Varmint Scope Reticles

Sorting Through Benefits and Distractions

feature By: John Haviland | October, 18

The scope was used so much over the following years the paint wore off all the magnification markings. That scope taught me a lot about judging distance by the apparent size of a prairie dog or coyote as viewed in the scope, and how much to compensate for the ever-changing wind. The 22-250’s flat trajectory made countering bullet drop fairly easy. All I had to do was place a sliver of daylight between the crosshairs and top of the head of a marmot sitting upright at 400 yards to knock it off its perch.

Over the years, reticles have progressed to the point that a scope containing a plain crosshair reticle is thought inadequate for even rimfire rifles. Modern reticles contain dots or hash marks spaced on the lower vertical wire to match the trajectory of cartridges firing certain bullets at specific velocities. Marks on the horizontal wires increasing in width denote holds to compensate for wind drift. Other reticles require logging onto the optics company’s website and typing in pertinent environmental conditions and ballistic information about a load to create a “ballistic program” that meshes with the reticle’s hold-over points. Still other reticles have wires marked in inches, minutes of angle (MOA), or milliradians that, with some shooting at various distances and some experience, can mesh with the ballistics of nearly any load. All these reticles so common today would be of little use if laser rangefinders had not also come into widespread use.

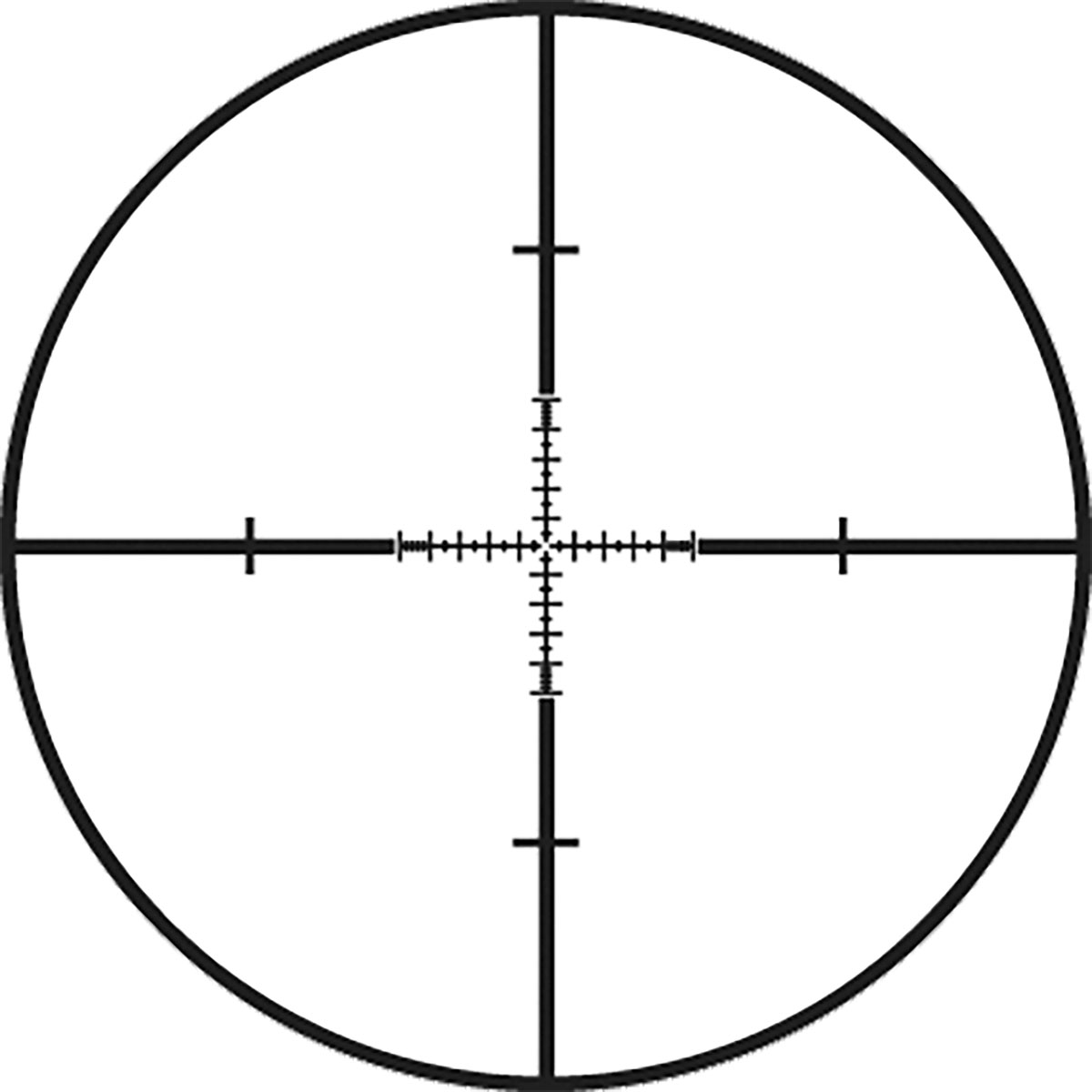

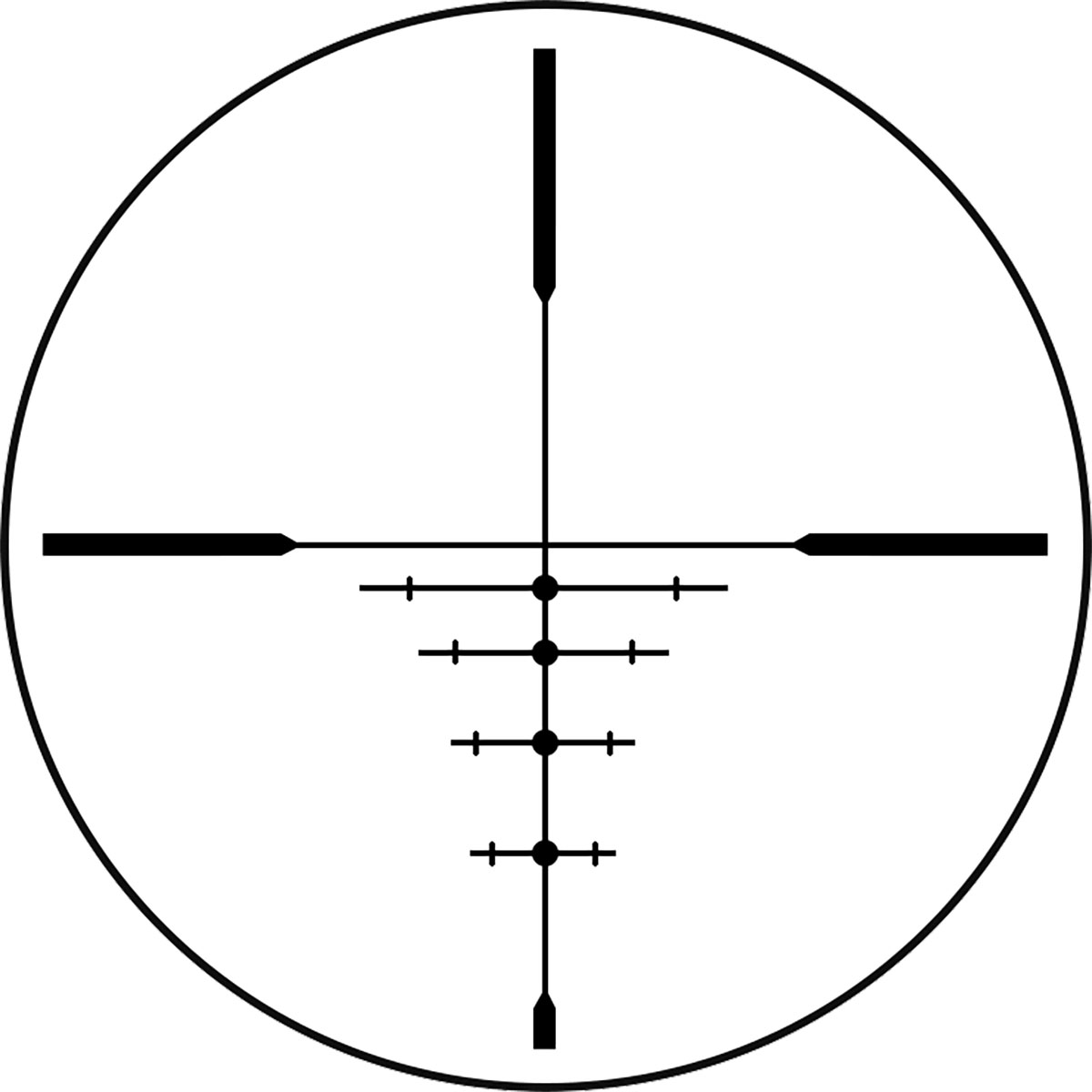

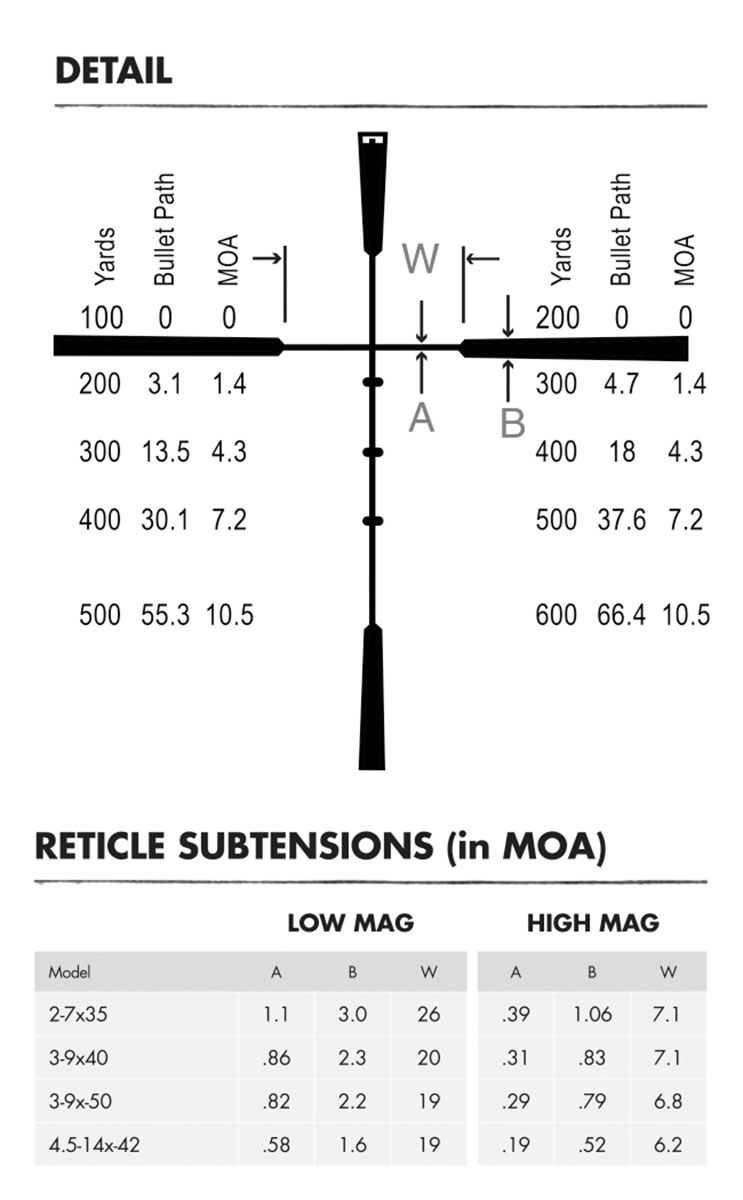

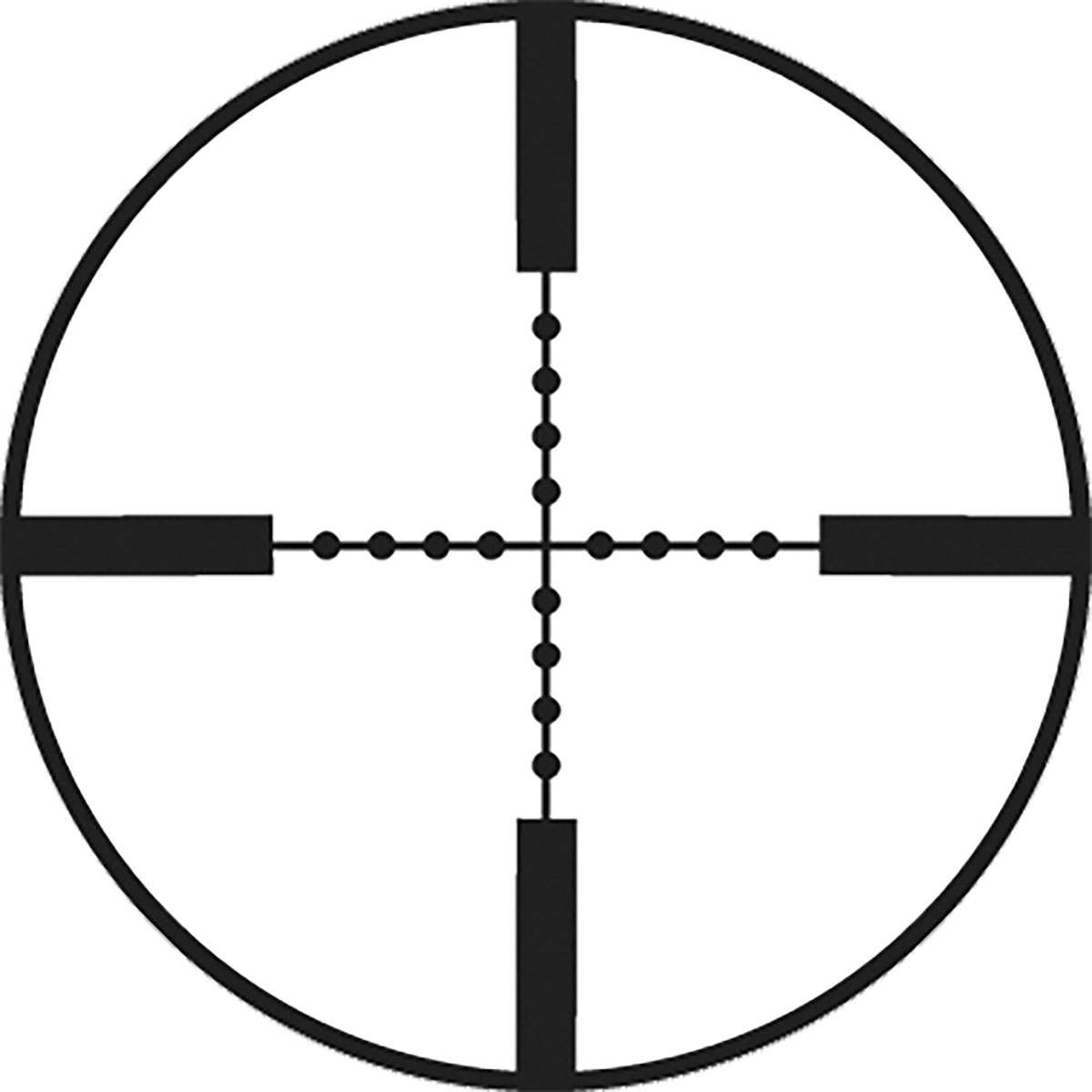

Probably the first reticles with multiple aiming points were similar to the Zeiss Rapid-Z, Burris Ballistic-Plex and Leupold Varmint Hunter’s reticles. I’ve used the Varmint Hunter’s reticle the most in a VX-III 4.5-14x 50mm scope on a Cooper Model 22 243 Winchester.

A great long-range prairie dog load for the 243 is Nosler 55-grain Ballistic Tip bullets fired at 3,800 fps. For the Varmint Hunter’s reticle to match the Ballistic Tip’s trajectory, I sighted them in at 300 yards. Then the first hash mark down was my 400-yard hold, the second bar down a 500-yard hold and the third down a 600-yard hold. Bullet trajectory and the hash mark come within 3 inches of meshing at 600 yards. The 600-yard figure came from a ballistics program, as I have never shot the rifle on targets that far.

But I have shot the 243 at ground squirrels out to 500 yards. The bullets start a steep plunge after 350 yards, and even a 25-yard miscalculation in distance causes a miss. So, some skill is required to aim a touch high or low with the correct hash mark. Of course, the wind is ever-present. The ends of the hash marks provide holds for a 10-mph wind while dots out from the lines provide holds for a 20-mph wind. I often judge wind velocity as being faster than it is, and my hopes riding on a bullet end up plowing the ground.

Imagine mirage is roiling across the prairie on a hot summer afternoon. Peering through the scope set on 14x, it looks like ground squirrels are swimming in a pond. Turning the scope down to 10x helps lessen distortion, but that causes bullets and the various aiming points to go their separate ways.

I did much the same by shooting and turning to different magnifications with the Leupold VX-2 3-9x 33mm EFR Rimfire scope on my 22 rifle. The center of the fine Duplex crosshairs to the tip of the lower post encompassed 6 inches at 100 yards with the scope turned to 6x. That 6-inch span is just about the same distance CCI Mini-Mag 36-grain HP bullets drop at 100 yards when zeroed at 50 yards. So when shooting gophers at 100 yards, I turn the scope to 6x and aim with the tip of the post. If I had the ambition, a ballistic chart could be created for the scope set on different magnifications, but I would rather shoot gophers than paper targets.

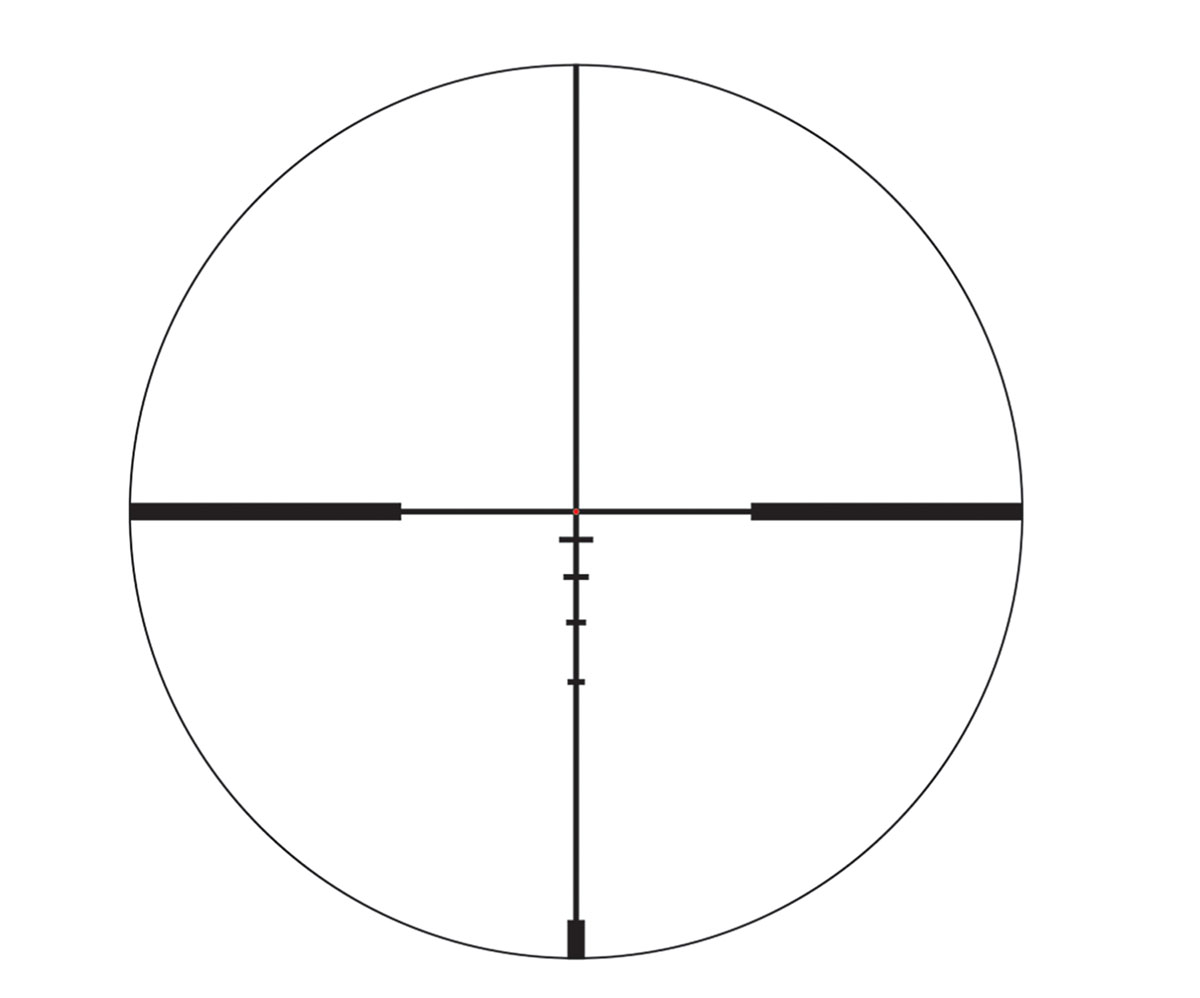

All this computing is unnecessary with a scope’s reticle placed in the first focal plane. A reticle placed in front of the erector assembly appears to grow larger as magnification increases, and smaller when magnification decreases. Actually, the reticle maintains the same scale with the target size, and hold-over values remain the same no matter where the magnification ring is set. One disadvantage of a first focal plane reticle is that it appears to shrink as magnification is decreased. Leupold’s Mark 5HD 3.6-18x 44mm scope has its reticle in the first focal plane. Set much below 8x, though, it is difficult to see the hash marks and distinguish the spacing between them. The reticle works best as plain crosshairs at that power and lower.

Inches are easy to relate to because that’s how Americans measure everything from boards to tines on a buck. Say a scope’s reticle is marked with an inch scale at 100 yards. The 55-grain bullets fired from your 22-250 drop 15.60 inches at 400 yards. To compensate, count down four division marks (actually 3.9; 15.60 divided by 400 multiplied by 100 equals 3.9), aim with that mark and pull the trigger.

One MOA equals 1.047 inches at 100 yards and to calculate MOA at any distance, multiply 1.047 by the distance in yards and divide by 100. So one MOA at 400 yards equals 4.18 inches at 400 yards. The 22-250’s bullet drop of 15.60 inches at 400 yards then equals 3.72 MOA. To compensate, aim a tick less than four MOA marks – aim with that mark and pull the trigger.

One MIL equals 3.6 inches at 100 yards and 14.4 inches at 400 yards. That one MIL is about equal to the 22-250’s bullet drop, so aim up one MIL hash mark and pull the trigger. MILs are easy to use when we think in MILs. If a bullet drops 36 inches at 500 yards a varmint shooter can make a quick conversion and think of that drop in MILs.

Some MOA and MIL reticles are filled with too many closely spaced dots or hash marks. That clutter obscures the target, and I have to carefully count down the marks at least two times to make sure I’m aiming with the correct dot. The Trijicon AccuPoint 2.5-12.5x 42mm is available with an MOA Dot Crosshair. Dot diameters are .65 inch, with three on each side of the center of the reticle on the horizontal wire, and six on the bottom vertical wire. Dot spacing is 2 MOA and provides an uncluttered view. The Leupold Mark 5HD 3.6-18x 44mm Tactical Milling Reticle scope uses hash marks, instead of the more common dots, spaced .5 MIL apart on the horizontal and vertical wires. The hash marks are thin, and along with the wider spacing, the reticle wires remain uncluttered.

A trend today is to compensate for bullet trajectory by adjusting turrets made for twirling. I have watched people shoot at prairie dogs by taking a distance reading with a rangefinder, dial their scope’s elevation knob to compensate, and finally take a shot. They go through the same process over and over. Eventually, they forget where the turret is set and, thankfully, have a dial with a zero stop they can turn back to and start over. Their rifle’s barrel will never overheat because it takes them a whole morning to fire 20 shots.

Turning turrets while calling predators does nothing but reveal yourself. Last winter a friend and his son were calling coyotes. A coyote came running across a sagebrush flat but stopped far out to consider the risks of a “free meal.” The dad gave his son a range to the coyote, and the son reached up to dial the elevation turret on his AR-10 308 rifle. The coyote saw the movement and turned nearly inside out clearing out of the country. The 20 cartridges in the magazine failed to correct the mistake.

To verify no little varmints can escape unscathed due to a disparity of the Battlezone’s BDC reticle and my ammunition, I tested the scope with the 10/22 shooting Remington Cyclone loads with 36-grain hollowpoint bullets at a muzzle velocity of 1,280 fps, which is pretty close to the recommended 1,260 fps. All the way out at 150 yards, bullet impact was only an inch off aim.

The first time out with the 22, I sat overlooking a flat full of gophers. Most of them were about 75 yards away, and I turned the elevation dial to match. I aimed right on vertically, sometimes more than a hash mark to the side, judging the wind by the wafting of the peach fuzz in my ears. Quite a few gophers ascended to that clover patch in the sky. On somewhat closer and farther shots, I eyeballed the distance and aimed with one of the higher or lower hash marks. It seemed more precise to aim with a mark placed slightly high or low on a gopher than splitting the difference by placing a gopher between lines. The fun stopped only when I ran out of ammunition.

Today’s reticles featuring dots and dashes certainly make varmint hunting far more effective than it was eons ago when plain crosshairs made us estimate where to hold. However, judging the exact hold, and hold off to compensate for the ever-changing wind, still makes varmint hunting a challenge.