Long-Range Handguns

Varmint Loads for SIngle Shots

feature By: Layne Simpson | April, 21

In addition to shortening the barrel to 15 inches or so, he heated and reshaped the tang (or tangs) of an action and fitted a grip made of black walnut from a tree he had removed from his back yard many years before. His crowning achievement and the one he was most proud of, was a handgun in 30-06 on a 1903 Springfield barreled action. I never got around to shooting that one, and while I never actually owned one of his .22s, he often loaned me one to bump off a few cottontail rabbits and grey squirrels.

Moving forward a decade or so, Alfred Goerg was a handgun hunting pioneer who took all sorts of game with revolvers in 22 Kay-Chuk, 357 Magnum and 44 Magnum. He was one of the first to regularly use scopes on handguns. In addition to writing about his adventures, Goerg made and sold a number of useful products related to handgun hunting, including a well-designed shoulder holster and a tool for drilling hollow cavities into the softnose bullets of factory ammunition. I had the latter for 357 Magnum ammunition and it worked great. Goerg also used a custom single-shot handgun on a Remington rolling-block action in 257 Roberts and as I recall, he used it to take a variety of varmints as well as a good mountain goat. His book, Pioneering Handgun Hunting, published in 1965, is quite difficult to find today. During earlier years, his articles on handguns for hunting appeared in several monthly publications. Sad to say, at the age of 53, Al Goerg died when a bush plane in Alaska went down not long after his book was published. Among other good things, he revealed to the shooting world that handguns were quite suitable for more than plinking and personal defense.

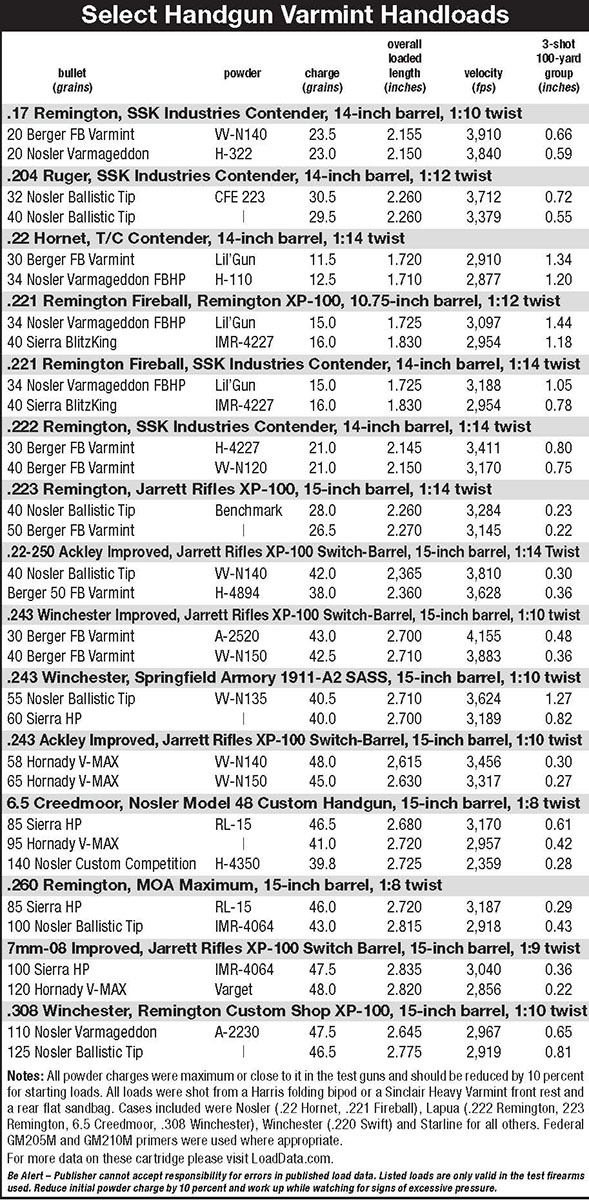

Probably influenced by the writings of Alfred Goerg, Remington introduced its bolt-action, XP-100 pistol in 1963. The action was a single-shot version of the Remington Model 600 rifle action. Experimental models of the new handgun had been chambered for the 222 Remington, but a huge fireball at the muzzle of the 10.75-inch barrel prompted shortening the case for less powder consumption and calling the new cartridge the 221 Fireball. My friend Les Bowman had been shooting prototypes of the pistol for several years and was first to receive a production model. His report on the new gun featuring a recently introduced Redfield 2-4x long eye relief scope, and the performance of its cartridge on coyotes appeared in 1964 Gun Digest.

Several other variations of the XP-100 were eventually produced, most with 15-inch barrels. The 221 Fireball and 223 Remington were the only pure varmint cartridges offered in standard-production guns, but others, including 17 Remington and 22-250, were available from Remington’s custom shop. The XP-100R was the last variation offered by Remington. Built on the Model Seven rifle action, its magazine held five rounds. Because of the magazine, the grip had to be shifted to the rear, making the gun awkward to handle and to shoot from any position. Mine is in 7mm-08 Remington, but the 223 and others were available.

The Thompson/Center Contender designed by Warren Center and introduced in 1965, became extremely popular because it utilized interchangeable barrels in various calibers. Two firing pins, along with a switch on its external hammer, allows barrels chambered for rimfire and centerfire cartridges to be used. Early chamberings were 22 Long Rifle, 22 WMR, 22 Remington Jet, 22 Hornet and 38 Special, but the options eventually grew to numerous cartridges ranging from the 223 Remington to 45-70 Government.

A big difference between the Contender and some of its competition is the amount of cartridge back-thrust its frame is designed to handle without complaint. The 223 Remington, as an example, is commonly loaded to a maximum average chamber pressure of 55,000 psi, but due to the relatively small surface area of its case head, back-thrust or force against the standing breech of the Contender is comparatively low. As cartridge case head surface area increases, chamber pressure must be lowered. Maximum pressure for the 30-30 Winchester, for which the Contender has long been chambered, is 42,000 psi.

Moving on to even greater cartridge head surface area, maximum allowable pressure for the 45-70 Government in the Contender is 28,000 psi. The later G2 version of the Contender is an improvement because opening it requires less pressure on the spur of the trigger guard. Equally important, if the hammer is cocked and then lowered, the gun does not have to be opened and closed in order to recock the hammer.

Through the years, I have hunted big game a great deal with long-range handguns, and prefer the Contender over the XP-100 because it is lighter and easier to carry. When bumping off varmints from a sandbag rest, the XP-100 has an edge because cycling its bolt requires less effort and gun movement than breaking down the barrel of the Contender. A custom XP-100 can be more accurate than a custom Contender, but the difference is seldom great enough to matter in a prairie dog town.

Another long-time favorite is the MOA Maximum, introduced years ago by my friend Richard Mertz. His company, MOA Corporation, was located in Eaton, Ohio. Like the Contender, barrels of various lengths interchange and were available in about any cartridge you could think of, including the 375 Holland & Holland Magnum. Mine has several barrels, with those in 22-250 and 260 Remington receiving the most use through the years. The MOA has a falling-block action along with an external hammer, and its accuracy equals that of the best custom handguns built on the XP-100 action. In the MOA Long Range Handgun Match hosted by Richard Mertz in Sundance, Wyoming, each year, targets are shot at various distances out to 1,000 yards. Handguns from all makers can be used, with the 260 Remington, 6.5-284 Norma and 6.5 Creedmoor, 6mm Dasher and 6mm Creedmoor among the more popular cartridges.

Other long-distance handguns are too numerous to cover in detail here, so I will just hit the high spots. Bolt actions included the Wichita MK-40 (which had a right-hand stock and a left-side-load action), the Savage Striker, Model 20 REB from Ultra Light Arms and the Model 84 Predator from Kimber of Oregon. The Predator I had was in 223 Remington, and in addition to being incredibly accurate, it had a gorgeous Claro walnut stock. The Voere VEC-91, chambered for caseless 22 and 6mm cartridges that were electrically ignited have also been tested.

Then came the SASS, available from Springfield Armory. When installed on the lower of a Model 1911 pistol, it became a single-shooter. Interchangeable barrels in various calibers were available, including 223 Remington (which I used on prairie dogs in several states) and 243 Winchester with which I bagged a very nice pronghorn buck in Wyoming. The latest in a long line of handguns designed for long-distance shooting is the Nosler Custom Handgun on a single-shot version of the Model 48 rifle action.

For all-around use in varmint fields, the 223 Remington is the best choice, same as it is for rifles. I have shot it alongside the 22-250 Improved, and while the bigger cartridge is a bit better on windy days and it does reach out a bit farther, the difference between it and the 223 is not enough to justify shorter barrel accuracy life and additional muzzle blast. I love the 17 Remington and 204 Ruger, but at the end of the day I don’t shoot them any better than the 223.

The 220 Swift and the 22-250 are seen at their very best when the targets are groundhogs in the East and rockchucks out West. Unfortunately, coyotes have just about wiped out groundhogs. Years ago, my wife I lived in an area of Kentucky where hoards of them were munching their way through thousands of acres of soybeans and farmers welcomed us with open arms. Not long back, I was on a week-long spring gobbler hunt in that area and did not spot a single groundhog, nor a fresh den. Sadness overcame me as I stood there and thought about the many wonderful days of varmint shooting that were long gone and would never again be enjoyed.

Bigger cartridges such as the 243 Winchester, 260 Remington, 6mm Creedmoor and 6.5 Creedmoor are not ideal for high-volume shooting in a prairie dog town, but they are not bad choices for larger targets ranging in size from rockchucks to coyotes. They pack a bit more punch at barrel straining distances, and are slightly better at staying the course on windy days.

When in calling foxes and coyotes, I prefer an old Bausch & Lomb 2x scope with long eye relief. The Burris 1-4x variable is also good because it has sufficient field of view for in-your-lap shots along with enough magnification for a bashful critter that hangs up at 100 yards and beyond. Unfortunately, Bausch & Lomb is long gone and Burris no longer has the 1-4x handgun scope in its lineup. For long-distance shooting of varmints, the Burris 3-12x is tops. Some of my guns wear the 2.5-8x Nikon, but four additional xs of the Burris scope really pay off when shooting the smaller varmints such as prairie dogs and flickertails.