Fifty Years with Remington's Sweet Seventeen

A Speedy Varmint Cartridge

feature By: Layne Simpson | April, 23

More successful creations included the 17 Hornet, the 17 Bee, the 17 Javelina on a shortened 222 Remington case, the 17-222 on the full-length 222 Remington case, the 17-223 on the 223 Remington case and the 17 Magnum on the 222 Remington Magnum case. Among the less practical were the 17-225 on the 225 Winchester case, the 17 Swift on the 220 Swift case and the 17 Super Magnum on the 22-250 case, the latter also a wildcat at the time. There were many more. Ackley, who was one of the best gunsmiths in the country, worked on several rifles for me. While visiting his shop in Salt Lake City, Utah, I asked him to mail me samples of any .17-caliber wildcats he had on hand. Expecting to receive a dozen or so, I was surprised to open the package and find more than 30 cartridges, some developed by Ackley, others by several of his acquaintances.

The cartridge with one of the most unforgettable names was the 17 Landis Rimless Super Eyebunger on the 25 Remington Rimless case. It was developed by Charles S. Landis who authored a couple of books in my library; Twenty-Two Caliber Varmint Rifles (1947), and Woodchucks and

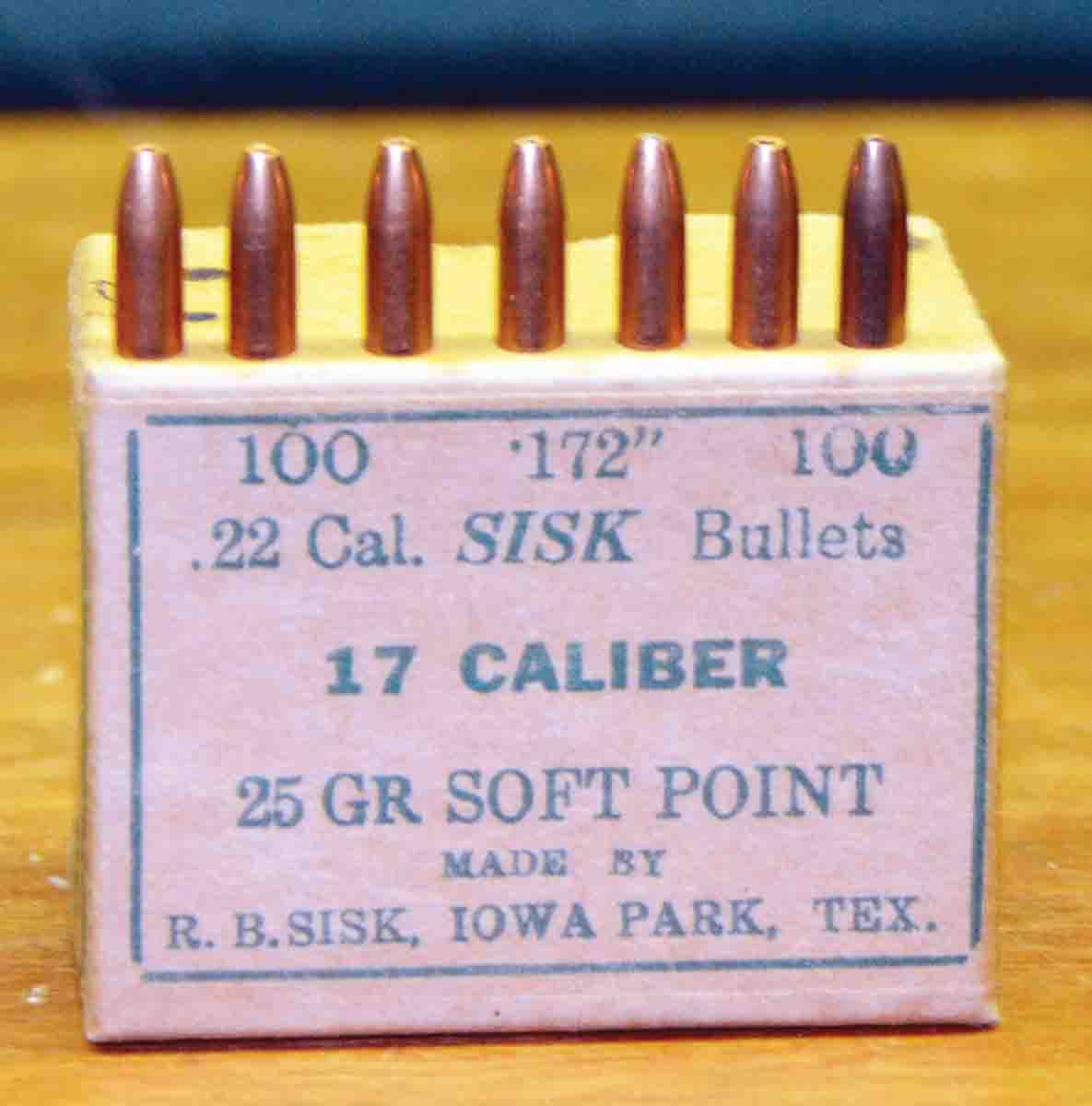

Charles Landis probably bumped off more woodchucks than anyone before or after his time. Young ones often ended up on kitchen tables, a custom I thought rather strange prior to living in Kentucky for several years where groundhog barbecues were not uncommon. As a varmint-shooting friend there mentioned, eating a grass-fed groundhog is much healthier than digesting store-bought beef steak loaded with all sorts of chemicals. Landis’ favorite cartridge, the 170 Landis Woodsman, was formed by necking-down the 22 R2 Lovell case that was an improved version of the 25-20 Winchester Single Shot case. The latter should not be confused with the shorter 25-20 WCF developed by Winchester for the Model 1892 lever-action rifle. Pushing a Sisk 25-grain bullet to 3,550 feet per second (fps), the 17 Woodsman was about 350 fps faster than the 17 Ackley Hornet of yesteryear and the 17 Hornady Hornet of today.

The most successful of the wild bunch was the 17 Mach IV offered by Las Vegas Gunsmith Vern O’Brien. Created in 1964 by Ackley and renamed by O’Brien, it was formed by necking down the Remington 221 Fireball case. O’Brien offered the 17 Mach IV in beautiful little rifles built around the very nice Sako L461 action. Barrels were made by Ackley and A&M Rifle Company and a very talented guy by the name of Nils Hultgren made the trim and nicely-figured walnut stocks. O’Brien Rifle Company advertisements occasionally appeared in various shooting publications, including Rifle, Handloader and American Rifleman.

Harrington & Richardson bought out Vern O’Brien in 1968 and introduced a commercial version of his rifle, which was also on the Sako L461 action. Called Model 317 Ultra Wildcat, it was chambered for the 17-223 formed by necking-down the 223 Remington case. The rifle was priced at $225 and while factory ammunition was never available, quite a few were sold to varmint shooters who handloaded their ammunition. At about the same time, Winslow Arms of Venice, Florida, began offering rifles chambered for the 17-222, 17-223 and 17-222 Magnum. Handmade .172-inch bullets were available from several small shops.

The big news for 1971 was Remington’s introduction of the 17 Remington cartridge. Finally, shooting a .17-caliber rifle

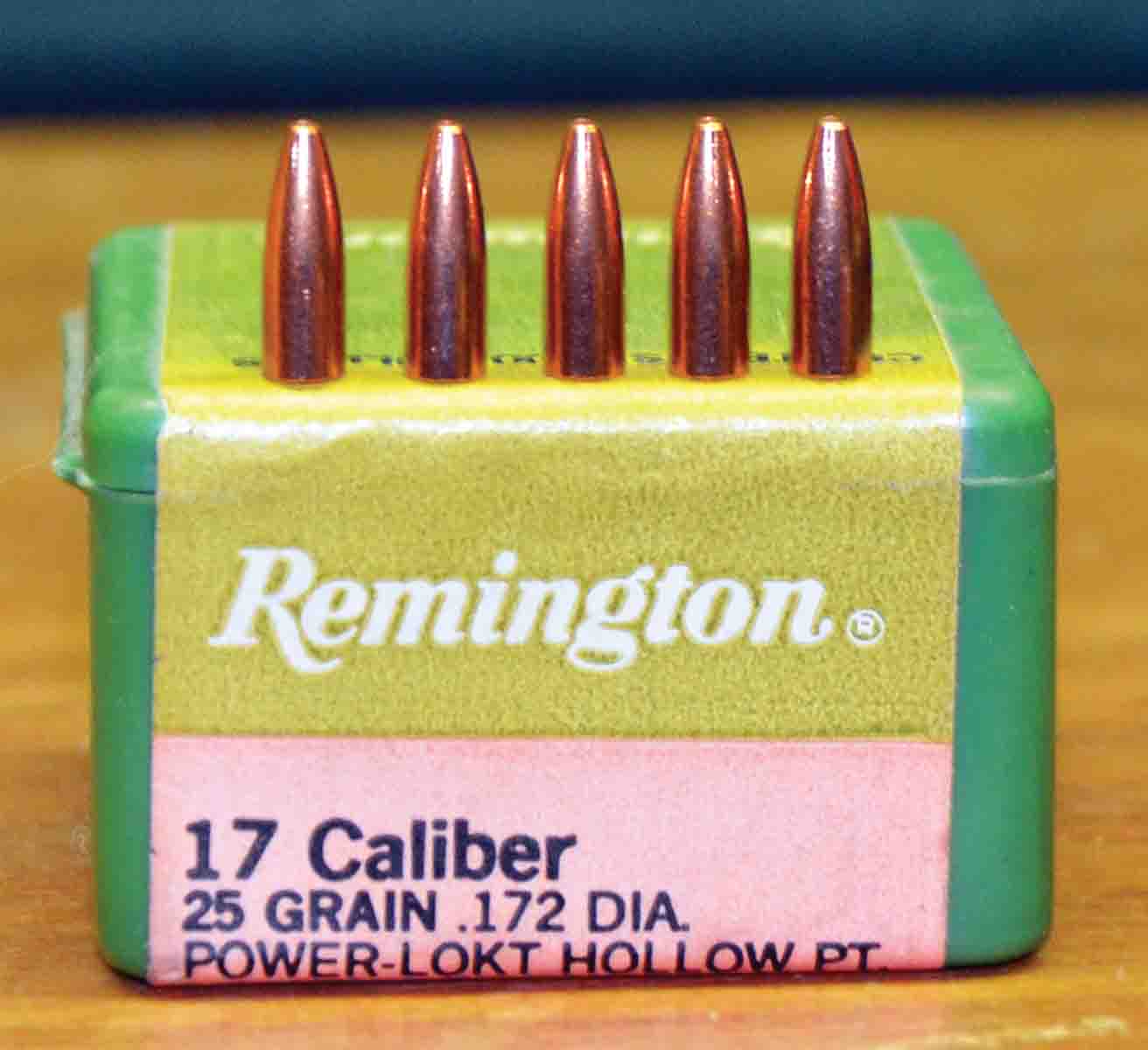

Remington’s speedster was loaded with a 25-grain Power-Lokt hollowpoint bullet at an advertised muzzle velocity of 4,020 fps. Loaded with 24 grains of what appeared to be IMR-4895, its “world’s fastest cartridge” billing was true among American manufacturers, because by that point in time, the 220 Swift loaded with a 48-grain bullet at 4,110 fps had not been available from Winchester for quite a few years. When zeroed 2 inches high at 100 yards, the 25-grain bullet of the new cartridge was said to strike about 2 inches above line of sight at 200 yards and 1.5 inches low at 300 yards where it delivered just over 300 foot-pounds of energy. The 17 Remington was introduced in the Remington Model 700 BDL with a 24-inch, stainless steel barrel of standard weight. The barrel was button-rifled with a 1:10 twist.

There was a time when shooting any .17-caliber cartridge was a pain in the posterior due to rapid buildup of bullet jacket fouling in the bore. Barrel makers had yet to master drilling, rifling and lapping such a small hole through a bar of steel. To make matters worse, some bullets were formed from extremely soft copper and that along with rough bores and lack of good equipment to clean them scared many shooters away.

The first consistently good .17- caliber barrels were those made by Remington, Shilen and Douglas. Those, along with better bullets, good cleaning rods and bronze bore brushes of the proper size, copper-dissolving solvents such as Barnes CR-10 and Sweets 7.62 have solved the bore-fouling problem. A top-quality Shilen barrel with a hand-lapped bore chambered for the 17 Remington requires cleaning about as often as barrels of equal quality in 22-250 and 220 Swift. Shilen still offers .17-caliber barrels with 1:10 and 1:9 rifling twist rates, the latter recommended for bullets longer than those weighing 30 grains. The Shilen Select Match Grade barrel on my Cooper rifle in 17 Remington has the 1:10 twist.

I bought a .17-caliber Model 700 in 1972 and by that time, the Remington 25-grain Power-Lokt bullet had become available for handloading, so I stocked up. It was as accurate as the Hornady bullet and did a better job of expanding at the outer fringes of practical distances for the cartridge. Hornady has since replaced the 25-grain hollowpoint with a V-MAX of the same weight and in addition to expanding at lower impact velocities, it shoots a bit flatter and delivers more down-range energy due to a 23 percent improvement in ballistic coefficient. It is also quite accurate. The 20-grain V-MAX is also quite good and while maximum loads start out 200 to 300 fps faster, the 25-grain version catches up at 200 yards and is moving about 100 fps faster at 300 yards.

Moving up in varmint size, I find the 17 Remington loaded with the Berger 30-grain hollowpoint at 3,800 fps to be quite effective on called-in foxes and coyotes. Berger used to offer more .17-caliber bullet options than any other company, but unfortunately, only the 25-grain FB Varmint is being produced at this time. I have enough of the 30-grain bullets to last awhile. I have never shot the 37-grain version because it requires a rifling twist rate no slower than 1:6 inches and as far as I know, Douglas is the only source for barrels with that twist rate.

As factory ammunition goes, Remington catalogs a 20-grain Accu-Tip-V at 4,250 fps. Hornady makes that bullet for Remington and it is nothing less than the V-MAX with a green tip. The 25-grain Power-Lokt bullet of yesteryear was formed by electroplating a jacket on a lead-alloy core, the same method used today by Speer to make Gold Dot bullets. It has been replaced by what is described by Remington as a Core-Lokt design. I find that rather odd since the Core-Lokt name has always been associated with bullets intended for use on big game. I would not faint from shock to learn that it is also made by Hornady.

Moving on to the Nosler website, I see Varmageddon ammunition with 20-grain solid-base tipped and solid base hollowpoint bullets at 4,200 fps. Like the two Remington loads, they are not easy to come by at this time. Possibly on the brighter side, the Hendershot’s Sporting Goods website promises two- to three-week delivery of custom 17 Remington ammunition loaded with the Berger 25-grain HP, the Hornady 20-grain and 25-grain V-MAX bullets and both Nosler 20-grain bullets.

I have long enjoyed shooting the 17 Remington will continue doing so because it is different and so much fun to shoot. Recoil energy generated by launching a 25-grain bullet at 4,000 fps for a 9-pound rifle is a mere 1.6 foot-pounds. Muzzle jump is so slight you can watch a distant varmint bite the dust right there inside your scope. The 17 Remington shoots as flat as the 220 Swift and milder muzzle blast makes it more suitable for use in settled areas of the country.

Years ago, a friend who worked at Remington, informed me that more Model 700 rifles in 17 Remington were shipped to Australia than to dealers in the United States with most sold to professional fox hunters. They prefer it because the little bullet punches a tiny entrance hole, wreaks havoc inside and seldom exits the opposite side, therefore pelt damage is minimal. I enjoy hunting Asiatic buffalo in Australia and each time I am there, friends remind me how much they love the 17 Remington for shooting small varmints. It remains surprisingly popular here as well.

.jpg)