The Swift Mystique

The Phenom Is Still a Phenom

feature By: Terry Wieland | October, 23

It has everything: Heroes, villains, outright lies and counterclaims, big companies versus the little guy. We don’t have enough space to tell the whole story, but here’s a summary.

Created by Winchester for its bolt-action Model 54 in 1935, the Swift launched a 48-grain bullet at the unheard-of velocity of 4,110 feet per second (fps). It was the first cartridge to break the 4,000 fps barrier in factory ammunition and remained the only one to reach that level for many years. Even today, it’s a rare cartridge that goes faster.

The Swift was so far ahead of its time that it took years to sort out all the problems associated with it, including barrel steels, twist rates, bullet construction and cuprous fouling. But the few who did get to know the Swift and understood it, formed an exclusive clique that endures to this day. There are the Swift shooters, and then there are all the others.

The Swift’s career is a puzzling and sometimes sordid tale of premature demise and partial resurrection. There are some genuine technical problems at the root, compounded by personal and professional jealousy, with accusations published and then repeated over and over, down through the years.

In the 1930s, interest in varmint shooting and 22-caliber centerfires was just getting started. Experimenters were wildcatting hotshot 22s and Winchester wanted in on it. It went to work designing the ultimate 22 centerfire, and did so by beefing up and necking down, the old 6mm Lee Navy semi-rimmed case.

They called it the Swift, a neat double entendre given its muzzle velocity of 4,110 fps with a 48-grain bullet. The new creation was swift, indeed!

The design was a surprise, particularly to some prominent wildcatters who had necked down the 250 Savage to 22, called it the Varminter, and expected Winchester to take their advice and legitimize it as Winchester’s new hotshot. Their disappointment manifested itself in a campaign criticizing the Swift for every conceivable failing.

The most prominent Swift shooter I know is Jim Carmichel, long-time shooting editor of Outdoor Life. (Carmichel was also an early writer for Rifle and Handloader.) In the early 1970s, he undertook thoroughly researching the Swift’s career, scouring old magazines beginning in the 1930s. He gave a complete account in his 1975 book, The Modern Rifle.

The first criticism was that it burned out barrels, and in the mild steel barrels of the Model 54, this had substance. When these were replaced with better chrome-moly alloys and the post-war stainless barrels in the Model 70, it ceased to be a problem. Yet the charge was repeated endlessly.

There were also problems early on with rifling twist rates, bore diameters and bullet construction. At the time, the most popular 22 centerfire was the 22 Hornet, which used bullets of .223 diameter, with thin jackets, and a twist rate of 1:16. Dazzled by the Swift’s ballistics, gunsmiths began building custom rifles, often using barrels intended for the Hornet, or even 22 Long Rifle, which were both soft and undersized. Naturally, serious problems ensued.

By the early 1950s, Winchester itself went to stainless barrels in .224 diameter, with a twist rate of 1:14. By that time, however, disappointing results with many custom rifles resulted in more bad press, which eventually just fed on itself.

Another criticism, that the Swift could not be loaded down, has been dispelled long since by handloading experts such as Ken Waters, who covered the cartridge in two Handloader “Pet Loads” articles (September 1978, and June 2000), both of which are included in the massive Pet Loads anthology available from Wolfe Publishing.

A final problem did not get covered in the 1950s, but undoubtedly existed: Cuprous fouling. This was little understood in those days, but was a serious problem and largely accounts for accusations that Swift accuracy falls off quickly. At those velocities, you will get a cuprous build-up, and if you don’t clean it out, accuracy will suffer. Carmichel wrote that, with one exception, every rifle that came to him, supposedly “burnt out,” was returned to fine accuracy by a thorough cleaning.

But the Swift refused to die. In 1972, Carmichel and Gun Digest Editor John T. Amber prevailed upon Bill Ruger to chamber a limited edition of the Model 77 for the Swift. It proved so popular, it was added as a standard chambering, and later, also chambered in the Savage Model 112V. Remington finally joined the group, chambering it for a while in the Model 700.

Since that time, factory chamberings and ammunition have come, gone, and come again. Hornady offers loaded ammunition, and Nosler makes brass. Since the Swift has always been primarily a handloader’s cartridge, however, availability of factory loads is a minor consideration.

My own experience with the Swift is thin. I first encountered it in 1996, on a visit to Dakota Arms. I was prairie dog shooting and, with Don Allen spotting, killed one at a measured 535 yards – the longest shot I have ever made on a game animal. When I reluctantly returned the Swift and turned to a 223, I felt like I’d stepped out of an Aston Martin and into a Ford Fairlane.

At the time, I had two friends in Canada who were devoted Swifties, dedicated woodchuck hunters, serious handloaders, and benchrest shooters and they regarded all other 22-caliber centerfires with contempt. After my South Dakota experience, I would have acquired a Swift if I could. None were available, but the seed was planted. Early this year, I came across four dusty boxes of Remington factory ammunition, grabbed it for 20 bucks a box, and began seriously searching.

No custom maker was interested in chambering a Swift, but out of nowhere appeared a pre-’64 Model 70 in near-pristine condition at a Rock Island auction.

The rifles from the early 1950s are the sweet spot of Model 70 collecting in terms of overall quality and workmanship, and in the case of a 1953 Swift, they are as good as it gets.

It has a stainless 26-inch barrel with a bore that looked virtually unfired. I was surprised by this until I learned that, after it was discontinued, Winchester collectors bought up every one they could find and hoarded them. At a later auction, six almost identical Swifts were offered, and all sold for about what I paid – a little over $2,000. They had obviously emerged from a collection and been used very little, if at all.

Even if a bore looked bad, however, I would take a chance and hope a thorough cleaning would do the trick. It would be worth the gamble.

In spite of the scare stories, there is nothing mysterious or difficult about loading the Swift. Proper case preparation, and keeping them trimmed, is all that’s required. It’s a high-pressure cartridge, of course, so when you are working at the upper end, it’s essential to watch your loads. But there is no evidence that it’s unusually sensitive to slight changes in powder weights.

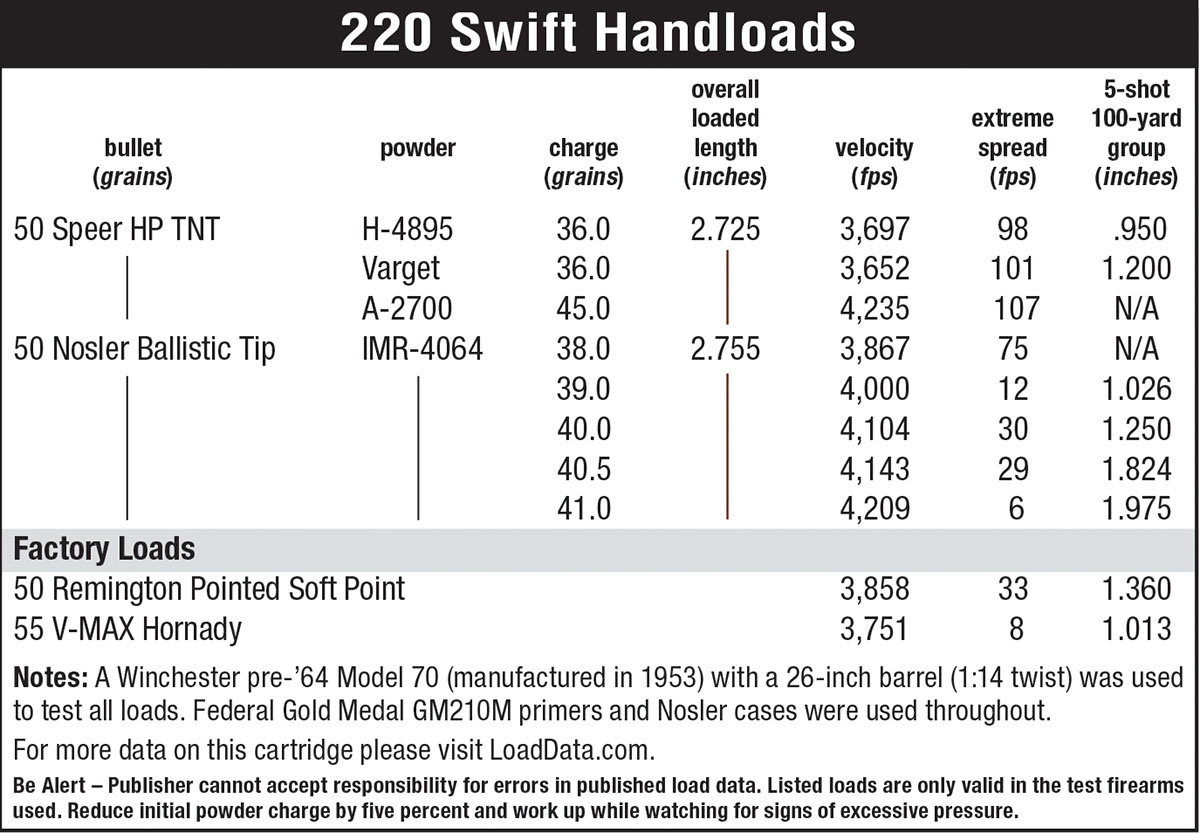

Since its inception, the best powder for the 220 Swift has been IMR-4064, which was introduced shortly after the Swift itself, in the 1930s.

Ron Reiber, Hodgdon’s long-time chief ballistician, told me the two best powders are 4064 and Varget, which is essentially the 4064 equivalent in Hodgdon’s “Extreme” series. As recounted in the two Ken Waters articles mentioned earlier, other powders have come and gone, some delivering performance near comparable to 4064. In 1978, he liked H-205 almost as well as 4064, but it’s long gone; in 2000, it was XMR-2495, now known as Accurate 2495. It’s still available, but Hodgdon provides no data for it for the Swift. Interestingly, not one load in Waters’s 2000 load chart reached 4,000 fps. For that matter, the only ones he reported in 1978 were with 45-grain bullets. In both sets of tests, he used a Ruger Model 77 with a 24-inch barrel, whereas my Model 70 barrel is 26 inches. That makes a big difference.

There are variations in maximum loads with 4064, depending on the year of the manual, the test rifle employed, and barrel length. Hodgdon’s current maximum recommendation is 38.4 grains, delivering 3,905 fps with a 50-grain bullet from its 24-inch test barrel.

Older manuals, using rifles with longer barrels and possibly roomier chambers, allow heavier charges. For example Sierra Reloading Manual No. 2 (1985) uses a Model 70 with a 26-inch barrel, allows up to 40.2 grains, and records 4,100 fps; in Sierra Reloading Manual No. 5 (2003) the test rifle is a Savage Model 112VSS, 26-inch barrel, and the maximum load is 39.9 grains for a velocity of 4,000 fps.

Speer Manual For Reloading Ammunition No. 7 (1966), using a Mauser custom rifle with a 25-inch barrel, gave a maximum load of 41 grains of 4064 with a 50-grain bullet, and velocity of 3,994 fps.

To say that current load data for the Swift is all over the map is understating the case. Not surprisingly, in a cartridge this old, with so many rifles of different descriptions chambered for it over the years, extreme caution is advised. This is not because of the cartridge itself, but because of variations in rifle quality. The factory rifles – the pre-’64 Model 70, Ruger 77, Savage 112V and Remington 700 – are beyond reproach, but custom rifles, especially older ones, should be approached with caution. Loads should be worked up very carefully, starting at close to minimum, and looking for adverse pressure signs every step of the way.

In recent years, some cartridges have claimed to have dethroned the Swift as velocity king, but they’ve done so by using bullets as light as 35 to 40 grains. Try those in a Swift and see what happens!

My Model 70 is now a cool 70 years old and looks archaic beside today’s rifles that claim extraordinary accuracy. It has an American classic-style walnut stock, blued steel, a bolt so smooth it’s almost liquid, and feeds cartridges effortlessly. It is the epitome of a varmint rifle from a revolutionary stage in American rifle history. Its barrel has the trademark boss halfway along, where the rear sight is mounted and a screw attaches it to the forend. This is a major drawback in an age of free-floated barrels. But, because I wanted to see how the rifle would do in factory form, I altered nothing.

Originally, I intended to try some of today’s heavy-for-caliber bullets – 70-90 grains – but with a 1:14 twist, that was hopeless. No one makes a 48-grain bullet, so I stuck with 50 grains, which is where the Swift really made its reputation.

The accompanying table tells an interesting story.

While IMR-4064 delivered all the velocity one might want, reaching the Speer Manual For Reloading Ammunition No. 7’s maximum, accuracy fell off as velocity increased.

Ron Reiber’s second recommended powder, Varget, at a maximum load (Hodgdon data) was shy on velocity but okay on accuracy.

Hodgdon’s Accurate 2700 was listed as delivering the highest velocity with a 50-grain bullet, and its published maximum certainly did that (see table), but with one blown primer, four enlarged primer pockets, and noticeable recoil. After that, I did not shoot a group.

The load with H-4895 came from Jim Carmichel’s book, was well short of published maximums, and not only delivered a lovely sub-1-inch, five-shot group, as promised, but did so with almost no recoil.

The conclusion here is that every rifle is an individual and needs to be approached as such. The fact that one published load resulted in frightening pressures (Accurate 2700) while other maximums seemed very mild – Hodgdon’s current maximum with IMR-4064 is 2.6 grains less than Speer’s 1966 recommendation – strongly indicates one should not make presumptions, and always err on the side of caution.

Working with an 88-year old cartridge in a 70-year old rifle, using one powder (IMR-4064) that is 85 years old and another (H-4895) almost as ancient, and getting the results I did, says a great deal about the rifles Winchester was making in the early 1950s. It also says a lot about the 220 Swift.

The fact that it’s still around, has survived all the misplaced and sometimes malevolent criticism, has eager buyers when a good rifle comes up for sale, has companies like Hornady and Nosler making brass, and Redding supplying their superb match die sets – well, obviously the 220 Swift is still widely appreciated.

One final thing: I don’t plan to part with this Model 70 220 Swift anytime soon. It’s just too interesting.