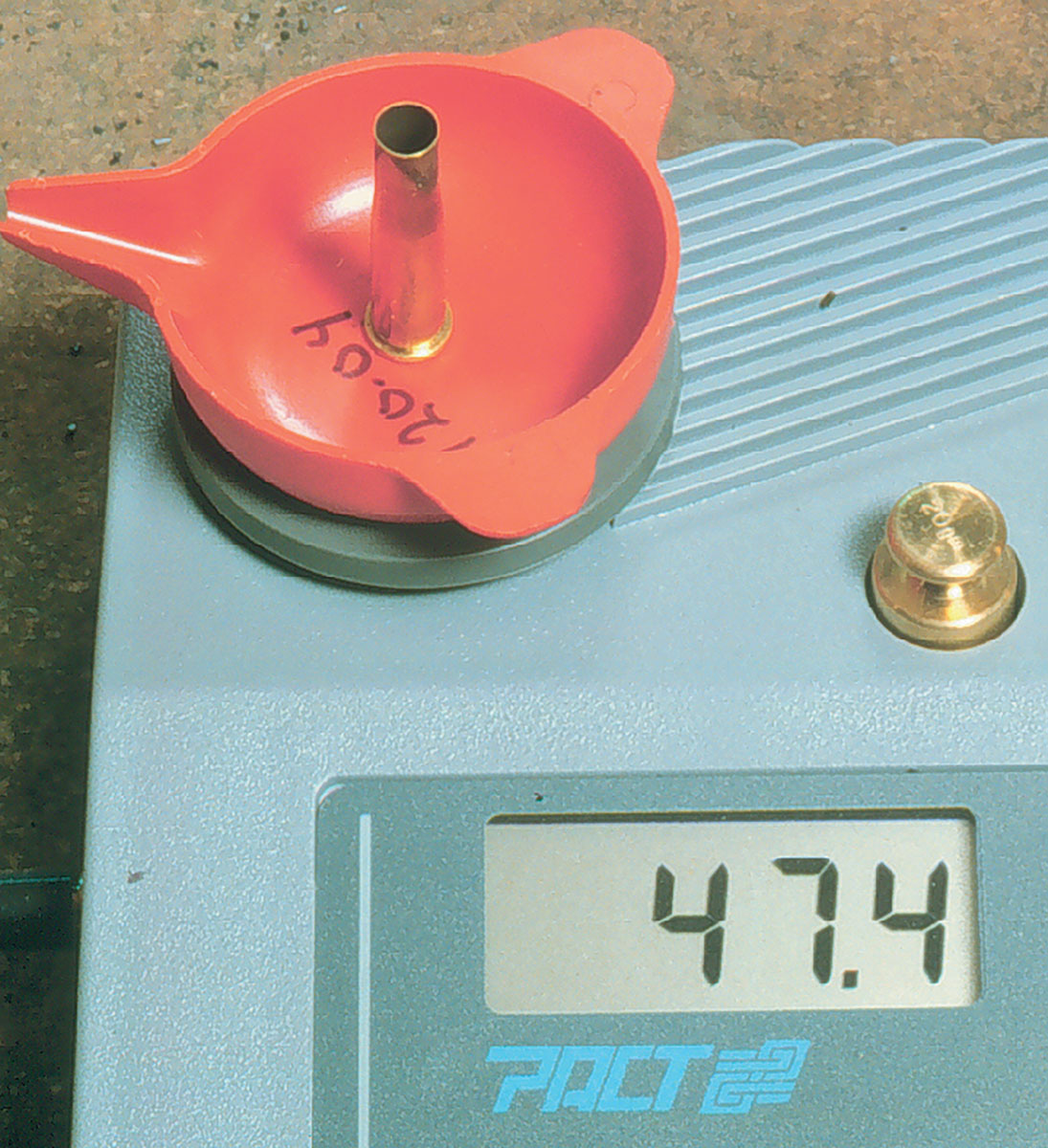

22 Hornet

Top Loads for the Littlest 22 Centerfire

feature By: Ross Seyfried | April, 14

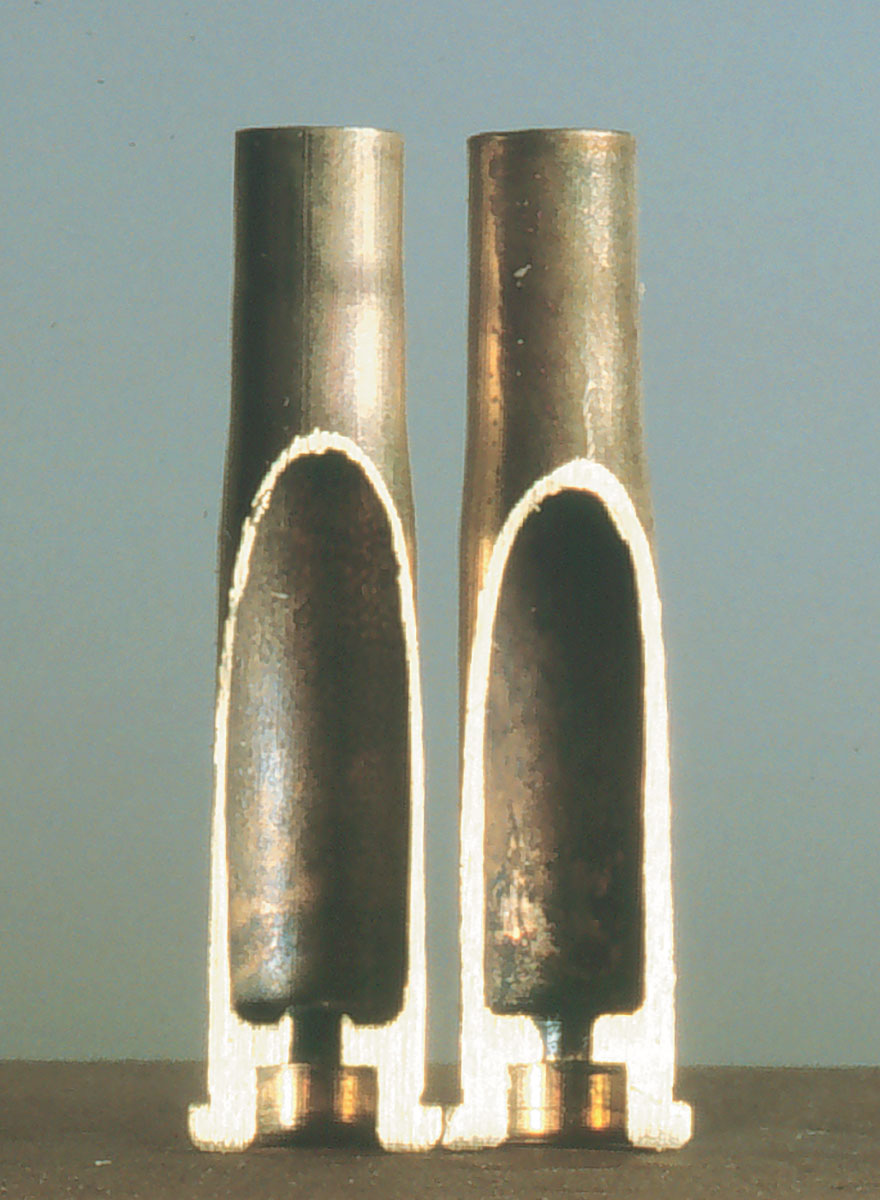

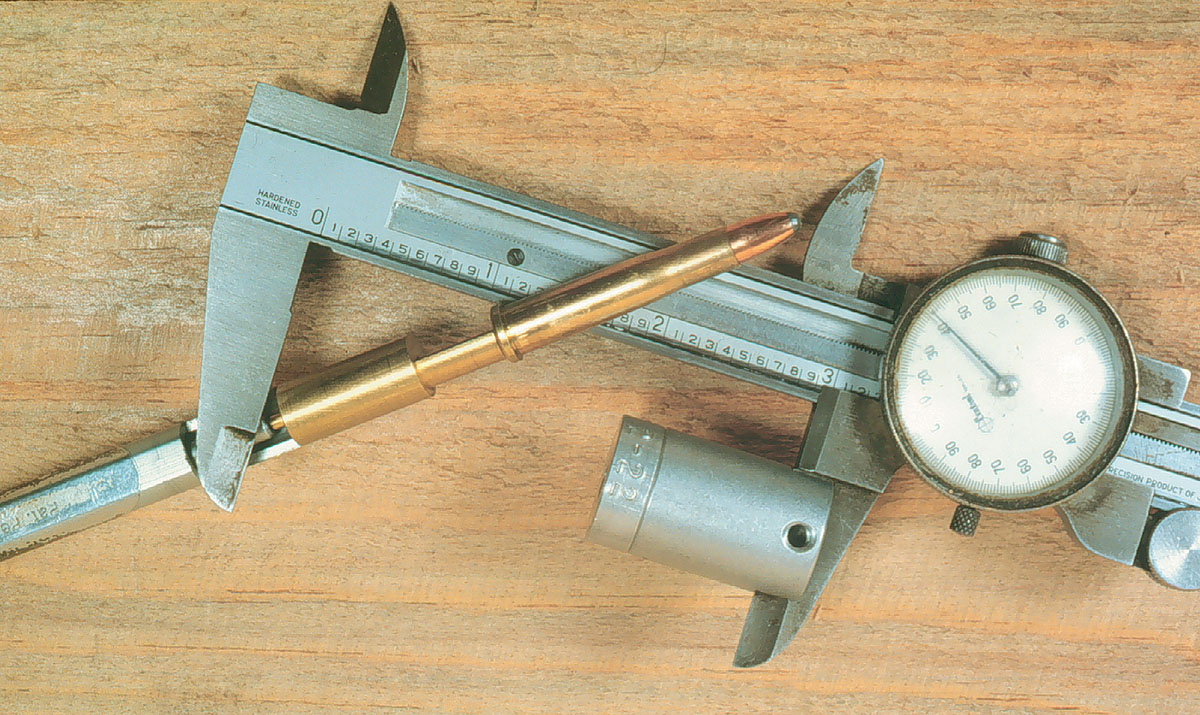

On the other hand, many accurate rifles will be inaccurate, even with handloads that would appear to be very good ones. Here is where we begin to see the extremely fastidious nature of the little shell. Essentially it is all taper. There is little about the shape of a Hornet case that causes it to align perfectly in the chamber. Because it is short, just like the short sight radius on a snub-gun, any degree of misalignment is magnified. Therefore we begin by looking for ways to cause the cartridges to be pointing straight down the barrel before the primer lights.

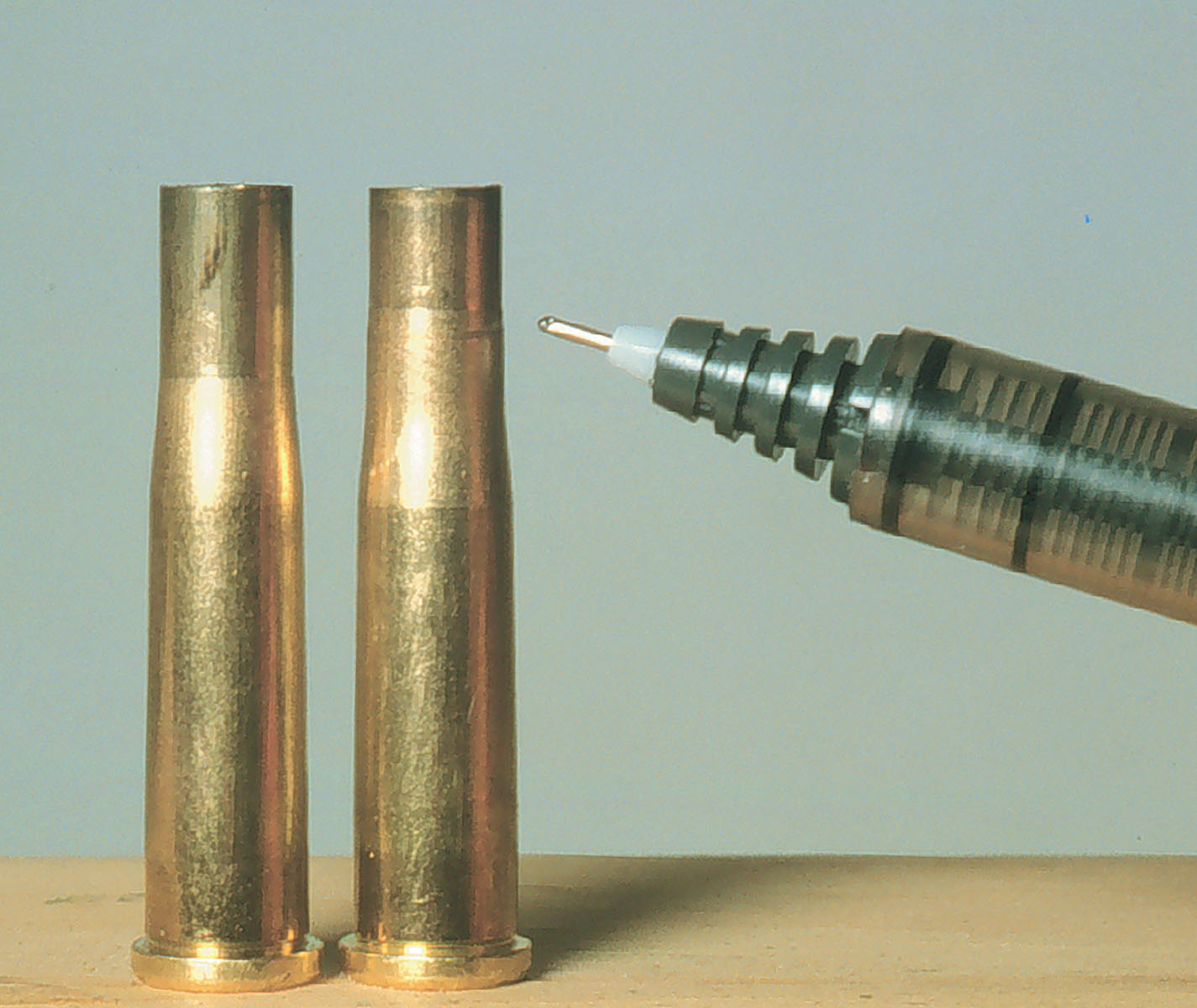

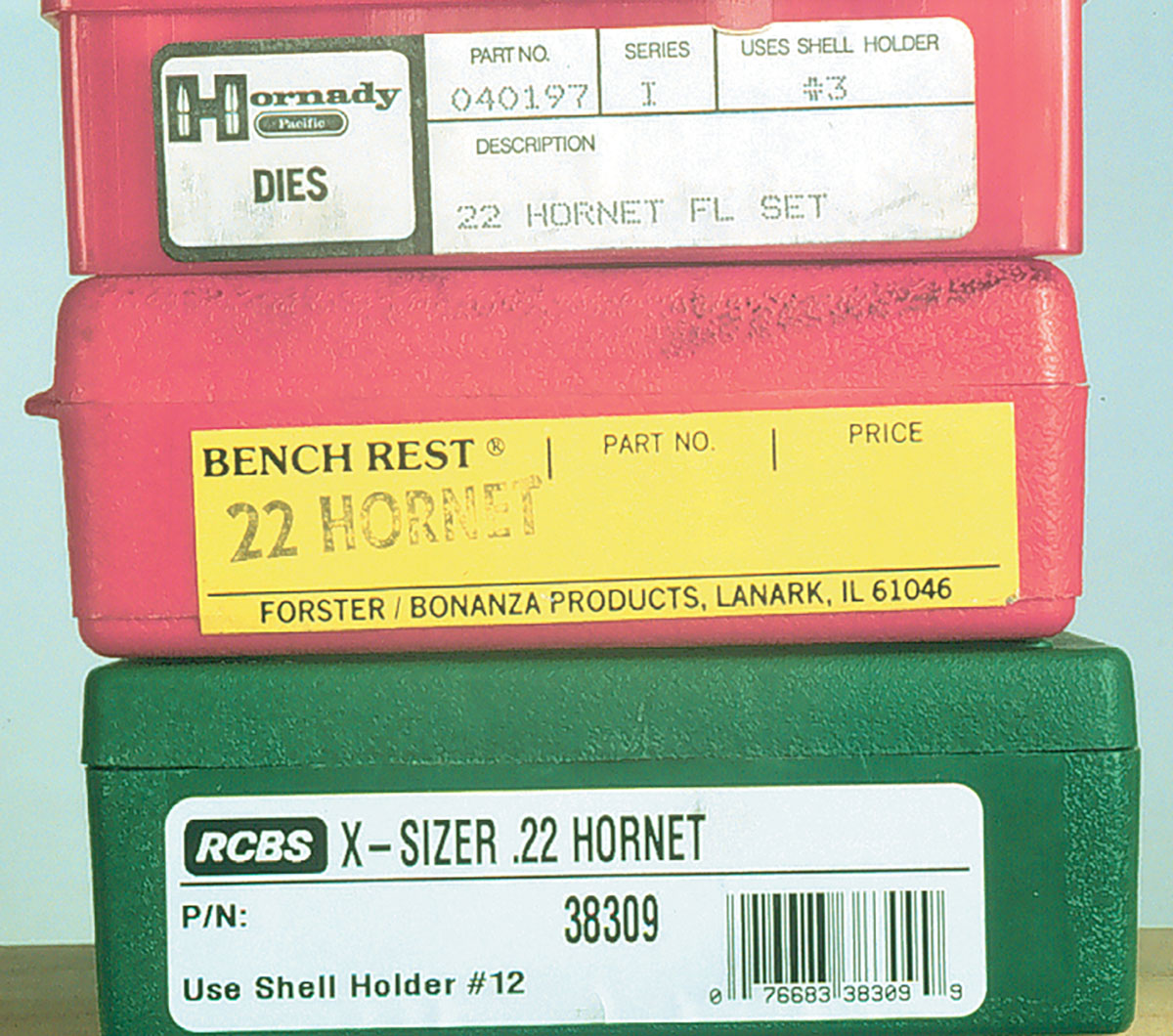

Here we can return to good, basic handloading practices. First, you should use cases that have been fired in the rifle where the loads will be used. This ensures that cases fit the chamber to absolute perfection. Then, we will neck size only. You can use special neck-size-only dies, or do as I do and run a normal full-length sizer that is backed well away from the shellholder. Sizing about .200 inch of the case neck is usually plenty. All you want to do is reduce enough of the neck to hold the bullet securely.

This neck sizing does two things. First, it leaves us with a case that is held in the center of the chamber by that portion of neck that has been left unsized. This also leaves the case shoulder, tapered as it may be, in a position to touch the front of the chamber. Now it headspaces on this shoulder, not on the uneven rim. Further, this sloping

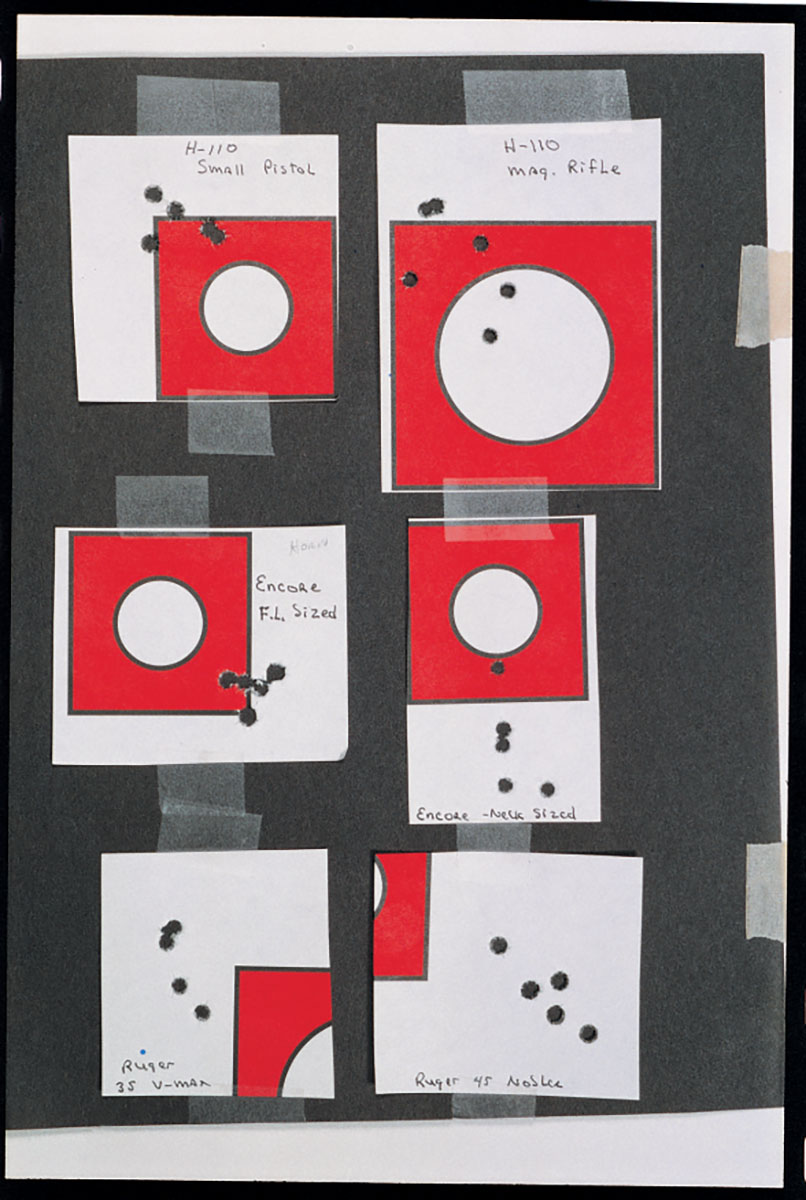

Before we leave the subject of cases, be sure not to overlook case brand. Hornet cases vary widely from maker to maker. There is no good or bad about this, only different. The average case weights I find are as follows: Remington-Peters – 47.4; Frontier – 51.8; and Winchester-Western – 53.5 grains. When you consider that most loads use only 10 grains of powder, even a slight variation in case capacity can make a big difference. Therefore, if you have different case brands, be sure to keep them sorted. Also, Hornet cases will grow as you use them, and often grow at different rates. It is a good idea to keep them trimmed to the same length. The little Hornet is about details, little details.

There is no better way to achieve this than with a Stoney Point OAL gauge (combined with a special Hornet adapter). This clever tool allows you to test various bullets in your chamber and then measure the length from the head to the ogive. This length varies surprisingly, even with bullets of the same weight. The shape and design of the ogive have a lot to do with where the bullet actually hits the rifling.

The best plan is to make a few cartridges with the bullets seated .010 inch short of touching. Test this accuracy, then try some that are .020 inch away, followed by some that have “zero” clearance. With these three batches the rifle is almost sure to tell you what it likes. One glitch is that most of the detachable-clip magazines severely limit overall cartridge length. The Ruger is about the longest at 1.820 inches, while the CZ/BRNO magnums are shorter at 1.730 inches.

What this means is you may not be able to touch the lands with cartridges that will fit in the magazines. It is possible to shorten the plastic “filler” that is inside the BRNO clip, allowing it to take longer rounds. I have done this on my old Fox, because it loves ammunition that is wedged into the lands. Others are not so demanding, while the single shots, like the T/C Encore, will accept any cartridge length.

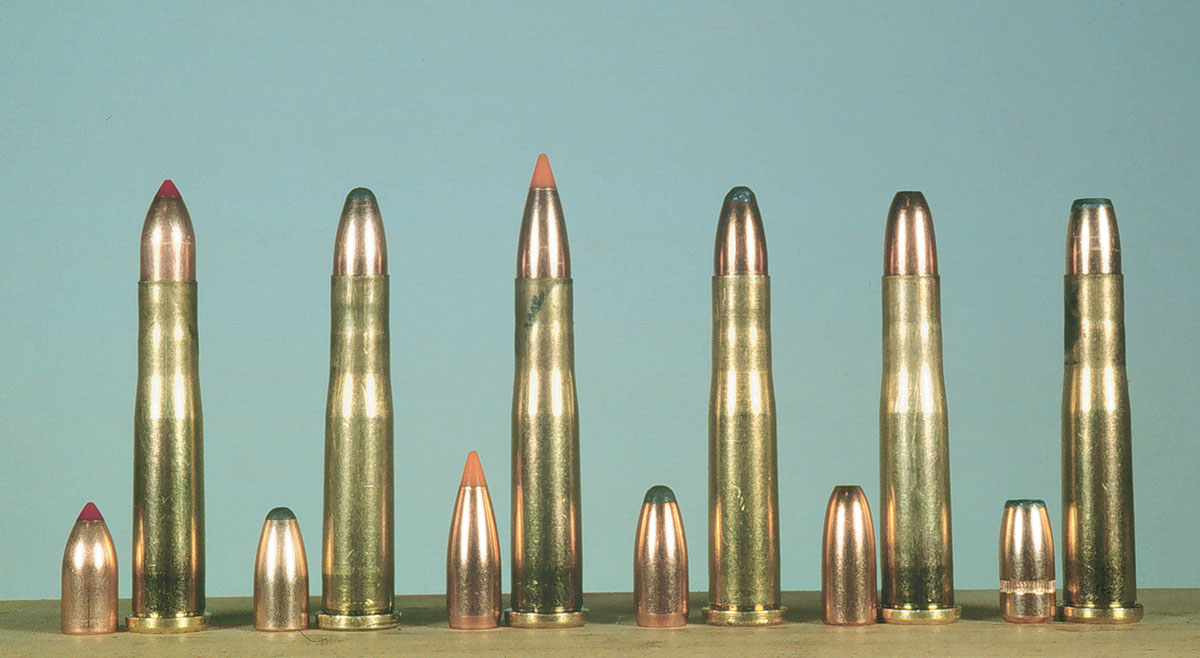

Now there are many of the light .224-inch bullets that work well in Hornets. Speer has 40 and 45 grainers, as well as a flatpoint for the 218 Bee; Nosler offers 40-grain Ballistic Tips, and Hornady has the 40-grain V-MAX as well as the delightful little 35-grain V-MAX that is in its factory ammunition. You can also buy the Winchester bullet as a component. In addition to the bullet variety being a serious factor in accuracy, as you will see in the load tables, different bullets can also give you a fine variety of terminal performance. While most loading manuals will give you data for 50- and 55-grain bullets in the Hornet, I rarely find these long bullets offer anything especially desirable.

Most of the dedicated Hornet bullets will have quite thin jackets and are reasonably explosive on impact. The Hornady 35-grain V-MAX is absolutely spectacular, offering almost big-gun ker-splat out of the little case. At the other end of the spectrum are the light bullets designed to stand up to extreme speed from a 22-250 Remington or 220 Swift. These “4,000-fps” bullets have pretty tough jackets and may actually act in a controlled-expansion manner, at the relatively slow Hornet speeds. With some experimentation you may find that an ultra-high speed bullet may expand just a little at 2,500 fps, making it perfect for turkeys, rabbits or squirrels. My favorite all-around Hornet bullet is the last surviving, old-fashioned Nosler Solid Base. This is the 45-grain Hornet with a standard lead tip instead of the plastic nose. It is usually very accurate, quite violent on impact but with enough integrity to plow through plenty of coyote or even the skulls of larger beasts.

There is also a very interesting Hornet powder on the market. As it turns out, it may also be the best magnum pistol powder. This is Hodgdon Lil’Gun. It was designed for .410 shotshells and has quickly adapted itself to big revolvers and the little rifle. It is especially happy with 45-grain bullets, at times beating H-110 in the speed department, while reducing pressure. As I mentioned earlier, powder weight is critical in the little case. While in most rifles I usually worry in full-grain increments, or at worst .5 grain the Hornet will notice .10-grain changes. Using H-110 as an example, .10 grain can add 50 to 100 fps, at near maximum loads. So, do not be afraid to tweak your powder measure just a little in experiments, keeping in mind that few powder scales will reliably detect .10 grain.

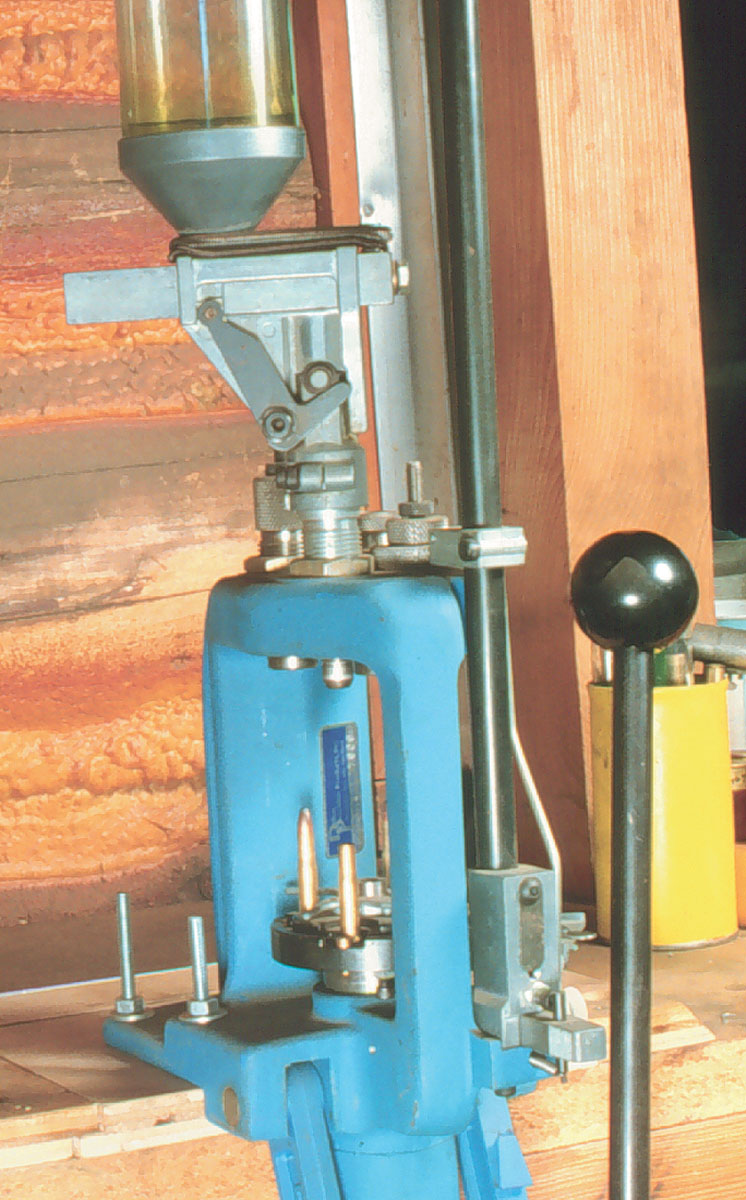

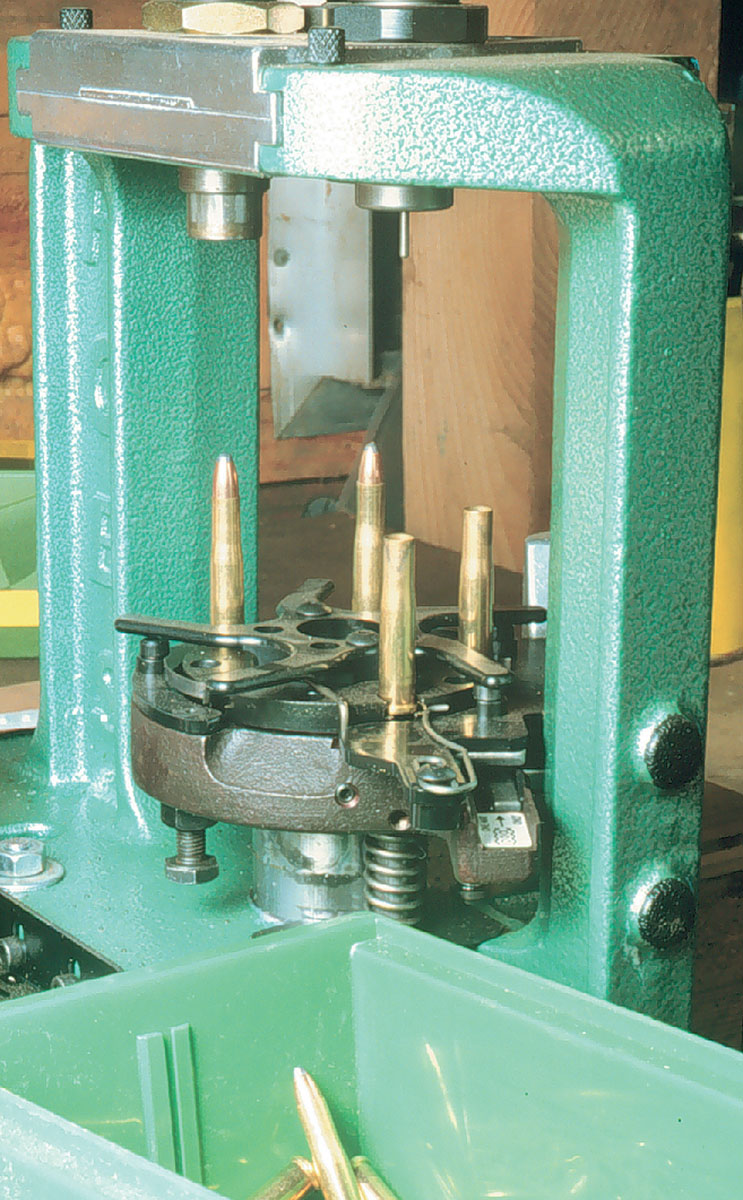

When I load shells for Hornets, I have two criteria: accuracy and lots of them. To that end, in addition to neck sizing, I like the floating-chamber “benchrest” seating dies. Mine are from Forster/Bonanza. Dies like this get the bullet and case in a die before it starts to push the bullet into the case. The result is often a straighter round.

When we talk about lots of shells, I mean pockets full that come off a progressive reloading press. A Dillon 550 has been my standby for a long time. With properly adjusted dies and ball powder, this machine will produce ammunition that will shoot right up to the rifle’s ability. Another tool on my bench is the RCBS 2000 Progressive machine. It is very similar to the Dillon with a different style powder measure and the magic RCBS APS priming system. Both these machines give you a finished shell at each pull of the handle, or something like 500 or 600 an hour. By using Dillon or Midway spray case lube, it is possible to turn out ammunition almost as fast as the average Hornet shooter will use it.

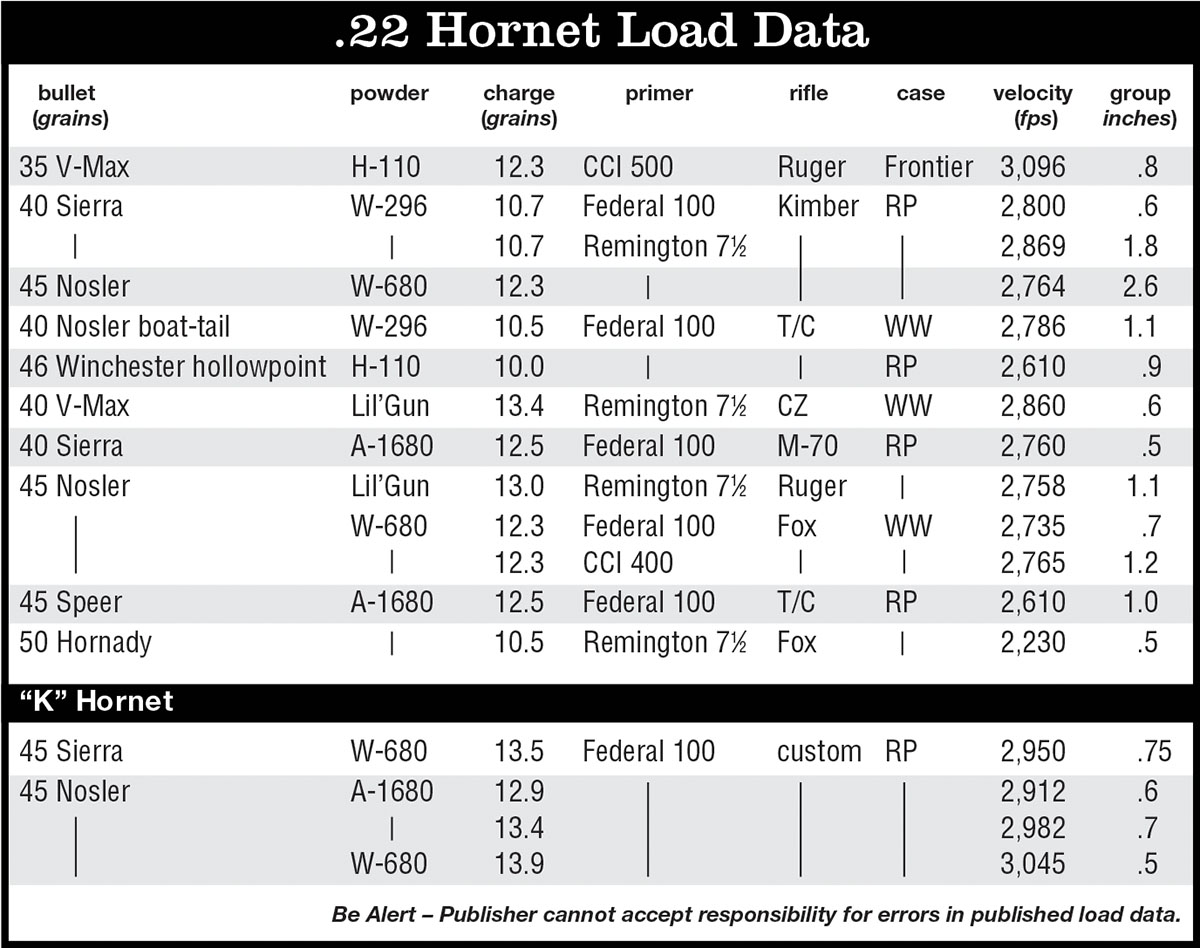

With an overview of some of the ways to make Hornets happy, let’s look at the three rifles to see how they responded to some coddled ammunition. First, as almost expected, the Ruger shot groups with well-fitted reloads that were almost identical to the factory shells. This is because of some problems with the factory bedding, especially in the forend area. The stringing was more defined; that is, it almost cut slices in the paper. This showed that the loads were indeed more accurate, but it was unable to put them in a tiny group.

My T/C Encore proved to be a bit of a head-scratcher. During the shooting it started to do some strange things, not the least of which was double grouping, shooting two small groups about 3⁄4-inch apart with each string. I traced this to a bit of a bedding problem in the forearm. Once this was straightened out, it began to shoot round, “honest” groups.

As the search for the perfect load went forward, a trend began to emerge. The tighter the ammunition was in the Encore, the more it wanted to string vertically. With the cases barely sized and the bullets seated in the rifling it would not equal its fine performance with factory loads. Okay, I thought, if it doesn’t like the snug treatment, let’s see what happens if we full-length size the cases and give the bullets just a little clearance. Bingo, little groups.

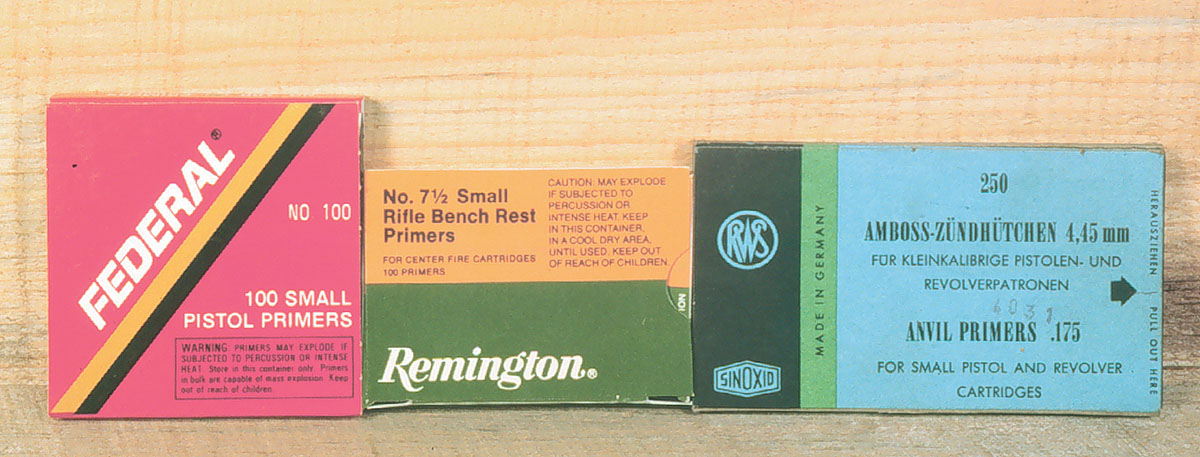

A few other rifles and their preferences are interesting. One of the toughest I have ever faced was a full-length Mannlicher-stocked Kimber. Now, from a pure accuracy standpoint, the full-length forend wood is a bad idea. I fussed with the bedding until it seemed happy, then I went after a load. This is a real one-man dog. It only likes 40-grain Sierra bullets and W-296 powder. Where it averages less than 3⁄4 inch with this load, twice that is about the best it will do with other apparently fine ammunition. This was one that went from 11⁄2-inch groups down to as little as 1⁄2 inch with exactly the same load, except Small Pistol primers were used instead of Remington No. 71⁄2 Small Rifle primers.

The old Model 70 likes the 40-grain Sierra bullet, but this one wants a big dose of W-680 powder instead of the faster W-296. With this combination, the old, huge rifle often gives us a 3⁄4-inch group and sometimes much less.

As ugly ducklings go, the BRNO Fox wins. It is rough and horrible with its poor imitation of a Weatherby stock, but the wretch will shoot. It rarely goes over 11⁄4 inches with anything and really likes the 45-grain Nosler Solid Base and W-680 or Lil’Gun powder.

There is one last part of the Hornet story – the improved “K” Hornet. The improved version with almost no body taper, a sharp shoulder and short neck all of a sudden becomes an almost perfect cartridge. Everything that is wrong with the regular round is instantly erased. Not only does the improved version give us more velocity, at times 200 fps more, it usually just begs to shoot.

Once upon a time I had a Ruger No. 1 Hornet. Even with forend modifications it was mediocre, rarely breaking an inch. A quick stab with a “K” reamer, with no other changes, turned it into a super-accurate rifle. I also have a very exotic and wonderful “K.” This one began as a Kimber Model 84 action that was welded and reworked into a Hornet. It takes seven rounds from the top, just like the Model 70, eliminating the annoying clips. Then it was stocked in a screaming piece of California Claro walnut by Don Allen. The end result was an all-day, everyday, .5-inch rifle that is just about as sleek as a bolt rifle can be.

A nightmare or a handloader’s dream? The Hornet, like so much in life, is all about perspective. If you like easy out-of-the box accuracy, a 222 Remington probably suits you best. On the other hand, if you like to put some effort into fine-tuned handloads and see real results, the Hornet is for you. Hornets are by far my favorite “little” rifles. They might be yours too.