222 Remington

Testing Loads with a 1966 Sako L461 Vixen

feature By: Mike Thomas | April, 16

As for factory ammunition, the 222 Remington filled a sizable gap in the cartridge lineup. Varmint hunters found the new cartridge effective out to around 250 yards or so, far outdistancing the practical range of the 22 Hornet and similar, small cartridges. It lacked the long-range capability (and attendant drawbacks) of the 220 Swift, but the 222 Remington was adequate for most varminting use.

Formal benchrest shooting was still in the formative stages in 1950 when Walker began using the cartridge in competition. Initial results were more than promising. The 222 Remington eventually became and remained a mainstay benchrest cartridge well into the 1970s. To some extent, it is still used today. Handloaders also found great appeal in the comparatively small cartridge that had distinct advantages over other cartridges of the period. The 222 Remington offered a high degree of accuracy, low recoil, fairly mild report, and it did not require much in the way of a powder charge.

My earliest Gun Digest (1952) shows two Remington loads available, one with a 50-grain softpoint spitzer, the other a 50-grain “metal-cased” bullet. Listed muzzle velocity was 3,200 feet per second (fps) for each; trajectory and downrange ballistics were identical. The cartridge was chambered in Remington’s new Model 722 bolt action.

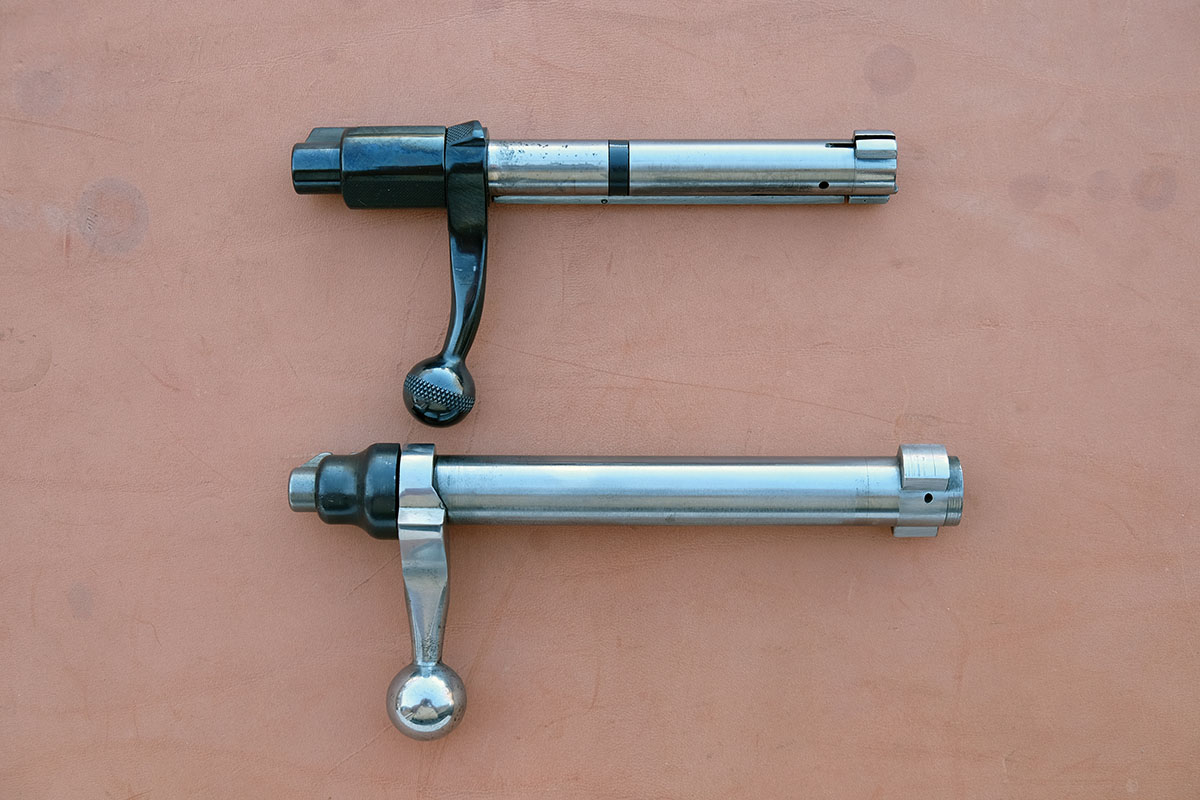

Many shooters agree that a big draw for the L46 was its compact action size. Comparatively, the action weighed around 32 ounces versus 40 ounces for the Remington 722. Receiver length was almost an inch shorter for the Sako, at slightly over 7.0 inches. Bolt diameter for the Remington was .700 inch, while the Sako was only a bit over .5 inch. In fairness to Remington’s 721/722 rifles, the basic design was originally built for use with much larger cartridges.

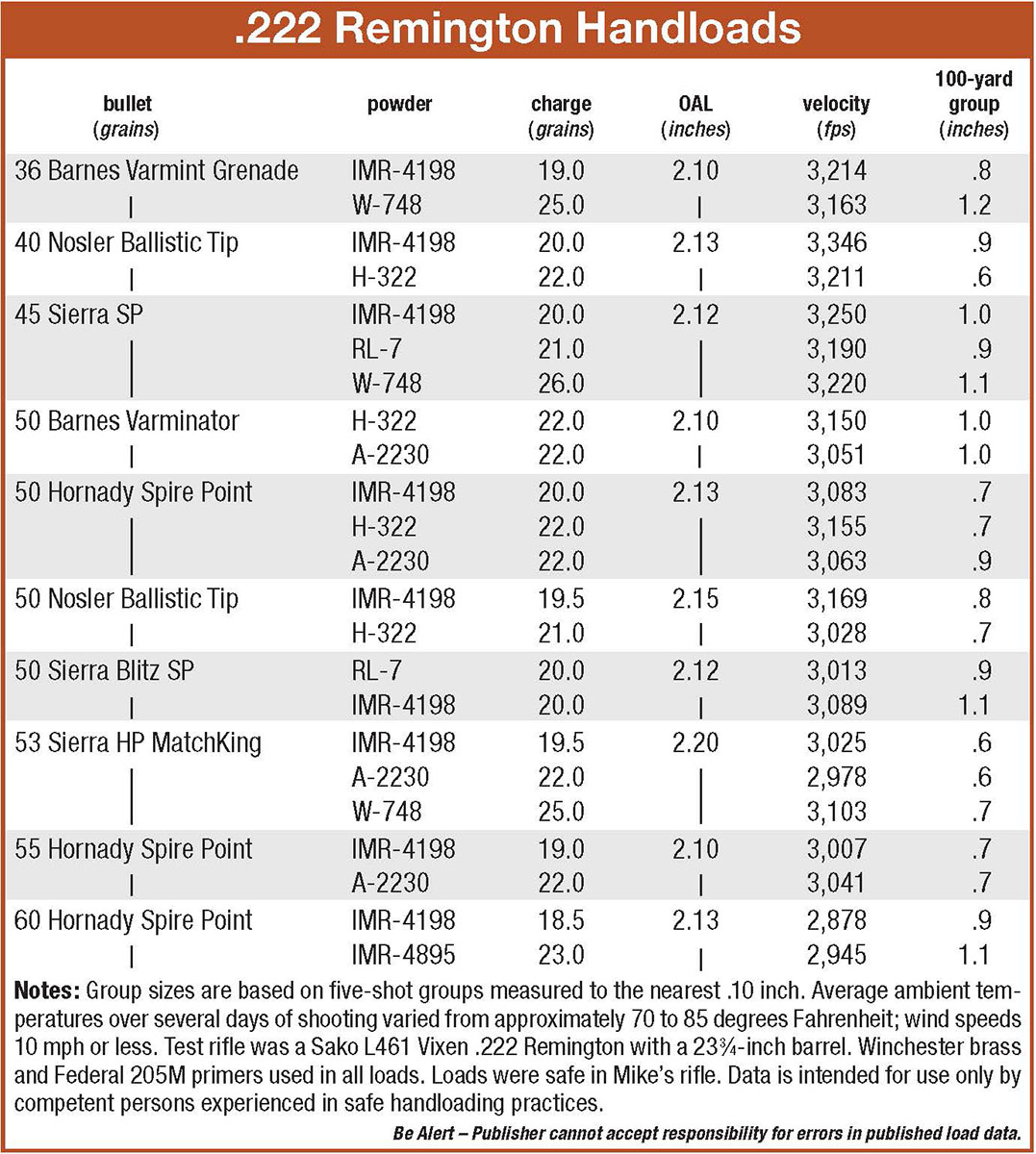

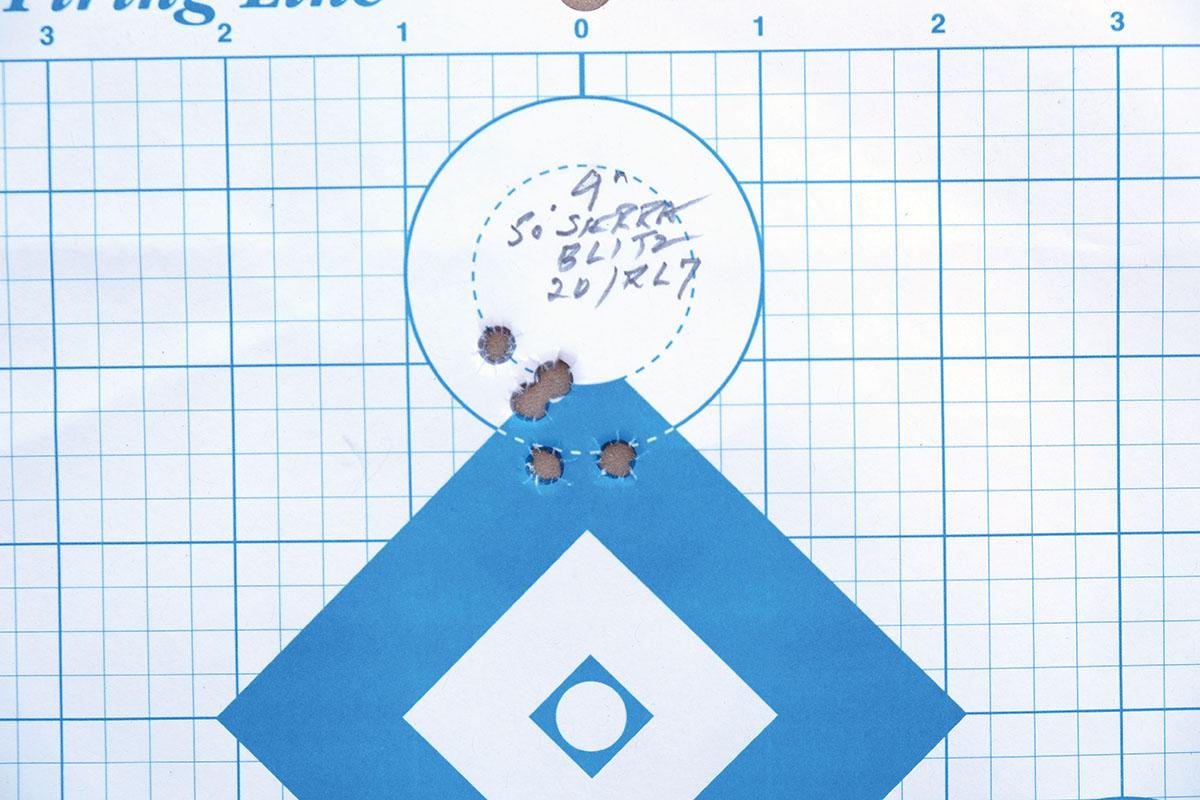

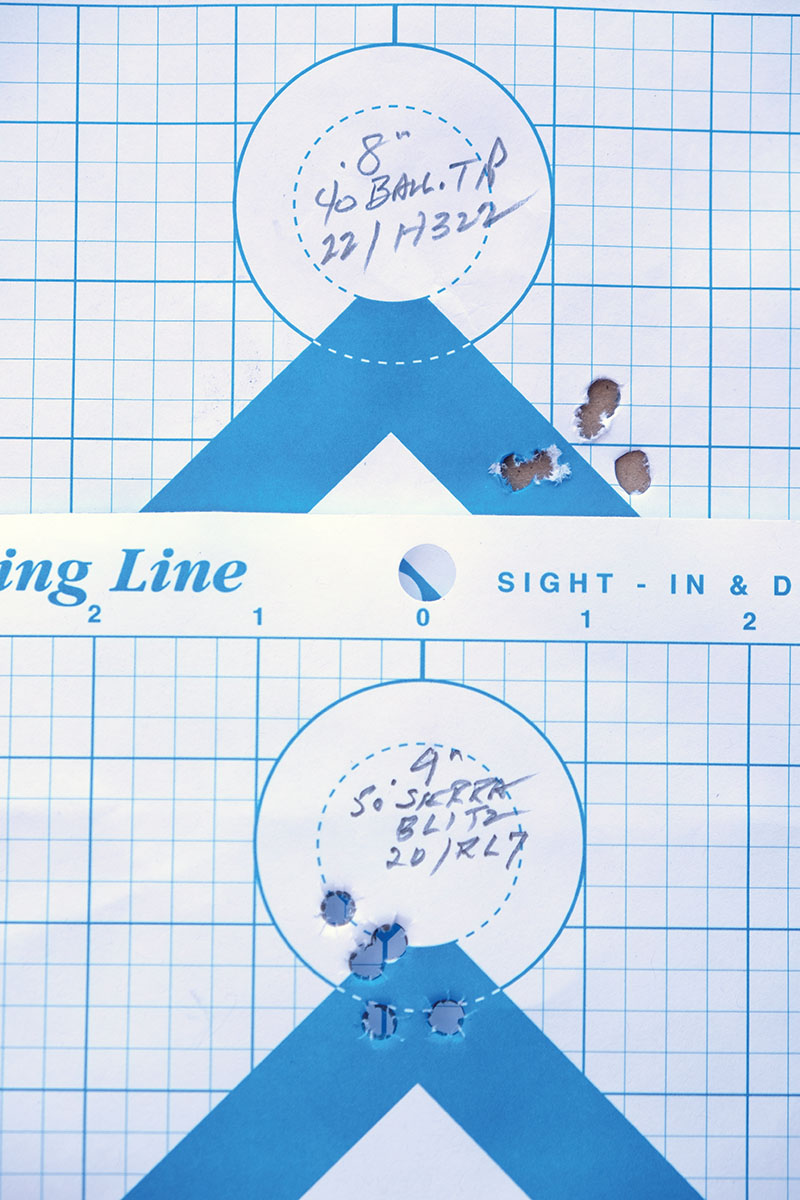

For several years, beginning in 2000, I lived in a rural area of North Texas just below the Oklahoma (Red River) border. From the back porch, shooting coyotes in an open field as they traveled from one wooded drainage to another became commonplace. One of two rifles was usually kept handy: a 219 Zipper built on a Krag action or a Ruger bolt-action 223 Remington. After getting to know some local folks in what was found to be a very gun- and hunting-oriented community, I discovered many native residents used Sako 222s for everything: coyotes, bobcats, feral hogs and deer. I’m not recommending the 222 Remington for wild pigs and whitetail, but the locals voiced no complaints using their favorite handload, a 50-grain Sierra softpoint and 20.5 grains of IMR-4198. Sierra’s data manual calls this a maximum load with a muzzle velocity of 3,200 fps.

Eventually a 222 Remington was desired, and the first one I found was a Remington Model 722. In what appeared to be unused condition and at a fair price, the rifle was purchased and a period Weaver K-6 scope was installed. Several hundred rounds of load development showed the rifle was accurate with most any load, which led to a “need” for a Sako version. Soon afterward, I made my regular weekly pilgrimage to the shop of long-time Nocona resident gunsmith Elton Teague. Elton had recently acquired a pristine 1966 Model 461 Vixen 222 Remington, and it was for sale. The gunsmith had been a Sako 222 advocate since the 1960s. To shorten the story, after a few minutes, I was no longer a village outsider. An older 6x Leupold Compact scope that had been on several other rifles was mounted on the Sako. Of course, it was accurate.

Some months later, I stumbled upon a Sako 46 222 Remington made in the mid-1950s. It shot so well with the Sako aperture sight in place that it has not been scoped. Less than a year after purchasing the first Sako, another 46 (circa 1960) came along. A second, well-used Leupold 6x Compact scope was placed in its rings/mount system. The bore had very slight pitting and fouled more quickly than most barrels, but it shoots well enough.

While on the subject of barrels, a couple of important points bear mentioning. There seems to be a bit of controversy over barrel twist rates in the Sako 222s. There has been a change or two over the years and some disagreement as to when they occurred. I set out to find the twist rates of my rifles, only to realize the easiest way to get reliable information was to take the measurements myself.

The early L46 has a one-turn-in-16-inch twist. It shoots accurately with Sierra 50-grain Blitz bullets and probably will with most other conventional 50-grain bullets of similar length. By “conventional,” I refer to a lead-core, jacketed softpoint or hollowpoint bullet rather than a monometal bullet or a long,

Another point worthy of comment has to do with bullet weights in the 222 Remington. In the late Bob Hagel’s book Guns, Loads & Hunting Tips (Wolfe Publishing) is an interesting chapter regarding extensive test work he did with the cartridge. Hagel used two Remington 40X target rifles. One of the important aspects noted was that bullets under 55 grains were generally more accurate. I was skeptical so did some informal testing. After comparisons using not only the 222 Remington but also larger .22 centerfire cartridges, including the 220 Swift, I must agree with Hagel’s conclusions. Of course, with some rifles (and not necessarily because of the one-in-14-inch twist rate), this supposition may not hold true. It may take a very accurate rifle to see any difference at all.

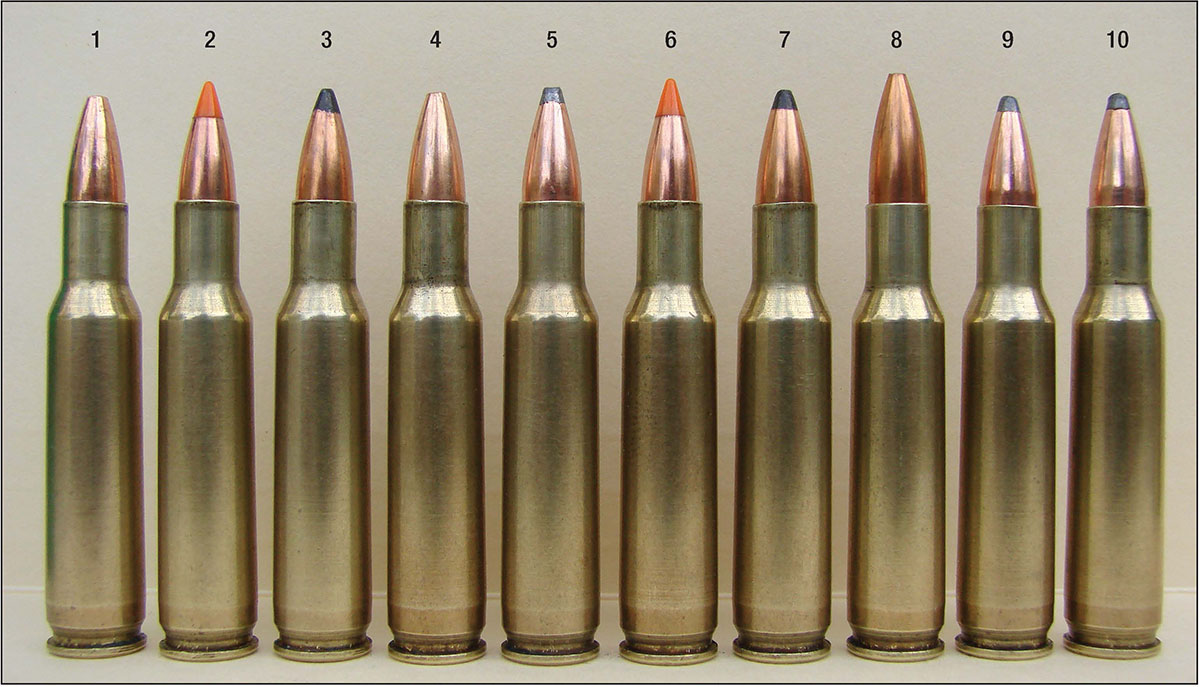

Since this endeavor was also intended as a handloading project from the start, 10 .224-inch bullets ranging in weight from the Barnes 36-grain Varmint Grenade to Hornady’s 60-grain Spire Point were selected. I had never tried some of these bullets in the 222 Remington and did not use a number of bullets that I had experience with. Bullets included in the accompanying load table cover the greatest part of the weight spectrum for those suitable for the cartridge.

Some of the chronographed velocities obtained seemed a bit high in some instances, perhaps due to a “fast” barrel. An Oehler 35P chronograph was used in recording all data. The Sierra 53-grain HP MatchKing is a target bullet. While it is accurate in almost any rifle, Sierra recommends against using this and any other Sierra target bullets for varmint shooting. Expansion is not reliable, and I found this out firsthand years ago when I didn’t know any better. It worked on coyotes only about half the time.

The Winchester brass used for developing the load data had an average unprimed weight of 92 to 93 grains. Another, newer lot of brass averages about a grain more – virtually no difference. Some older Winchester brass on hand averages a full 10 grains less – a significant difference. A cursory comparison revealed that muzzle velocity using the same charges in the light and heavy cases varied by about 100 fps, with the advantage, of course, going to the heavier brass. Pressures will also be higher.

It was not the most accurate bullet tried, but the Hornady 60-grain Spire Point grouped better than anticipated. Apparently it is compatible (not too long) with a one-in-14-inch twist rate. I did not try for 3,000 fps with this bullet, but according to Hornady’s data, such a velocity is achievable.

Over the years, I’ve had a number of rifles rebarreled – usually high-mileage ones that have lost their accuracy edge. I’ve yet to experience this with any 222 Remington rifle. SAAMI specs call for a maximum pressure of 50,000 psi, considerably less than some other “higher intensity” cartridges. This is likely a contributory factor to greater bore life.

About 30 years ago, someone told me of a heavy-barreled Sako 222 Remington he owned. At approximately 11,000 rounds, accuracy began to fall off. He shot it for another 1,000 rounds and had it rechambered (not rebarreled) to 223 Remington. Accuracy improved to the point that it shot as well as it ever did as a 222. He used one of the 4895 powders (probably IMR) exclusively in his rifle.

Sako no longer chambers for the 222 Remington cartridge. Granted, it’s not popular today and has long been overshadowed by the 223 Remington, to which it is often compared. There is little practical difference between the cartridges from both a ballistic standpoint and a field use perspective. The 222 Remington and the Sako rifles in which it was chambered remain as useful today as they were 65 years ago.