Layne’s E.R. Shaw rifle in 22-250 has a 26-inch barrel with a 1:7 twist. It proved to be quite accurate with bullets ranging from 40 to 90 grains in weight. Its chamber was precision-reamed to SAAMI dimensions. Shaw describes the color of its laminated wood stock as “Nutmeg.”

The E.R. Shaw Mark VII rifle is on a blueprinted Savage 110 action.

Back in 1910, rifle designer and builder Charles Newton necked down the 25-35 Winchester case for a .228-inch bullet weighing 70 grains. After sending Newton a nice paycheck for his idea, Savage Arms introduced it in 1912 as the 22 High Power. During the three decades that followed, the cartridge sold quite a few Model 99 rifles. Not one to miss an opportunity to pick up a few more dollars, Newton developed another cartridge for Savage, and it was introduced in 1915 as the 250-3000 Savage. Soon thereafter, Newton necked down that case for the 70-grain bullet of the 22 High Power, but his luck had run out as Savage had no interest in another .22-caliber cartridge.

Soon after rifle designer and builder Charles Newton shortened the 30-06 case and necked it down for 257-inch bullets, Savage Arms introduced it in 1915 as the 250-3000 Savage. Newton then necked that case down for .228-inch bullets a about 15 years later, gunsmith Jerry Gebby loaded the Newton cartridge with bullets with a more common diameter of .224 inch and trademarked the cartridge it as the 22 Varminter. Remington tamed the wildcat in 1967 as the 22-250. Cartridges are 250 Savage (left) and 22-250 (right).

While visiting Newton in 1919, gunsmith Jerry Gebby spotted several of the cartridges on the 250 Savage case sitting on a shelf and took one home. Why he waited another 10 years before necking down a batch of 250 Savage cases for bullets with the more common diameter of .224 inch is lost in time, but in 1930, Gebby tasked friend and custom ammunition loader J. Bushnell Smith to load his cases with Sisk 55-grain bullets. Gebby wasted no time in building heavy-barrel rifles on 1903 Springfield actions chambered for the cartridge – one for himself, the other for Smith. The 250 Savage case has a shoulder angle of 26.5 degrees, and when necking it down, Gebby changed the shoulder angle to a slightly steeper 28 degrees.

The barrels of those first two rifles were stamped “22-250 Special,” but in an effort to discourage his competition from chambering rifles for the cartridge, Gebby changed the name to “22 Varminter” and had the name trademarked. His money was spent in vain. News of the cartridge and how easy it was to form by simply necking down the 250 Savage case quickly spread, and gunsmiths eased around Gebby’s trademark by stamping “22-250” on the barrels of rifles built for their customers. I began shooting the 22-250 when it was a wildcat, and due to the scarcity of 250 Savage cases, the custom rifle with a heavy barrel on a ’98 Mauser action came with two RCBS die sets. One set was for forming the case from unfired military-surplus 30-06 match brass, which at the time was both abundant and inexpensive. The other die set was for loading the cartridge.

The barrel of the Shaw rifle was threaded 5/8-24, and it came with a thread protector attached. This Nosler SR30 Ti suppressor did an excellent job of reducing muzzle blast.

A Redding Competition bullet seating die set and Type S sizing dies with interchangeable bushings was used for loading all ammunition for this project.

The 22-250 became extremely popular, and as incredible as it might seem today, Browning

As expected, 22-250 cases made by Lapua were extremely uniform and of excellent quality.

began chambering rifles built around the Sako action for it in 1963 while it was still a wildcat. That option first appeared in the rifles section of the 1964 Gun Digest, where the chambering was properly listed by Browning as “22-250 Wildcat.” When mentioning it on page 220, John Amber described the introduction by Browning as unprecedented due to the lack of factory-loaded ammunition. Browning offered it in the High-Power rifle with standard weight and heavy barrels. Then, in 1967, a company affectionately known as “Big Green” tamed the old wildcat, called it the 22-250 Remington and began loading the ammunition and chambering very accurate rifles for it. At the time, Phyllis and I were living in Kentucky, and since coyotes had yet to arrive in that part of the country, groundhogs were quite abundant. A friend there bought the first Model 700 BDL Varmint with a heavy 24-inch barrel in 22-250 to show up at a local gun shop. I was shooting an extremely accurate Remington 40X in 220 Swift, and had to work hard to keep up with my friend and his equally accurate Model 700 in 22-250.

Shown here are three of many powders that are excellent choices for loading the 22-250 with bullets of various weights.

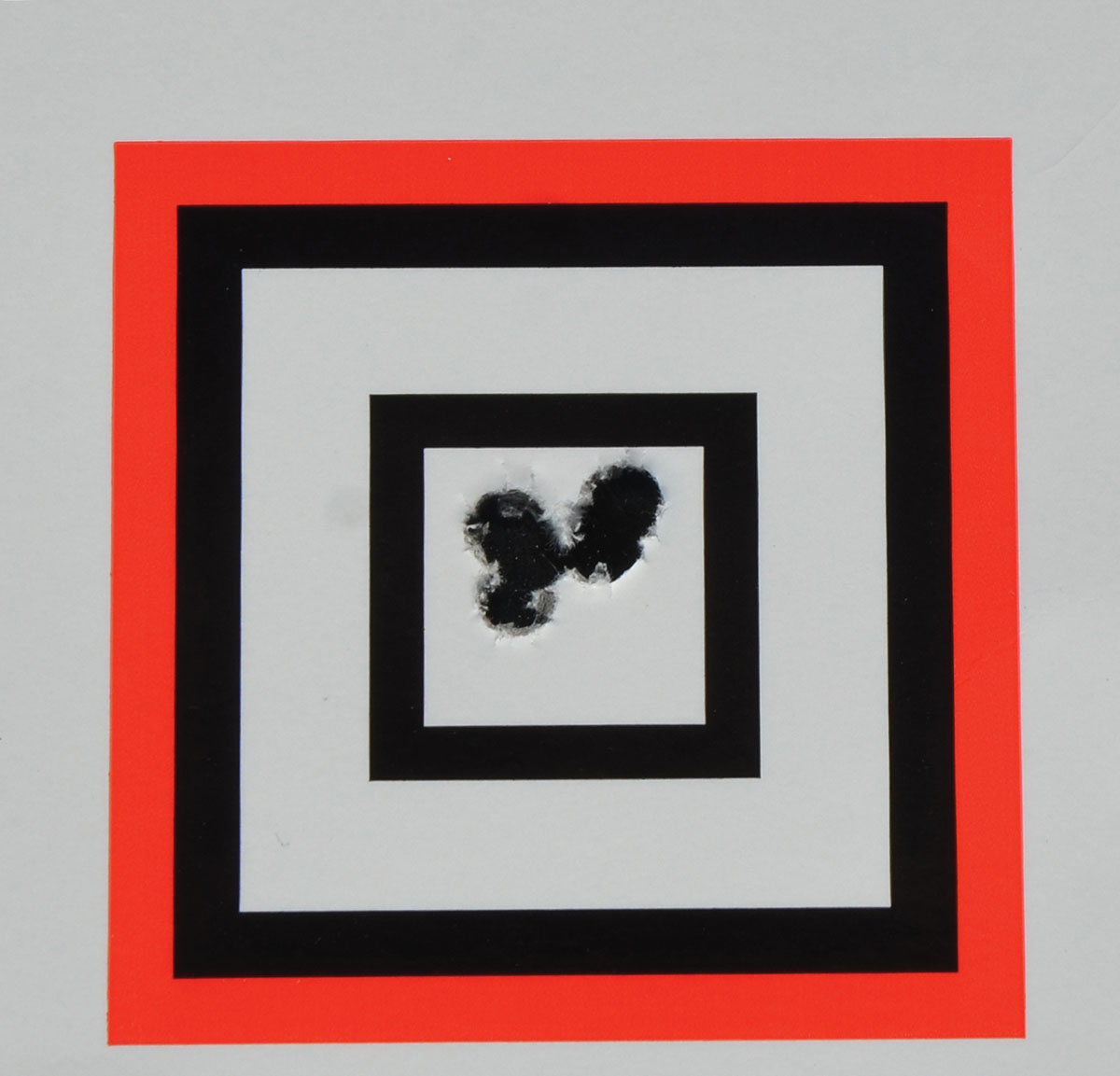

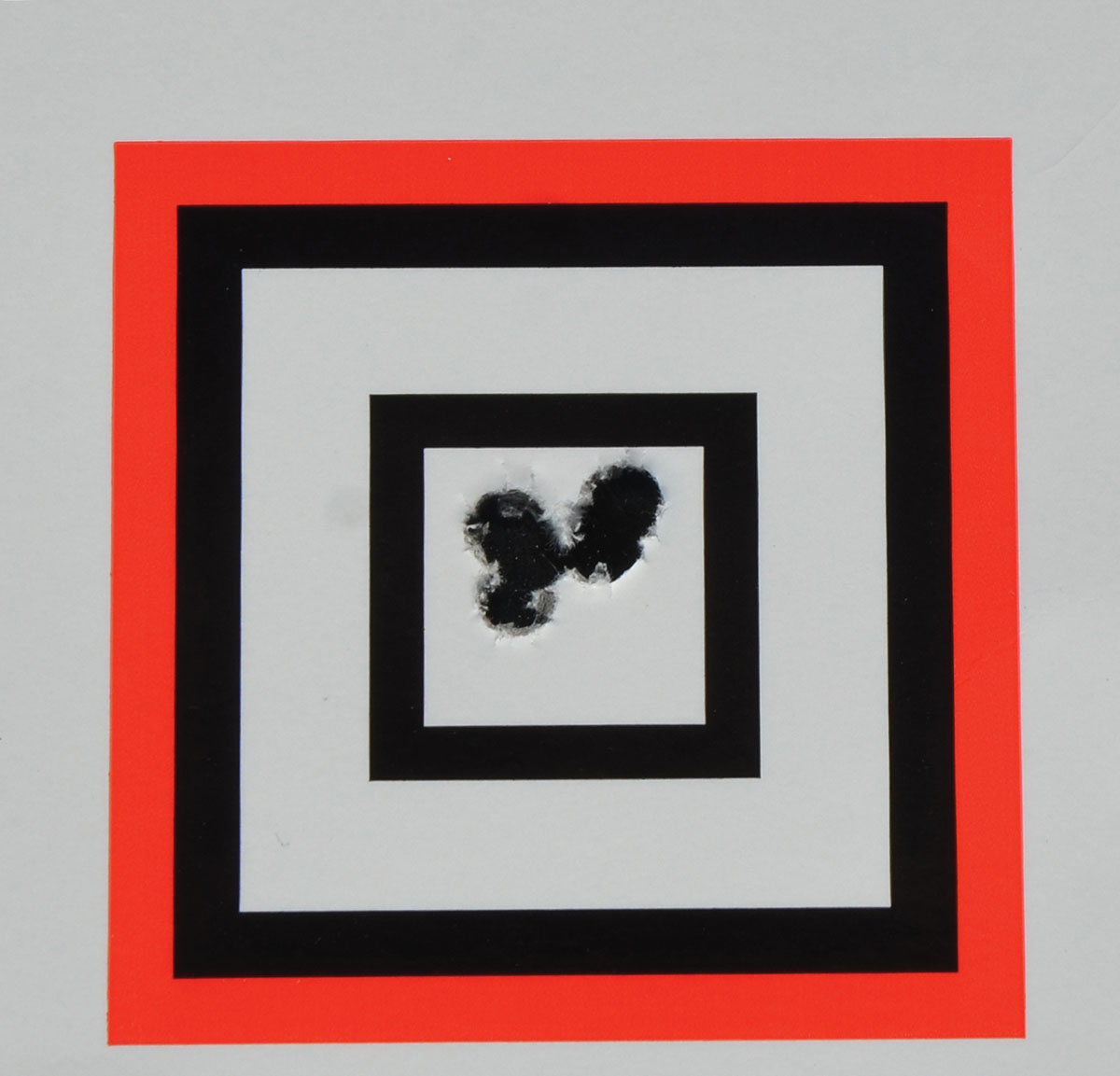

As proven by the Shaw Mark VII rifle, a good barrel with a 1:7 twist can deliver excellent accuracy with bullets weighing from 40 to 90 grains.

For many years, the standard bullet weight range for the 22-250 was 40 to 55 grains, and just about everybody was happy in varmint country. Then came the Nosler 60-grain Ballistic Tip, followed sometime thereafter by the Hornady V-MAX of the same weight. While some rifles shot them quite accurately, accuracy left a bit to be desired in other rifles simply because the standard 1:14 barrel twist rate bordered on being too slow. Then, .224-inch bullets got even longer. In support of across-the-course High-Power competitors who were transitioning from .30-caliber MIA rifles to AR-15s with quick-twist barrels during the 1990s, Berger introduced extremely accurate, high ballistic coefficient bullets weighing up to 90 grains. Palma and Fullbore competitors, who also were experimenting with various .22-caliber cartridges, also welcomed the new finger-long projectiles. Nosler soon joined the chase with match-grade bullets weighing 69, 77, and 80 grains and published data for them in the 223 Remington, 5.56mm NATO and the 22-250 in various reloading manuals. The earliest I have with that data was published in 2012 and the latest Nosler manual also has it. That data also benefited those who were dissatisfied with the accuracy of Nosler’s 60-grain Partition and Ballistic Tip bullets in their 1:14 twist rifles. The rifling twist rates of the company’s test barrels for bullets weighing from 60 to 80 grains was 1:8.

My Mark VII rifle with a quick-twist barrel in 22-250 was built by custom shop craftsmen at E.R. Shaw, a company long known for making excellent barrels. Made by Savage Arms to Shaw’s specifications, the action is blueprinted at the Bridgeville, Pennsylvania, factory prior to being fitted with a barrel. Shaw greatly improves the Savage AccuTrigger with a process described as triple-honing of all engagement surfaces. The pull weight on my rifle was easily adjusted to 30 ounces with no creep or overtravel. When placing my order, I specified a 26-inch, stainless-steel barrel with a light varmint contour, and since I wanted to experiment with the Berger 90-grain VLD Target, I chose a 1:7 rifling twist. Barrel diameters are 1.250 inches at the receiver and 0.720 inch at the muzzle, heavy enough for excellent accuracy while being light enough to carry over hill and dale during day-long treks on varmint shoots.

I would be shooting the rifle with a Nosler SR-30ALTi suppressor and specified 5/8x24 threads. The barreled action was hand-bedded in Shaw’s special laminated wood stock in a color described as Nutmeg and the barrel free-floated. My digital postal scale indicated a weight of 8 pounds, 10 ounces. For accuracy testing and varmint shooting, the rifle usually has a Bushnell 6-24X Engage scope held in place by Weaver 30mm six-screw rings and a Talley Picatinny rail. When occasionally traveling a bit lighter, I switch to a Nightforce SHV 3-10X, also with a 30mm tube. Both are excellent scopes.

This five-shot group, fired at 100 yards with the Hornady 40-grain V-MAX pushed to 4,050 fps by RL-15, measured .346 inch.

With the exception of several wildcat cartridges, all chambers are reamed by Shaw to exact S.A.A.M.I. dimensions. As popular opinion has it, due to the short throat of the 22-250 chamber, heavy (long) bullets have to be seated quite deeply into the powder cavity of the case. While this is true of some bullets of older designs, it does not hold true for more modern bullets with sleek shapes and extremely long ogives that can be seated farther out of the case. When the Berger 90-grain VLD Target is seated to a cartridge length of 2.700 inches, its base rests adjacent to the body-shoulder juncture of the case. At that cartridge length, bullet free-travel prior to rifling engagement is .020 inch.

It is important to keep in mind that 22-250 rifles with the standard 1:14 rifling twist may not stabilize pointed bullets much longer than those weighing 55 grains. More specifically, a bullet measuring much longer than .810 inch may not be stable in flight. They include, but are not limited to, those weighing 60 grains and heavier made by Berger, Nosler, Hornady and others. The slowest twist rates recommended by Swift for the 62-grain and 75-grain Scirocco II bullets are 1:9 and 1:8, respectively. The respective lengths of those bullets are .950 inch and 1.075 inches. The Berger 90-grain VLD

This five-shot group, fired at 100 yards with the Berger 90-grain VLD Target pushed just beyond 3,000 fps, measured .302 inch.

Target measures 1.252 inches. My advice is to go with a 1:7 twist and have all bullet weights covered. Lightweight thin-jacketed bullets such as the 1950s vintage Hornady 50-grain and 55-grain SX will likely come apart when subjected to the increase in centrifugal force and fail to reach the target. In my experience, V-MAX bullets from that company, as well as Nosler Ballistic Tips of various weights can withstand the strain and deliver excellent accuracy as well.

Equally important is the fact that actual chamber dimensions of rifles chambered for the 22-250, or any other cartridge for that matter, can vary slightly from SAAMI-specified dimensions. For this reason, the chamber throat of a rifle may or may not be long enough to accept the heavier (longer) bullets. The chamber throat of my Shaw rifle is long enough to handle bullets as long as the Berger 90-grain VLD Target when seated in the case for .020 inch of jump prior to rifling engagement. I have several other rifles in 22-250, one is a B78 single shot built by Browning during the late 1970s. Another is a Remington Model 700 built about 20 years later. Neither rifle has been shot a lot, and their chamber throat lengths are quite close to the same as for my Shaw rifle. Even so, the 1:14 rifling twist in the barrels of those rifles rules out the use of bullets heavier (longer) than 55 grains.

While this report has mostly been aimed at varmints, where legal and at reasonable distances, the 22-250 can be very effective on whitetail deer and pronghorn antelope, and for that, the Nosler 60-grain Partition, Swift 62-grain Scirocco II, Swift 75-grain Scirocco II and Hornady 80-grain ELD-X exiting the muzzle at maximum speed would be extremely effective.

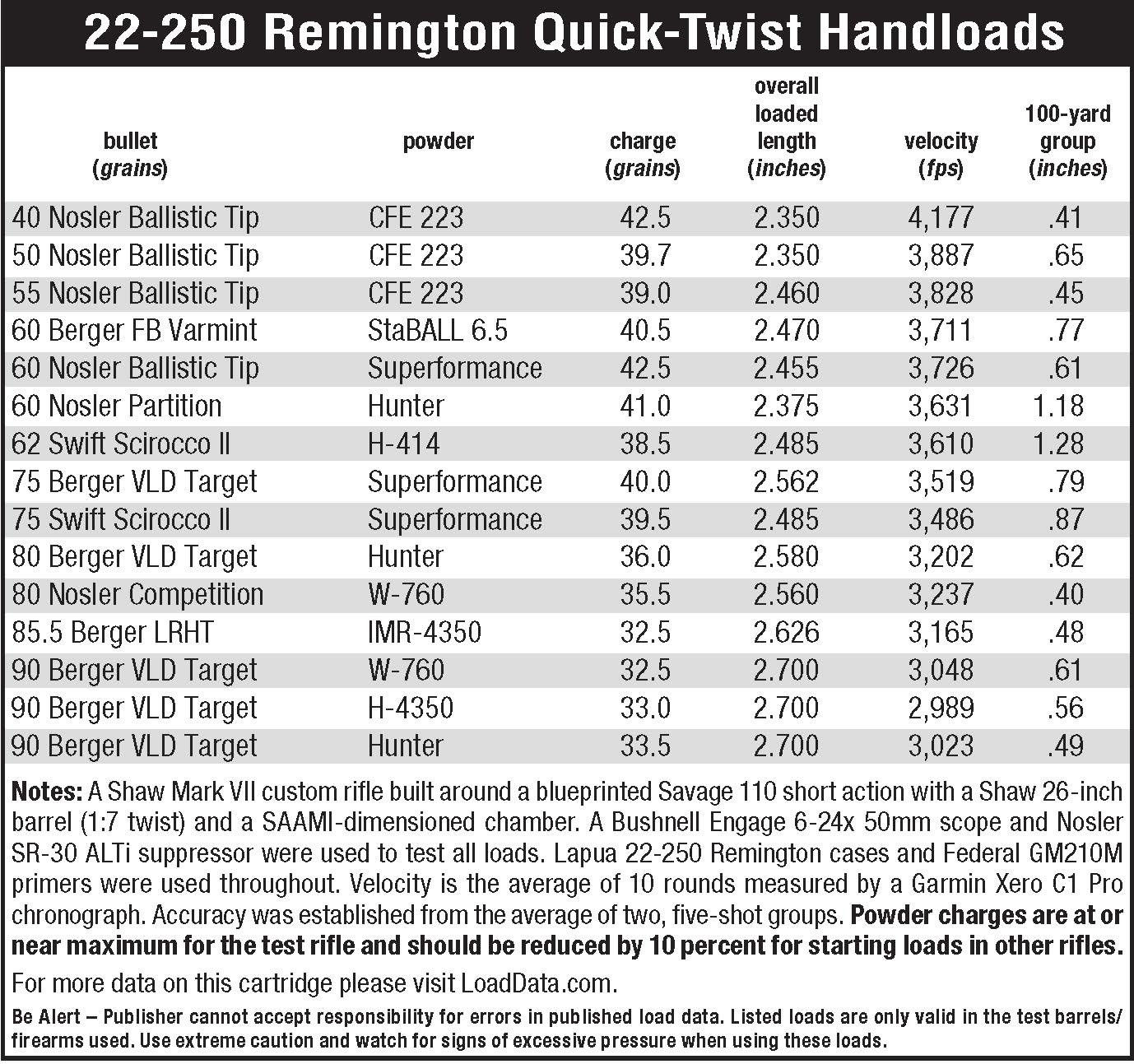

When putting together test loads for the Shaw Mark VII rifle, I used a Redding die set. Powder charges were thrown with a Redding Competition PR-50 measure, and bullets were seated with Redding’s Competition die with the precision-ground alignment sleeve and floating seating stem system. At the bench, the rifle was snuggled into a Brownells leather bunny-ear sandbag at the rear and a Lyman Match Shooting Bag resting on that company’s quick-adjust Bag Jack at the front. Graham wind flags were used. It should also be noted that the powder charge weights listed in my test results chart were maximum or close to it in the test rifle and should be reduced by 10 percent for starting loads in other rifles. The ambient temperature during my testing reached 106 degrees Fahrenheit, and the barrel was water-cooled after every five shots.