218 Bee

Loads for a Classic Cartridge and Rifles

feature By: Layne Simpson | April, 17

When the 218 Bee was introduced by Winchester in the Model 65 lever-action rifle in 1939, many serious varmint shooters had already graduated to bolt-action rifles that had been introduced earlier. Soon after Winchester 22 Hornet ammunition became available in 1930, Griffin & Howe and other shops began offering rifles chambered for the cartridge using 1922 Springfield actions. Winchester began offering the 22 Hornet in its Model 54 bolt gun in 1933, and not long after the Model 70 was introduced in 1937, it became available in 220 Swift. All varmint shooting bases were adequately covered by those rifles and their cartridges.

Whereas lever actions had ruled over the hunting roost for many years, bolt actions had become a serious threat to their supremacy. Ignoring the handwriting on the wall, Winchester decided to give the old levergun

a transfusion by offering new model variations chambered for new cartridges. One was a variation of the Model 94 called the Model 64. It was introduced in 1933 in the usual Model 94 chamberings, and five years later the 219 Zipper was added. On a necked-down 25-35 case, it pushed a 56-grain hollowpoint along at 3,110 fps.

Also introduced in 1933 was a revamped variation of the Model 53 that was a revamped version of the Model 92. Called the Model 65, it was first offered with a 22-inch barrel in 25-20 and 32-20. Those cartridges were joined in 1939 by the 218 Bee that utilized a 24-inch barrel.

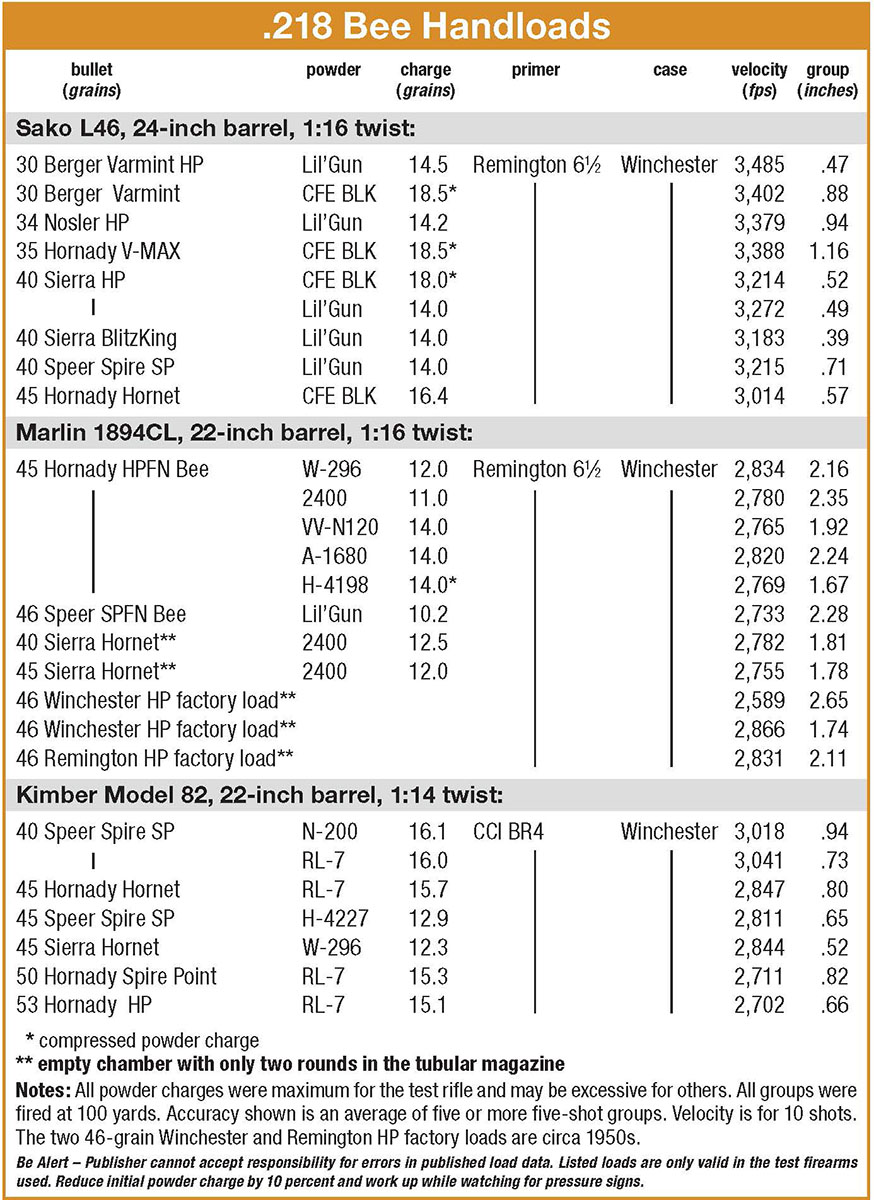

Winchester gave the Bee’s 46-grain bullet a velocity rating of 2,860 fps, which was almost 200 fps faster than the 45-grain bullet of the 22 Hornet. For reasons lost in time, velocity was eventually reduced to 2,760 fps. When 1950’s vintage Winchester and Remington ammunition was fired in my Marlin 1894, it was in the 2,760-fps ballpark of the old loading. Remington dropped the cartridge quite sometime ago, and while Winchester still occasionally loads a round or two every few years, the company has obviously backed off on the throttle. Current ammunition chronographs just under 2,600 fps from the 22-inch barrel of the Marlin 1894.

The Winchester Model 65 was a wonderful little rifle. It carried light, leaped to the shoulder in a flash and spit lead with the best of them. By the time it was introduced, however, varmint shooters had come to expect accuracy, and when compared to Winchester’s Model 54 and Model 70, the Model 65 fell short. Shooters had also become accustomed to using telescopic sights, and the Model 65 only accommodated open or aperture sights.

The most unusual Bee I have examined was the Marlin Model 90. Little did I know at the time that only about 500 were built. Introduced as an over/under, 12-gauge shotgun in 1937, a number of Model 90 variations were eventually introduced, including a combination gun with one of its barrels in 218 Bee or 22 Hornet. It was cataloged as “special-order-only” during 1940. (A Model 90, by the way, was used by Sierra for velocity-testing 218 Bee loads for the company’s present reloading manual.)

In 1989 Marlin added the 25-20 and 32-20 cartridges to the Model 1894CL and followed with the 218 Bee in 1990. Several months prior to those first two introductions, Marlin’s Tony Aeschliman asked me which cartridge would prove to be the best seller. I picked the Bee, and while I was correct, none of those chamberings sold well enough to find a permanent home in the Marlin catalog.

Also during 1989, Browning introduced a Japanese reproduction of the Winchester Model 65 218 Bee. Numbers were limited to 3,500 Grade I rifles and 1,500 High Grade versions. Thompson/Center used to offer the Bee in the Contender Carbine, and it has also been available in the Ruger No. 1.

One of the most accurate Bees I have owned was built by the original Kimber of Oregon during the mid-1980s. Realizing it would not sell in sufficient numbers to justify the expense of converting the detachable magazine of the Model 82 rifle, the company made it a single shot with a solid-bottom receiver. It also had a heavy, 24-inch barrel. The one I should have kept had a rifling twist rate of 1:14 instead of the standard 1:16.

As a historical note, the L46 was also chambered for several other cartridges, including the 7x33mm Sako that was a favorite cartridge of Finnish seal hunters. Very few of those managed to escape from Finland, and most in 25-20 and 32-20 were shipped to Australia. Meanwhile in America, most varmint shooters were choosing the 22 Hornet over the 218 Bee, possibly because the former was factory-loaded with pointed bullets.

Due to the rear locking action of the Marlin 1894, case extraction becomes sticky with some of the loads normally taken in stride by my Sako L46, and while fired cases have to be full-length resized for the lever action, they can be neck-sized only several times for the bolt gun before requiring full-length sizing. I’ll give Winchester credit for this much: Its 218 Bee cases last for many maximum-pressure firings and are quite uniform in both weight and dimension. Though like the ammunition, they are not always easy to find.

There is good news for shooters who own 218 Bees and do not handload: the 2017 introduction of Hornady ammunition loaded with a 45-grain, hollowpoint bullet at 2,760 fps from a 24-inch barrel. The flatnose form of the bullet makes it suitable for use in rifles with tubular magazines. This bullet has been available for handloading for several years and is described in the Hornady manual as 45-grain HP BEE. Unfortunately, the ammunition did not become available in time to be shot for this report. Hornady will also offer unprimed cases.

The 218 Bee case is easily formed from 25-20 Winchester brass by running it through a 218 Bee full-length resizing die. The case will emerge from the die with a secondary shoulder just forward of the original shoulder. Seat a bullet atop a powder charge reduced 20 percent below maximum, fire it in a rifle, and out pops a fully formed 218 Bee case. The neck will be a tad shorter than a factory Bee case, but accuracy is unaffected. The Bee can also be formed from 32-20 brass, but it has to be run through a 25-20 full-length resizer prior to the trip through the 218 Bee die.

The barrels of most 218 Bee rifles have a 1:16 rifling twist, the same as for most 22 Hornet rifles. Kimber Model 82s chambered for those two cartridges have a 1:14 twist. As a rule, 22 Hornet rifles with the slower twist won’t stabilize bullets much longer than .600 inch. Hornady’s 45-grain Hornet is .590 inch long, and due to its semispitzer profile, Sierra’s 45-grain Hornet is shorter at .545 inch. Some of the lighter bullets won’t stabilize because they are longer. Examples are the Sierra 40-grain BlitzKing (.675 inch) and the Hornady 40-grain V-MAX (.687 inch).

What you have just read applies to rifles with a 1:16 twist when the Bee is loaded to equal or only slightly exceed 22 Hornet velocities, but some of the longer bullets will stabilize when pushed faster in bolt-action and single-shot rifles with that twist rate. My Sako shoots the Sierra 40-grain BlitzKing and Hornady 40-grain V-MAX quite accurately, but it won’t shoot the longer tipped bullets weighing 50 grains. Berger recommends a twist rate no slower than 1:15 for its 30-grain FB Varmint bullet, yet five of them snuggle quite closely together when fired from my Sako. Average length of that bullet is .613 inch. The 1:14 twist of the Kimber rifle stabilizes heavier bullets, but even when pushed to maximum velocities, they don’t expand as explosively on varmints as those of lighter weights.

Bullet choices are far more limited for lever-action rifles, because bullet companies warn against using sharply pointed bullets in their tubular magazines. When carrying a rifle with its chamber empty, it is safe to load two (and only two) cartridges with pointed bullets in the magazine. Due to their short lengths, the Sierra 40- and 45-grain Hornet bullets are the best choices available for double-shot loading. The only tube-magazine-friendly bullets I am aware of are the Hornady 45-grain HP BEE and the Speer 46-grain SPFN. The former is a hollowpoint and the latter is a softpoint. Both have flatnose profiles and expand violently at lever-action rifle velocities. They can be driven a bit faster from my Marlin 1894 than the loads I have included herein, but accuracy suffers.

When filled to the brim with water, the Winchester cases on hand hold 14.2 grains. That’s about 4.0 grains more than the 22 Hornet case will hold and about 3.0 grains less than for the 221 Remington Fireball. The capacity advantage the Bee has over the Hornet allows the use of powders of a slightly slower burn rate. My Sako is quite fond of Lil’Gun and CFE BLK. Reloder 7, IMR-4198, H-4198 and Norma 200 (if you can find it) also work quite well.

My heart has a soft spot for the 218 Bee, mainly because I love old cartridges but also because a Winchester Model 43 218 Bee was one of my first varmint rifles. While its buzz is seldom heard today, the sting is still there.