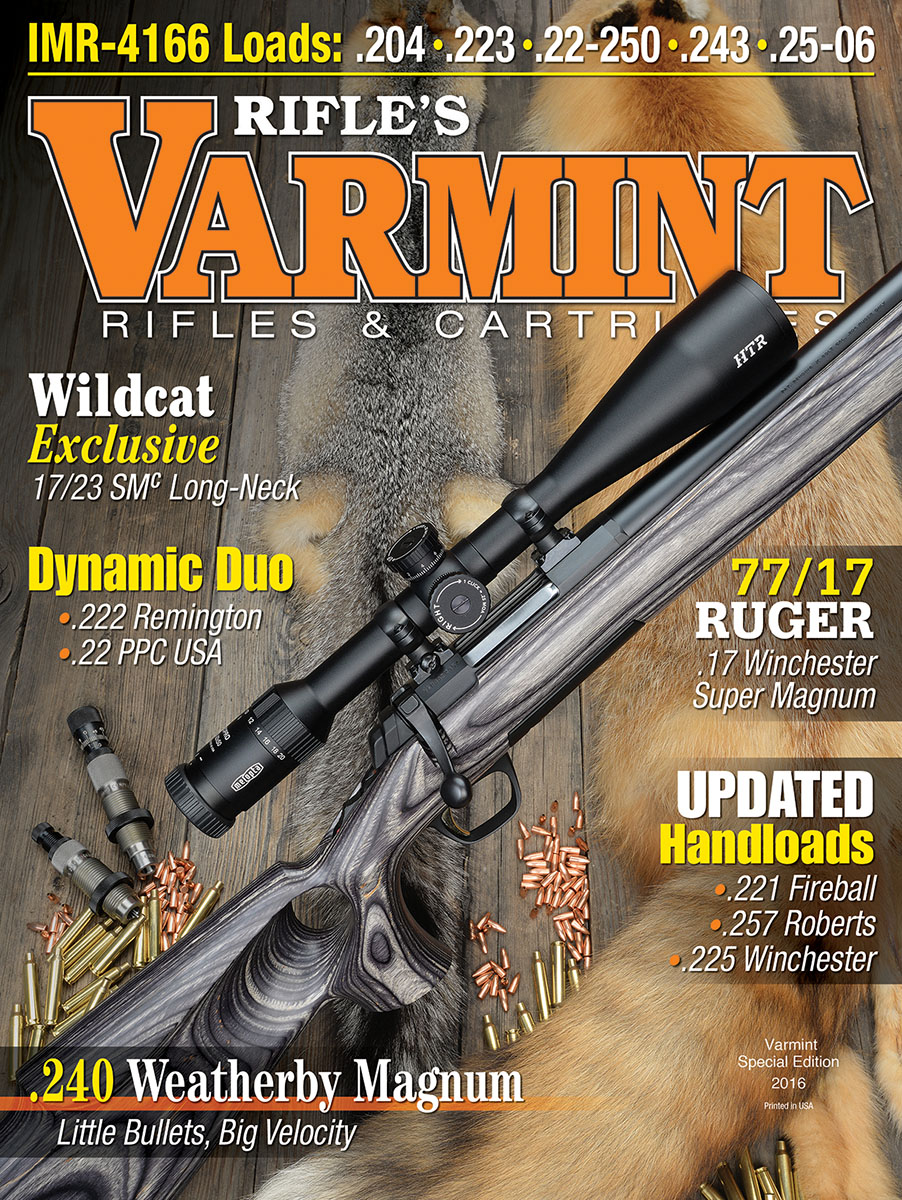

IMR-4166

Loads for Five Varmint Cartridges

feature By: John Haviland | April, 16

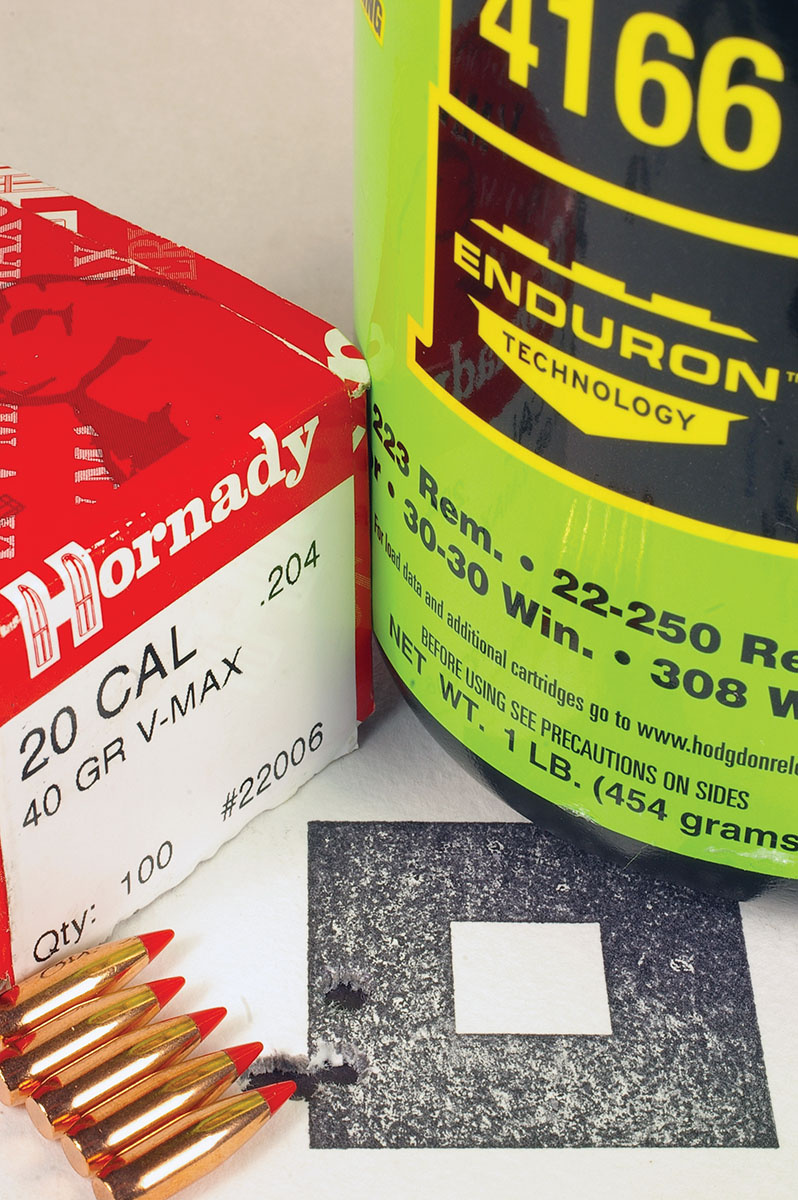

Varmint hunters are relentless experimenters, always searching for that superior load for rifles that squeezes the last dash of velocity from a cartridge and accuracy out of bullets to shoot the nap off a gnat. IMR-4166 is one powder handloaders should consider testing, because it contains several advantages from what Hodgdon calls Enduron Technology.

One of those benefits is 4166 produces unchanging velocities over a range of temperatures. Another is an additive that prevents copper fouling from building up in rifling to provide longer periods of accurate shooting and less scrubbing and soaking to clean a bore. A third is bulk density. A case nearly full of powder and then slightly compressed when a bullet is seated keeps the powder column in a fixed position to help provide uniform velocities and good accuracy. These features are just what varmint hunters are looking for to improve our handloads. In that vein, IMR-4166 was loaded with a variety of bullet weights in cartridges from the 204 Ruger to the 25-06 Remington.

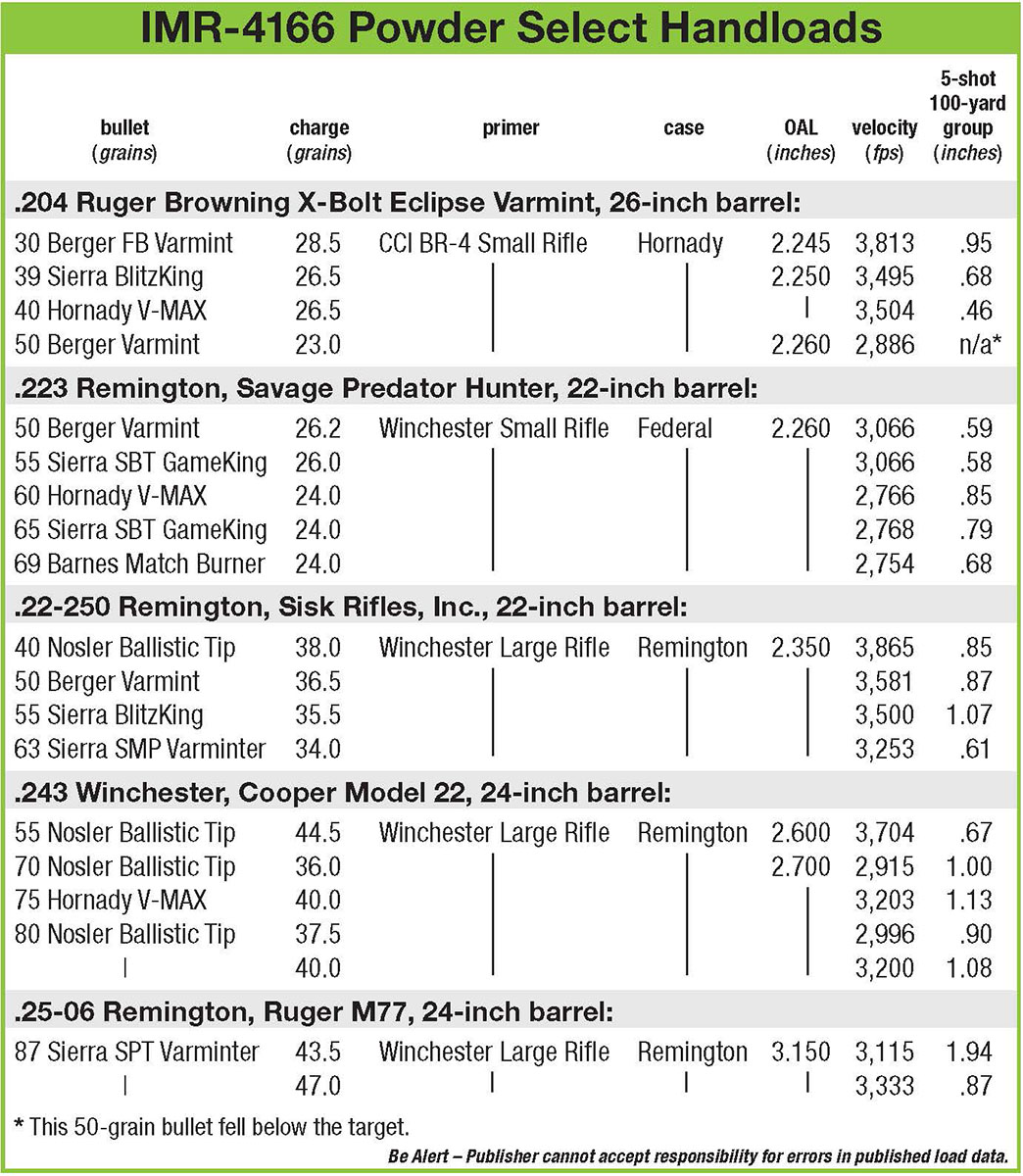

A varmint shooter burns through a lot of cartridges during a day in a field swarming with ground squirrels. Dispensing powder from a measure right into cases certainly reduces the time and toil at the bench reloading cartridge cases. IMR-4166 is a fine-grained, cylindrical powder, and to test how smoothly it flowed through my Ohaus powder measure, the measure was set to dispense 35.5 grains of 4166 for my 22-250 Remington. Over five cycles of the measure, charge weights varied only 0.1 grain. A 243 Winchester load of 37.5 grains of IMR-4166 with a Nosler 80-grain Ballistic Tip, listed in the load table, was dumped from the measure into cases. The pair produced a standard deviation (SD) of velocity of 18 fps, slightly lower than weighed charges of the same amount of 4166.

The only problem with dumping IMR-4166 from a measure occurred with 204 Ruger cases. The powder’s extruded grains often wedged in the 204 cartridge necks, and the charge remained in the funnel. I kept an eye on the funnel, and when the powder clogged, jiggling the case allowed it to flow in.

IMR-4166’s relative burn rate sits between IMR-4895 and Accurate 2495 on the fast side and IMR-4064 and Alliant Reloder 15 on the slow side. That makes IMR-4166 nearly ideal for the 204 Ruger, 223 Remington, 22-250 Remington and for shooting lighter-weight bullets in the 243 Winchester and 25-06 Remington.

The 204 Ruger is chambered in the Browning X-Bolt Eclipse Varmint rifle with a 26-inch barrel. My Ruger M77 25-06 Remington is a 40-year-old rifle with a new Lilja barrel with about 200 rounds fired from it. The three other rifles used to test IMR-4166 have been shot a lot. The majority of that shooting was directed at prairie dogs and ground squirrels and heated the barrels enough to blister fingers. These three rifles, a Savage Predator 223 Remington, a custom Sisk 22-250 Remington and a Cooper Model 22 243 Winchester, have some erosion in the throats of their rifling, but they are still very accurate.

Shooting commenced on a winter day with a temperature of 30 degrees. A temperature inversion had settled over the valley, and the air was dead still. I fired a few three-shot groups through each rifle to make sure they were properly sighted in at 100 yards and to blow out any oil or cleaning solvent in their barrels. A five-shot group was fired with each load listed in the accompanying table. After shooting a group, I switched to another rifle to allow barrels to cool. A given rifle’s barrel was freezing cold when its turn to shoot arrived again.

One of IMR-4166’s advantages is it produces unchanging velocities over a range of temperatures. I considered heating up ammunition to 90 degrees to compare its velocity to cartridges fired at 30 degrees, but keeping cartridges from cooling would be nearly impossible during the 20-minute drive to the range. Plus, taking five cartridges from a cooler filled with heat packs would further cool the cartridges before they could be fired. The exact temperature when a cartridge was fired would be unknown. In addition, the rifle would be cold, not warm like in the summer. So I’ll defer to John Barsness’s article on IMR-4166 in the Hodgdon 2015 Annual Manual. Barsness put ammunition in a 0-degree freezer overnight then shot it the next day. He wrote “. . . none of the frozen ammunition lost any significant velocity” compared to ammunition fired at 85 degrees. “In fact, the 223 and 45-70 ammo actually chronographed slightly faster than at 85 degrees . . .”

Maximum charges of IMR-4166 are compressed when a bullet is seated in some varmint cartridges. The Hodgdon 2016 Annual Manual lists compressed powder charges for IMR-4166 loaded in the 204 Ruger with 26- to 35-grain bullets, the 223 Remington loaded with 53- to 60-grain bullets and the 22-250 Remington assembled with 40- and 50-grain bullets. No doubt a caseful of powder provides uniform velocities, but bullets heavy for their caliber also provide more uniform velocities than lighter bullets.

Standard deviations of velocity from the 204 Ruger shrank as bullet weight increased; so did group size. Fifty-grain bullets provide a pretty good ballistic balance for the 223 Remington. With that weight and heavier bullets, IMR-4166 turned in small SDs from the loads shot through the Savage 223 rifle. All five loads grouped tightly. The 22-250 Remington also produced low SDs with 4166, and those fairly well decreased as bullets got heavier. The 243 Winchester generated a rather high SD shooting 55-grain bullets, but SDs were much lower shooting heavier bullets. The 25-06 Remington shot a low SD of 15 fps with a near maximum load of IMR-4166.

My 25-06 Remington is used mainly to hunt big game and to that end includes a Leupold VX-3 2.5-8x 36mm scope. With the scope turned up to 8x, it’s difficult to see a marmot peeking over a boulder or a ground squirrel hunched by its burrow much past 250 yards. So there is little sense shooting a fire-breathing load through the rifle for short-range shooting, but reduced amounts of some powders often produce wide swings in velocity, and bullets string vertically.

The 43.5-grain charge of IMR-4166 is 0.3 grain above the minimum Hodgdon lists for 87-grain bullets for the 25-06. That amount of powder produced a 30-fps velocity spread and an SD of 12 fps for five shots with Sierra 87-grain bullets from my rifle. There was a bit of vertical spread to the five-shot group, but the velocity spread and SD were less than with a near-maximum load of 47.0 grains of 4166.

Reduced velocity loads with IMR-4166 also worked well with the 243 Winchester. Thirty-six grains of 4166 is 2.5 grains below the minimum charge listed for 70-grain bullets in the Hodgdon manual for the 243 Winchester. Still, the velocity spread from that powder charge was an acceptable 41 fps with five Nosler 70-grain Ballistic Tips shooting a one-inch group at 100 yards. Another reduced load for the 243 consisted of 37.5 grains of IMR-4166 paired with Nosler 80-grain Ballistic Tips. The pair produced an SD of 18 and a .90-inch group at 100 yards. That was a slightly low SD and tighter group than a near-maximum charge of 40.0 grains of 4166 with Ballistic Tip bullets.

My loads with IMR-4166 came up quite short of the velocities listed in the Hodgdon reloading manual. Some of that disparity can be explained by the 22-inch barrels on the 223 and 22-250 test rifles, while Hodgdon used 24-inch barrels. The larger chambers in commercial barrels compared to test barrels also play a role. Certainly throat wear contributes, as well as loading with different cases, primers and bullet brands. Still, the 200 fps slower velocities from the 223 Remington, 22-250 Remington and 243 Winchester are puzzling.

Before leaving the range, I shot up the remaining cartridges loaded with IMR-4166 in the five rifles. All told, four of the rifles had been used to fire about 50 rounds apiece. The Savage 223 Remington had fired 70 rounds. At home, I was sure hoping the additive in 4166 that prevents copper fouling from building up in rifling would help speed cleaning the Savage. It has always been a very accurate rifle, even though its bore looks like a washboard gravel road. The powder and bullet jacket fouling that accumulate in the ruts and furrows in the bore are impressive.

Several patches, soaked with citrus cleaner, were pushed through the Savage’s bore to clean out most of the powder fouling. Peering into the bore with a Lyman Digital Borescope showed long streaks of copper fouling on the rifling lands and some in the grooves. My usual method to clean the bore is to squirt it full of Gunslick Foaming Bore Cleaner, plug the muzzle with a foam ear plug and let it soak for two days. This time I squirted in Gunslick and came back an hour later. A few dry patches pushed through the bore came out dirty. A fourth was fairly clean. A patch, soaked with Montana X-Treme Bore Solvent, pushed through the bore came out with only a minor streak of blue. The borescope’s monitor showed most of the copper fouling was gone.

The 22-250 and 25-06 Remingtons have Lilja barrels, which are known for their smooth bores. Near as I could tell with the borescope run the lengths of the barrels, there was not a hint of copper fouling in either bore. The bores of the 204 Ruger and 243 Winchester showed some copper fouling, and it was easily removed with solvent-soaked patches.

The cleaning was easy, and instead of scrubbing bores, I was back at the bench sizing cases. Now that all the work developing loads and loading cartridges is completed, I’m enjoying the benefits of IMR-4166 and burning it up in the varmint fields.