220 Swift Load Development

Breathing New Life into a Classic Cartridge

feature By: Jeremiah Polacek | April, 24

Many folks like to discuss the merits of new rifles and cartridges; it seems that new rifles are the ones that get the most attention in regard to load development. Companies will go to

great lengths to develop pressure-tested data for new cartridges, sometimes seemingly to leave some classic and iconic cartridges behind in the dust to rust. In this article, I wanted to take some measures to address that, such as dusting off a classic rifle that has had many memories and rounds through the barrel and give it some attention. The whole point of this is to compare and contrast how far we have come. Do these old rifles still have merits with updated bullets and propellants? Can the classic cartridges keep up with the more modern cartridges?

To start out, I first wanted to select a cartridge for this test, I could not think of a better cartridge on hand than the 220 Swift, developed around 1935. The speedy cartridge was based on the 6mm Lee Navy and quickly rose to prominence among serious varmint hunters and enthusiasts. To this day, I believe it is still the fastest commercially loaded cartridge. However, with handloading, plenty of wildcat cartridges and even limited Sporting Arms & Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) approved cartridges will outrun the 220 Swift. SAAMI has set the maximum average pressure at 62,000 pounds per square inch (psi), which is on par with many modern cartridges. Considering all of the praises and longstanding reputation of this iconic cartridge, it seemed like a great choice to test with some modern propellants to see if its merits still hold up against more modern cartridges.

The 220 Swift is no slouch regarding velocity, but the most common twist rate for the cartridge is 1:14. This restricts the variety and weight of bullets that can be stabilized in the rifle. This means high-ballistic coefficient (BC) heavy-for-caliber bullets won’t work with a 1:14 twist rate; in my experience, anything much past 62 grains won’t stabilize. Of course, you can always rebarrel your rifle with a faster twist barrel, but that is a topic for another article.

I must admit that I was a little worried that I had a lemon on my hands and getting any meaningful measure of accuracy with this rifle may prove difficult. Nevertheless, the rifle was in pristine condition otherwise, and

The rifle has a Remington SuperCell 1.25-inch recoil pad and sling studs fore and aft. Unlike most modern rifles, the barrel is not free floating, which would make most folks cringe and become concerned with

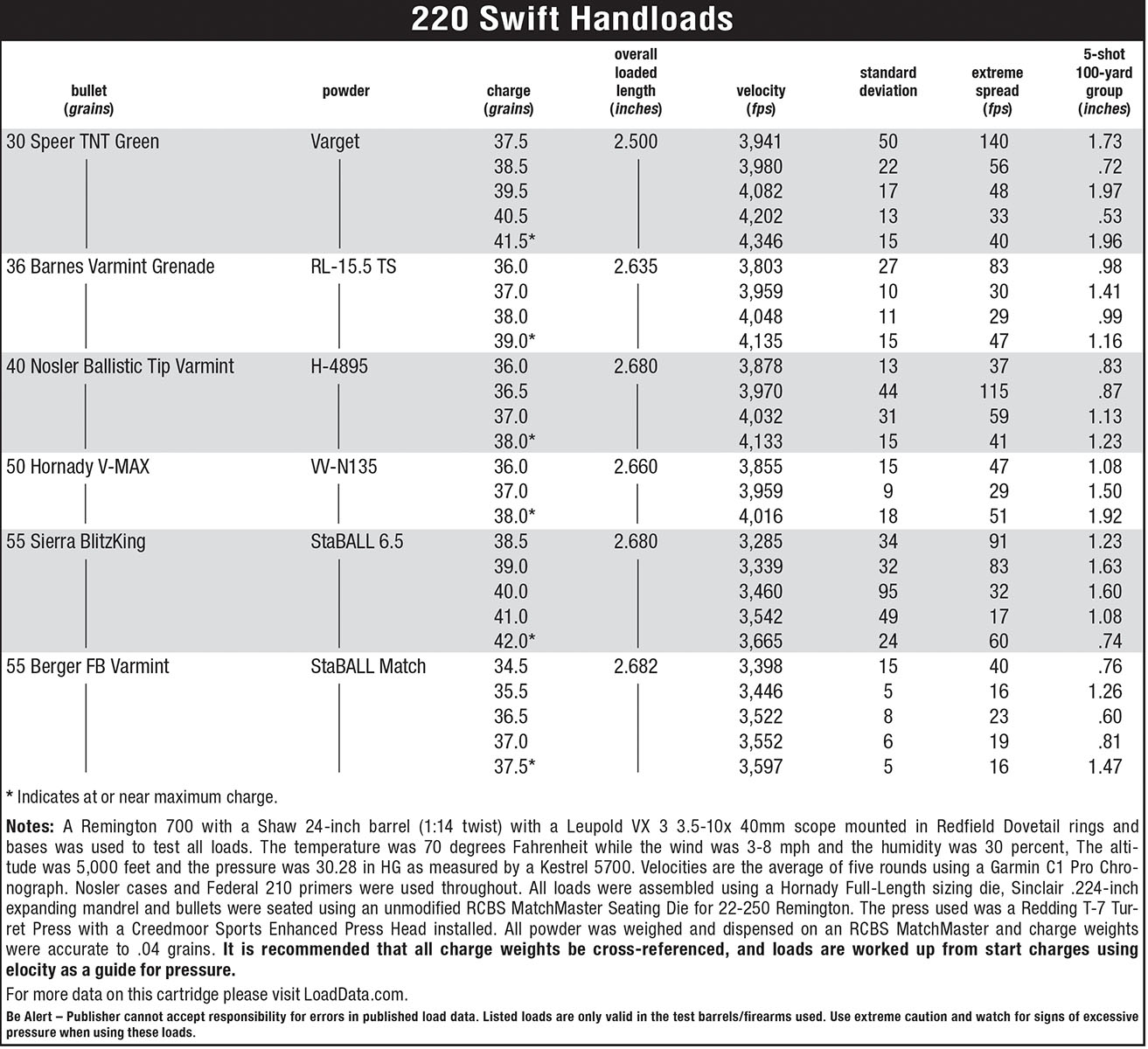

In my quest for load data, I was pleasantly surprised to see that Hodgdon had some load data for its newer powders for the 220 Swift. This immensely helped me assemble some data sheets to conduct proper load development with this rifle. As far as components go, the selection is a bit limited; at the time of this writing, the only companies I could order brass from were Hornady and Nosler. I ordered both, but the Hornady brass was back-ordered and has yet to arrive. Therefore, the Nosler brass was used for this test.

In assembling the rest of the supplies needed for handloading, I decided to use my old tried and true Hornady full-length sizing die, manufactured decades ago. A Sinclair 22 caliber expanding mandrel would be used for the final sizing of the case necks. An unmodified RCBS MatchMaster seating die for 22-250 Remington was used to seat all bullets. I conducted some testing with this die to see if it would work, and

Regarding the press, I chose to use my trusty Redding T-7 Turret Press with the Creedmoor Sports Enhanced Press Head installed. All the cases would be chamfered and deburred using an RCBS Brass Boss case prep center. A Frankford Arsenal hand primer was used for seating primers. All powder charges were thrown with an RCBS Uniflow III powder measure and were trickled up to proper charge weight with an RCBS powder trickler. All charge weights were weighed on a Creedmoor Sports TRX-925 Precision Reloading Scale and were accurate to .04 grains.

With ammunition in one hand and rifle in the other, I set out to test the handloads and see if this rifle could shoot. This took much longer than expected, the temperature of the day was a warm 70 degrees and within five rounds, the barrel was hot to the touch. After another five, the barrel was far too hot to shoot. I had more than 150 rounds to test and letting the barrel cool completely took nearly 20 minutes after a mere 10 rounds! I am a firm believer that letting barrels cool aids in barrel longevity and I am testing loads that are going to be used on varmints and that cold-bore shot is quite important in those situations. I had to think of something to speed things along. Otherwise, this article would not be finished in time to be published.

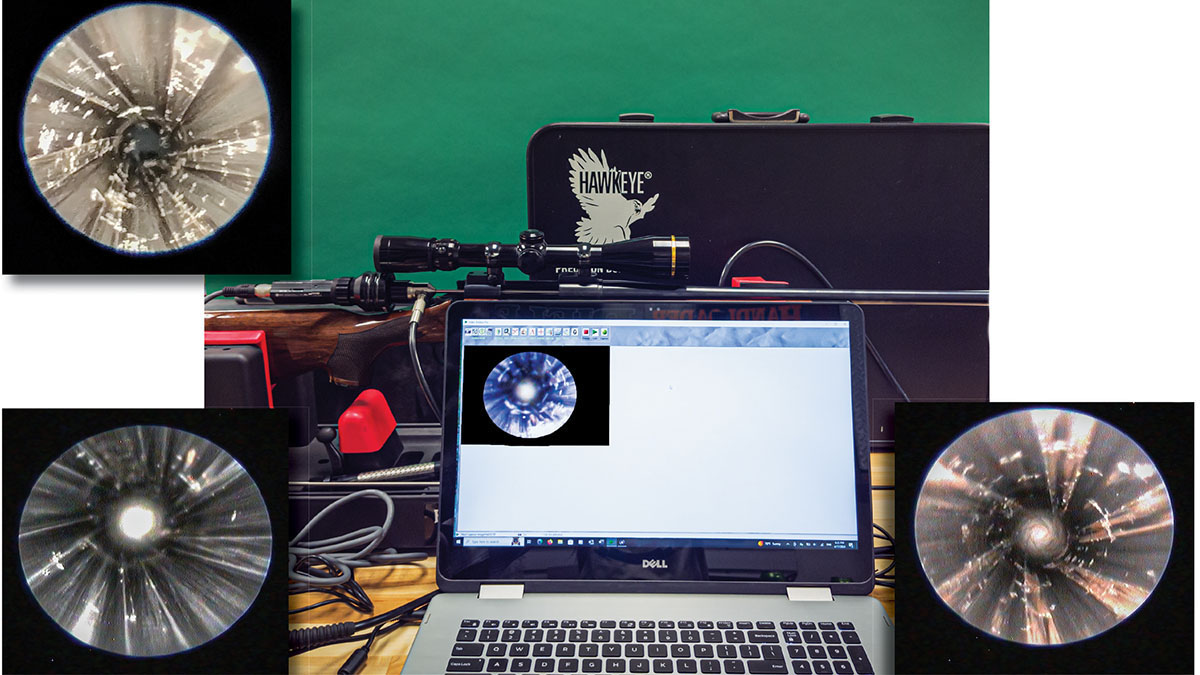

After shooting the first 10 rounds, I was pleasantly surprised to see the rifle put together a nice .72-inch, five-shot group at 100 yards. This significantly alleviated my concerns that the pitting in the barrel and the lack of free float would mean this rifle would not be capable of sub-MOA accuracy. While waiting for the rifle to cool, with my mind mostly relieved of accuracy concerns, I came up with an idea to cool the barrel. My shooting range is a mere couple hundred feet from the shop where there is a large air compressor. There is also a large inline dryer to keep moisture out of the lines. In addition, I had a desiccant snake that I could add to the end of the air hose to ensure that no moisture would come out of it.

With the determination of a gun writer on deadline, a length of hose was quickly run to the shooting position and I was able to push cool, dry air through the barrel, which greatly reduced the time it took to cool the barrel. To double-check my work, I ran a single dry patch through the barrel after speed cooling the barrel, it came out dry. I was able to complete my load development and testing in a matter of hours instead of days. By the end of the test, the rifle had put together some impressive groups. It made me wonder just how accurate the gun would be if it didn’t have the minor pitting in the barrel.

Looking at the load table, we can see that the best loads were pushing towards ½-MOA at 100 yards. If I average the group sizes from all 27 different loads tested, the average group size comes out to 1.15 inches. That is with the best and worst groups all thrown together and a cold-bore shot in every group. That is pretty impressive for a cartridge developed in the 1930s and a rifle more than triple my age!

In testing, the rifle and cartridge performed very well, and I am eager to conduct more testing with these new powders, in particular StaBALL Match and Alliant Reloder 15.5 TS. The results I got with StaBALL Match showed a lot of promise, and with Reloder 15.5, I would like to experiment with a different bullet as I feel the standard deviations were decent enough to warrant more experimentation. In addition to this, there are a few newer Vihtavuori powders I would like to put to the test. I would also be curious to see how Shooters World powders would perform in this cartridge. I am not aware of any published data at the time of this writing; sadly, it would have been too time-consuming to conduct pressure testing for all of these different powder and bullet combinations.

The 220 Swift does have some cons if you will, or at the very least, some things to consider. Sending bullets out of the muzzle at 4,000-plus fps takes its toll on barrels; how much that matters depends on how much you shoot. Also, the barrel heats up very quickly and as I witnessed in my own testing, it can make working up loads quite challenging. Lastly, the 220 Swift is not kind to pelts, coyotes taken with the 220 Swift often have impressive holes left in them.

The cartridge is also semi-rimmed and as a result, it can be finicky when feeding from a magazine. While working up loads for this cartridge, I experienced several malfunctions directly related to the semi-rimmed nature of the 220 Swift. This is often described as “rim jam” or “rim lock,” where one cartridge rim gets caught on another rim and fails to feed from the magazine. Depending on how carefully I loaded the magazine and whether the cartridges were loaded in a staggering formation depended on whether I had issues. This is not something I often hear discussed with the 220 Swift and it may be inherent to this rifle and it’s magazine dynamics or even the bevel on the semi-rim of the cartridge case. However, I thought it was worth mentioning. More Modern Rimless cartridges have no chance of suffering from this issue.

With all that said, the 220 Swift still does hold some weight, especially on shots inside 400 yards. Even at 500 yards, the difference in drop from Hornady factory 22 Creedmoor and 220 Swift is within 4 inches of each other with a 200-yard zero. It holds its own rather well, even when stacked against modern cartridges with heavier, higher-BC bullets. It might not be the most efficient cartridge, and getting components such as brass and dies may be difficult or expensive, but from a pure performance standpoint, the 220 Swift still holds its own.

Overall, having shot both new cartridges and older cartridges extensively, I still think a classic cartridge such as the 220 Swift can earn a spot in the modern varmint hunter’s safe.