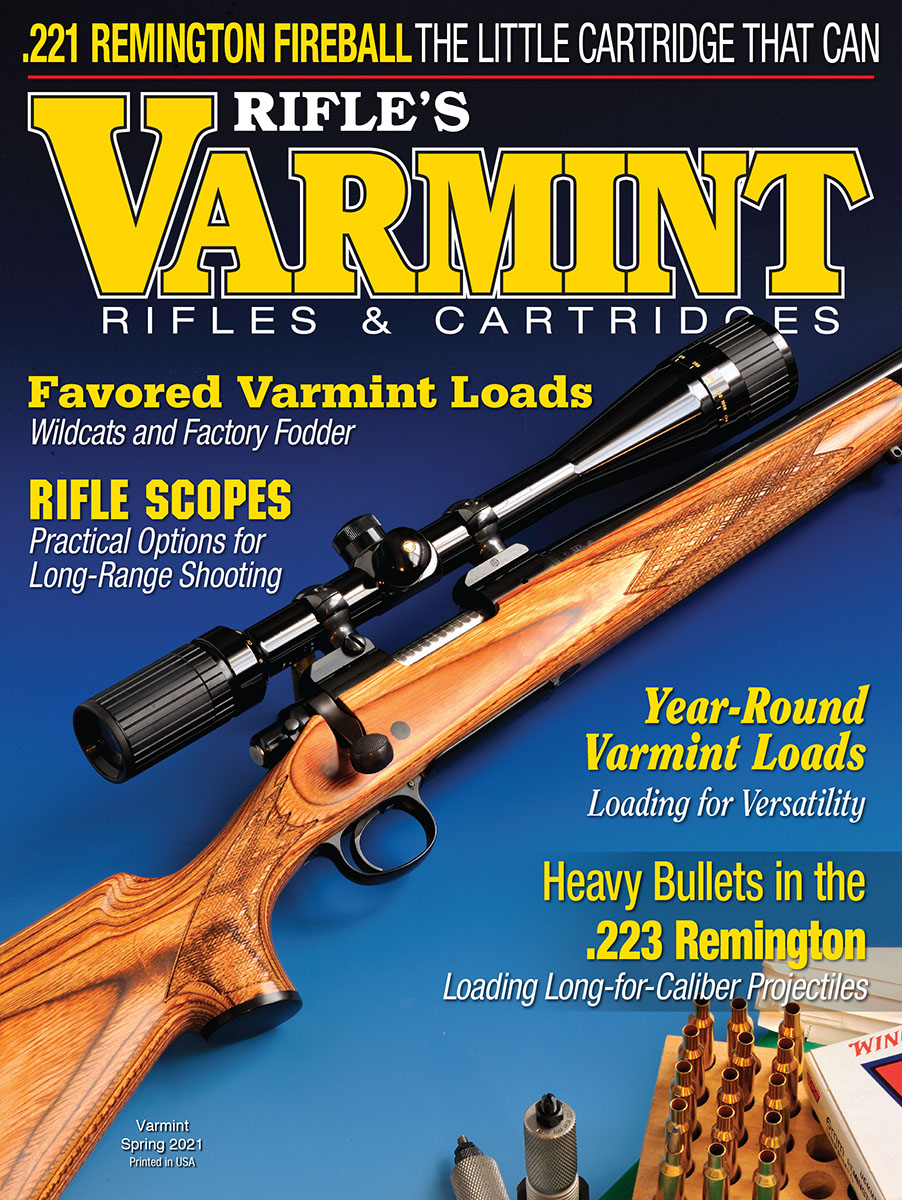

Varmint Rifle Scopes

Practical Options for Long-Range Shooting

feature By: Patrick Meitin | April, 21

My varmint shooting passions developed as a teen and only grew with the passing of more than 40 years. Initially, I wasn’t so much obsessed with varmint shooting in and of itself as I was looking for any excuse to shoot centerfire rifles. I was blessed to have grown up in the West, to have had quick access to wild places, and during a historical spike in raw fur prices. This allowed access to an enviable array of big-game opportunities, and also provided the funds necessary to purchase quality rifles and optics of my own.

Varmints – eastern New Mexico jackrabbits and prairie dogs mostly – were approached as practical warmup for the big-game hunting that ultimately drove me. Predators – called in or encountered coyotes, bobcats and grey foxes – were viewed as dollars and cents. I didn’t own a true varmint rifle (unless you count a 243 Winchester, also used to tag mule deer, pronghorn, elk and aoudad sheep) until released from the confines of formal education.

As my passions moved irrevocably toward bowhunting, I began trading my big-game rifles for true varmint guns. No longer finding the need for dual-purpose rifles, my optics slowly became as specialized as the rifles themselves; swapping light sporters ideal for trekking steep mountains for heavy-barreled, blocky-stocked creations made to shoot from atop portable benches or steady bipods while shooting tiny targets at extended yardages.

This specialization has ultimately led to scope choices some hunters deem excessive. This includes price, as most of my favorite varmint rifles feature optics double the price of the rifle itself. This runs counter to choices I generally observe in the field or firearms periodicals. All are variables, but my tastes run toward top-end magnification. I always say, “You can’t hit what you can’t see.”

I understand the nexus behind the usual knocks against excessive magnification: midday heat shimmer, every heartbeat telegraphed into wiggling reticles, the difficulty of picking up isolated targets, and even weight. I find the heat shimmer argument interesting, as my considerable in-field experiences doesn’t actually mirror what I regularly see in print. My long-range varmint rifles have optics with top-end magnifications from 27x to 60x. Yet, counter to common consensus, those scopes are rarely twisted off the highest magnification during a day of shooting, even when late-spring temperatures soar.

Rimfire Optics

I approach rimfire varminting as seriously as centerfire pursuits. I shoot a couple of different Ruger 10/22s tricked out with aftermarket parts, including match grade replacement barrels, ergonomic stocks, triggers, Little Crow Gunworks GRX recoil lugs and professional-grade glass bedding. I’m also fond of my Marlin XT-17 17 HMR. These are the rifles I choose for “walkabout shoots” while prowling clear-cuts or vast desert atop an ATV, or while moving between portable-bench setups. During an average day shooting eastern Oregon “rats” (tiny Belding’s ground squirrels), bulk packs of hollowpoint 22 LR ammunition are consumed per diem.

First and foremost, a rimfire scope should include an objective-bell or side focus (preferred) parallax adjustment. There are many scopes with rimfire labels but without a focus option. They are worthless to me. When shooting .22s in particular, targets are engaged at ranges from point-blank to maybe 150 yards, and I prefer tack-sharp targets.

Another 10/22 favorite was a 16.5-inch Adaptive Tactical Tac-Hammer barrel with Little Crow Gunworks Boom Tube. It also has an Archangel adjustable stock, Timney Trigger and GRX recoil lug. It has a Bushnell Rimfire 3-12x 40mm scope with exposed turrets and side parallax adjustment. Both include ballistic hash marks. Both serve as excellent examples of what a serious (and affordable) rimfire scope should be.

Rimfire scopes need not have a “rimfire” label. Last spring, I shot a Bushnell Engage 2.5-10x 44mm atop Ruger’s American Rimfire Long-Range Target. The Engage is designed for centerfire big-game hunters and includes a 30mm tube. It proved a welcome fit to the accurate .22 rifle. It includes Deploy MOA hash marks for holdover reference when making quick shots, or exposed turrets when more time is permitted. As importantly, side parallax focus is included.

My Marlin XT-17, with its heavy 22-inch barrel set in a stable laminated stock and featuring a crisp adjustable trigger, once held a high-end turret scope. On calm days, shooting tiny ground squirrels to 350 yards became as fun as banging steel with a .338 Lapua at 1,000 yards. Today my “Hummer” has a scope likely more fitting to its capabilities; a Styrka S5 3.5-14x 44mm with large side-parallax wheel and handy drop reticles. This optic has proven an ideal fit for that cartridge’s capabilities.

Everyday Varmint Shooting

Here’s where my optics choices seem to deviate a bit from mainstream, driven again by my belief that you can’t hit what you can’t see, and referencing targets such as tiny ground squirrels or distant prairie dogs. (Optics suitable for called coyotes differ little from big-game hunting.) My prerequisites are fairly dogmatic: exposed turrets (Ballistic hash marks are welcomed as long as they don’t become cluttery.), side parallax adjustment, second focal plane, 50mm or larger objective lens and top-notch optics coatings. If forced to choose a single configuration, 6-24x 50mm is nearly ideal. I happily use ballistics hash marks, though I abhor busy “Christmas tree” reticles.

Sometimes ranges are such that dialing turrets simply isn’t necessary. Despite common braggadocio, I’d wager the vast majority of small varmints are shot between 150 and 250 yards, be that over a ground squirrel colony or prairie dog town. At those ranges, it’s easy to establish gaps with provided hash marks, working out minute holds through trial and error based on a particular cartridge and load. What sets high-volume varmint shooting apart from, say, chance-encountered coyotes, long-range rockchucks – or especially big game – is a missed shot doesn’t represent a Greek tragedy. While shooting small varmints, it’s not uncommon to take multiple shots at a single target, or the opportunity to shoot companions occupying the same mound after your original target goes to the ground. In other words, it’s pretty easy to make quick hold adjustments between shots in trial-and-error fashion.

I’ve heard it said that 300-plus yards is the distance where hit-to-miss ratios begin to deteriorate exponentially. I agree, especially when using “Kentucky Windage” to get the job done. Yet, I’d contend that when ranges pass 300 yards – again on small varmints – kids hold over target and adults twist turrets. Modern ballistics charts, finely tailored handloads and some confirmation at the range make cold-shot hits at extended ranges completely feasible on rockchuck to coyote-sized critters that feature more margin for error.

I’ve never really understood the first (FFP) verses second focal plane (SFP) debate in direct regard to varmint shooting (or big-game hunting for that matter). FFP keeps reticles consistent in relation to the target through the entire magnification range, allowing more accurate through-the-scope yardage and moving-target lead estimations using MOA or MIL marks of known value. This, apparently, is useful to military snipers engaging targets in fluid battlefield scenarios. The problem with FFP reticles is they also appear thicker in relation to the target as magnification increases. We’re not military snipers, but varmint shooters engaging much, much smaller targets and with no need to judge range via reticle relationships. All of us own and have time to use laser rangefinders to establish range. SFP reticles remain fine as frog’s hair at every magnification, obscuring less target at longer ranges. The ability to aim at a specific point on even a tiny ground squirrel, provides confidence – contrary to shooting at an ill-defined blob.

Extreme Range

A few of my varmint rifles are decidedly specialized and are shot only when ranges stretch to extremes (400-plus yards), or while shooting beyond 300 to 400 yards when prairie wind stirs. My new Little Crow Gunworks 22 Creedmoor qualifies here, shooting 80- to 90-grain bullets with BCs in the .500s at 3,000 to 3,200 fps. My .24 bores include a custom 6mm Remington with 1:9 twist to handle bullets up to 107 grains at 3,000, and a Ruger Precision Rifle chambered in 6mm Creedmoor with a 1:7.6 twist to easily handle bullets weighing 110/115 grains and with BCs in the .600s at essentially the same speeds. These combinations cut 10-mph, 400-yard wind drift margins introduced by typical 22-250 Remington 50-grain ballistics, to margins measured in single-digit inches.

These, of course, simply represent my personal scope preferences. That’s the great thing about varmint shooting. It’s all about fun. These inclinations reveal my penchant for pushing things to extremes (which I do not advocate for big game), while other shooters are perfectly content shooting inside 250 yards with the same optics used on their favorite deer rifle.