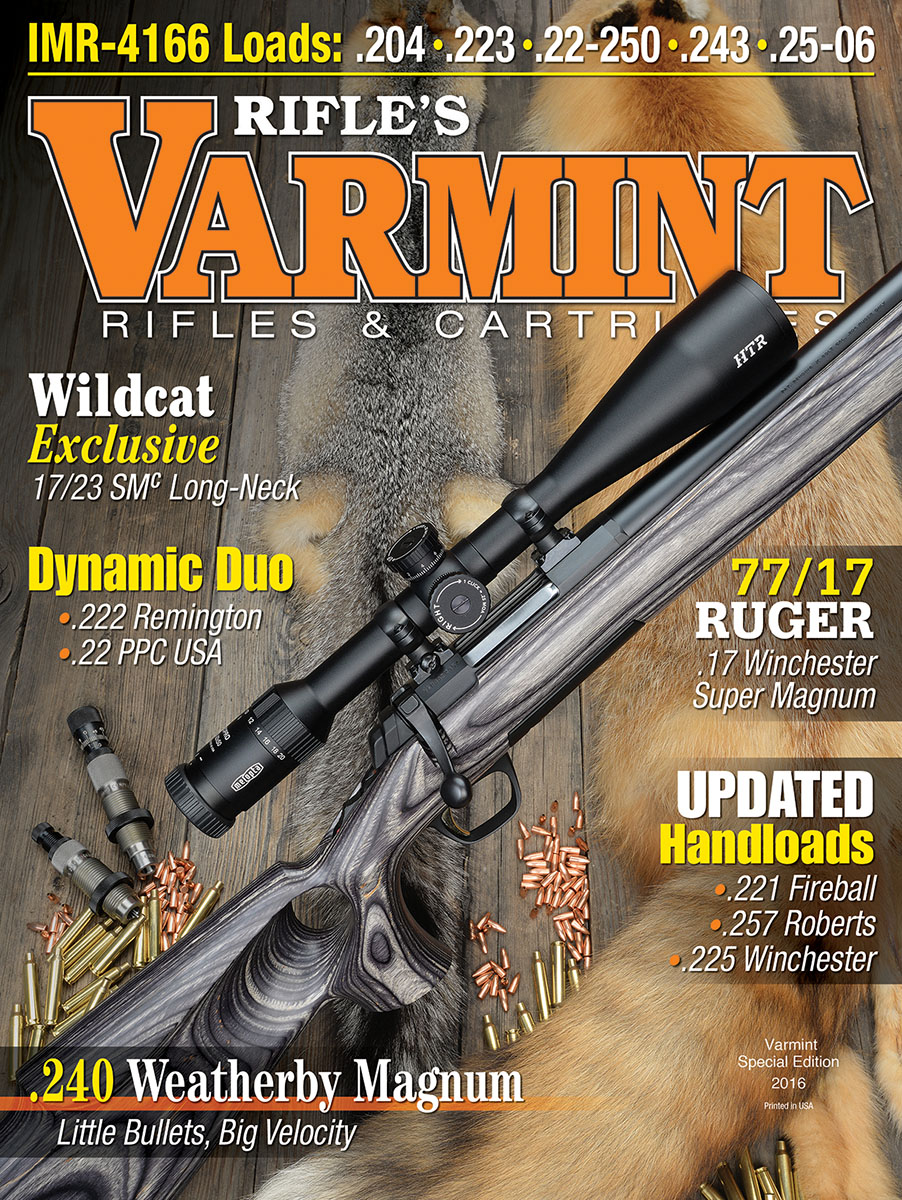

17 Winchester Super Magnum

Shooting the Ruger 77/17 Bolt-Action Rimfire

feature By: Lee J. Hoots | April, 16

Introduced in 2013, the 17 WSM’s timing was perfect given that 22 Long Rifle and 22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR) ammunition was (is) difficult to find. The 17 WSM’s greatest obstacle, however, proved to be a lack of firearms. Unlike the 17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (HMR), introduced in 2002 and easily housed in any rifle that could handle the nearly 60-year-old 22 WMR, the 17 WSM is an altogether different critter. It is larger in diameter and rim thickness, and its industry standard average pressure (33,000 psi) is significantly higher – 7,000 psi greater than the 17 HMR (26,000 psi) and 9,000 psi greater than the 22 WMR’s 24,000 psi. The case itself is a byproduct of Winchester Ammunition’s industrial tools (impact fasteners) division. With a thicker case wall, a heavy blow to the rim is then required to ignite the priming mixture. No bolt-action rimfire rifle at the time could easily be converted to handle the new cartridge, or so it seemed.

One of two rifles available at the cartridge’s introduction was Winchester Repeating Arms’ Model 1885 Low Wall, a modern version of the classic single shot but with a then-list price of $1,470! The main attraction of rimfire cartridges is the volume of shooting that can be done relatively inexpensively, so the steep price of the Model 1885 was presumably difficult to justify for many rimfire shooters, especially those preferring magazine-fed rifles.

The Savage B-Mag, a bolt action engineered for the new 17 WSM cartridge from the start, was also introduced. The first featured a slim barrel contour and met with mixed reviews, partly due to its peculiar, polymer trigger pull adjustment “nut.” For that or some other unknown reason, several Internet “reporters” had difficulty getting the rifle to shoot well. Due to the skepticism and cursory reviews, I ignored the rifle until a heavy barreled stainless variant appeared a year later, and that test sample performed well after a bit of fussing with the trigger adjustment. The 20- and 25-grain Winchester Ammunition loads available at the time more or less grouped five shots in 1.25 inches at 100 yards on average – if the barrel was kept moderately clean. Unfortunately, the B-Mag soon suffered a setback in the way of a recall specific to its safety mechanism, but it has since been reengineered. On its website, Savage currently lists six variations with 22-inch barrels of sporter and heavier, varmint-type contours, including stainless steel and laminated stock options.

Now entered into the fray is Ruger’s 77/17 17 WSM bolt action, introduced last year with relatively little fanfare. It is the most recent rifle to feature the company’s rotary magazine. Bill Ruger and Alexander Sturm founded Sturm, Ruger & Company in 1949 and introduced .22-caliber Standard and Target Model pistols within the year. The company has been an innovator in the rimfire business ever since. While it is difficult to pin down exactly when Ruger began exploring rifle magazine options, it is noted in Ruger & His Guns by R.L. Wilson that Bill Ruger turned a Savage 99 – known for its smooth-feeding, rotary magazine – into a blowback repeating rifle as early as 1938. As Wilson explains, Savage refused Ruger’s offer to buy the rights to the modification, and by 1964, with the introduction of the Ruger 10/22 rifle, Ruger had no doubt perfected his own version of the rotary magazine.

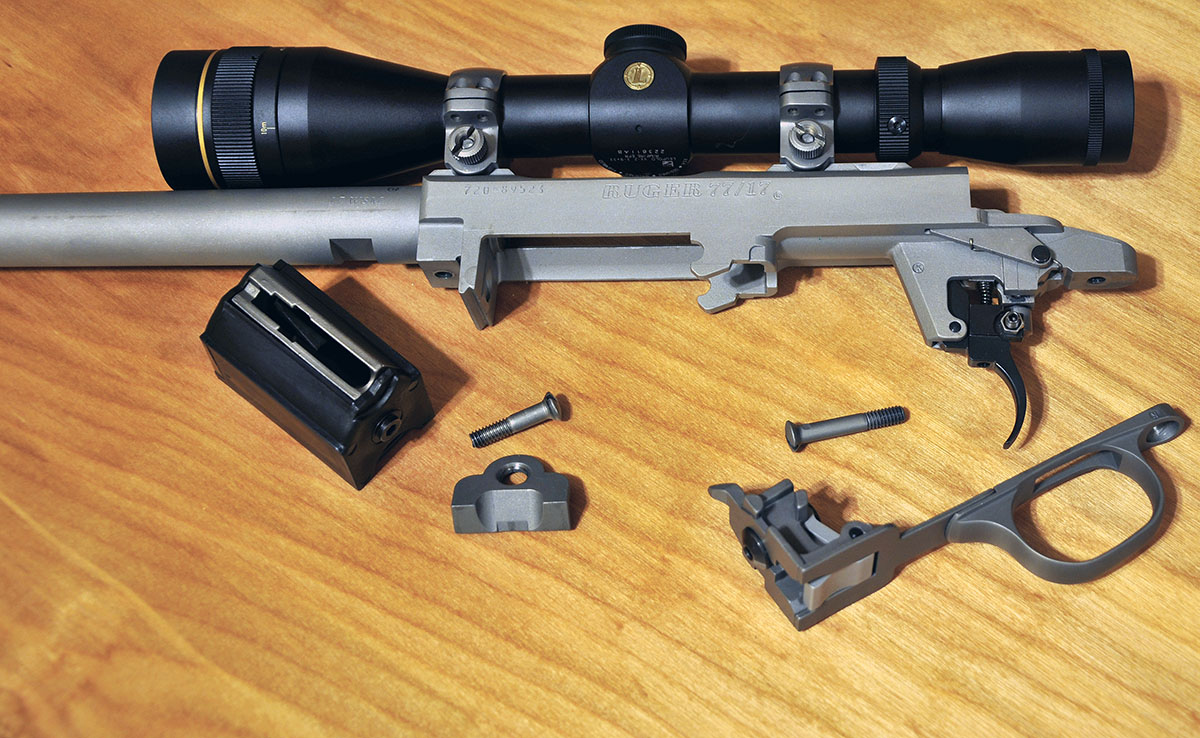

Not to ignore the roughly 10-year run of the Model 96 lever action, the same basic magazine was eventually used in several bolt actions, including the Models 77/22 (1984), 77/22 (Hornet, 1994), 77/17 (HMR, 2002), 77/44 (2009) and 77/357 (2012). These rifles have all been available in various configurations, and at least one option in each remains available today. For manufacturing, the beauty of this receiver’s design is that the bottom metal is somewhat modular. The trigger guard with a plunger-type magazine latch is a single piece that interlocks with twin recesses in the receiver. The separate front half acts as a wedge against a modest recoil lug, pushing it firmly forward to the stock inletting. The magazine simply slides into the stock inletting between the two halves.

During manufacturing, the receiver and bottom metal halves can be fine-tuned in length to accommodate magazines of various dimensions for various cartridges – within limitations, of course. The same basic receiver can likewise be relieved to best feed and eject those cartridges. Providing comparative dimensional differences would be appropriate here, but the only two examples on hand include a 17 Hornet purchased a couple of years ago and the 17 WSM test rifle, both of which roughly use the same magazine and ejection port dimensions. Their only significant difference is found on the bolts’ faces; the Hornet features a centrally located (centerfire) firing pin while the WSM features a firing pin located to strike the top of the cartridge’s rim, and strike it hard it must. While shooting the Ruger, only two cartridges failed to fire; while shooting the heavy-barreled B-Mag more than a year ago, several cartridges failed to fire.

Research has not revealed any recent changes to the receiver’s design, but minor modifications to strengthen the firing pin and/or spring, given the heavier rim on the 17 WSM cartridge, are suspected but are otherwise irrelevant. The bolt features twin opposing lugs that lock vertically and firmly into the receiver just behind the ejection port. The nonrotating front half of the bolt well shrouds the breech and magazine and features a single extractor. None of the newer Hornady branded loads failed to go off.

Like all Ruger bolt rifles built after the original “round body” M77, which was drilled and tapped for scope mounts and featured a sliding safety on the receiver tang, the Model 77/17 features a three-position safety and scope ring mounts integral to its cast receiver. Each rifle is supplied with medium rings to accommodate most scopes with a main tube of one-inch in diameter. (Rings for 30mm scopes can be ordered separately.) Depending on which scope is used, “low” rings usually work best for appropriately sized rimfire scopes and negate the likelihood of a loose cheek weld resulting from more drop of comb than necessary on most Ruger rifles’ buttstocks.

A Leupold VX-2 3-9x 33mm Rimfire EFR scope with an adjustable objective and a fine Duplex crosshair was mounted atop the 77/17. Bright and sharp, it served its purpose well throughout testing, though after shooting more than 200 rounds through the rifle, it occurred to me that a rimfire scope of the same or similar magnification without an adjustable objective would have worked equally well. Along with ordinary plinking, this particular rifle/cartridge combination is likely to be carried for cottontails in close cover or shot at jackrabbits out to 100 yards or farther. Fooling with scope adjustments, for just the right sight picture, could result in a missed opportunity during such hare hunting. That’s no scratch on the scope, but a fixed objective would handle both situations in addition to long mornings over a prairie dog town, where shots may be stretched out to 200 yards or so before centerfire rifles are unlimbered.

Early accuracy testing, albeit informal, proved lackluster as groups strung out both horizontally and vertically. The trigger pull, measured later with a Lyman digital scale, averaged well over five pounds. Normally I try to cope with factory pull weights when testing a rifle, because that’s how the general public will receive it, but this trigger proved too inconsistent and heavy. A search for an alternative ended with the purchase of a Rifle Basix R-UR drop-in trigger, partly as a result of looking for a reasonably priced option, and partly because I had never used a Rifle Basix trigger before. There are other choices available, including a Timney sear and spring that is said to work quite well, and most can be found on Brownells’ website.

Changing out the factory trigger for the Rifle Basix took only minutes, but a small amount of the stock inletting needed to be relieved with a Dremel Tool and a bit of sanding to provide space for the protruding “safety screw” so it wasn’t rubbing against the stock. With the new trigger set to 2.8 pounds, accuracy improved a fair amount, reducing five-shot groups by roughly half. Some tweaking of guard screw tension helped a little more.

Three different loads containing Hornady V-MAX bullets were tried, including 20- and 25-grain loads from lots left over from testing the Savage B-Mag, and a newer 20-grain offering shipped by Hornady. Risking redundancy, it should be remembered that all loads currently manufactured are done so by Winchester. This is important only in that different lots of ammunition with different brands should not necessarily be expected to perform identically, but they should be close enough for ground squirrels at 40 strides so long as bullet weight is the same.

All loads were checked for velocity using a PACT chronograph set 10 feet from the Ruger’s muzzle. The 25-grain Winchester loads gave an average velocity of 2,655 fps; the 20-grain Winchester load averaged 2,960 fps; and the Hornady branded 20-grain ammunition averaged 3,075 fps. For comparison, when checking velocities from the muzzle with the 22-inch barreled B-Mag more than a year ago, the Winchester 20-grain load averaged 2,987 fps, and velocity was 2,584 fps with the 25-grain load. Those velocities were recorded at 6 feet. Any variance in results from the two rifles should be taken with a grain of salt for several reasons, including that when chronographing with the Ruger 77/17, sun angle required setting the chronograph farther away from the muzzle. Secondly, different rifles, even of the same make and/or with the same barrel length, are likely to give different velocities anyway.

Two rifles are equally as likely to provide different accuracy results. (As with the B-Mag, the Ruger 77/17 also required semiregular cleaning to obtain consistency and groups that didn’t string horizontally a bit.) Listed here are the averages for four consecutive five-shot groups as applicable to each rifle, with the Ruger’s averages first: 25-grain Winchester, 1.186/1.323 inches; 20-grain Winchester, .765/1.207 inches; 20-grain Hornady, 1.083 inches.

Like the B-Mag, the Ruger test rifle proved quite accurate as tuned, and the cartridge appears to be about perfect for the jackrabbits lingering not so obscurely in the Arizona highlands.