19 Badger

A Necked-Down 30 Carbine

feature By: Jim Matthews | October, 18

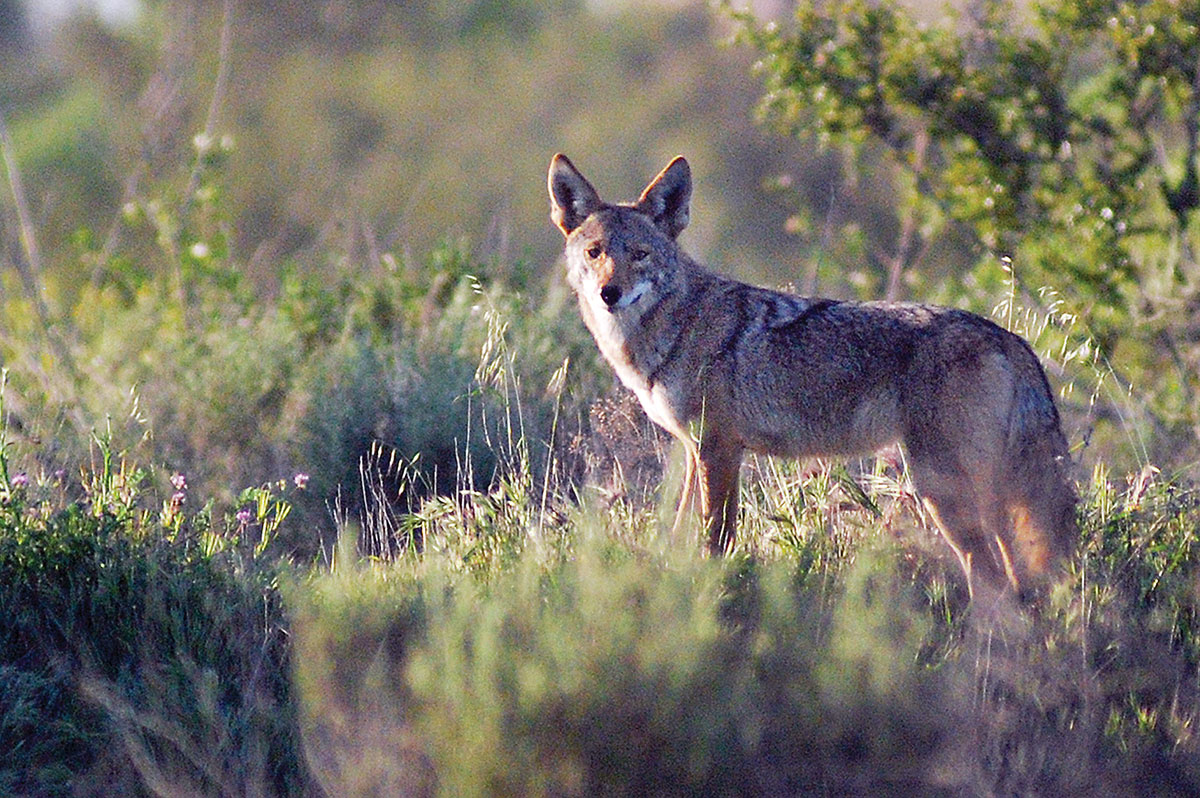

There might be some hyperbole in that statement, but you get the point. The activity involves the burning of lots of powder. There are four factors that lead to the creation of the perfect volume-shooting cartridge: First, recoil must not be excessive; even modest recoil can induce flinches and trigger jerks after 100 rounds. Even more importantly, if recoil is so slight you can see the bullet impact on the target, you have a round that passes the first test of the volume shooting.

Second, barrel fouling must be minimized. If accuracy degrades after 30 or 40 shots because of a fouled barrel, it requires cleaning. If copper fouling is bad, it requires thorough scrubbing. Cleaning takes away from trigger time. This problem is partially solved with new, cleaner-burning powders, and bullets that minimize fouling. Likewise, cartridges that work at modest velocities and burn less powder generally require less cleaning.

Third, the cartridge must have enough energy to perform when the bullets connect with small rodents, and the rifle must be accurate from 25 to 250 or even 300 yards, where most volume shooting is conducted.

Last, there is a “coolness factor.” The 22-250 Improved is a cooler round than the factory 22-250. Wildcats are more interesting than factory rounds, and exotic wildcats are better still.

Leahy and his varmint-shooting buddies mulled over the 19 for a few winters before finally deciding it might be the perfect caliber for their varmint needs. They settled on two initial cartridges to neck down to 19 – the 22 Hornet and 223 Remington – and built the first versions in the winter of 1997-98, the 19 Calhoon Hornet and the 19-223 Calhoon.

The 19-223 Calhoon was ideal for longer shots, but the 19 Calhoon Hornet, while nearly matching 223 ballistics and trajectory – was perfect for volume shooting out to 300 yards. It had some drawbacks; brass was thin, rimmed and did not last all that long.

By the mid-2000s one of Leahy’s friends started tinkering with the 30 Carbine case, and they quickly realized their woes with the Hornet case were over. The 30 Carbine has effectively the same head diameter as the Hornet at the rim. It was rimless and designed for higher pressures, and it held about three grains more powder than the 19 Calhoon Hornet.

On the first test run, several varmints were plunked with the new 19, and they came to call it the 19 Badger. By 2007 Leahy was selling more 19 Badgers over the Hornet version, and now he provides brass and loaded ammunition made with Starline 30 Carbine cases sized and loaded in the Calhoon shop.

The test rifle used for this story was one of Leahy’s CZ 527s rebarreled to 19 Badger using a Benchmark, hand-lapped, stainless steel barrel with a 1:13 twist. Leahy supplies these rifles with a slick magazine substitute that replaces the magazine that hangs down in front of the trigger guard. The replacement makes the rifle into an easy-to-feed single shot, leaving a smooth forend without a magazine protruding below the stock. Calhoon also modifies the factory bolt to make it sleeker and to accommodate scopes in lower mounts. For shooting, a Burris Fullfield E1 4.5-14x 42mm riflescope was used in Leupold rings designed for the CZ.

Since Calhoon supplies Starline brass at very reasonable prices, there is no need to go through the case forming, fireforming, neck-turning process. The first group shot with some old 27-grain Calhoon bullets I had on hand with a starting load of Accurate 1680 produced a five-shot group of .63 inch. That turned out to be a pretty average group for this rifle with the more accurate loads I tested.

The accompanying load table lists the powders in the burn rate category that work best with this cartridge. Leahy thinks Accurate 2200 is probably the best powder for the 32-grain bullet, but none was available when testing. I did work up loads with CFE BLK powder introduced just two years ago.

Varmint shooters should note that working up loads in .2-grain increments is the routine because pressures can jump quickly with small changes in powder charges. Leahy recommends measuring case heads before and after shooting new loads, and backing off a full .5-grain of powder if the case head expands even .0001 inch. The loading data he supplies lists maximum loads – and these need to be considered maximum and approached with caution because they might be overpressure in another rifle. I found this to be exactly the case.

It is routinely reported that small cases are more sensitive to ambient temperature changes, with pressures rising in hot temperatures. So when working up loads for the test rifle, I thought this was the reason I was reaching maximum velocities and top pressures at .5-grain below Leahy’s maximums with two different powers. In my load tables, the 15.1-grain load of Accurate 1680 and a 32-grain bullet gave a velocity of 3,585 fps. The load matches the velocity of the 15.6-grain load Calhoon’s data shows as maximum. When the charge was increased, excessive pressure signs became obvious.

Shooting with nearly identical components and rifles, the dramatic difference in my loads and those listed by Calhoon was confusing. Was it air temperature or something else? I had the opportunity to shoot identical loads with Calhoon’s old 27-grain bullet in the Badger on two different temperature days – one on a cool 60-degree Fahrenheit day, and the other a sweat-inducing 90-degree morning. There was almost no difference in the readings.

My velocities (and pressures) were obviously higher across the board than in the Calhoon data supplied with the rifle. All top loads where I approached or met the Calhoon maximums showed pressure signs, and cases stretched significantly, requiring trimming.

After careful reading and re-reading the load data supplied by Calhoon, and after a couple of discussions with Leahy over the phone, it was decided that the difference was one of two things (or perhaps a combination of them): First, the powder lots I used were different enough in burn rate from those he used to cause the differences. This was the direction Leahy was leaning.

Second, I noticed in the tiny type of his load data that his tests were run with Remington-Peters reformed brass. All load data here was shot using the Calhoon cases made from Starline brass. While I did not have other brands of 19 Badger brass to measure case capacity against the Starline cases, I had been down that road before, finding dramatic case capacity differences in different brands – and even the same brands if manufactured years apart. In those tests, I had found that case capacities varied by as much as 4 percent between brands – more than enough to spike pressures if used with the same maximum loads. That was probably the reason for reaching the maximum velocity/pressure levels with – on average – .5-grain less powder (a 3 percent change) in the Starline cases as opposed to what it took Calhoon to reach that level in the Remington-Peters cases.

The bottom line is to always start with minimum powder charges and work up carefully when developing new loads for any cartridge – or when any component is changed from existing loads.

I viewed the ability to shoot .5 grain less powder to reach good velocity levels as a good thing for volume varmint shooting. Using 15.5 grains of powder instead of 16.0 grains means you will get an additional 14 loads out of a one-pound canister.

Case trimming with Wilson-style case trimmers is a snap with the Badger. However, if you have a Forester-style trimmer, .19-caliber pilots have to be custom made – or you can use a .20-caliber pilot and trim the case before resizing. I used this method. I also measured the trimmed cases before and after sizing, and noticed they stretched .001 to .002 inch just in the sizing operation.

“Compared to the Hornet, the Carbine case works under more pressure and is way stronger brass,” said Leahy. His testing with cases showed they would last 20 loadings or more.

While spending a little time with the CZ rifle in the field, I managed to shoot a few California ground squirrels and a couple of blacktailed jackrabbits, with devastating effect, at ranges from about 25 yards to just under 200 yards. The things I appreciate most about the little .19 caliber is a lack of noise. Both my older 19 Calhoon Hornet and the new 19 Badger have a crack that is about the same as a 22 or 17 HMR, allowing for their use in relatively close quarters to residential areas. A booming 22-250 Remington sounds ominous.

While I do not do as much volume shooting as I once did, the old 19 Calhoon Hornet became a staple in my varmint hunting battery. After shooting the 19 Badger, I wished it was around back when I bought the 19 Hornet conversion kit in 2000 to turn my Ruger 77/22 Hornet into the 19 Calhoon Hornet. Leahy said the Rugers did not convert well to the 19 Badger because the lock-up just was not as strong or rigid as the CZ mini-Mauser action. But then I’ve always wanted one of the little CZ 527s, and the 19 Badger would not be a bad choice. Visit jamescalhoon.com or call (406) 395-4079.