Tackling the 20 Practical

Black Gold Custom Arms MT-15

feature By: Rob Behr | April, 20

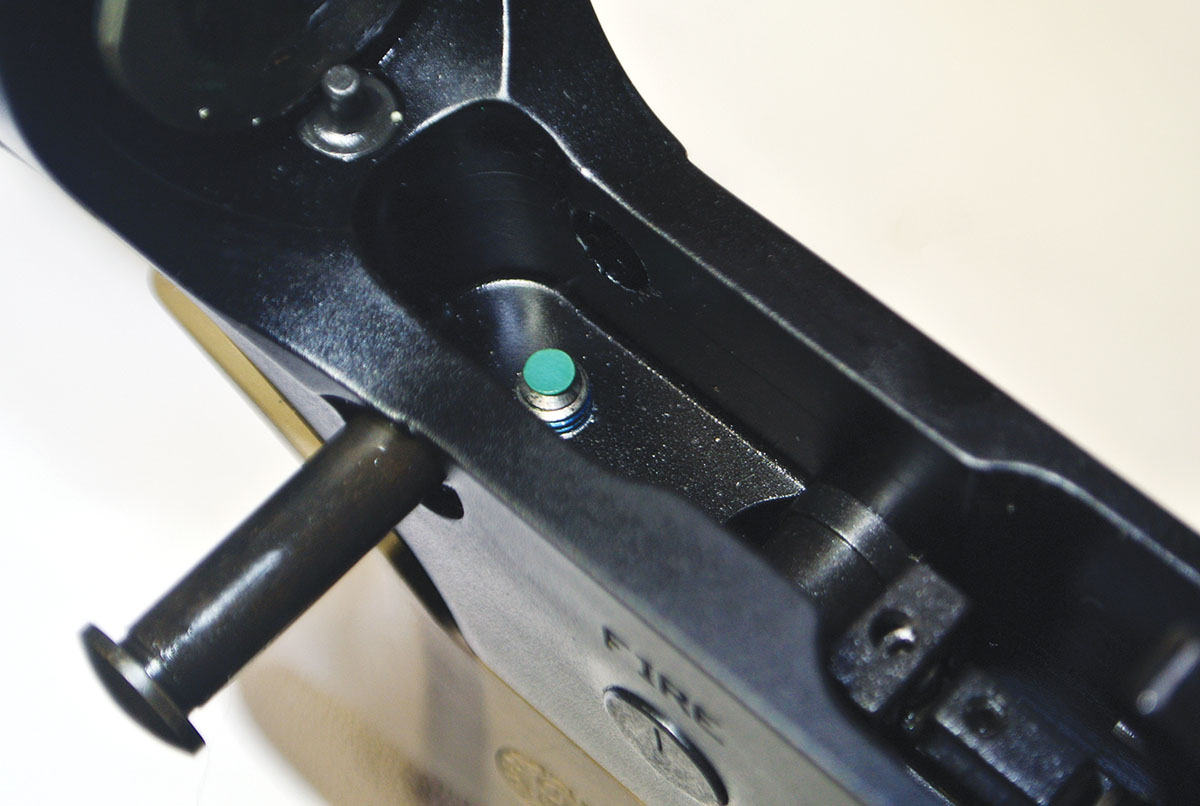

One of the common complaints against the AR-15 design began soon after it saw combat in the Vietnam War. There was no way to directly manipulate the bolt. America’s previous self-loading battle rifles used charging handles that were part of the bolt assembly. As a result, an energetic slamming with the palm of a hand could force the action closed or open in the event of a jam. The government’s answer to this problem was the addition of a forward assist button that cams the bolt forward mechanically. In the real world it often makes a jam worse. Unsticking a jam still relies on the rifle’s tenuous charging handle, which often does not provide enough leverage to remove truly stuck cases.

The rifle’s heavy barrel contour uses a .936-inch gas block and measures 24 inches from the top of the large muzzle brake to the breechface. It uses a 1:10 twist. Providing the interface between the shooter and the barrel is a free-floating forearm made by Seekins Precision. Designated the SP3Rv3 Rail System, it features a smooth, flat bottom created to promote better accuracy while shooting from bags. It is an ideal choice for an AR-15 that will be used for varmint hunting. The fully adjustable Luth- AR Modular Buttstock Assembly was surprisingly sturdy and held adjustments well. Running the show is a Geissele Hi-Speed National Match trigger that is tuned with that company’s Match Spring Set for a release weight of 1.9 pounds.

The MT-15 was fitted with a Nightforce NXS 5.5-22x 56mm scope, one of the finest second focal plane optics available. With .25-MOA adjustments and a MOAR reticle, which is designed for quick target ranging in the field, the NXS is an ideal scope for long-range varminting.

Several steps are required to create safe loads for a wildcat. They are more challenging than simply reading data out of a book and considerably more interesting. There is also one cardinal rule that many wildcatters seem to forget: There is no such thing as a free lunch. Fantastic velocities, without significant increases in case volume, are driven by equally fantastic pressures. Above all else, common sense is required to be a safe wildcat handloader.

It’s best to form cases using new brass. New cases from the same lot will resize more easily and provide more consistent neck tension than will mixed range brass.

With the 223 decapping unit removed, set the bushing die for normal full-length resizing. Drop the .236-inch bushing, numbered side down, into the die and size the case. Mild lubricant on the neck is good here, but too much will make trouble. There is actually very little sizing being done if you are beginning with new brass. Once all of the brass has been sized, remove the .236-inch bushing and replace it with the .226-inch diameter bushing. Add the 204 Ruger decapping assembly to the bushing die and resize all of the cases again. With that, the case is ready for loading. Reloading the fired cases only requires a pass through the resizing die with the .226-inch bushing and 204 decapping assembly in place. The 20 Practical is a very friendly wildcat.

It is best to deal with a wildcat the same way a ballistics lab deals with new production cartridges. The first consideration is the wildcat’s case capacity. This is typically expressed as grains of water to overflow. The easiest way to find this volume is to weigh a number of sized cases and then carefully fill them to the rim with distilled water. Once filled, the cases are weighed again. Subtracting the empty weight from the filled weight of each case gives a reliable average case volume. The five 20 Practical cases measured in this manner produced an average of 29.4 grains.

The 20 Practical uses a smaller bore diameter than its parent case, the 223 Remington, but not so radically different that it cannot share burn rates with the parent case. What is indicated by this shift to a smaller diameter is that slower powders appropriate to the 223 Remington may prove to be better performers in the 20 Practical.

A chronograph is an absolutely indispensable tool for handloaders working with wildcats. They are the least expensive and most readily available tool to estimate load pressures. They allow this insight into internal ballistics because of the pressure-to-velocity ratio that is so important to manufacturers of canister grade propellants. Ballistics labs test new lots of powder against known samples with idealized burn rates to compare both velocity and pressure. Only small shifts are allowed in either variable, which promotes lot-to-lot consistency. Some shifts must be expected, but the numbers are consistent enough to allow handloaders to read and understand pressures by using chronographed results. Lower than anticipated velocity, given a similar barrel length, indicates a higher charge mass can be applied until the published velocity has been achieved. Conversely, higher than expected maximum velocity indicates that the charges should be lowered. In canister-grade products, pressure and velocity operate in lockstep. Once the velocity has been achieved, so has the predicted pressure.

The 20 Tactical is also based on a necked down 223 Remington and as a bonus, it is popular enough to have some published pressure data. Outwardly, the 20 Tactical mimics the longer neck of a 222 Remington and uses a 30-degree shoulder rather than the 23-degree shoulder of the 20 Practical. This is why knowing the grains of water capacity is so important. Variations in capacity can create unexpected pressure issues even if the cartridges are very similar. The ballistics software package QuickLOAD shows that the 20 Tactical holds 29 grains of water, close enough to make its data a good starting point for 20 Practical load development.

Both Hodgdon and Western Powders have pressure tested data for the 20 Tactical. Hodgdon’s data was created using the SAAMI 55,000 psi maximum pressure limitation set for the 223 Remington. Western Powders’ data was created using the CIP (Commission Internationale Permanente, the European governing body regarding firearms and cartridges) pressure maximum for the 223 Remington, which is 62,366 psi. Either standard is reasonable, but 62,000 psi provides noticeably higher velocities.

Knowing that the pressure/velocity ratio acts as a kind of speed limit for predicting pressure, studying the published data helps to set practical velocity limitations for initial testing. Hodgdon’s data is a bit dated, providing only data for the now discontinued Hornady 33-grain V-MAX and Berger 36-grain bullets, but it is still useful.

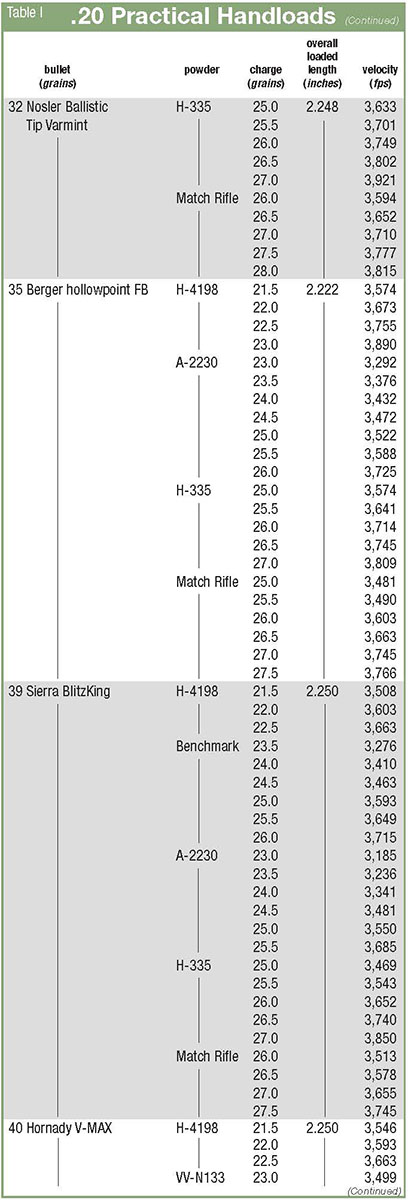

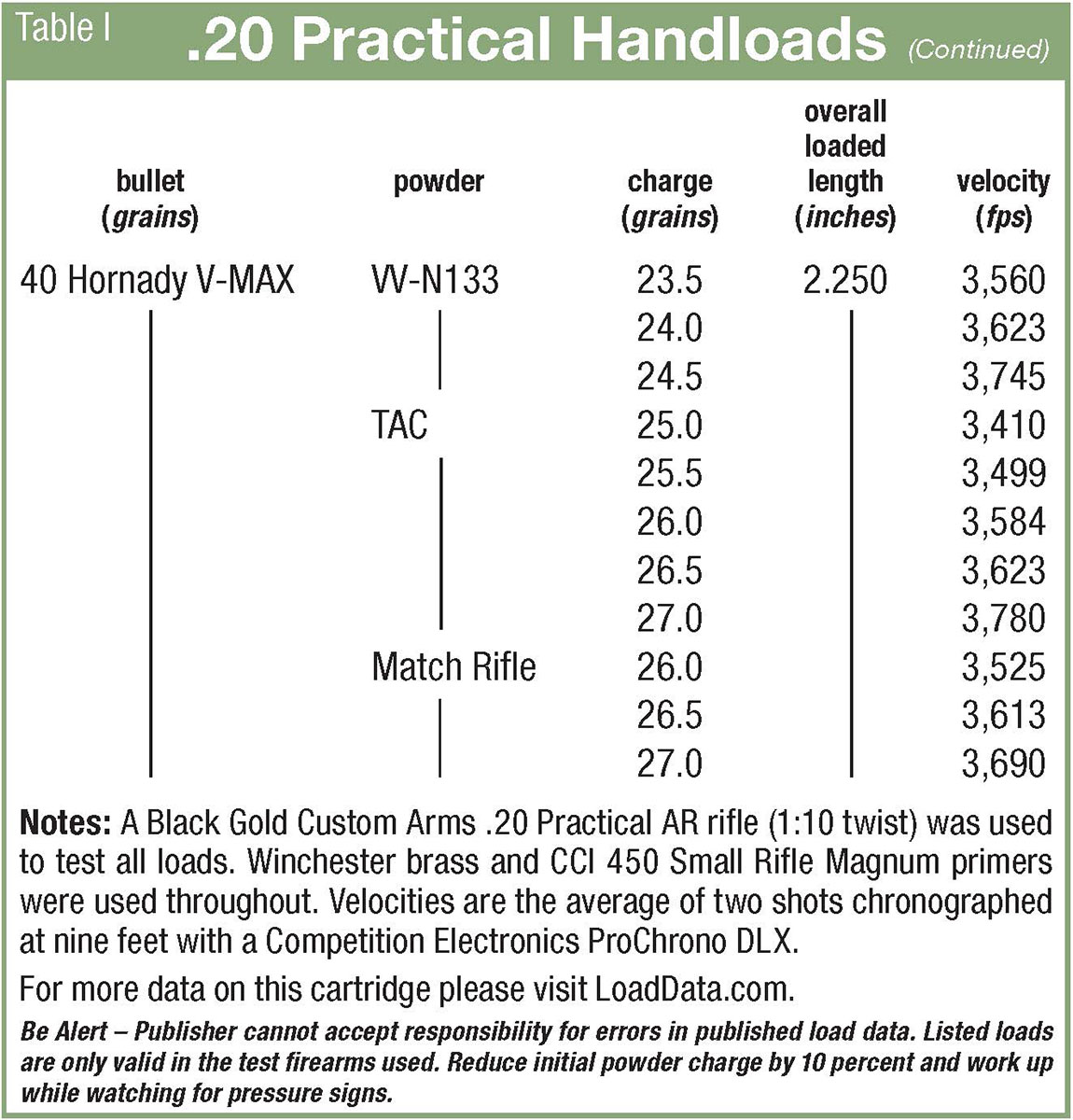

Table I reflects the ladder testing results. The idea is to begin with a known low load and work just beyond the anticipated desired maximum case pressure. There is a point of diminishing returns here in terms of round counts for this type of testing. In this instance, two rounds were fired to establish the velocity average because I didn’t want to have to return Dave’s rifle by ringing his doorbell and then running away. The name of the game in varminting is accuracy and velocity. The ladder testing was only needed to access the highest reasonable velocities for each powder. Testing for accuracy was done regressively, starting with the highest velocity and worked backward until accurate combinations were found.

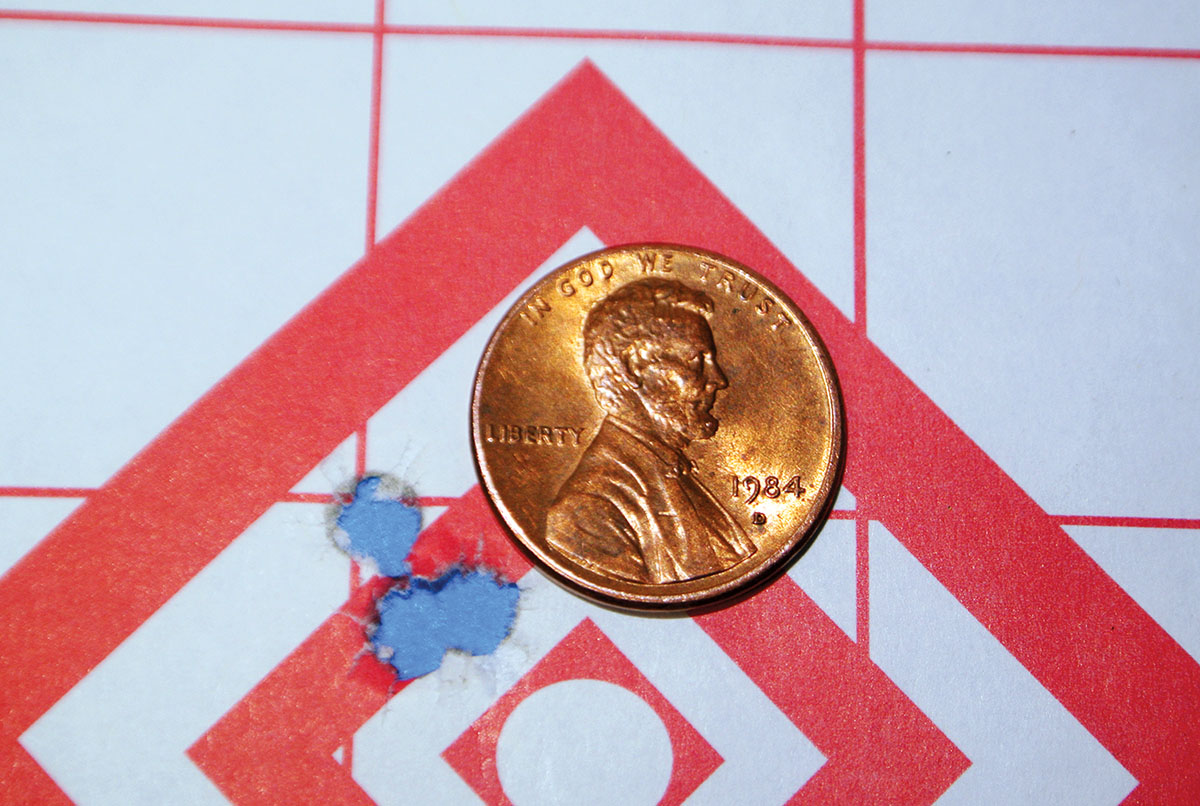

The most accurate powder and bullet combinations are shown in Table II. Accurate loads came easily with the MT-15. Four of the six bullets tested were either near or under a .5 MOA. The 40-grain V-MAX did not lag far behind. The exception proved to be the 24-grain Hornady NTX bullet. It was absolute Kryptonite for the MT-15 and no tested powder turned in varmint-grade accuracy. It is neither the fault of the rifle or bullet. Some combinations just don’t work out.

The 20 Practical is an easy wildcat to form, and once that initial step has been completed, it’s no different than any other cartridge to reload. No, Dave, don’t rechamber it. Your MT-15 is perfect just the way it is.