250-3000 Savage

Mordern Powders and Lightweight Bullets

feature By: Jim Matthews | April, 15

If the round was introduced today loaded with modern bullets and powders, and with the marketing genius of contemporary Arthur Savage thrown in, it would still get a lot of attention from shooters for its attributes – and it should. With a fresh look, it’s easy to see the old cartridge is still pretty potent, even when stacked against modern .22 centerfire cartridges. The 250 Savage was years ahead of its time.

At the very least, the 250-3000 encapsulated the history of varmint hunting in this country, and it set the stage on how to successfully design and market cartridges for the hunting and shooting community. Its story still rings fresh.

Charles Newton designed the 250-3000 cartridge for Arthur Savage’s Model 1899 rotary-magazine, lever-action rifle. Other leverguns of the era had long, tubular magazines attached beneath the barrel requiring the use of flatnosed bullets. While they held more rounds than the new bolt-action guns being phased into use around the rest of the world, they were often looked upon as short-range guns. The Savage Model 1899 grabbed the American hunter’s passion for leverguns and paired it with a magazine that allowed the use of pointed bullets and higher velocity cartridges in its comparatively strong action.

Savage was probably well aware of the news from Canada that the 280 Ross was hurling a bullet at 3,000 fps – the first time any bullet had left the end of a barrel at that velocity in a rifle cartridge. He wanted to match or top that, and it could be done with an 87-grain bullet. It has been suggested that Newton stood fast that the cartridge wouldn’t be as effective on game without a 100-grain bullet. Regardless, Savage knew what would sell more firearms.

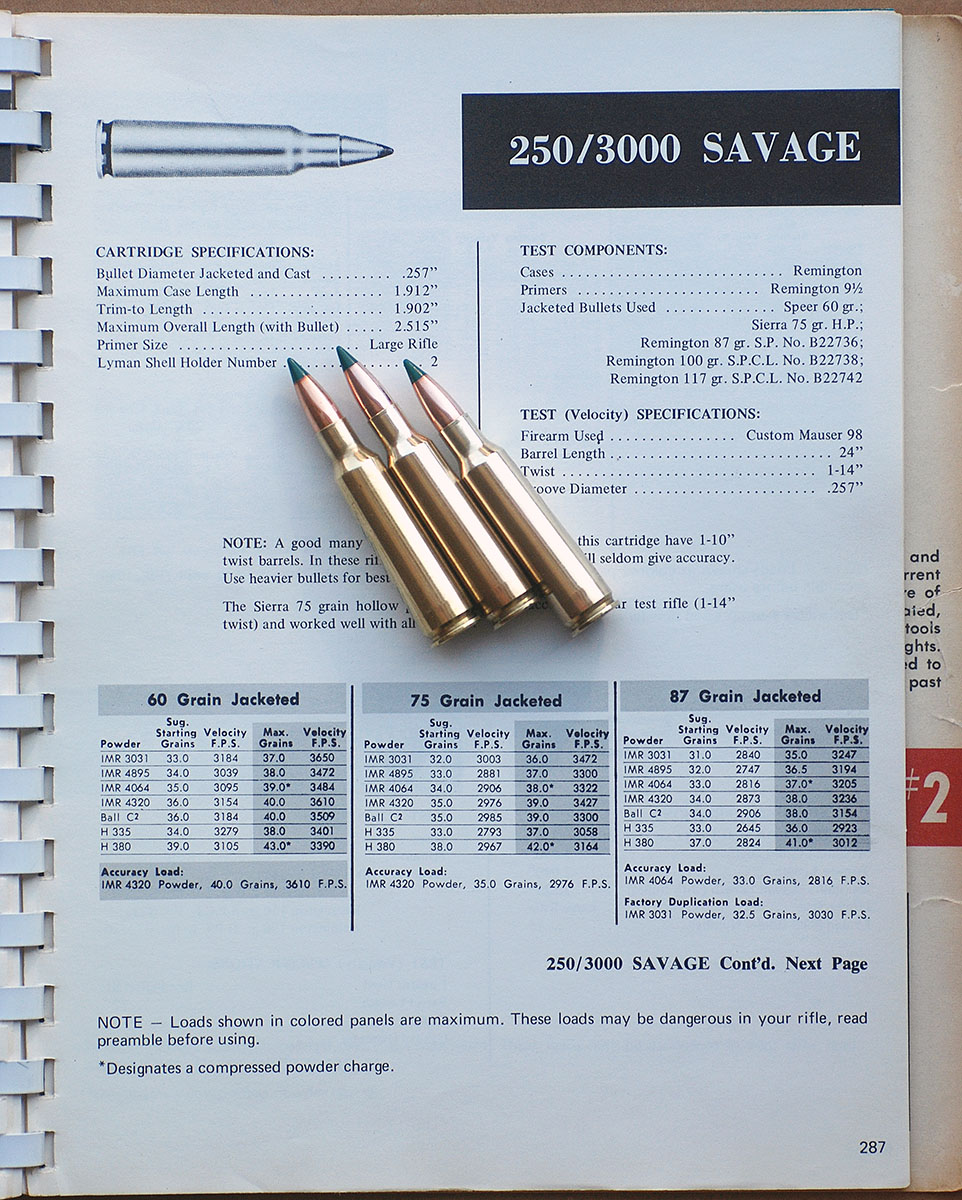

If Savage made a mistake, it would be that the early 1899s and Model 99s (“18” was soon dropped from the model designation, probably because it made the gun sound so last century) chambered in 250-3000 had a one-in-14-inch twist barrel. They wouldn’t stabilize bullets heavier than the 87-grainers, but later guns were made with 1-10 twists so could stabilize 100- to 120-grain bullets as well as the lightweight slugs.

As a big game round, the 250-3000 Savage might have been borderline with 87-grain bullets (although a lot of deer punched in the ribs with those old cup-and-core bullets died quickly), but as a varmint round it was a couple of decades ahead of its time.

Varmints have been potted as long as there have been hunters, but the era between the two world wars was really the beginning of varmint hunting as we know it today. It was also when riflescopes first starting becoming available and accepted by the hunting public. With a good peep sight on a 250-3000 Savage, a skilled hunter might be able to consistently hit a groundhog at 150 yards. Add a scope, and the range increases with the power of the optic. By the mid-1930s, scopes from 2½x to 4x were common, and there were a few companies making scopes up to 10x that were ideal for long-range varmint work.

Accurate shooting at 200 to 300 yards or more was suddenly possible, and the era was rampant with wildcat varmint cartridge development. Shooters wanted flat-shooting, low-recoiling rounds with highly frangible bullets. The 250-3000 Savage was one of the few factory rounds available that met these criteria as this craze took off, and a lot of nice custom Springfield and Mauser rifles were put together with varmints in mind. It was during this time that shooters saw the first introduction of centerfire rounds designed primarily for the varmint hunting marketplace.

Perhaps the most popular cartridge, however, was a wildcat based on the 250 Savage, the 22-250. Adventurous handloaders boosted 40-grain bullets to 4,000 fps with the powders of that era – even before the introduction of the 220 Swift – but most were using 50- and 55-grain bullets at more modest velocities.

It wasn’t until after World War II, however, that varmint hunting became a mainstream activity. Optics had become better and cheaper, and all major rifle manufacturers entered the varmint rifle marketplace. Remington introduced the 222 Remington in 1950, followed it up with the 222 Remington Magnum and adopted a commercial version of the new 5.56 military round, the 223 Remington. Roy Weatherby, as much a master of high-velocity hype as Arthur Savage, introduced his 224 Varmintmaster in 1963, a virtual ballistic copy of the 22-250. Winchester, still hung up on rimmed cases, came out with the 225 Winchester in 1964.

It took Remington until 1965 to standardize the most popular of the wildcats by making the 22-250 a factory round. Almost overnight, it surpassed its parent case and all other varmint rounds in popularity. Varmint hunting and the 22-250 Remington became as intertwined as deer hunting and the 270 Winchester.

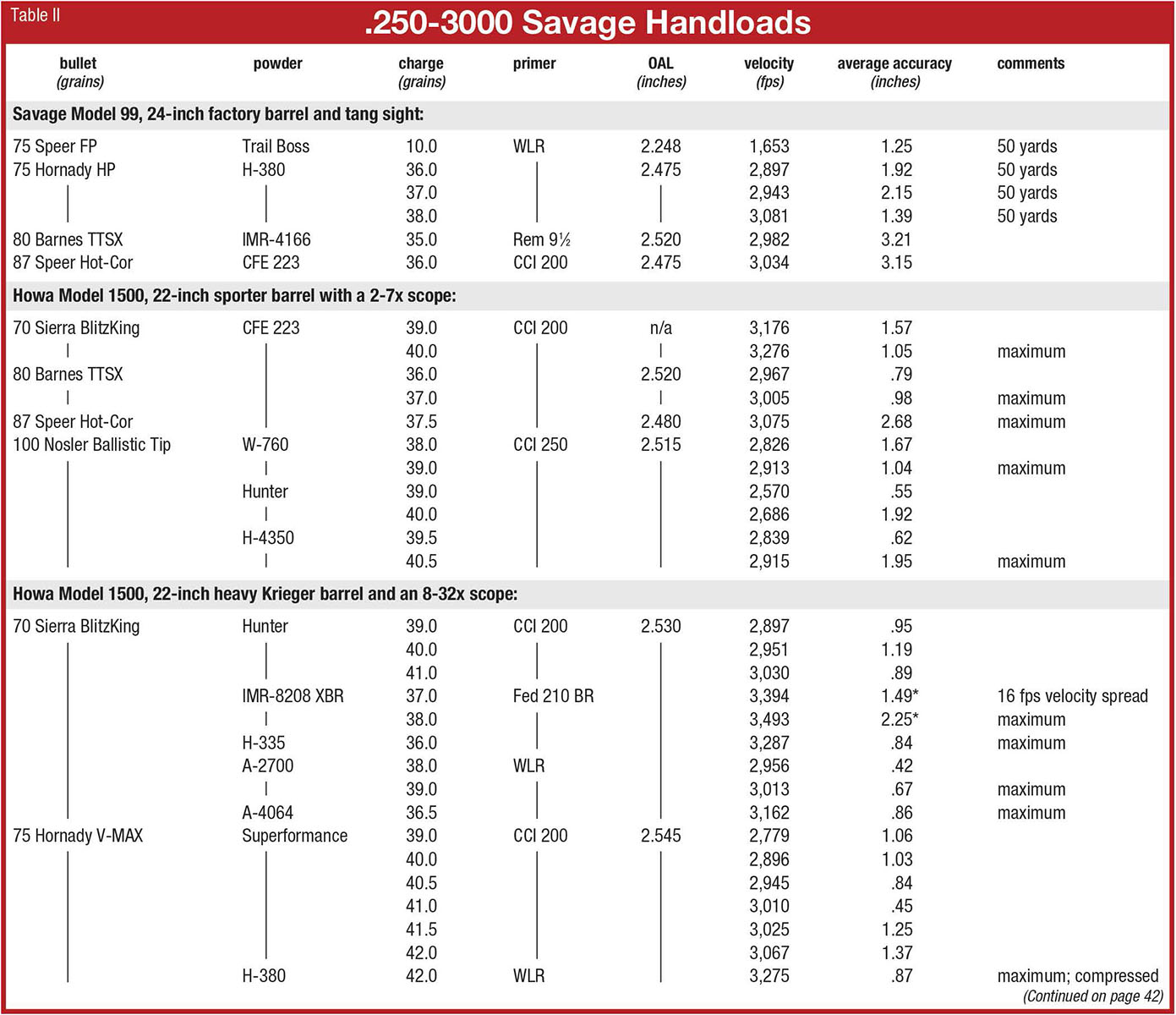

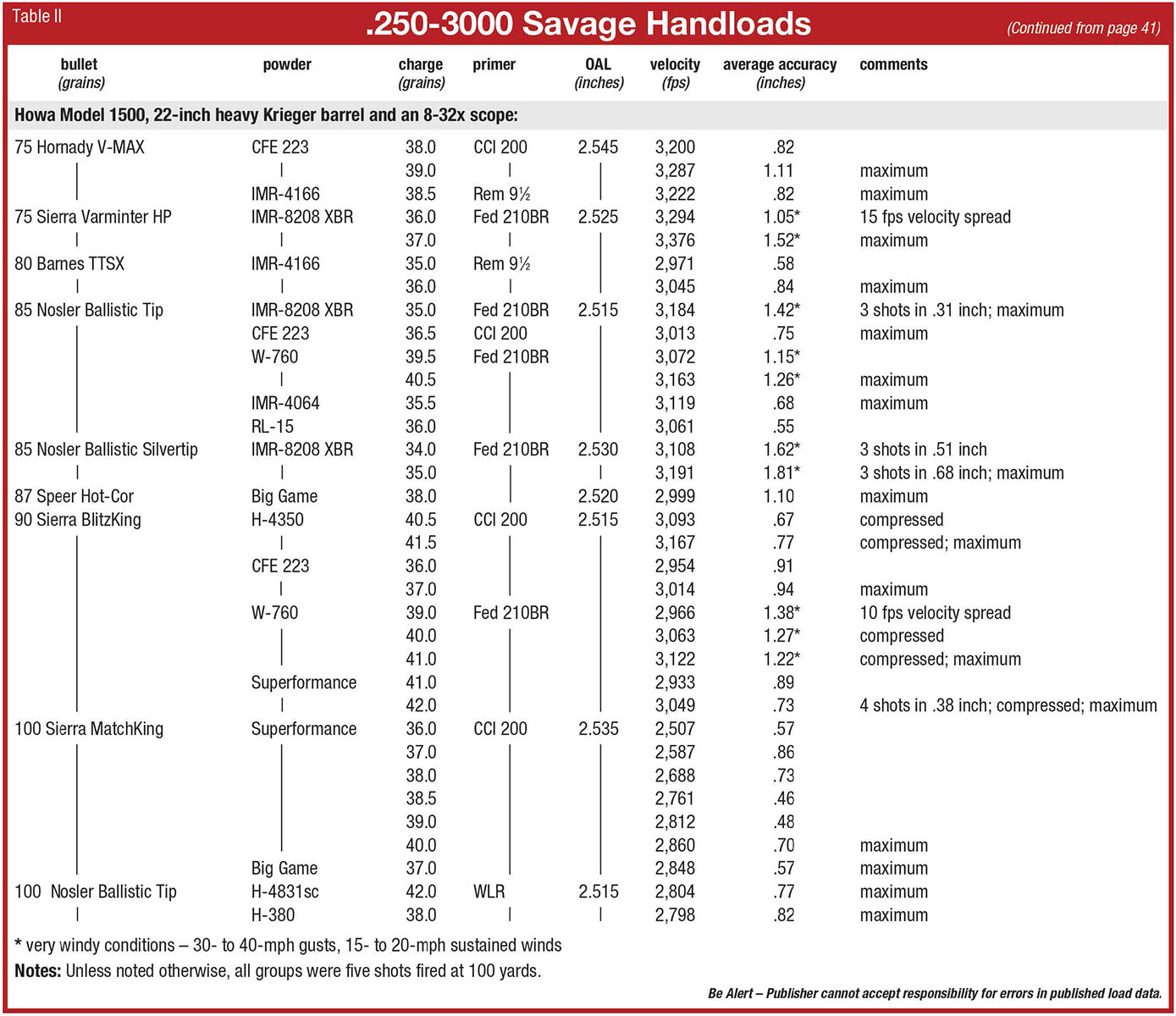

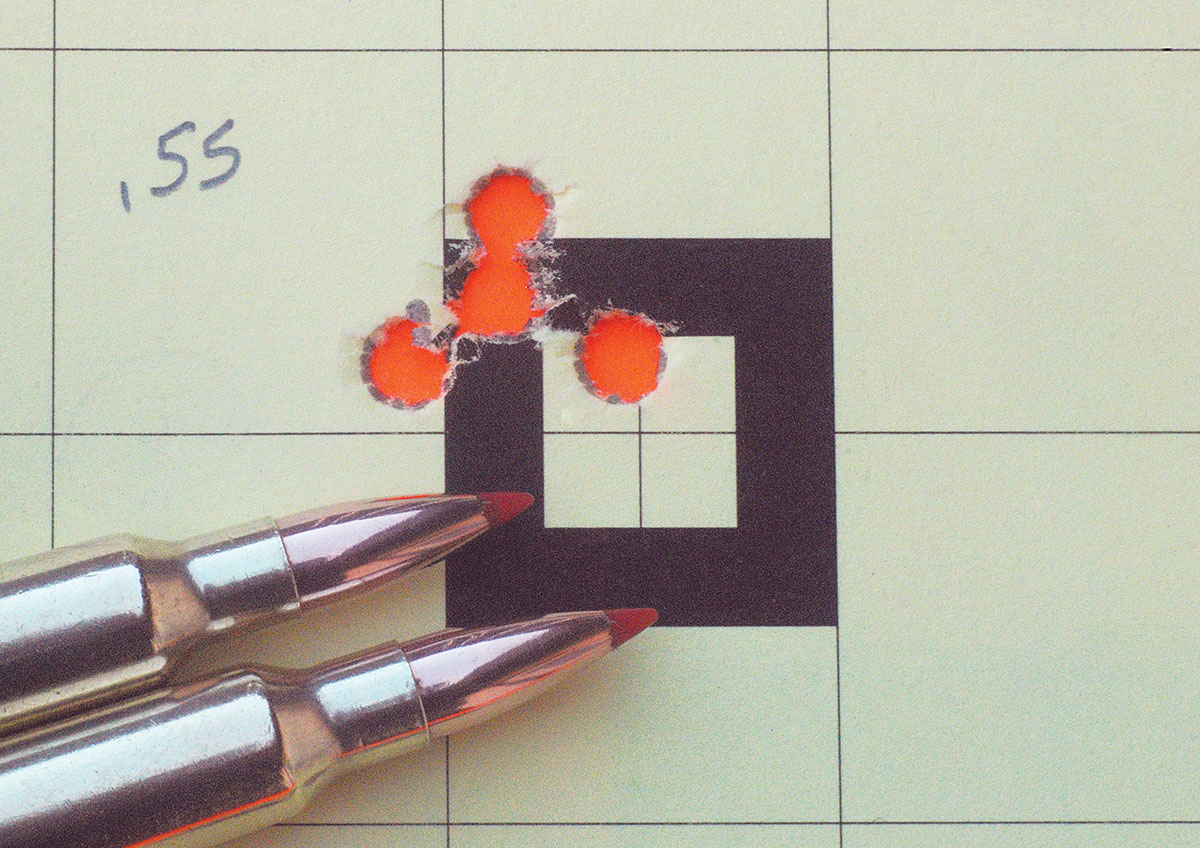

Few varmint hunters today ever consider the 22-250 Remington’s parent case, the 250-3000 Savage, or the man that designed it (or the other that sold it). I have a heavy-barreled 250-3000 Savage built on a Howa 1500 action by California gunsmith Jim Gruning more than a decade ago. Its Krieger barrel is 22 inches long with a one-in-10-inch twist. With several loads this rifle will shoot .3- to .4-inch groups all day if the conditions are good and the shooter can do his part.

A couple of years ago, I also picked up a refurbished Savage Model 99 with a 1-14 twist that I fitted with a nice tang peep sight. I immediately started shooting close-range ground squirrels with low-velocity Trail Boss loads in this rifle. A good friend also had a 250 Savage sporter made on a Howa 1500 Lightweight for pronghorn. I was tasked with working up a couple of big game and coyote loads for that rifle.

Early on in loading for this round, things were discovered: First, brass was expensive if a proper 250 Savage headstamp was required. That cost could be cut in half by simply re-forming 22-250 Remington brass. It’s a one-step process with a 250-3000 Savage sizing die, and there is a minuscule amount of fireforming that takes place. Second, the loads in all the reloading manuals don’t exceed the very mild pressure established by SAAMI for older rifles like the 99, so I’ve never really worried about using loads that were “too” hot when working up to maximum in the two Howas. Even the “maximum” book loads have proven very mild in the two bolt guns. For the Model 99, loads are kept below maximum levels; brass lasts forever, recoil is about like the .22 centerfire cartridges, and it will reach way out there.

Even when staying within the maximum pressure prescribed by SAAMI (45,000 CUP for the 250-3000 versus 53,000 CUP for the 22-250), new powders and light bullets can really make the 250-3000 seem like a contemporary varmint cartridge. The accompanying load table shows this very well. It’s pretty simple to get 3,450 fps with the 70-grain bullet and 3,300-plus with 75-grainers.

I was able to duplicate the 1915 data for the 87-grain bullet out of the Model 99 with a very mild load of 36 grains of Hodgdon CFE 223 powder. While still 1.5 grains below the maximum listed for this powder, velocity was 3,034 fps out of the 24-inch barrel. Hodgdon lists 3,150 fps for the maximum load of 37.5 grains of CFE 223 (24-inch barrel), but that load only produced 3,075 in one of the 22-inch Howa barrels.

The most consistent powders in my rifles were IMR-8208 XBR (with light bullets) and Winchester 760 (with heavier slugs). Both had extreme velocity spreads of 15 fps or less across five shots. Western Powder’s Accurate 2700 and 4064, along with Hodgdon’s CFE 223 and Superformance, also showed very good shot-to-shot consistency, and limited testing with IMR-4166 also produced very low extreme velocity spreads and good accuracy.

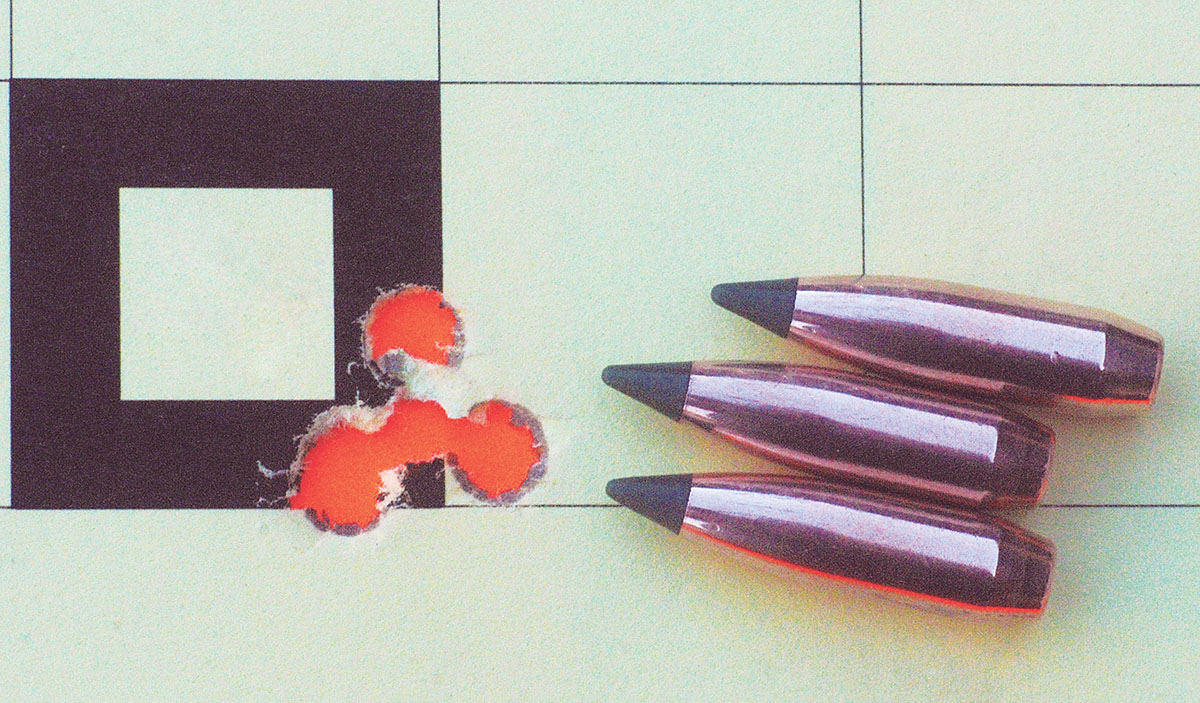

If you have a one-in-14-inch twist barrel, it is not likely to stabilize many modern bullets over 80 grains, with the stubby, old-style 87-grainers usually an exception. I shot a trio of Sierra 100-grain MatchKings from my Model 99, and the three-shot “group” was 7½ inches at 100 yards, and the bullets were going through the paper sideways. I was pleasantly surprised, however, that the Barnes 80-grain Tipped Triple-Shocks stabilized from the same rifle, while Nosler 85-grain Partitions keyholed.

The 250-3000 may be old, but it’s certainly capable of being put to good use as a varmint cartridge, especially in a bolt rifle with a proper rifling twist for lighter bullet use.