Silent Varminting

Pros and Cons of a Suppressor

feature By: Art Merrill | October, 22

Perhaps invariably, the first thought that comes to mind regarding suppressors is not varminting, but their usefulness for silent assassination – thank you

Regardless, the National Firearms Act of 1934 placed a $200 “transfer tax” on suppressors, ensuring few could afford them. That doesn’t sound like much money, but $200 in 1934 is the equivalent of $4,315 today, and we’re not suffering a depression. It was, effectively, regulation-by-tax. Through the years, apparently most shooters considered suppressors expensive and useless curiosities, as it was illegal to hunt with them. Like others, I certainly had no interest in them until individual state game agencies started permitting their use for hunting.

Suppressors have very practical functions as hearing protection and to avoid worrying anyone nearby with our gunshots. When we are shooting or hunting on public lands, for example, suppressors are a courtesy to nearby residences and to hikers, anglers, birdwatchers and anyone else within earshot who might be enjoying the outdoors. For the pest-removal aspect of varminting, suppressors can offer the opportunity for rapid shots at multiple targets, such as among drays of ground squirrels in a horse pasture, because there is no gunshot to send alarmed bystanders scurrying for their holes. With subsonic ammunition, the “crack” of the bullet is eliminated, as well. With this combination, a varminter working a ranch at calving time can dispatch several coyotes in a pack before the confused remainder decide something is very wrong and it’s time to go.

Subsonic ammunition in a suppressed firearm works very quietly, indeed. A friend recently hunted whitetails on a Texas ranch with a suppressed rifle and subsonic .300 Blackout ammunition. Sometime during travel, his scope was unknowingly knocked out of zero, and he ultimately fired four shots over a buck’s back while the deer stood unconcerned before finally meandering off unfazed.

The most popular suppressors today are the type that screw onto a threaded-barrel muzzle. Second is the integral suppressor, one that is in some way a permanent part of the barrel or firearm. There’s a downside to everything, and the obvious one for integral suppressors is that they are typically a one-gun tool. Detachable suppressors have the advantage of just that – being detachable. This permits the shooter to purchase a single suppressor and attach it to any firearm with a threaded muzzle shooting similar-diameter bullets and of comparable or lesser power, such as a 223 Remington-rated suppressor on a 22 Long Rifle firearm. Their downsides may or may not be important to the individual shooter. Detachable suppressors typically change a bullet’s point of impact (POI), requiring sighting-in adjustments each time a suppressor is attached or removed. Also, being detachable and comparatively small (especially in 22 LR size), they are more susceptible to loss, which would make the Federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms very unhappy.

Among all the words penned about the Model 77/22, the most oft-repeated is that it is a big-game rifle scaled down for the 22 LR, which is literally true as Ruger based the Model 77/22 on the successful Model 77 centerfire rifle action that first hit the game fields in 1968. The Model 77/22 utilizes the same rotary magazine and V-block barrel mounting as its 10/22 cousin.

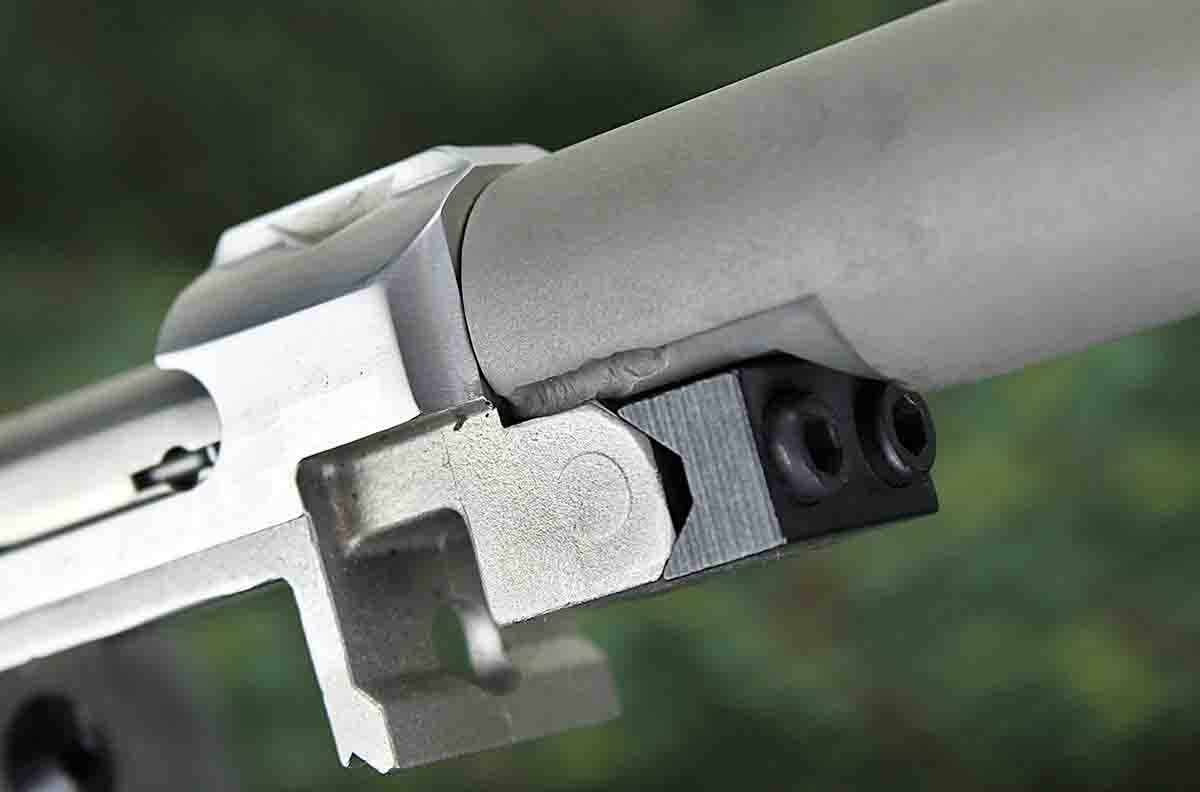

This Model 77/22 started life as the All-Weather variant in 22 LR, with a brushed stainless-steel receiver and barrel and with a synthetic Zytel “skeleton” or “boat paddle” stock. Though the metal still looks new, the synthetic stock has been relieved to accept the integral suppressor and bears witness to many days hunting in unforgiving Arizona sunshine. Originally weighing 6 pounds with a 20-inch barrel, the integral suppressor conversion has changed the barrel length to 12½ inches. The actual working portion of the suppressor is about 4½ inches long; its shroud, however, runs all the way back to the rifle’s receiver, the barrel still attaching with the factory V-block in the manner of Ruger’s 10/22.

My previous note about thread-on suppressors’ advantage notwithstanding, Ruger’s V-block barrel attachment makes this particular integral suppressor somewhat quick-detach, as well. In practice, a shooter could have a second, non-suppressed Ruger 77/22 barrel for varminting where state laws prohibit using suppressors.

It is no exaggeration to say the AWC integral suppressor reduces the 77/22’s gunshot signature to zero with subsonic ammunition. Pressing the trigger results in hearing only the “click” of the firing pin strike and the bullet slapping the paper. To illustrate, while running through a magazine and checking each individual shot with a spotting scope, I was momentarily confused to hear no “slap” and see no corresponding bullet hole in the paper after a shot. When I opened the bolt to check the chamber, it was empty: I had exhausted the magazine and the firing pin falling on an empty chamber sounded no different than when firing a live round. Now, that qualifies a suppressor as a true “silencer.”

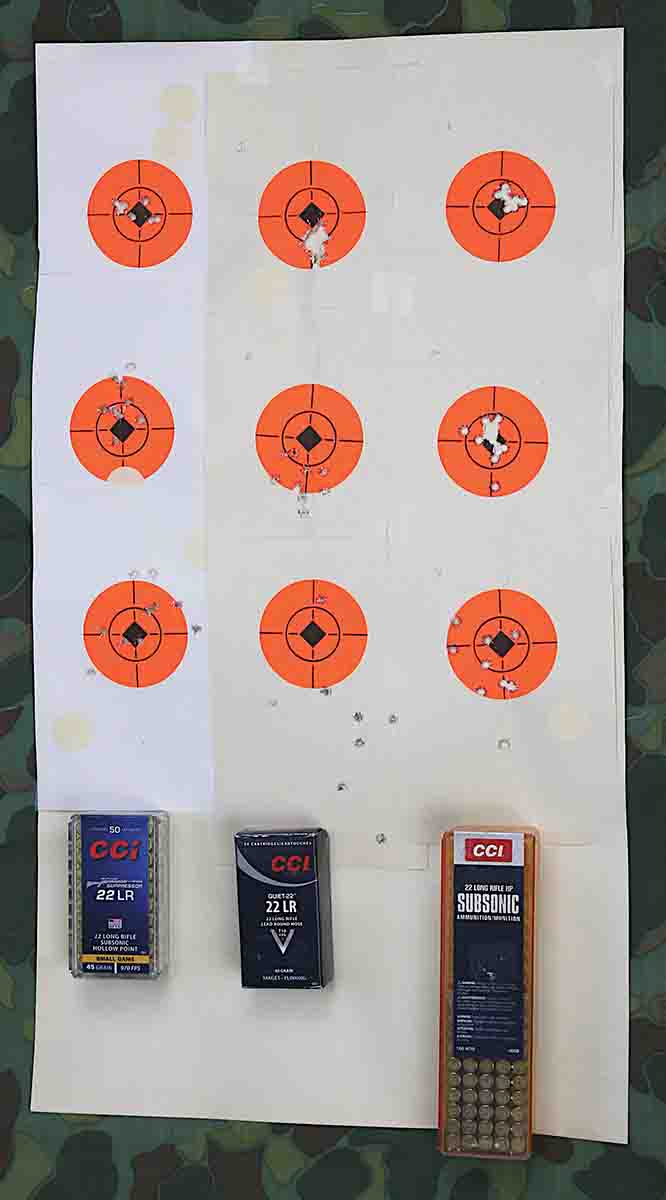

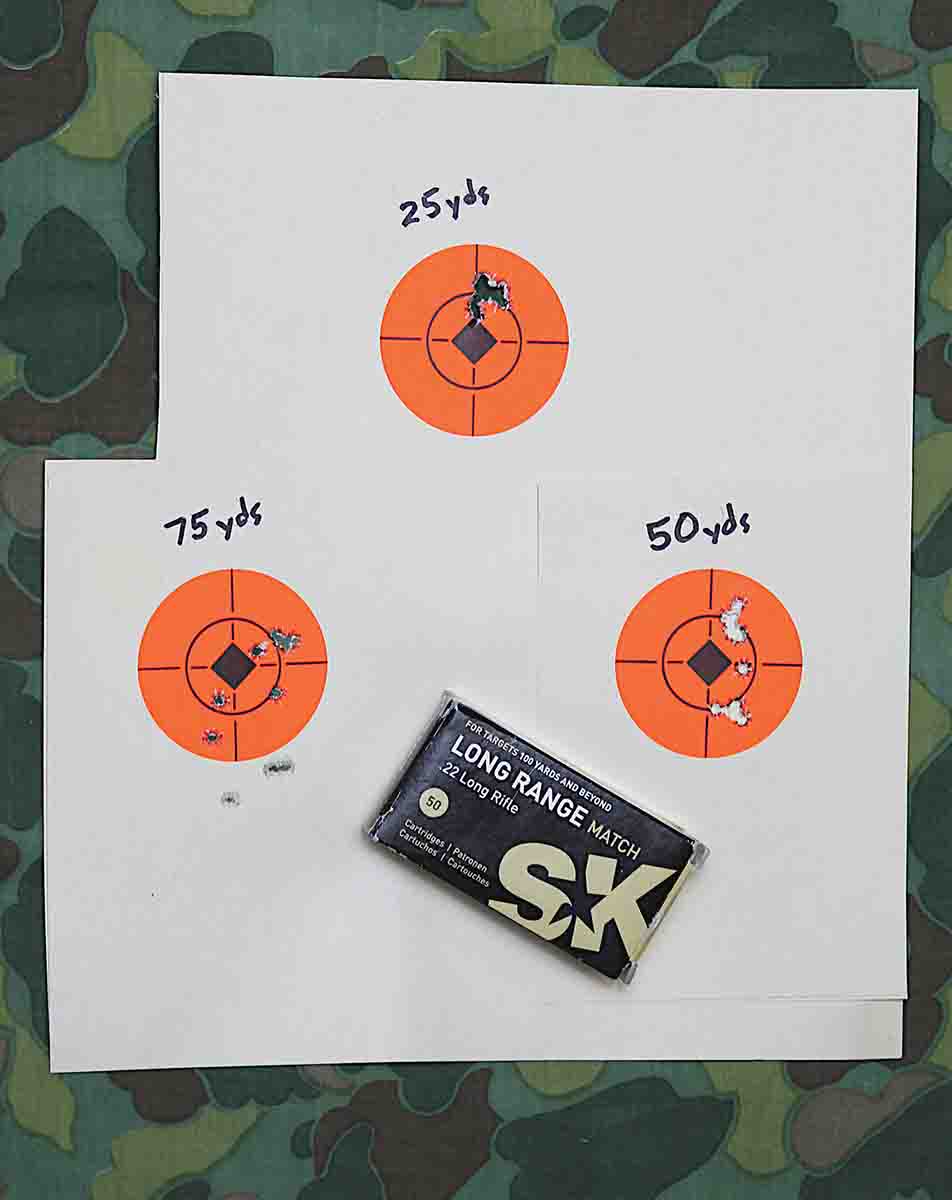

Subsonic 22 LR ammunition available for evaluating the suppressed rifle was necessarily confined by availability to three types of CCI brand plus SK Long Range Match, as shown in the accompanying table. Groups at 25, 50 and 75 yards were what a shooter might expect from any un-accurized, short-barreled rifle.

The speed of sound at sea level and 75 degrees Fahrenheit is about 1,133 feet per second (fps). At 3,150 feet elevation, where testing occurred, it is about 1,104 fps, so bullets started below that velocity are theoretically subsonic. While suppressors suppress the sound of a gunshot, they can do nothing about the loud “crack” of a supersonic bullet. As an experiment, I fired Winchester Super-X Hyper Velocity HP hunting/varmint ammunition at an advertised 1,435 fps in the rifle to get a subjective sense of the noise level. The ammunition grouped 10 shots into a single hole at 25 yards, but the “crack” of the supersonic bullet was loud enough to render the suppressor moot, as far as totally silent hunting is concerned, and enough to justify wearing hearing protection at an indoor range.

.jpg)

CCI’s Subsonic HP would have turned in an impressive 1.4-inch group at 75 yards, but a single, low, uncalled flyer opened up the group a full inch to 2.40 inches. Demonstrating again that advertising is routinely disproved by reality, the “crack” of the bullets indicated they were starting supersonic at 3,150 feet altitude.

CCI’s Suppressor Hollow Point is the go-to ammunition among those tested for this rifle, especially if one believes hollowpoint bullets are the only way to go to ensure humane kills. The ammunition produced the smallest group only at 75 yards, but the shorter-range groups are still minute-of-varmint, and the bullets were truly subsonic, taking full advantage of the suppressor.

As I would expect, drop from the slow-moving bullets is considerable. For example, from a 25-yard zero, the 710 fps Quiet-22 dropped more than 10 inches at 50 yards. At 75 yards, I’d cranked on 27 minutes of elevation from the 25-yard zero when the elevation knob reached its stop, and bullet impact was still about 4 inches low. As a curious aside, with all three CCI subsonic rounds and the SK Long Range Match ammunition, the shooter can clearly see the slow bullets arc toward the targets set at 50 and 75 yards.

Shooters all know that every individual 22 LR rifle will shoot best with a particular ammunition, and we must try a variety of ammunition to see which one the rifle “likes” most if precision is the goal. Taking full advantage of a suppressor narrows the choices dramatically, as there is a limited number of subsonic ammunition offerings. If we demand hollowpoint subsonic ammunition, we limit choices even further. We must also take into account the elevation where we will be hunting, as demonstrated here by supposedly subsonic ammunition clearly starting at supersonic velocity well above sea level. Also, of course, the severe bullet drop means ranges are necessarily short.

Is varminting with a silent 22 LR worth working within those limitations? Not for everyone, and not for every varminting application. But if the primary goals are multiple shots or not disturbing others, the answer is, “It’s worth a try.”

Thanks to Ken Seering at Double K Shooting Sports (doublekguns.com) in Humboldt, Arizona, for his assistance with this article.