240 Weatherby Magnum

Varmint Loads for a 6mm Hot Rod

feature By: Jim Matthews | April, 16

Even when all that is pointed out, most varmint hunters will snort at the idea of a 240 Weatherby Magnum as a viable varmint hunting option. For sure, part of the problem is that 240s are only available in Weatherby Mark V and Vanguard rifles (or custom rifles), limiting choices. Well, that may not be as large of a problem these days. A recent count in Weatherby’s 2016 catalog reveals there are 23 different rifle configurations available in the 240 Weatherby Magnum – from medium barrel contour versions that function well as varmint rifles to ultra-lightweight mountain rifles that make excellent walking varminters. Rifle limitation is hardly a drawback.

Other comments heard about the 240 Weatherby Magnum are that it’s expensive to shoot, it is overbore, and it doesn’t offer that much more performance over other 6mm factory rounds on the market. Yes, Weatherby or Norma 240 brass is more costly than 243 Winchester brass, but in the scheme of varmint hunting, that cost is really a small part of the equation. The expense of brass is far less (especially when considering time involved) than making 6mm-284 or 6mm-06 wildcat brass.

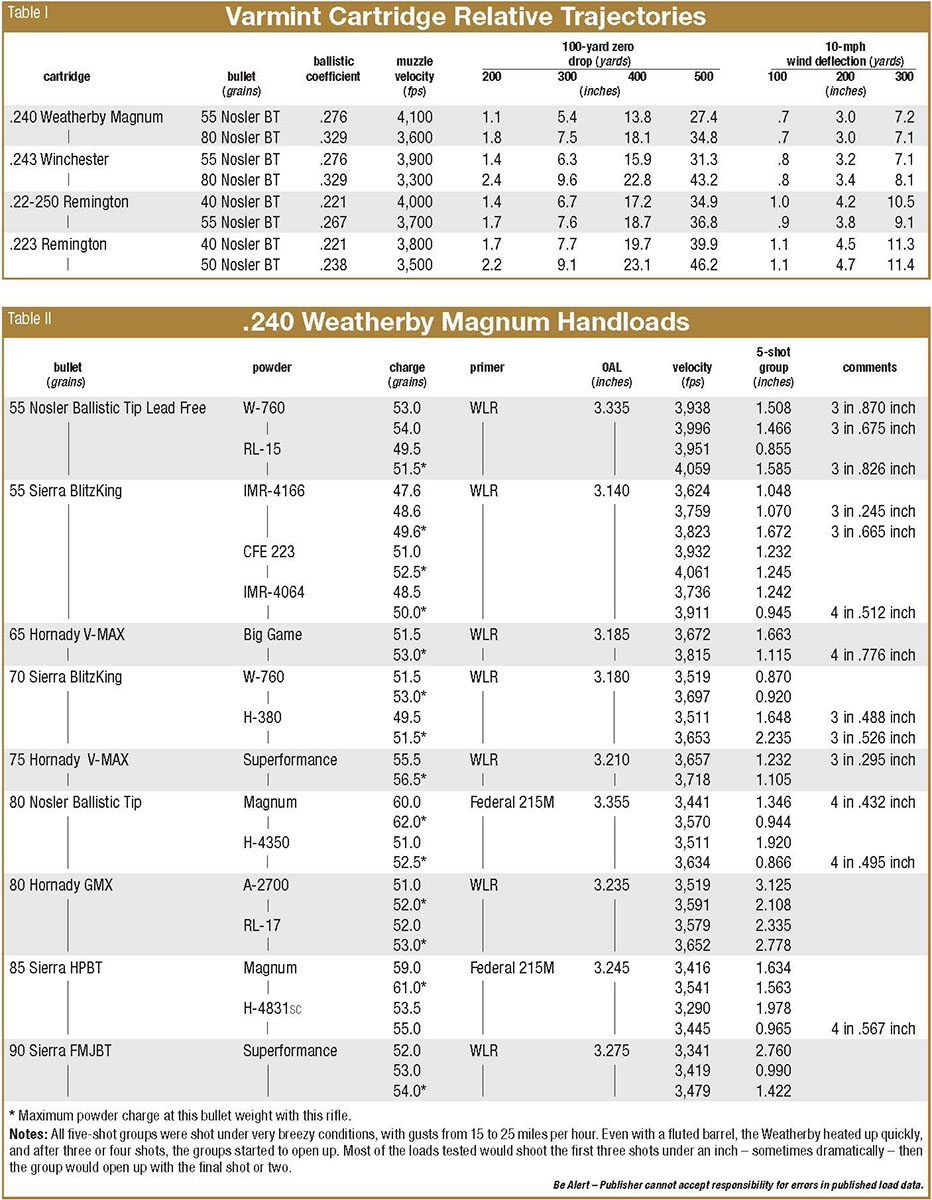

The whole performance argument doesn’t hold water either. If a step up in performance is preferred, you pay

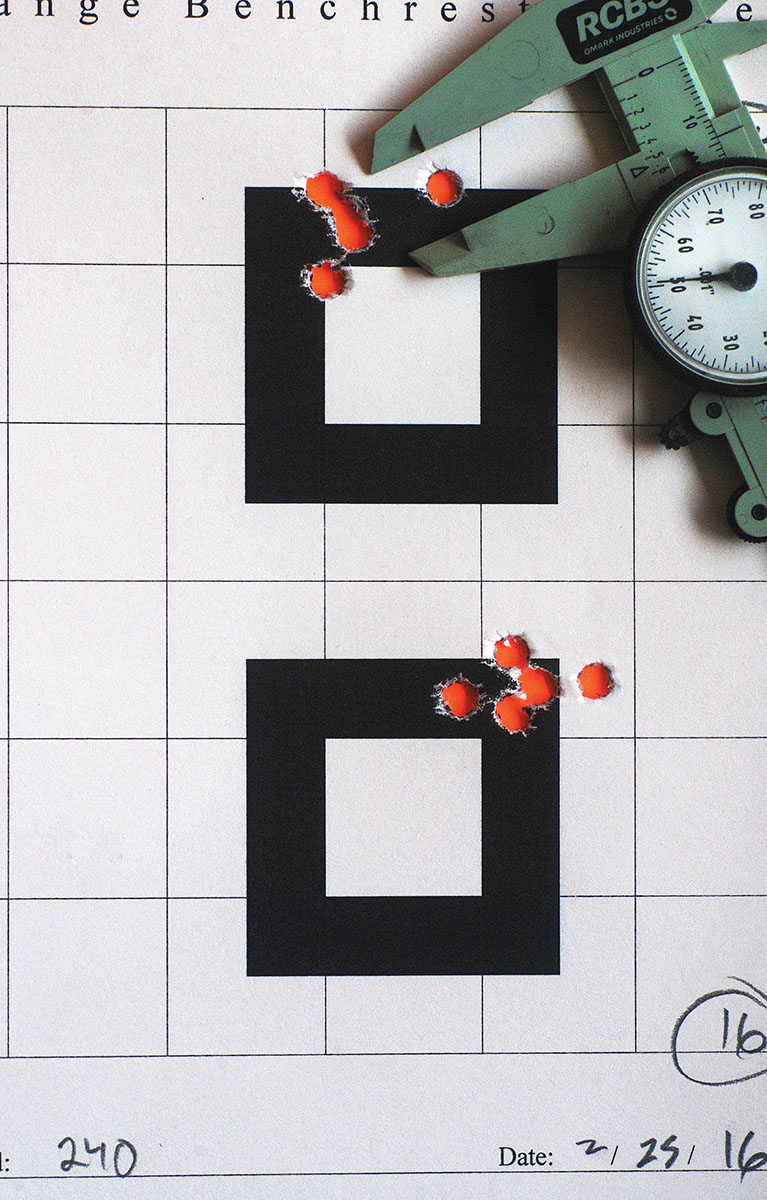

Another important question is potential accuracy. The test rifle used for the handloading data (Table II) was a Weatherby Vanguard Accuguard SS with a 24-inch fluted, stainless barrel and action with a composite stock fitted with an aluminum bedding block. The barrel also has a recessed target crown. This rifle comes from Weatherby with a guarantee of sub-MOA, three-shot groups at 100 yards with Weatherby factory ammunition. Nearly every handload shot through the rifle met that criteria, even in horrible, windy shooting conditions during four days of testing bullet and powder combinations.

Weatherby calls the fluted 24-inch barrel a No. 3 contour (.730-inch muzzle diameter). It heated up quickly, and groups opened up as a result, but the barrel also cooled down fairly quickly, and I was able to shoot groups 15 minutes apart. The reality is that nobody buys or puts together a hot-rod, 6mm-caliber rifle to blaze away in a prairie dog or ground squirrel colony; such rifles are used to take that long poke at a ground squirrel that is sitting up at 300 yards when the breeze starts to kick up. It is used for big woodchucks or rockchucks that have lumbered out on a rock across a big meadow. You use one of these rifles to smack that educated coyote that won’t come into the call any closer and starts loping away at 350 yards. High-velocity 6mm cartridges have an advantage at distance and in windy conditions. The versatility provided during big-game seasons is a bonus.

To fit the Weatherby marketing mold, the 224 Weatherby Magnum surprised many riflemen. First, the cartridge was built on a scaled-down, belted case with a unique head size that was slightly smaller than the standard 30-06-308 head size (.430 versus .472/.473 inch). Second, this cartridge had nearly identical ballistics to the 22-250, making it the only Weatherby offering at the time that didn’t lay claim to the highest velocity for its caliber in a factory loading. Only dyed-in-the-wool Weatherby fans own 224s, and you can’t find one in the current catalog.

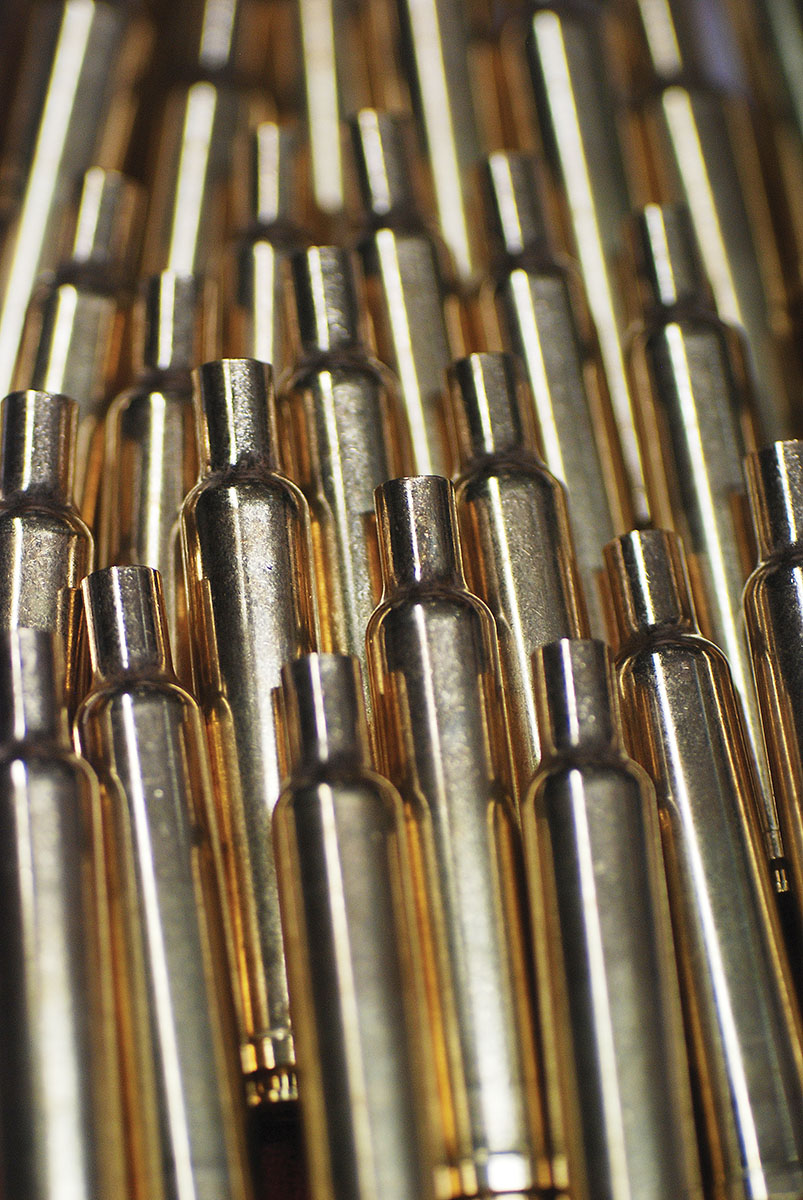

Weatherby’s efforts on the small end of the caliber range continued, however, and the 240 Weatherby Magnum was finally introduced in 1968. Not really surprising anyone, the cartridge was also built on a unique belted case – but not with the same head size as the 224 Weatherby Magnum. The 240 Weatherby Magnum is basically a belted 30-06 case with the radiused shoulder found on all Weatherby cartridges. On one hand, this can frustrate handloaders, because they can’t readily make the brass from other cases (just as with the 224 Weatherby Magnum). On the other hand, loaded ammunition and brass were available even during the crazy ammunition and component shortages of the last few years.

The fact that the 240 Weatherby Magnum was essentially the same size as .270 and 30-06 class rounds made it ideal to chamber in the Vanguard action series of rifles made for Weatherby by Howa since 1971 and continuing to this day. The introduction of Weatherby’s 240 into the Vanguard line in 2012 has boosted the interest in this round. When it was only available in the Mark V, 240s were a relatively expensive option, but a varmint hunter can pick up a Vanguard 240 Weatherby Magnum for less than $650 (suggested retail) and often much less than that in the real world.

Testing the Vanguard 240 Weatherby Magnum was a trip down memory lane. I am part of a generation of now-aging shooters and hunters who grew up with 243 Winchesters and 244/6mm Remingtons not long after they were first introduced. When the 243 Winchester and 244 Remington both arrived on dealer’s shelves in 1955 (6mm Remington, 1963), they were almost instantly accepted by the shooting and hunting public. For a lot of hunters, a .24 caliber was our first centerfire rifle, and we used them for everything from varmints to lighter big game. They were versatile, light-recoiling and accurate.

Almost overnight, the sales of 6mms outpaced the .25 calibers in the same ballistic class. This was simply due to the fact that 6mms were “perfect enough” for the kind of game most hunters in this country pursue – deer and varmints. As modern cartridges, the .24s were factory loaded to higher pressures and velocities than the 250 Savage or 257 Roberts and looked far superior on paper.

My first rifle was a Winchester Model 670 243 Winchester with a Weaver K6 scope. That rifle, the cheap push-feed version of the Model 70 with a plain hardwood stock, accounted for my first couple of deer and claimed the longest shot I’d ever made on a varmint, a 400-yard plus poke made on a California ground squirrel, the distance measured with the odometer on a Volkswagen Bug then calculated to yards.

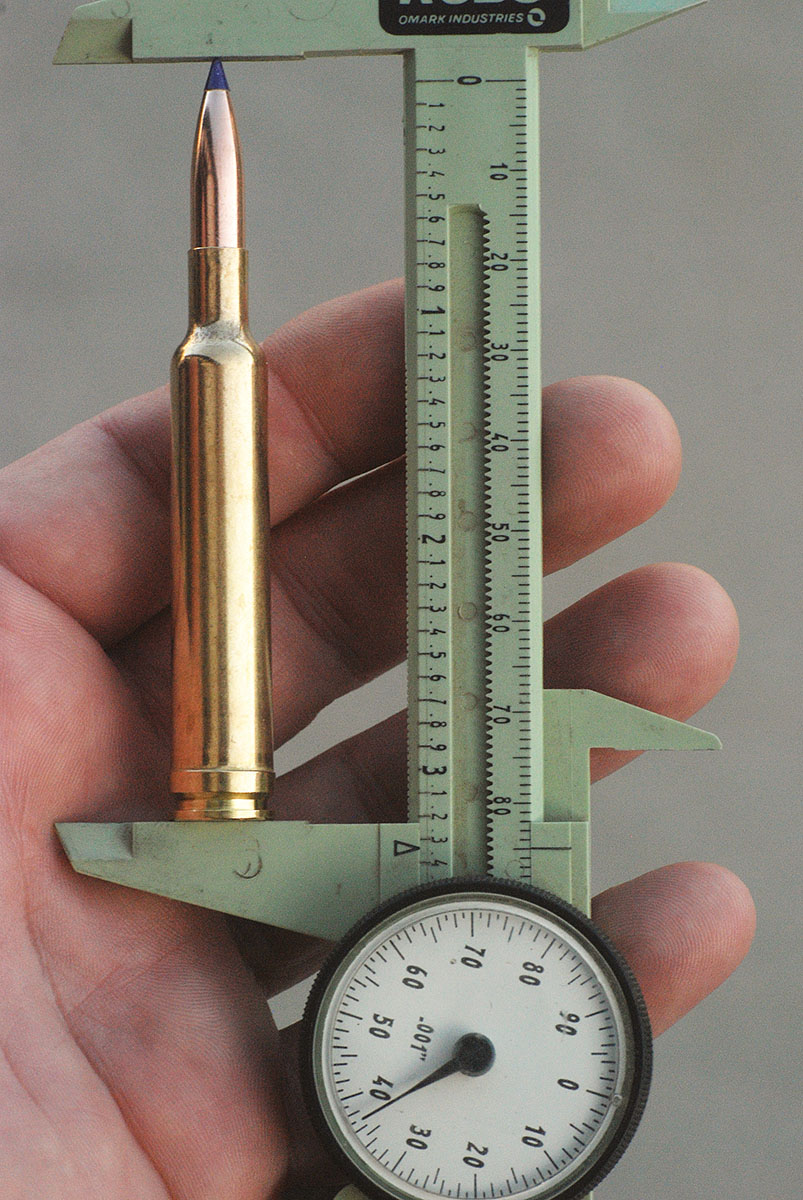

When the 240 Weatherby Magnum arrived for testing, handloading focused on the light end of the bullet weight spectrum for varmint hunting. Both familiar powders and some of the newer powders were used. The first time the Oehler 35P chronograph ratcheted out a 4,000-plus velocity number on the little printer, I stared at it a long time. That is just not a number you see every day.

Of note, virtually all loads listed in Table II have overall cartridge lengths longer than those listed in the current handloading manuals I have on hand, which indicate roughly 3.1 inches. The Weatherby Vanguard tested had an internal magazine length of nearly 3.5 inches and, like the Mark V rifles, its chamber throat is freebored, making it impossible (with lightweight varmint bullets) to seat a bullet far enough out of the case to be close to the lands. The lightest projectiles were seated deeply enough to have approximately 1⁄8 inch of the bullet inside the neck. All the loads in the table functioned through the magazine of the Vanguard. Additionally of note, some of the powder charges listed in the data are indicated as “maximum” for this specific rifle, and handloaders should reduce powder charges accordingly when beginning to work up a load.

While wrapping up the testing of handloads, I stole away with the Vanguard 240 Weatherby Magnum for a few minutes and shot another ground squirrel off that same distant rock where I’d killed my “longest squirrel” those many years ago. The shot was made from a rock pile a bit farther than from where the 243 Winchester shot was taken, and this time the distance was measured with a laser rangefinder instead of an odometer. It was 437 yards.