221 Remington Fireball

Handloads for a Shortened 222 Remington

feature By: Charles E. Petty | April, 16

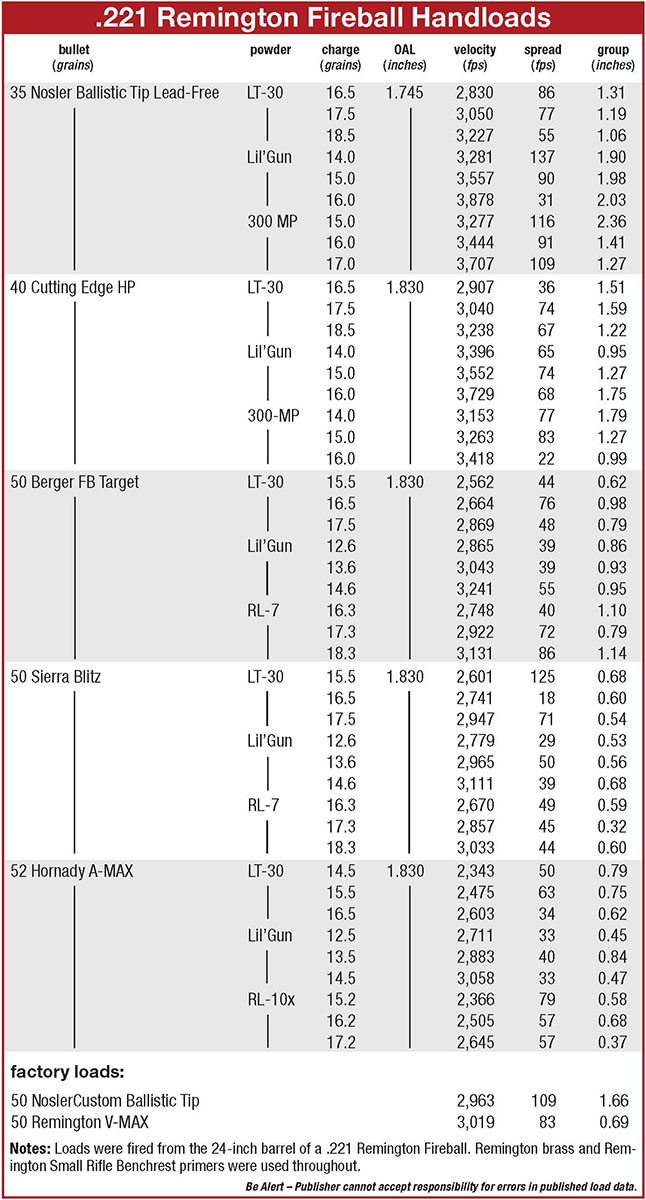

Early handloading results were okay, but I wanted to see if there was any uncharted territory that might be worth trying. A call to Ron Reiber at Hodgdon yielded a couple of suggestions, and then he said, “and you might want to try Lil’Gun.” This was a new ball-type powder intended for use in .410 bore shotguns, often called “little guns” on the skeet field. He sent me a pound.

Because there was no loading data, first I went to the powder burning rate table. Lil’Gun sat right next to H-110 and W-296. Both can be used in cases like the Hornet or Bee, so with that bit of information, it was concluded that, with a 40-grain bullet, a starting charge of 10.0 grains of Lil’Gun wouldn’t cause trouble.

It didn’t. I got all the way to 16.0 grains with velocities that were 200 fps faster than any published data. Fearing I was into never-never land, another call was placed to Reiber. It was less than an hour when he called back and said that not only was my velocity accurate, the pressure was well within SAAMI limits.

That was a long time ago, and now many loading manuals include Lil’Gun, and velocities with other powders are higher too. So for this handloading project, I decided to look at bullets and powders that were not available the first time around.

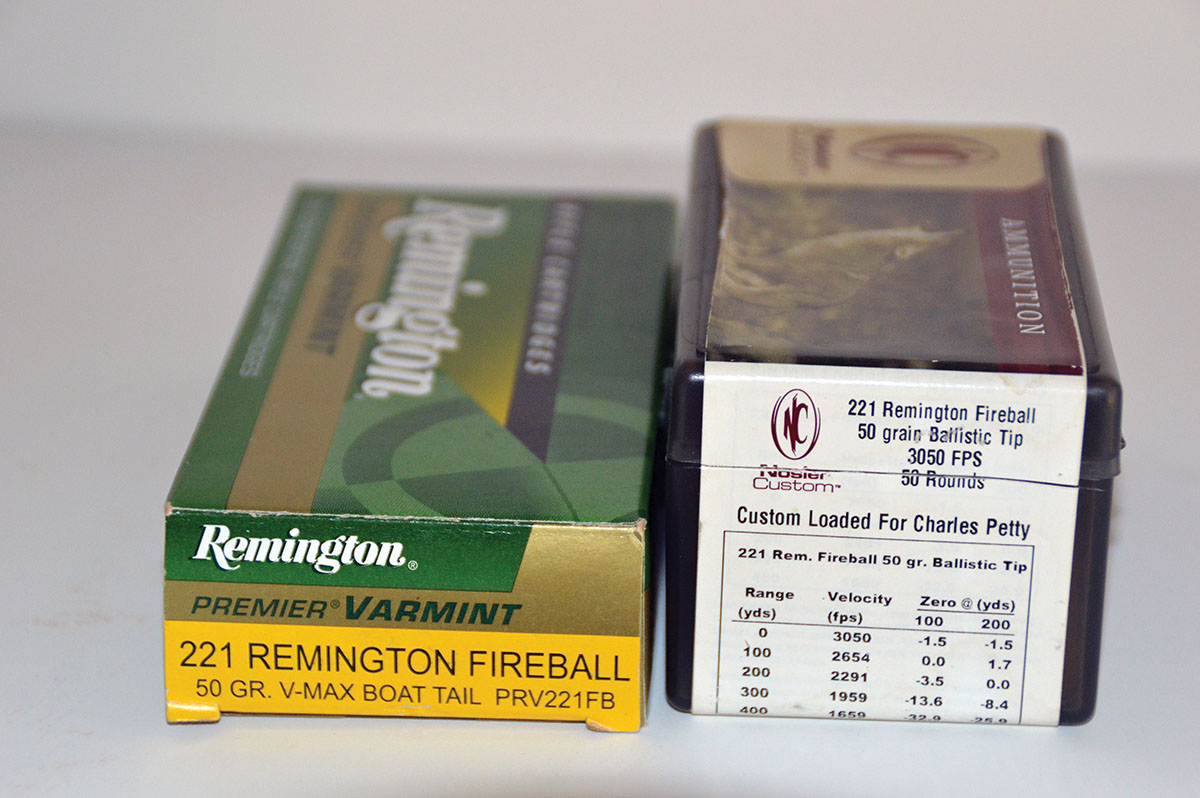

Most of my first 221 Remington Fireball handloads included 50- and 55-grain bullets, and 40-grain bullets were a last-minute addition. I just had time for a basic velocity workup and perfunctory accuracy check, so when planning this test, I made sure to include 35- and 40-grain loads. Powders include Alliant, Hodgdon and Ramshot options and bullets from Cutting Edge, Hornady, Nosler and Sierra. The Cooper Model 21 received a new Leupold VX-3 8.5-25x 50mm Long Range scope.

The 221 Remington Fireball’s small case capacity, roughly 21 grains of water, places limits on the powders used to those toward the faster end of the burning rate chart, and it also limited the spread between starting and maximum loads in the test to two grains. In most cases it was possible to end up with test data in one grain increments.

When testing a lot of rounds, it is easier to divide things into two separate sessions – one to get velocity data and then another to shoot groups. Test charges were established from published sources, except for Accurate LT-30, for which there was no pressure-tested data. Ramshot advised that LT-30 was very similar to A-1680, so those charges were used. Velocities were lower than expected, but in the absence of any pressure tested loads, I was reluctant to go higher.

Test loads were grouped by bullet weight, and a small sample lot of each weight was to allow for sight adjustment, as a significant change was expected between the lighter- and heavier-bullet groups. This wasn’t an issue during chronographing, but when accuracy testing began, issues started with the 50- and 52-grain bullets, and on the next day 40- and 35-grain weights.

Accuracy with 50- and 52-grain handloads was good, but the two factory control loads did not agree, although both used 50-grain bullets. The next day with the lighter bullets, the wheels seemed to fall off. None of them challenged the heavier bullets, and some groups might well have been called patterns. Maybe the best way to summarize is to say that only one load with the lighter bullets shot under one inch (0.95 inch) while only two of the 50-grain loads grouped larger than one inch.

Confessing to limited experience with the lighter bullets, there is no reason to think they are inherently less accurate. The search for answers began with a thorough inspection of the bore and chamber. A borescope revealed sharp cuts for lands and grooves and only a faint smear of copper on top of a few lands. The leade was well defined and showed no erosion.

All brass was neck-sized with Redding Competition dies. Seating was also done with a Redding micrometer adjustable die. All handloads were assembled with weighed powder charges and seated to the overall length shown in the data source. Ammunition for accuracy testing was only loaded in once-fired Remington brass previously fired in the Cooper.

My final conclusion is that the solution is to systematically test accuracy with bullets seated to just touch the rifling and then back off it in 0.005-inch increments. My experience with .22-caliber varmint cartridges is that they will do best either touching or 0.005 to 0.015 inch off the rifling.

Since no two barrels or chambers are absolutely alike, any solution worked out for my rifle may be all wrong for another. Most handloaders measure overall length to the tip of the bullet, but that part never touches the rifling, and if you measure several bullets from the same box, you probably will find differences in overall length. The more accurate way is to measure to the point on the ogive where it does touch the rifling. Hornady has a handy gauge that does this.

The 221 Remington Fireball is a gentle little cartridge that is easy on both rifle and shooter. It doesn’t get super hot over a prairie dog town, and when reading the conditions correctly, shots out to 500 yards or so have been made. The mild recoil lets the shooter recover in time to see the result of the shot and correct as needed.

While I am a fan, the little Fireball takes a beating at the hands of the 223 Remington. That is not to criticize the 223 Remington either, but some of the new powders tried in the 221 Remington Fireball here look very promising and might inspire some new pressure testing. All loads used here showed no signs of high pressure. Bolt lift was easy and primers were not distorted. Still, start low and work up with due care.