Cheap Shots!

Cast bullets provide inexpensive varmint loads.

feature By: John Haviland | April, 14

Bullet Considerations

Casting .22-caliber bullets may not be worth the toil. Gas-checked 22 bullets you cast yourself cost about $2 per 100. However, various reloading supply catalogs sell plain-jane jacketed .22-caliber bullets for $5 per 100. So the $3 you save casting your own comes at the expense of your time spent making the bullets. But reloading is a hobby, and satisfaction comes from the busy work.

Time spent casting .24- and .25-caliber bullets is well worth the effort. Every time a bullet drops from one of these moulds, I save nearly a dime over a store-bought jacketed bullet. (However, viewed from a fiscally responsible position, I’ve never saved a dime reloading or casting bullets. The money has just been redirected toward new moulds, powders and bullets.)

For gopher (and target) shooting out to 100 yards, .22-, .24- and .25-caliber bullets are fine with a muzzle velocity of 1,600 fps. At 60 to 65 yards, these bullets hit 1.3 to 1.5 inches high when sighted in at 100 yards. Once they reach 130 yards, though, they have dropped 3.0 inches and really plunge after that. Higher velocities of 2,000 to 2,300 fps flatten the midrange rise to less than .5 inch and drop at 150 yards to about 3.0 inches.

I took an easier approach and cast all the bullets listed in the load tables out of harder Linotype. To make sure Linotype was hard enough to withstand these higher velocities, I fired 60 bullets with a muzzle velocity of 2,100 fps from a Kimber Varmint 22-250 Remington. A three-shot group fired after all those rounds measured just over one inch at 100 yards. A Hawkeye borescope revealed only a bit of lead had accumulated in the leade and one short streak on the leading edge of one rifling land. The rest of the bore was clean except for powder fouling and a hint of blue the length of the bore from the Thompson blue lube. Most of the 60 bullets were RCBS-55-SPs that had only one lubricating groove. A patch soaked with Bore Tech Bore Solvent followed by 10 brush strokes then three patches cleaned the bore.

Bullet Designs

The Lyman 225646 Super Silhouette 55-grain bullet is one such bullet with a short body and long forward section that is supposed to ride on the lands. This bullet also features an additional lubricating groove around a nose that tapers from throat diameter to land diameter to align the bullet with the bore. A bullet with all these features should be the answer to accuracy.

The RCBS-55-SP bullet also has a nose that is supposed to ride on the lands. It provided a bit more contact with the bore over its length than the Lyman bullet, and the result was several groups under one inch in the 223 and 22-250 Remingtons.

The NEI 45- and 55-grain bullets are designed with a long body of groove diameter. Sixty percent of their length is full diameter body to match groove diameter. The nose of these bullets quickly tapers to a point and doesn’t ride on the lands. This NEI design shot well in the 223 and 22-250 Remingtons.

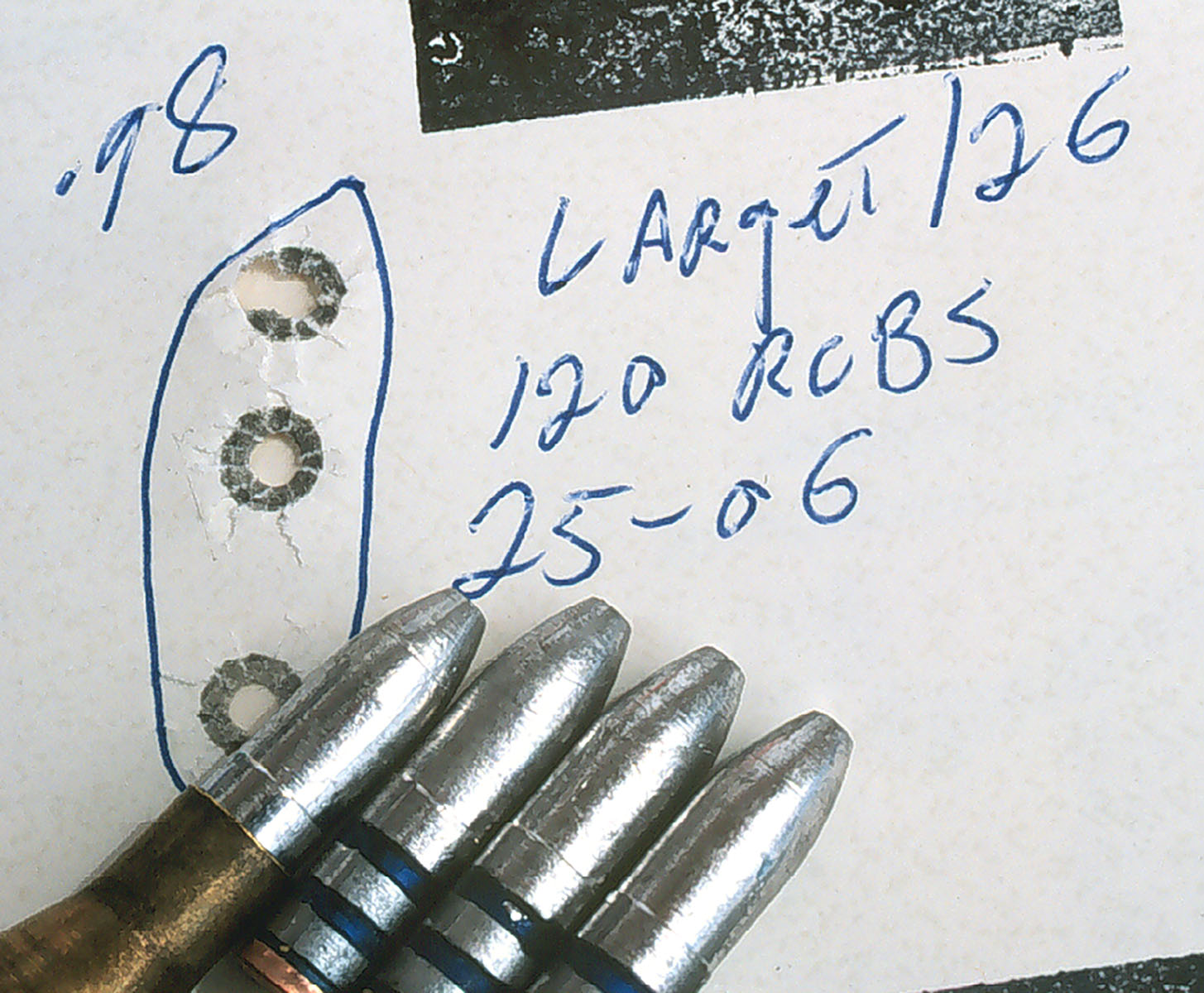

Unfortunately, a steady diet of 75- and 85-grain jacketed bullets at 3,500 fps has pretty well cooked the first 4 inches of the rifling of my Ruger 25-06 Remington, and the rifle’s precision the last few years has gone downhill. The rifle used to group the RCBS-120-SP bullet with Unique, H-4895 and H-4198 into less than 1.5 inches at 100 yards. But alas, of the 15 combinations of powders and bullets listed in the tables, only five grouped tighter than 1.50 inches. However, the rifle still groups Nosler 120-grain Partitions well under one inch with a full load of H-4831.

E.H. Harrison, the technical advisor decades ago to the American Rifleman, wrote in a January 1983 article “Bullet Fit Is the Key to Accuracy” that jacketed bullets are guided by a bore’s grooves, and they shoot well as long as the bottoms of a bore’s grooves remain uneroded. Harrison cited military tests that found groove diameter increased only .0004 inch after firing 20,000 rounds of 7.62 Russian. Group size, however, only doubled from what it had been after firing 14,000 rounds.

So for a bore with worn lands, like my poor 25-06 Remington, a cast bullet with a relatively long body of about two calibers long (like a jacketed bullet) would be best. All three of the .25-caliber bullets listed in the load table had bodies one-half to two-thirds their length. Each one shot a couple of groups that were precise enough to hit a gopher at 150 yards. But compared to the 6mm Remington loads, the 25-06’s worn bore shot rather poorly. Perhaps the time has come to quit procrastinating and have a new 25-06 Remington barrel installed.

Seating Depth

All the bullets listed in the tables were seated so the noses sat snugly against the rifling. That worked well for all the bullets except two. The base of the long body of the NEI 55-grain bullet protruded .147 inch below the case neck. That exposure to powder gas can ruin a bullet’s base and driving bands, but in this case the gas check covers nearly all the exposed base. In the 6mm Remington, the 2.89 inch loaded cartridge length was too long to fit in the Model 600’s magazine. Cartridges measuring 2.80 inches in length fit in the magazine, but I wondered if they would shoot as well. Not to worry, though, because the shorter cartridges grouped a bit tighter. Could it be the 6mm’s relatively long neck, tight fit of the bullet in the throat and the lands kept the bullets in alignment with the bore?

Powders

Relatively fast burning pistol-type powders usually produce good accuracy up to 1,600 fps in .22-, .24- and .25-caliber cartridges. I say usually because Unique produced dismal accuracy in the 25-06 Remington. However, pressures rapidly increase with these powders when velocities are stepped up to 2,000 fps and more. That increased pressure is too much for cast bullets to withstand and accuracy suffers. One exception was Unique in the 223 Remington. This bulky powder filled three-fourths of a 223 case, generated speeds of 2,000 fps and shot great. Seven grains of Unique with the RCBS-55-SP bullet had a velocity spread of zero and grouped the bullets into .59 inch.

At these higher speeds, slower-burning powders like Varget, TAC, Reloder 7, H-4198, XMR-4064 and W-748 burn at nearly half the pressure of pistol powders. Their pressures also rise over a longer period to reduce the slam to a bullet.

The 223 Remington doesn’t burn much of any of these powders with cast bullets. Some amounts were similar to those loaded in the 357 S&W Magnum. So I tried a Small Pistol primer with several powders to find if the primers provided enough flame to ignite these powders and at the same time reduce pressure and turbulence to produce more even speeds. That was the case, at least somewhat, with Unique. Winchester Small Pistol primers had a velocity spread of 55 fps compared to 68 fps for Winchester Small Rifle primers. But as Table I shows, Small Rifle primers produced less velocity spread with other powders and 55-grain bullets in the 223.

In the Field

If only the cost of running my pickup were as inexpensive as these cast bullet loads, I could drive out everyday to shoot gophers. The 223 Remington with a 55-grain bullet and 7 grains of Unique cost 4.5¢ ready to fire; the 6mm and 19 grains of Reloder 7, 7.5¢ apiece; and the 25-06 Remington with 26 grains of Varget and a 120-grain bullet, 8.75¢ apiece. Try matching those prices with any cartridge loaded with a jacketed bullet or even a 22 Winchester Rimfire Magnum.

The gophers had just come out of hibernation the middle of April. Shiny yellow buttercups dotted the wet ground below snowbanks clinging to the shaded slopes. A dozen cow elk trotted out from a ravine, their winter coats shaggy and bleached. I waited until the elk had wandered over the far ridge before I started shooting.

I started with the 223 Remington and the 55-grain RCBS bullet at 2,000 fps zeroed at 100 yards. From the solid rest of a Harris bipod and with the Swarovski scope turned up to 12x, the gophers were easy targets out to 125 yards. Much past that range, though, I had to hold over some to hit. After 100 rounds the bullets began to stick in the rifling when I pulled a loaded round out of the chamber. That was from a dirty bore from lube and powder fouling. For extended shooting, a bullet set back from the rifling would give trouble-free operation. The explosive effect of the bullets on the little gophers carried pretty well out to 150 yards.

The 95-grain 6mm and 120-grain 25-06 bullets didn’t show much eruptive action even up close. These bullets started nearly 300 fps slower than the 22 bullets, yet only 100 fps separated them at 100 yards. Perhaps the long length of the .24 and .25 caliber kept them from tumbling. Even though the two bullets only drilled a hole through the gophers, the little varmints usually gave up the ghost right where they stood, and hawks and ravens started to circle overhead.

I shot gophers until late afternoon. The 300 rounds fired cost less than half a tank of gas for my pickup.

.jpg)

.jpg)