New Loads for the 6mm-225

Testing a Classic Wildcat

feature By: Jim Mathhews | April, 21

The 6mm-225 Winchester wildcat is one of those rounds. Why, exactly?

Well, if someone seriously asks you that question, it could be argued they are not even remotely serious about their guns, reloading or varmint hunting. They probably also don’t have any imagination, like to laugh or have a copy of Cartridges of the World. Sometimes we have wildcats just because.

I suppose a more simpleminded answer would be to get 22-250 ballistics with equal bullet weights, but using a little less powder and a slightly larger diameter bullet. But that’s not really the point.

We could say it’s made on rimmed cartridge case. In fact, the 6mm-225 is made from the last legitimate varmint round introduced by a company just for varmint hunting with a rimmed case, which is ideal for single-shot rifles. So it has nostalgia and is a relic of a bygone era. But that’s not really the point.

The point is that it’s just cool, and different, and it has very respectable ballistics.

The .225 cartridge was loosely based on the mildly popular 219 Zipper, but with a reduced rim diameter so it would run through the same bolt faces as the .30-06 (and cases with a similar head size) at .473 inch. This made the round suitable for both bolt guns and classic single shots. Who knows if Winchester was already considering a reintroduction of its Low Wall or High Wall single shots? Perhaps the company staff had been tipped off that Bill Ruger would bring out his No. 1 single shot just a couple of years later in 1967. Sadly, the 225 was never chambered in the No. 1 or the High or Low Walls, so those scenarios seem unlikely. Was it just more nostalgia than common sense that led to the rimmed case?

The 225 was originally chambered in post-64 Winchester Model 70s and the even cheaper Model 670s, both with the then-new push-feed actions, along with the even less expensive Savage Model 340. This means the rifles in this caliber were not even coveted on the used gun market once they were discontinued. Never mind that at least two well-known gun writers of that era (who are still active today) said the heavy-barreled Model 70s in 225 were the most accurate, out-of-the-box rifles they had ever shot at that time – and remained the most accurate factory guns until just recently.

If it wasn’t for wildcatters and single-shot rifles, Winchester might not even have continued making ammunition or brass for the round. Until this current ammunition crisis, the company has continued to make runs of the cartridge for 225 fans out there and those who are shooting wildcats on this case. The ammunition is still listed on the Winchester ammunition website. (Finding brass or ammunition in today’s market is difficult, however.)

Perhaps the most famous line of wildcats on the 225 case were those designed by J.D. Jones for the T/C Contender handgun, mostly intended for handgun silhouette competition that was extremely popular in the 1970s and 80s. The case was opened up to 6mm, 257, 6.5mm, and 7mm, the neck shortened and the case blown out with a sharper shoulder to increase case capacity. These rounds were all able to use heavier bullets that easily toppled the heavy ram targets at 200 yards. These rounds all had followers for both silhouette shooting and hunting.

These are the kinds of things old shooting and hunting buddies talk about when sitting around a table or at gun clubs. So when my old friend Charlie Merritt told me he had a Contender rifle in 6mm-225 one day at lunch, one thing led to another and I had the gun on loan a week later. Merritt’s wears a Bushnell 3200 4-12x scope, a synthetic stock, and the barrel was made by MGM. The complete gun weighs just a snick over 6 pounds, which is a perfect weight for a walking gun. It is also very fast handling, making it ideal for coyotes bounding into a distress call.

“Walking varminter” is a term you don’t hear or see much these days. Today, the rage is uber long-range shooting at small targets. Guns used for this activity are usually heavy-barreled gems that shoot itty-bitty groups with high ballistic coefficient bullets. They are heavy guns with big optics, and lugging them a mile to a ridge that overlooks a valley filled with ground squirrels or prairie dogs isn’t done much, especially when you can find a spot closer to a dirt two-track somewhere.

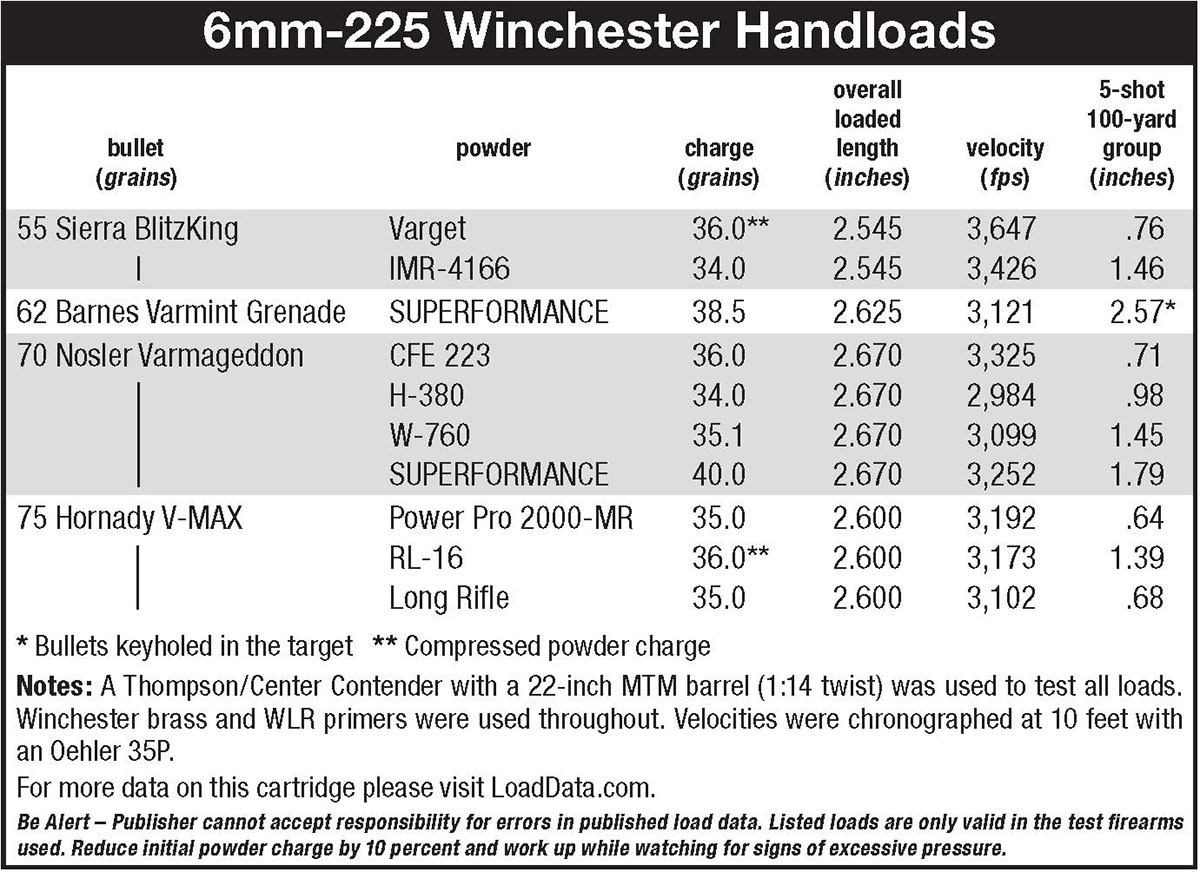

Finding loading data for old wildcat rounds like this is not impossible, but it is practically impossible to get data for contemporary powders. So I started with very conservative loads with some of the new powders and worked up, measuring case-head expansion and paying close attention to how the action opened after each shot. I used a bunch of ladder loads to work up to midrange loads that approached or reached top velocities possible at safe pressures. None of the loads in the table were maximum in the Contender, but a few are approaching maximums. That means other 6mm-225 shooters should use the usual precautions about working up to the loads listed in the accompanying table.

The table shows that accuracy was good across the board for such a light gun, with the exception of the 62-grain non-lead Barnes. This bullet has shot very well in a number of 6mm cartridges tested, and it was included for varmint shooters who prefer or are mandated to shoot non-lead bullets. Sadly, the bullets keyholed through the target at 100 yards because of the length of the non-lead slug. The last test I shot with the bullet – the load in the table – had very slight keyholes, and I thought that it might stabilize at higher velocity, but that is a test for another day. The load was kept in the table for shooters who might have or build up a 6mm-225 with a faster twist barrel.

Most of the powders had very low extreme spreads for this velocity range. The Varget load with the 55-grain Sierra had only a 26-fps extreme spread for its average 3,647 fps velocity, and it shot a nice .76 inch, five-shot group. The ancient H-380 turned in the lowest five-shot extreme spread of just 25 fps for the 2,984 fps velocity this very light 34.0 grain load turned up with the 70-grain bullet. CFE 223, Power Pro 2000-MR, and RL 16 all had extreme spreads less than 40 fps, and none of the loads had extreme spreads more than 50 fps.

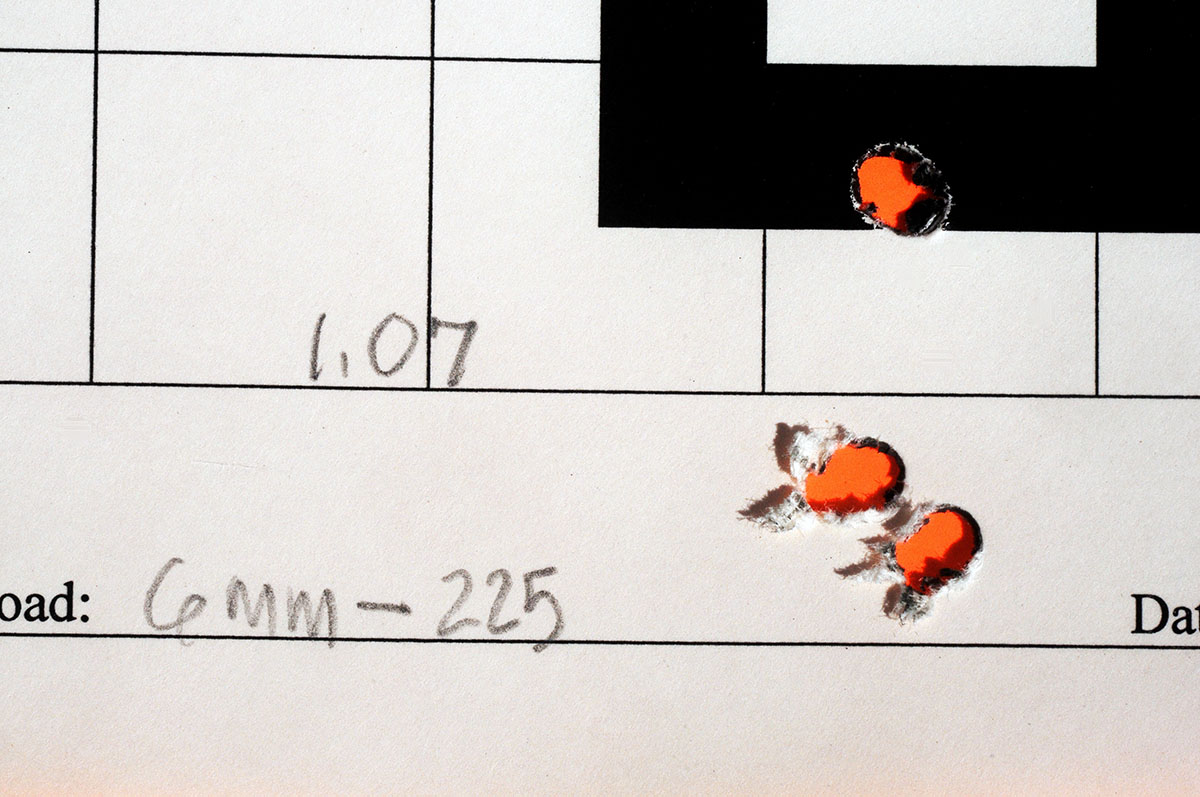

This shot-to-shot consistency was reflected in the accuracy, with half of the groups shooting under an inch, and at least one of those with each bullet weight. I confess to not being a very patient range shooter, and a couple of the larger groups were definitely more a reflection of impatience and shooting strings too quickly. When the light MGM barrel was not given time between groups to cool down, this led to the sight-picture wiggling in heat waves and bullets spiraling away from the group center. The first three shots were often clustered in one hole and then the next two shots slipped out of the group as the barrel got hot.

By way of comparison, the 6mm-225 is pushing the 55-grain bullet at about the same velocity at the 22-250 with a bullet of the same weight, both around 3,650 to 3,700 fps, depending on the load. The same is true for the 75-grain bullet in both calibers, with both going around 3,200 fps. There is also very little difference between the two calibers bullets’ ballistic coefficients at equal weights and mean trajectories are similar.

After shooting this little gun at the range and carrying the 6mm-225 on a coyote calling excursion, I might have to try and talk Charlie Merritt out of this rifle. I also certainly wouldn’t hesitate to pick up a gun in this caliber, or the parent 225, if I saw one at a gun show or on a dealer’s shelf. Why? Well, just because.