Crockett Rifle

The Original .32 Critter Gitter

feature By: Gary Lewis | April, 23

We call them grey diggers or simply diggers, ground squirrels that - nose to tail - measure anywhere from 12 to 16 inches. They make their homes in dens in the ground, living in small groups and in great colonies.

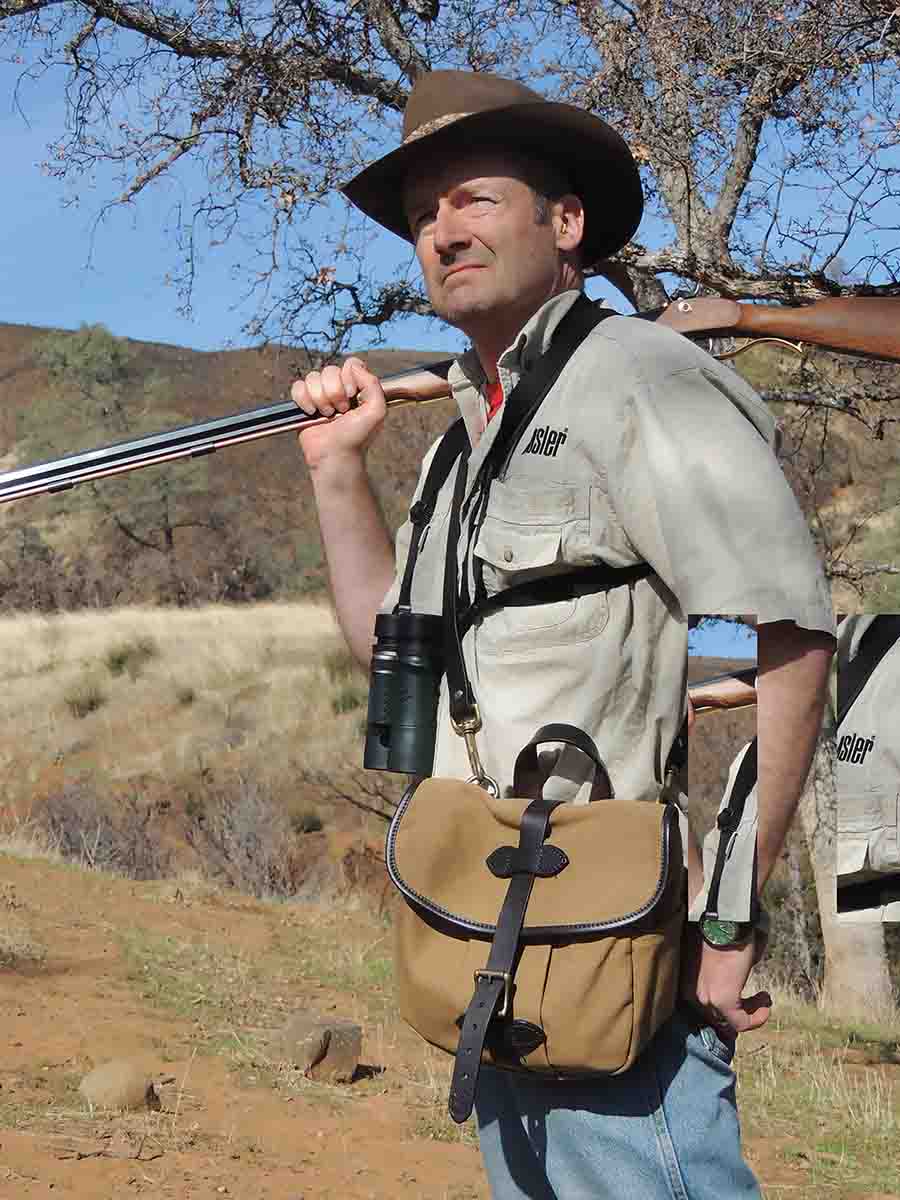

The area we hunted for wild boar in California had been swept by a forest fire less than two years prior. Tangles of burned-out trees, with new growth springing up around the charred trunks created an ideal habitat. After we took a couple of porkers and skinned them, we saw diggers in camp, on the woodpile and on the road.

Back at camp I had the gear packed, ready for the drive home when another squirrel showed itself, this one in the shade deep inside the limbs of a burned-out tree. With the front sight blade held low on the body, I squeezed.

When the smoke cleared, my prize was stretched out on the ground, done in by a shiny roundball.

The Case for a Smallbore Muzzleloader

There was a time when American long guns became downright economical. From the 1830s through the Civil War, hunters from places like Tennessee and Pennsylvania and Missouri relied on smallbore rifles.

Barreled for .32- or .36-caliber, a single-shot rifle could be used to good effect on red squirrels, feral hogs, wild turkeys, whitetail deer and for home defense. But when hunters found themselves west of the Mississippi, would-be trailblazers were woefully under-gunned.

Still, a lot of smallbore rifles went west because if a person was short on funds, shooting the smallbores was easier on the pocket book.

Another factor was probably the old dictum that the gun you know is better than the gun you don’t know. If you had a “thirty-two” that shot center every time, it might be hard to part with.

I ain’t parting with mine.

Named after David Crockett, the Crockett Rifle from Traditions is a .32-caliber half-stocked percussion rifle faithful to the game-getters carried in the 1830s and 1840s for small game back east and out on the frontier too.

The Traditions Crockett comes with a 31½-inch barrel rifled 1:48, a half-stock, brass hardware, a 30½-inch aluminum ramrod, a percussion lock and double-set triggers. Weighing in at 6¾ pounds, it is easy to carry, with a barrel-heavy heft coming up to shoulder. But the Crockett is not the only one of its type. Pedersoli builds .32-caliber Pennsylvania and Frontier models and Dixie’s Deluxe Cub is another .32-caliber option.

Loading for the Crockett

The Crockett wants to shoot well. With Triple 7, it pitches the roundball right where I want it. Belding’s ground squirrels (we call them sage rats) and California grey diggers are the regular quarry, but it could be a great option for cottontails, jack rabbits and coyotes coming to a call.

A friend of mine, Dan Egleston, from Grants Pass, Oregon, has put close to 700 rounds through his Crockett. He buys 0 buck in bulk, (0 buck measures out to .32 inch diameter) and patches with a thin square he cuts out of his old dress shirts.

When I checked the price, a person could order an 8-pound jar of 0 buck from Ballistic Products for $43.99 (00 buck is too big at a diameter of .33 inch).

My only complaint with the Crockett is I don’t like the aluminum ramrod. Egleston swapped his out in favor of a plastic unbreakable rod.

Plastic ramrods are periodically available from Dixie Gun Works. The Super Rod listed on its website goes for $16.25. One end is threaded for 10x32 accessories and the other for 8x32, and a total length of 411⁄8 inches. If a person could find one (they are not always readily available), the plastic rod could be cut down to fit.

Before talking to Egleston, I had only shot Hodgdon Triple 7 (a black-powder substitute) in my Crockett. I decided to take the Crockett to the range and shoot my favorite loads with black powder only.

At the Range

I can’t help but have preconceived notions about how things are going to work. It seems every other time I go to the range and really try to wring out a gun or a cartridge, I learn something new.

The first thing I saw was what looked like two bullet holes touching. I smiled. But then I looked around the target and found the eight-shot group was as big as a beach ball. I counted all the holes, some of them ragged, and realized the bullets were tumbling, key-holing in the paper, going in backwards and every which way.

I went back to shooting 20- and 30-grain charges with the hand-poured .31-inch diameter roundballs. To get a good sense of how the gun performed with real black powder, I shot groups with dry patches first, then with lubed patches.

On varmint hunts, this gun is a good choice when I expect to find the quarry between 10 and 30 yards. Its sights are primitive, but cut fine for precise shooting. For testing, I selected a small bullseye on a 1-inch grid and set the target at 25 yards.

Using a dry patch, the 25-yard groups with 20- and 30-grain charges averaged 2.25 and 2.5 inches. Lubing the patch improved the accuracy.

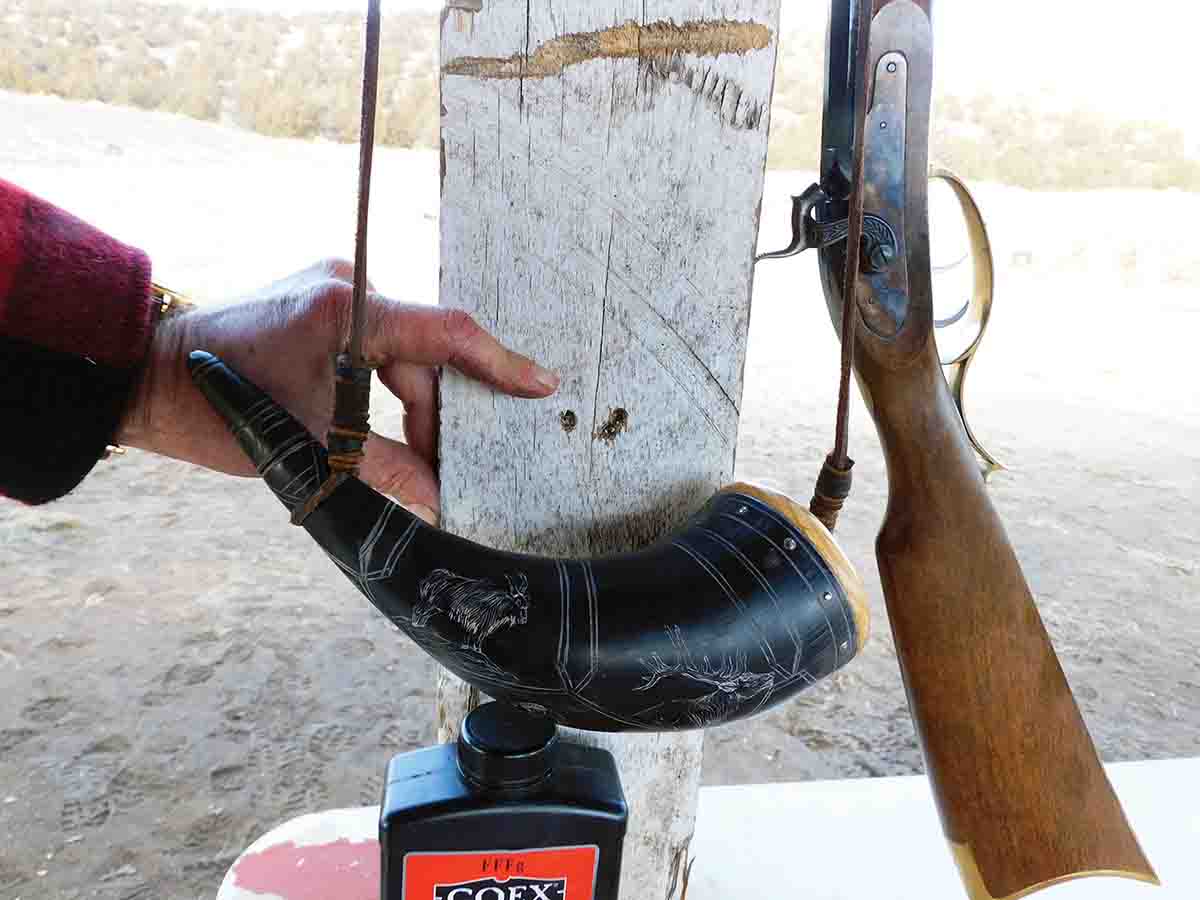

The most accurate load tested was with 30 grains of GOEX, the bear grease-lubed patch and .31-inch roundball with the best group measuring .80 inch.

I had been used to shooting Triple 7 powder, which cleans up easier than black powder, but I was surprised by the carbon buildup even while swabbing the barrel between groups. Fortunately, I had cleaning supplies with me and kept the barrel somewhat clean by wiping between shots. But after lubing patches and conicals with bear grease and pouring powder into the measure in the wind, my hands and the outside of the rifle got pretty grimy.

Cleaning the Rifle

A .30-caliber rifle cleaning kit can be used to clean the Crockett. I cut cleaning patches, put on latex gloves and got to work. Every black-powder shooter has their own system for cleaning up after a session at the range. Standard procedure is to take the barrel out of the rifle, remove the nipple with a wrench and then clean the nipple with soap and water and a pick. Next, I cleanup with soap and hot water and then run a patch or two with solvent and then run oiled patches. I might finish by wiping out the oil and then run a bear grease patch for storage. Often, I put a touch of anti-seize grease on the nipple before I seat it again.

Back to Boomtown

We were ankle deep in alfalfa, the ground beneath us tunneled and heaped. Under our boots a major metropolis of vermin. Above ground it was boomtown.

I slid the long, slender rifle out of its red, fringed flannel rug and measured 30 grains of Triple 7 into the barrel. Then I greased a patch, started the roundball and tamped it with the ramrod. I pinched a cap and slid it under the hammer. Shooting open sights, I’d have to be close.

A rat popped up from one hole and scampered down another. I looked at my friend and saw him purse his lips. He gave a quick chirp and the rat popped back up and exposed its head. I found the blade-front sight in the notch of the rear, clicked the trigger and stroked the set trigger.

Boom!

My friend figured it was a lucky shot. “Prove it,” he said. I proved it. Over and over.

We made a good team. He squeaked-up the rats and I put them down. For good. For the good of farm crops and alfalfa prices and the price of beef.

When the wind picked up, I held Kentucky windage and shot them. I could not miss. One shot I remember best. I had not missed with the Crockett Rifle and my buddies had noticed. A squirrel climbed out of its mound and stood up tall.

I had a roundball in the pipe and a cap under the hammer, and with a stiff crosswind, held 4 inches of Kentucky windage left and 3 inches of Tennessee high. With an economical puff of smoke, the Crockett spoke and another sage rat had made his final stand.

There were more rats to shoot. But I knew enough to pick up a different rifle while I had a perfect score. Shooting a muzzleloader is not the fastest way to clean up a boomtown.

* * *

Gary’s latest book is Bob Nosler Born Ballistic. For a signed copy, send $30 to Gary Lewis Outdoors, P.O. Box 1364, Bend, OR 97709. Contact Lewis at GaryLewisOutdoors.com.

Ruminations

Melting Down Fishing Weights

I learned how to cast my own lead roundballs from a couple of old-timers named Chisel and Finney. They in turn learned it from their father. In fact, it was their father I turned to when I couldn’t find .32-caliber roundballs in our local sporting goods store. “Chisel and Finney could teach you,” their old man said. Since the state doesn’t allow people their age to drive, I had to go across town to where Chisel (11) and Finney (9) already had the lead melting operation going full speed.

I put my offerings before them - old rifle and pistol bullets and a few used fishing weights. We turned the old lead into shiny new spheres and talked about critters and 1840s technology.

Lead shimmered in the pot at 622 degrees. Finney demonstrated how to pour the lead, how long to let it cool. Chisel showed me how to knock the balls out onto a damp cloth. Minutes later I was casting my own projectiles under the watchful eye of a 9-year-old and an 11-year-old.

When I shot my first squirrel with a roundball later that winter, I looked at the critter stretched out on the ground. I knew Chisel and Finney would have liked to have been there to see our handiwork in action. But they had to be in school.

.jpg)