The 22 BenchRest Remington

Loads for Modern Varmint Bullets

feature By: Charles E. Petty | April, 17

This led Remington to develop BR Basic brass with a small primer pocket that was a 308 Winchester case that could be formed and trimmed to make a variety of wildcats, including 22 or 6mm Remington BRs. The Russian and BR cases spawned a number of wildcats, but the factories took little notice. Sako had a brief flirtation with both PPCs and made some truly accurate, light, varmint-class rifles and factory loads. The wildcats continued to do well in benchrest circles, and there is still debate over “PPC versus BR” that will probably never end.

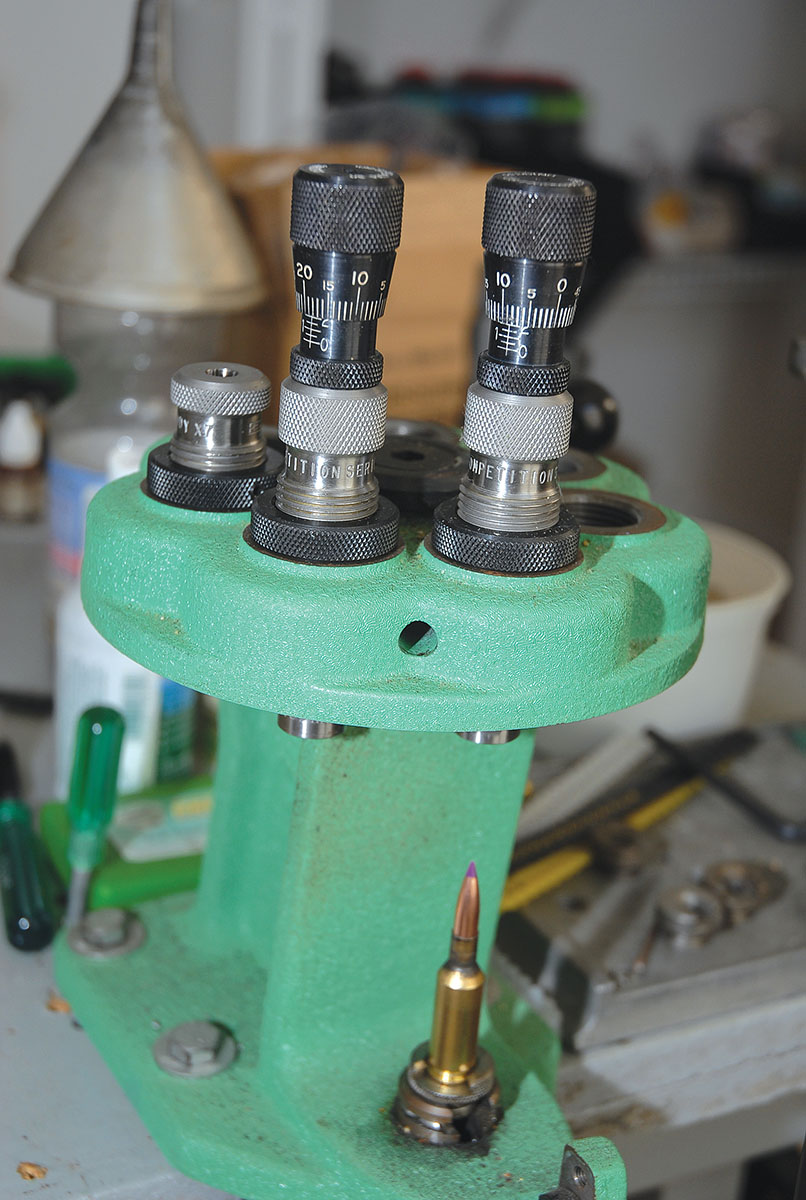

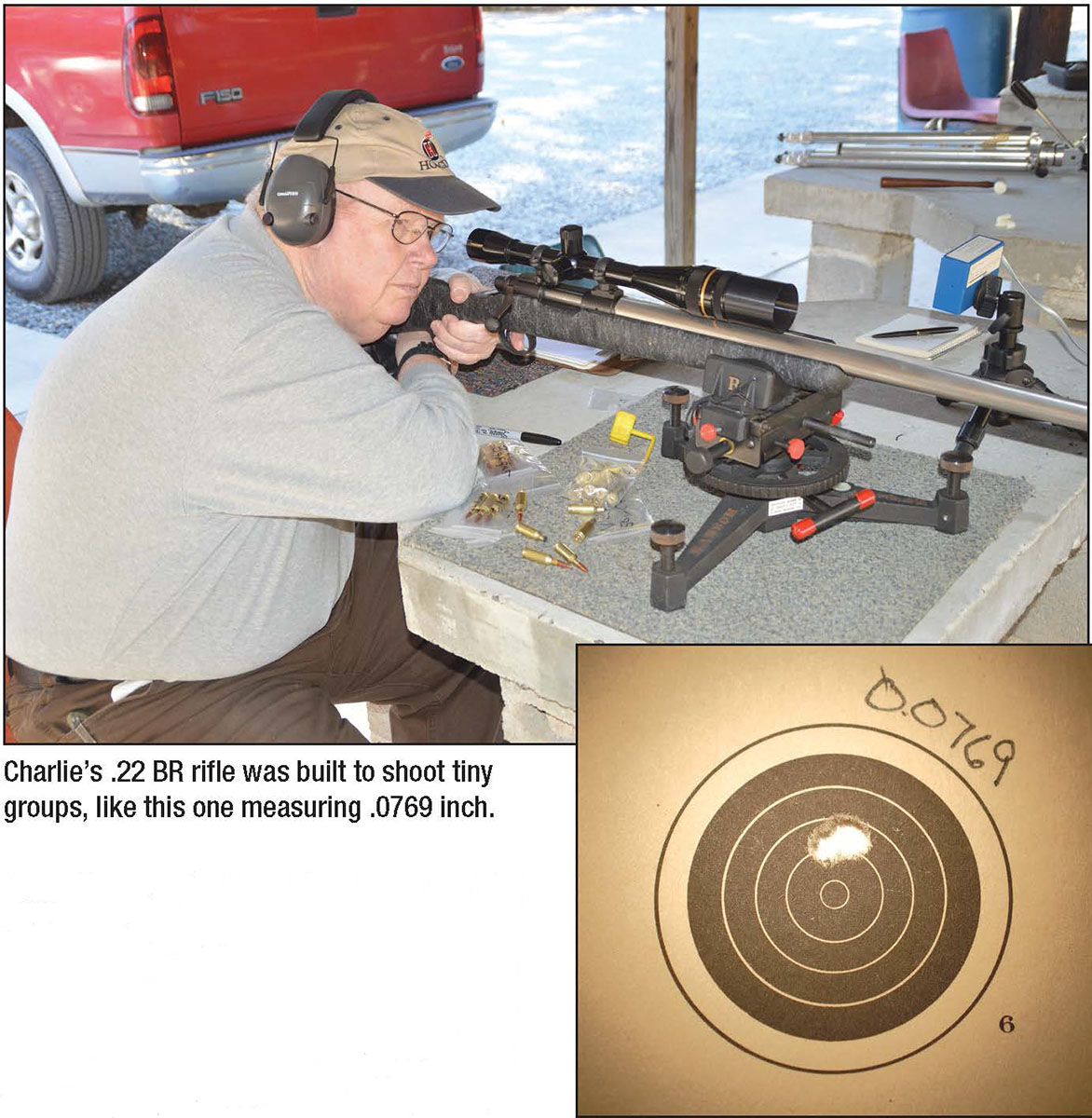

I was gently pushed in that direction and set out to get a 22 BR rifle built. It started with a Remington short action taken off a safe queen. The original Remington stock was free-floated and glass-bedded for a Douglas 24-inch stainless heavy barrel. It was fitted with a 2-ounce trigger. When finished, the rifle weighed 111⁄2 pounds with a Leupold 36x scope and is an absolute joy to shoot. Even though handloads can provide some prodigious velocities, the rifle barely rocks on the rest. Recoil simply isn’t an issue, but just because the cartridge can bust through the 4,000-fps barrier doesn’t mean it is necessary.

I did quite a bit of shooting with it, including more than a few prairie dogs and woodchucks, but interest waned, to be replaced by the 223, and the 22 BR was retired to the safe. Then in 1996, Norma introduced the “new” 6mm Norma BR. With heavier, very low drag bullets, it turned into a very effective long-range varmint round and was quite successful in 1,000-yard benchrest. While the dimensions didn’t change, Norma was re-quired to come up with a different name by the European regulating authority (CIP), but the best news is that 6mm Norma (or Lapua) brass simply needs a trip through a 22 BR sizing die.

This project has involved quite a few trips to the range and more than a few “What is it?” questions. Lots of shooters have never heard of the BR cartridge family, and everyone asked about speed. The 4,000-fps barrier broken by the 220 Swift and 22-250 Remington came up. With the lightest bullets, the 22 BR can do it too, but that is sure to be just as hard on barrels as it is in the other cartridges.

When considering cartridges that are capable of supreme accuracy, overall length can be a major factor. Published data usually shows the length used for the testing, but as loading began I found that some published lengths were so long that the bullet was barely in the neck of the case. Adequate bullet pull is important for uniform powder burning, but sometimes it becomes a balancing act to find the sweet spot. Writers frequently suggest a specific distance for the bullet “off” the lands, and that’s a good place to start; but remember that was with his rifle, and all we know for sure is yours will be different. The only way to really find out is to test with yours. I use Hornady’s gauges for this.

We also need to keep in mind that a change in a component, such as the primer or make of case, can make a difference. The word “match” or “benchrest” on the primer’s label doesn’t guarantee better results, but if the goal is best accuracy, it is still the best place to start. Another possible trap is that just because bullets weigh the same, or look the same, doesn’t mean they will shoot the same. Most handloaders develop some degree of brand loyalty based on previous experience, but it would be virtually impossible to test every possible combination, so experience has to dictate some choices. In this case, some choices were made on the basis of having enough components.

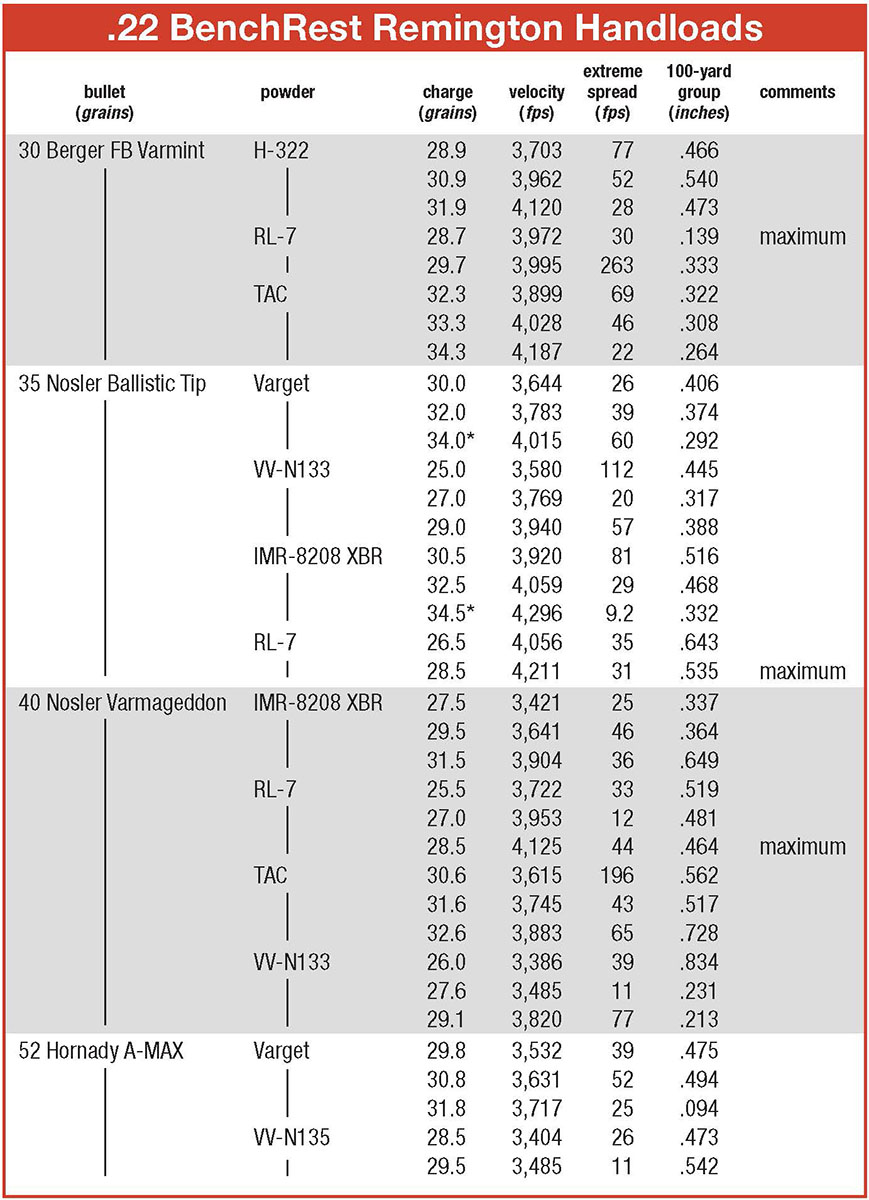

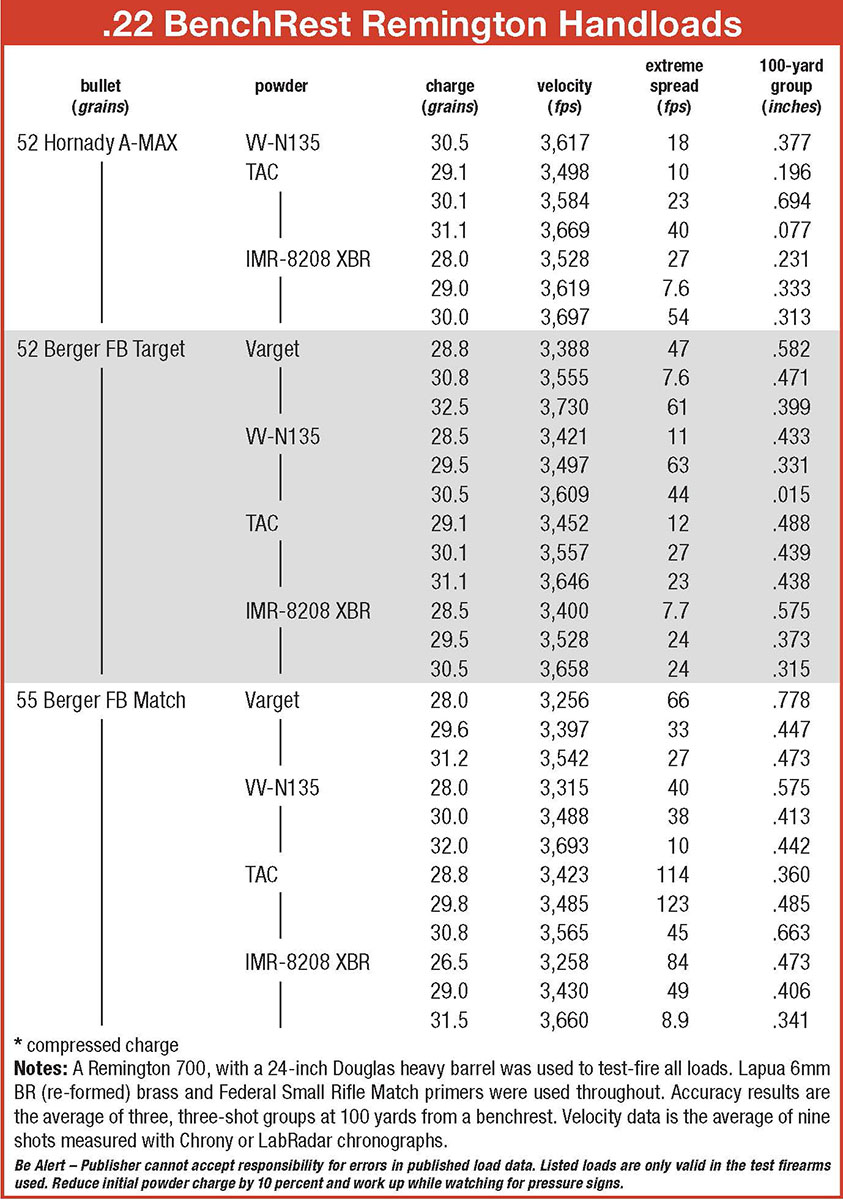

After a thorough search through data sources, a flow sheet was developed for bullet and powder combinations and loading began. It was almost immediately obvious that the chart was too ambitious for the supply of brass. Those were loaded, and off to the range I went.

I have been a big fan of the LabRadar chronograph, but the 22 BR immediately revealed a problem. The LabRadar does not like little bullets. Perhaps this should have been obvious, because most previous testing was done with handguns or larger-caliber rifles, but when the unit just sat there blank, confusion reigned. Going back to the instructions, I found hints that this might have been the case – just wish they had been more emphatic.

Looking back at previous work, the only .22 centerfire used had been a 223 Remington from both an AR and bolt gun, and 62-grain loads had been read properly by the chronograph. The original 22 BR chart started with 30-grain bullets and went up to 55 grains. Chronograph results were mixed with 40s, but 50- and 55-grain bullets were read consistently. Since velocity data is imperative for a project such as this, “Plan B” was needed. My rifle’s 1:14 twist rate eliminated the use of bullets heavier than 55 grains for accuracy, so the focus was on bullets from 30 to 55 grains and the inclusion of some powders that were not around when the BR cartridges peaked.

The 22 Remington BR is a true wildcat, for there is no evidence to suggest that it was loaded commercially. The original 6mm and 22 PPC cartridges have similar case capacities, so with data for those, some scientific mumbo jumbo, fingers crossed and my handy calculator, I came up with some starting loads. From there on it was a matter of working up that required numerous trips to the range . . . and a few false starts. Another source is Wolfe Publishing’s online database, which is a massive compendium of data from a variety of sources (www.loaddata.com).

I hear a lot of talk about “pressure signs,” and primers get a lot of attention. Sadly, primers are a poor indicator of pressure, because by the time they are markedly flattened or cratered, the pressure is almost always above industry standards. One of the best pressure clues, in my experience, is the effort required to lift the bolt handle. Simply dry-fire the action a few times until you have a good idea of the force needed to open the bolt. Then, when you’re shooting, if it takes much more work to open the action, that’s a good indication you found a stopping point.

One early pressure sign that is sometimes ignored is the primer pocket itself. Most handloaders have noticed a case in which it takes less than the usual pressure to seat the primer. The primer pocket is the least supported part of the cartridge case, because there is more brass that can be compressed in firing, and a grossly distorted primer pocket is a big red flag.

Some writers go a bit overboard, saying handloaders should always segregate brass by lot and the number of times reloaded. For loads shot in high volume, like 5.56mm or 9mm, that is too much trouble, because brass is so plentiful. With brass that approaches $1 each, it may be painful to lose one. For this reason I keep BR brass in smaller lots of 20 to 50 that are likely to be fired at the same time.