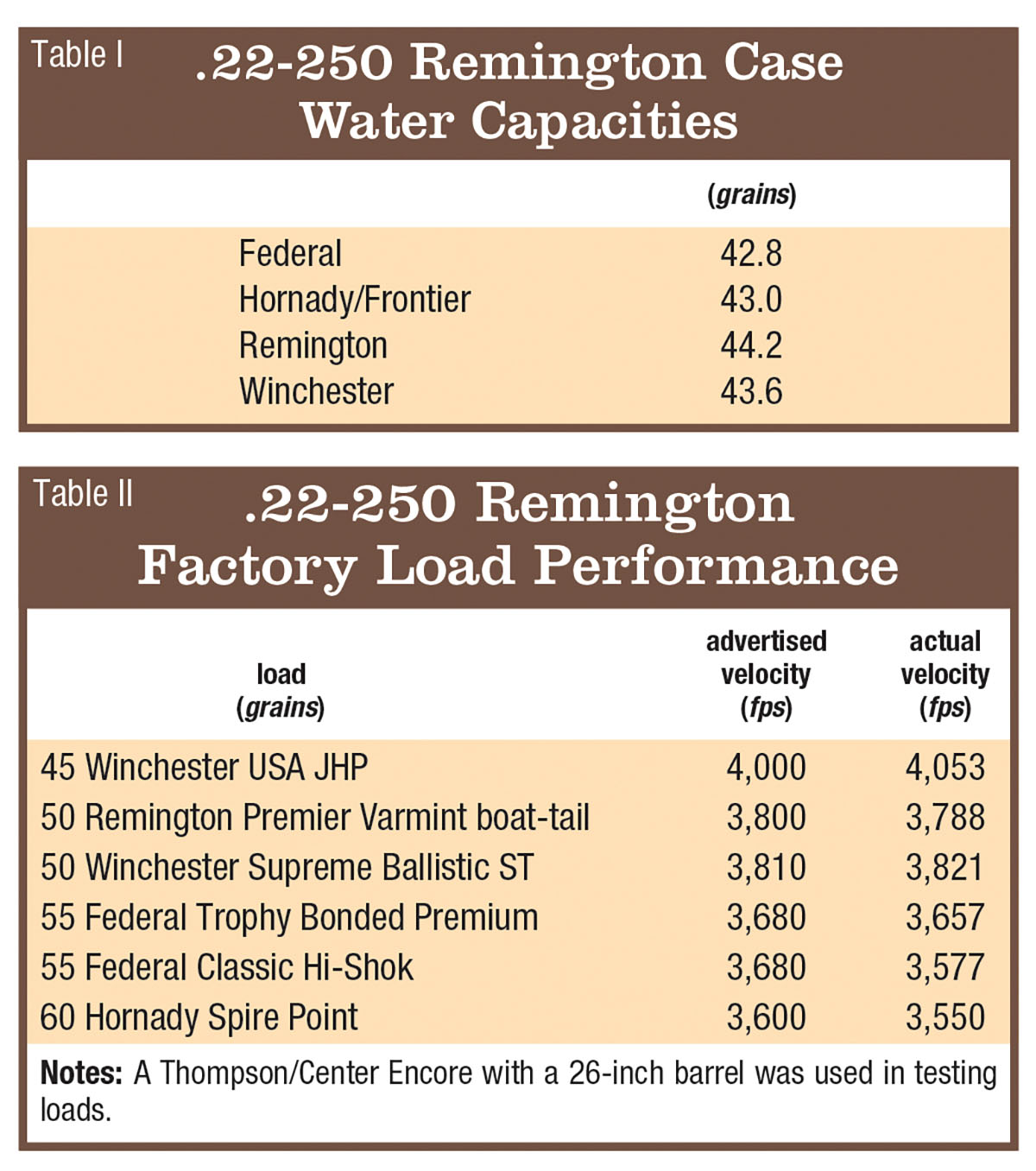

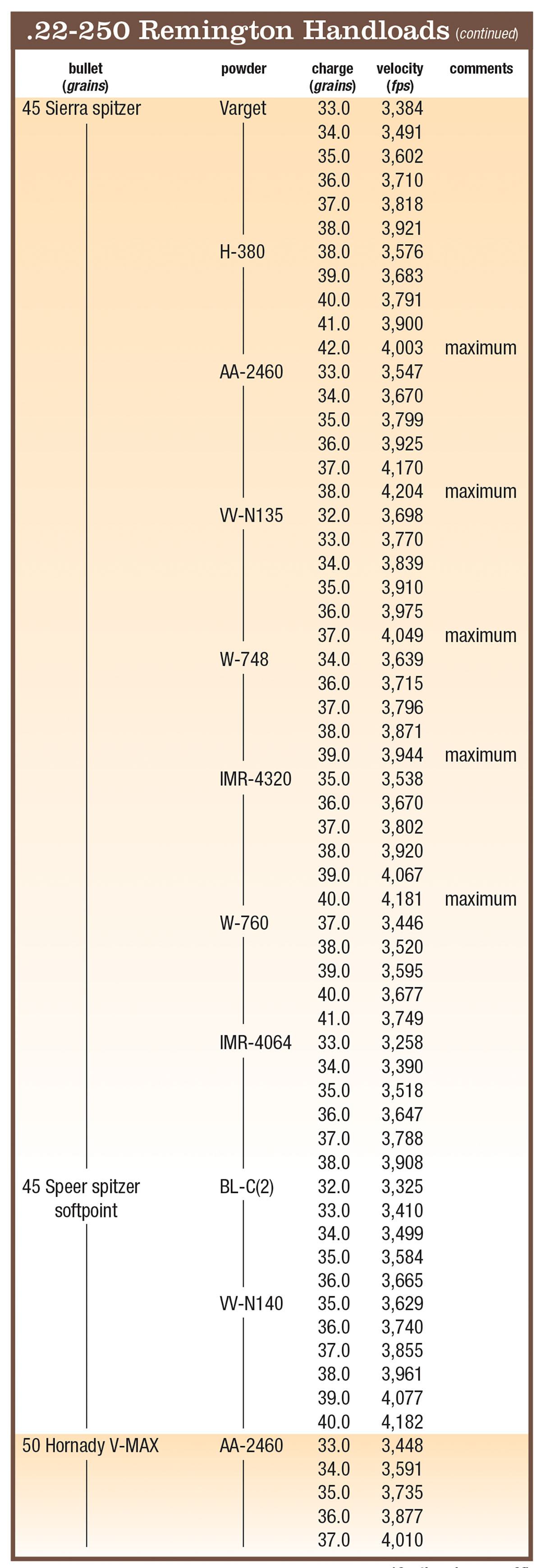

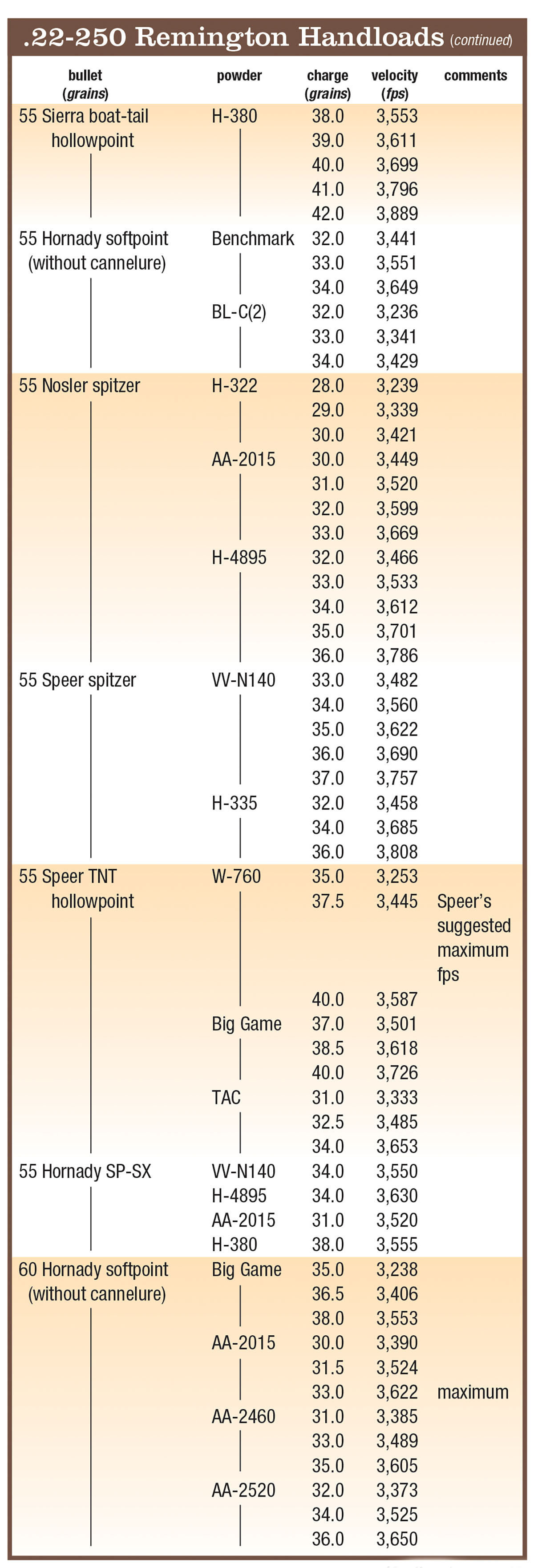

Most rifles – including those from Remington, Winchester, Savage, Ruger, Browning, Weatherby and others – feature a one-in-14-inch twist. Considering the velocities obtainable with this cartridge, it has no problem stabilizing bullets up to 60 grains. Some guns will stabilize the 64-grain Winchester Power-Point and the Speer 70-grain semispitzer, but certainly not all. For these reasons, load data for heavier than 60 grains was omitted in the accompanying tables. (If there are enough requests, I would gladly present data for heavier bullets.)

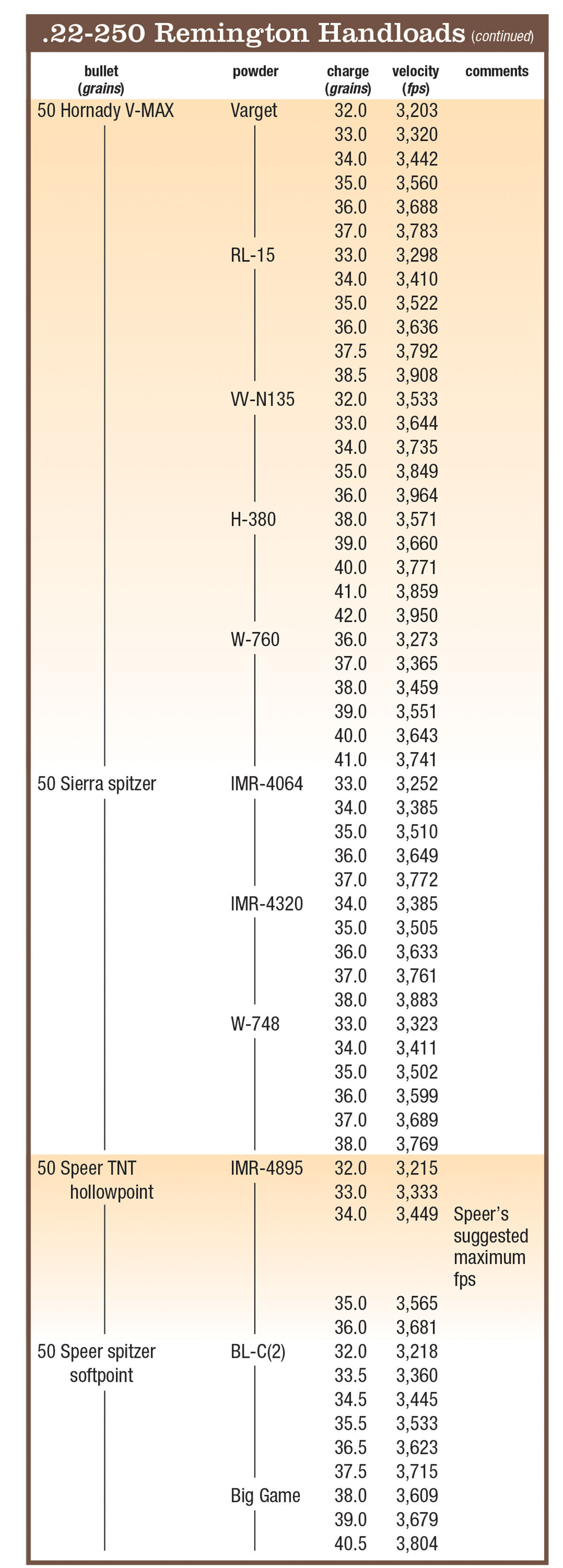

I have had some experience with bullets coming apart during flight and will briefly share some of my observations. When the Speer 50-grain TNT was introduced, I tried it in a number of cartridges and rifles (and I might add that it’s a great varmint bullet). It has come apart during flight at velocities as low as 3,200 fps, but I have also seen it stay together when driven as high as 3,800 fps. Likewise the Sierra 55-grain Blitz has come apart at speeds barely over 3,000 fps, yet can stay together and give excellent results when driven as high as 3,700 fps. In addition to the velocity factor, there are several other factors that seem to come into play, with the most common including pressure, bore condition and rate of twist.

A rough bore can contribute to bullet breakup, while one of higher quality allows the same bullet to run considerably faster without a problem. Each rifle must be considered individually, but if any of the above frangible bullets from Speer, Hornady and Sierra are loaded in the 3,400- to 3,600-fps range from a .22-250 with a 14-inch twist and bore condition is reasonable, there probably won’t be a problem.

For those intending to take deer with the .22-250, there are several viable choices. Hornady offers its 55- and 60-grain Spire Points (without cannelure) that work amazingly well on broadside lung shots, destroying much tissue and usually exiting the off-side. If bone is encountered, a bullet of stiffer construction is suggested. The Speer 55-grain Trophy Bonded Bear Claw will zip right through deer on broadside shots, giving 27 inches of penetration on a Texas whitetail. Another good deer bullet is the Nosler 60-grain Partition, which I have used many times. The Barnes 53-grain, Triple-Shock X-Bullet kills as though it were something larger and is a top choice.

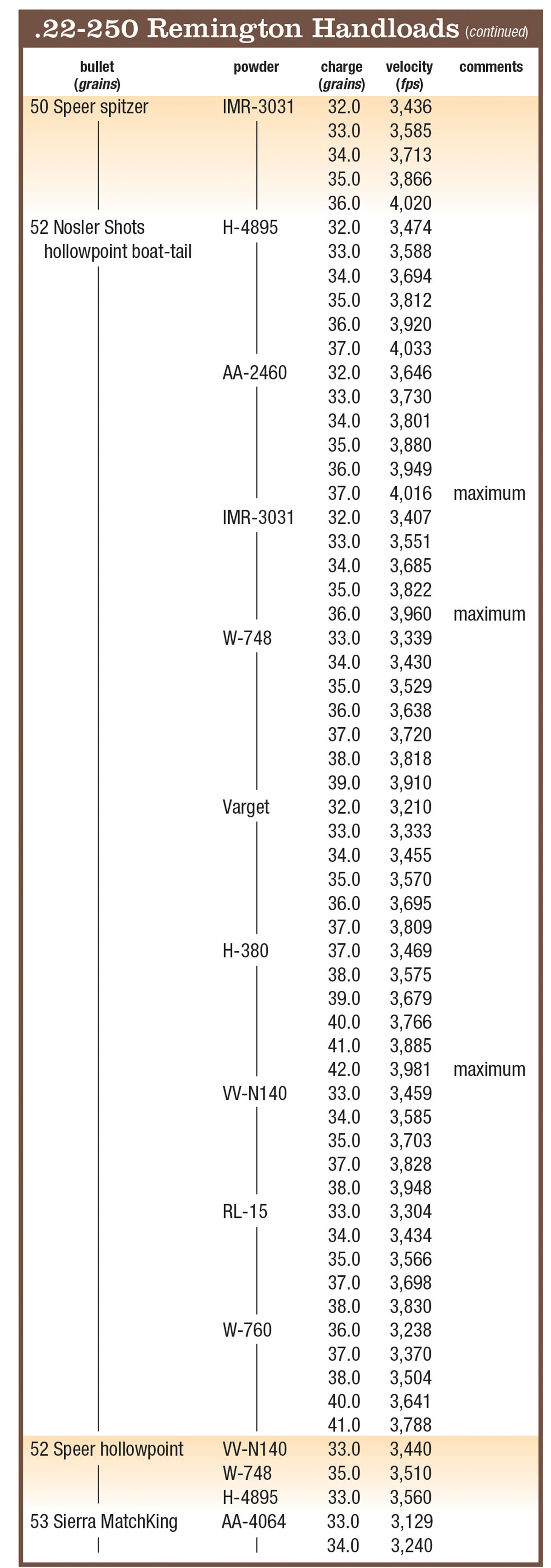

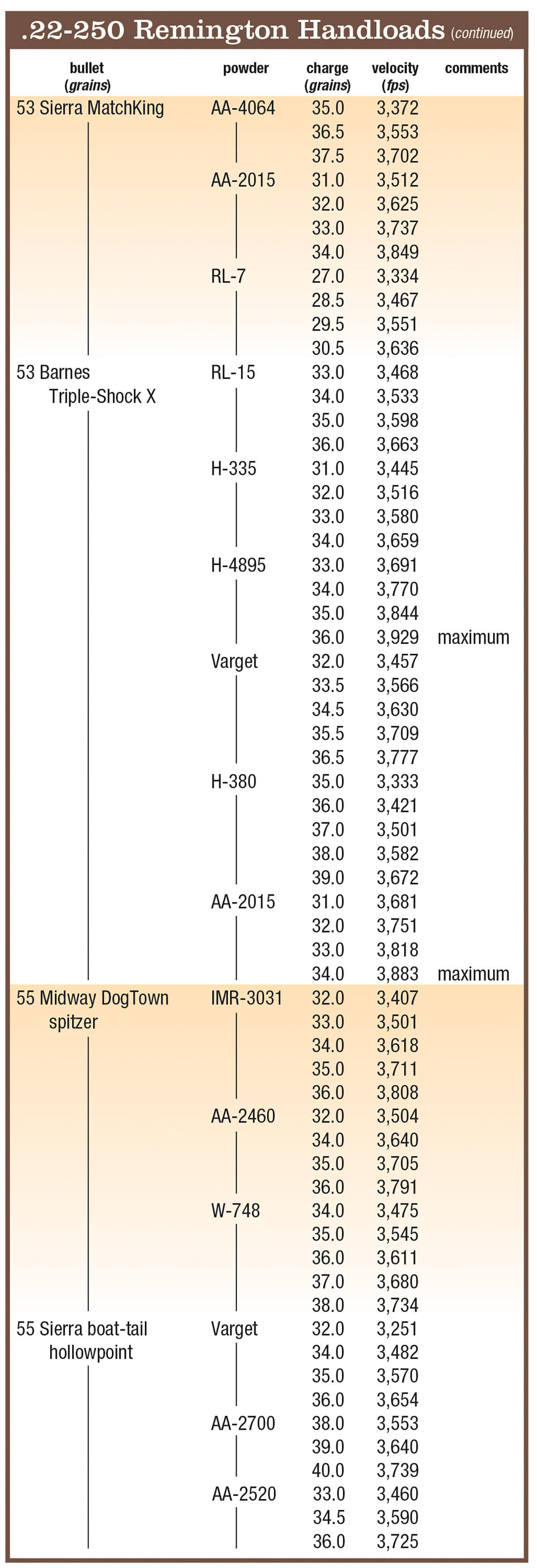

Since its introduction there have always been a number of suitable powders for handloading the .22-250, but today there are many great ones. In selecting the powders that would be used to develop the accompanying data, many had to be eliminated simply because there were far too many to shoot all the potential data in a single article. So the list was cut down to include only 25 powders! It cannot be emphasized enough that we now have powders that make this cartridge better than ever, producing low extreme spreads and high velocities.

Many of the older powders of cylindrical (or stick) shape such as IMR-4064 and IMR-3031 have been used for handloading the .22-250 with generally good results. Back in the 1970s and 80s, I used them both regularly, but they often bridged or hung up in the neck, which slowed the handloading process when throwing charges from a powder measure and posed a potential problem when loading from a progressive press. And their “thrown” weights varied enough that extreme spreads were greater than desired unless each powder charge was weighed. (In spite of these issues, both of the above powders were included in the accompanying data, because they are still widely used and perform well.)

With many of the newer powders, charges can be thrown with remarkable weight consistency and drop through the .22-caliber neck easily. Each of the Ball (aka, spherical) powders used herein could be thrown from a powder measure with con- sistent weights and dropped into the .22-caliber neck without the slightest hesitation. This is especially handy for those who load on a progressive press or load large quantities of ammunition in preparation for a varmint shoot and want to throw charges to speed the process.

While shooting the accompanying load data, it was observed that often the best accuracy and lowest extreme spreads came with loads that fell into the medium to upper pressure range. For example driving the Nosler 52-grain hollowpoint boat-tail with 32.0 grains of Accurate Arms 2460 produced 3,646 fps for a five- shot string and had an extreme spread of 99 fps. As the powder charge was increased, the extreme spread was reduced. Using 35.0 grains produced 3,880 fps, and the spread was 36 fps, while 37.0 grains achieved 4,016 fps and displayed an extreme spread of 19 fps.

In spite of most loading manuals suggesting to start with data that is 5 to 10 percent below max-- imum listed charges, it has been my observation that many handloaders start with maximum charges. Having owned a number of .22-250s over the past 30 years and developing many handloads, I would suggest not starting with maximum charges. Chamber, throat, bore size, cases, primers and other factors can affect pressures, which seem magnified in small-caliber, high-pressure cartridges, such as the .22-250. In studying the accompanying data, increasing a load by just one grain of powder often bumped velocity by 100 to 150 fps and clearly pressures jumped as well. Proceed with caution and check cases for signs of excess or high pressure before attempting the maximum powder charges listed in the accompanying data.

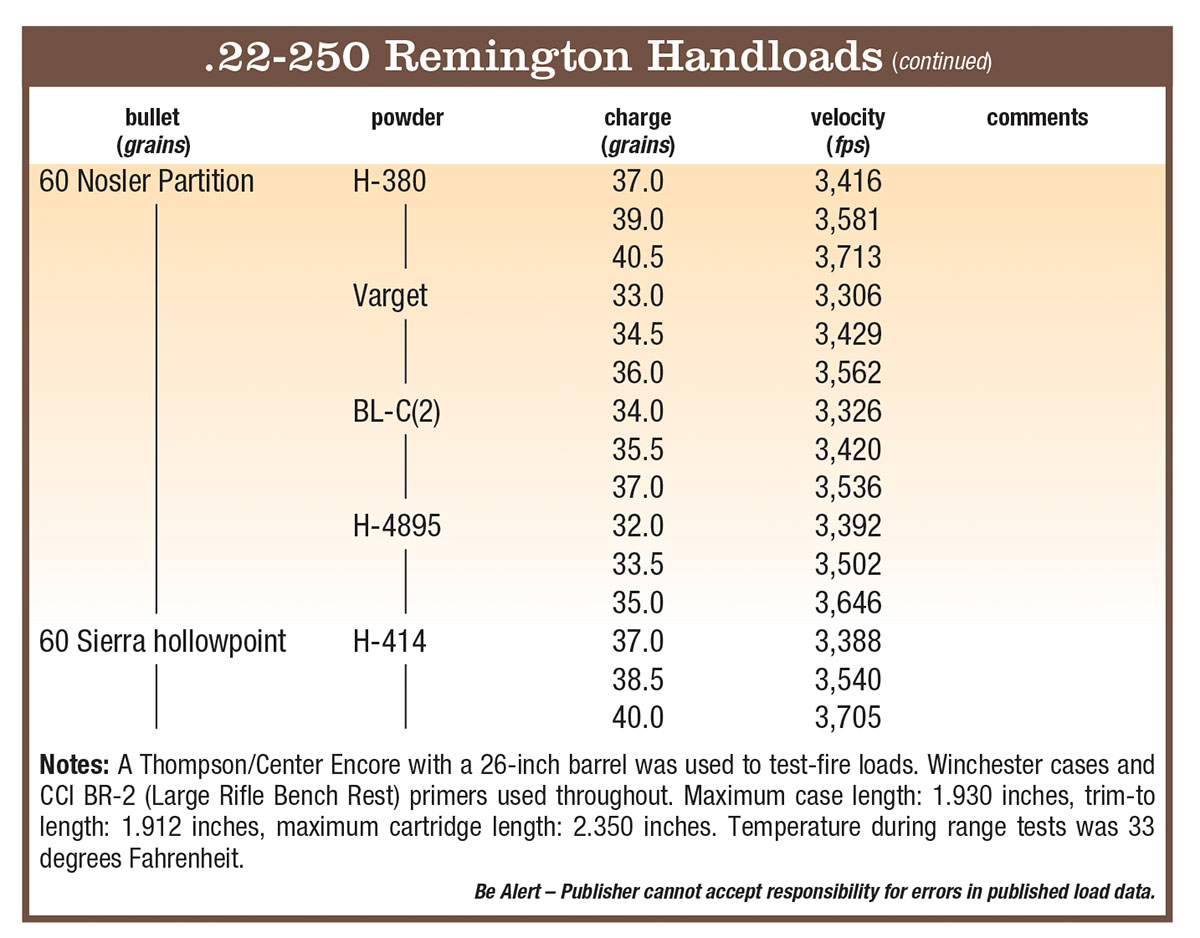

Some .22-250 Remington data has been published that contains Large Rifle Magnum primers, but it has been my experience that no powders used herein required a Magnum primer to obtain reliable ignition in a case of this capacity. To assist in uniformity, CCI BR-2 Large Rifle Bench Rest primers were used exclusively.

For this handloading project, a Thompson/Center Encore rifle was chosen that was fitted with a 26-inch varmint barrel. This gun is easily a sub-MOA performer and has been used on several varmint shoots. Furthermore the easy access to the barrel’s breech was appreciated, wherein a tube (attached to a several-gallon water container) could be inserted into the chamber and water poured down the bore to quickly cool the barrel between strings of shots. (Naturally chamber and bore were swab-bed dry before proceeding with the next set of loads.) The Encore also functioned flawlessly through the extensive shooting sessions.

A Weaver Grand Slam 6-20x scope was installed that features an adjustable objective, 1⁄4 MOA click adjustments with Micro-Trac, a proven four-point adjustment system and fully multicoated lenses. Over the years I have used a number of Grand Slam scopes and found them to be reliable and a good value.

The most impressive aspect in assembling and firing the accompanying .22-250 data was the broad base of uniform accuracy. Certainly some of this can be attributed to the Thompson/Center Encore rifle, as it regularly placed four shots under an inch, but any reasonable load seemed to give consistent velocities and is an indication of just how easy it is to reload this cartridge.

Naming “the best” loads is virtually impossible, as many gave excellent results, and there are literally dozens of loads in the data tables that I would happily choose to employ in the field on long-distance varmints, coyotes or deer. With more than 3,000 cases loaded and several rifles sighted in, I am ready for a great spring and summer of varmint shooting with the modern-day classic .22-250 Remington.