6mm Remington International

Varmint Loads - and Then Some - for a Storied Cartridge

feature By: R.H. VanDenburg, Jr. | April, 17

Almost immediately, experimenters began to explore the possibilities of the new case. It was, however, a full 20 years before the wildcat 22-250 showed up. In the mid-1930s, in California, then-Capt. Grosvenor Wotkyns and J.B. Sweaney necked the 250-3000 case to accept .22-caliber bullets. Wotkyns promoted the cartridge and contributed some ballistic ideas. Sweaney was the gunsmith and was assigned credit for the cartridge’s development. The early iteration of the Wotkyns-Sweaney 22-250 used barrels with groove diameters of .2225 to .2230 inch.

Farther east, Jerry Gebby of Dayton, Ohio, and J. Bushnell Smith of Middlebury, Vermont, together produced a similar cartridge. Gebby did the gunsmithing and Smith did the load development. Gebby christened the resulting product the 22 Varminter and copyrighted the name. In this case the pair used barrels with .224-inch groove diameters. The Wotkyns-Sweaney version went on to be referred to as the Wotkyns Original Swift, although Winchester, in introducing its 220 Swift in 1935, began with the 6mm Lee Navy case. The Gebby-Smith version is generally recognized as the predecessor to the current factory 22-250 cartridge. Interestingly, it was another 30 years (1965) before Remington formally announced the factory version, now called the 22-250 Remington.

Other experimenters were die-hard benchrest shooters. Harvey Donaldson of Fultonville, New York, was well known in shooting circles. He spent a lifetime shooting woodchucks and crows at long distances in his beloved Hudson Valley. Among the many cartridges he developed was the famed 219 Donaldson Wasp that held nearly all benchrest records for years. Mike Walker, head of design at Remington Arms, was the other. Walker is credited with the development of the 222 Remington that overshadowed the Donaldson cartridge for many years until it, too, was surpassed by the 22 PPC and 6mm PPC cartridges developed by Lou Palmisano and Ferris Pendell.

Walker and Donaldson were experimenting with necking the 250-3000 Savage to 6mm long before the 22-250 became a factory cartridge. Donaldson’s approach was to shorten the case by .25 inch, set the shoulder back and sharpen its angle to 30 degrees. Fireforming would reduce the body taper. This cartridge is referred to as the 6mm Donaldson International. Walker kept the original 250-3000 case length, set the shoulder back but retained the original taper. Shoulder angle was established at 26 degrees. Donaldson specified a one-in-14-inch twist; Walker felt a one-in-12-inch twist was best.

When considering a subject for this issue, a search of my library, including editions of Cartridges of the World, eventually led me to the 6mm Remington International. It had handloading and cartridge history galore and presented an opportunity to work with a fine, old cartridge, even though now largely forgotten. Fortunately, it also solved the problem of what to use for a barrel. I had recently rebarreled a Remington 700 Varmint Special 243 Winchester with a new Krieger barrel in the same cartridge. Since the 250 Savage and 22-250 Remington use the same bolt face as the 243 Winchester, barring some unforeseen circumstance, I had my cartridge.

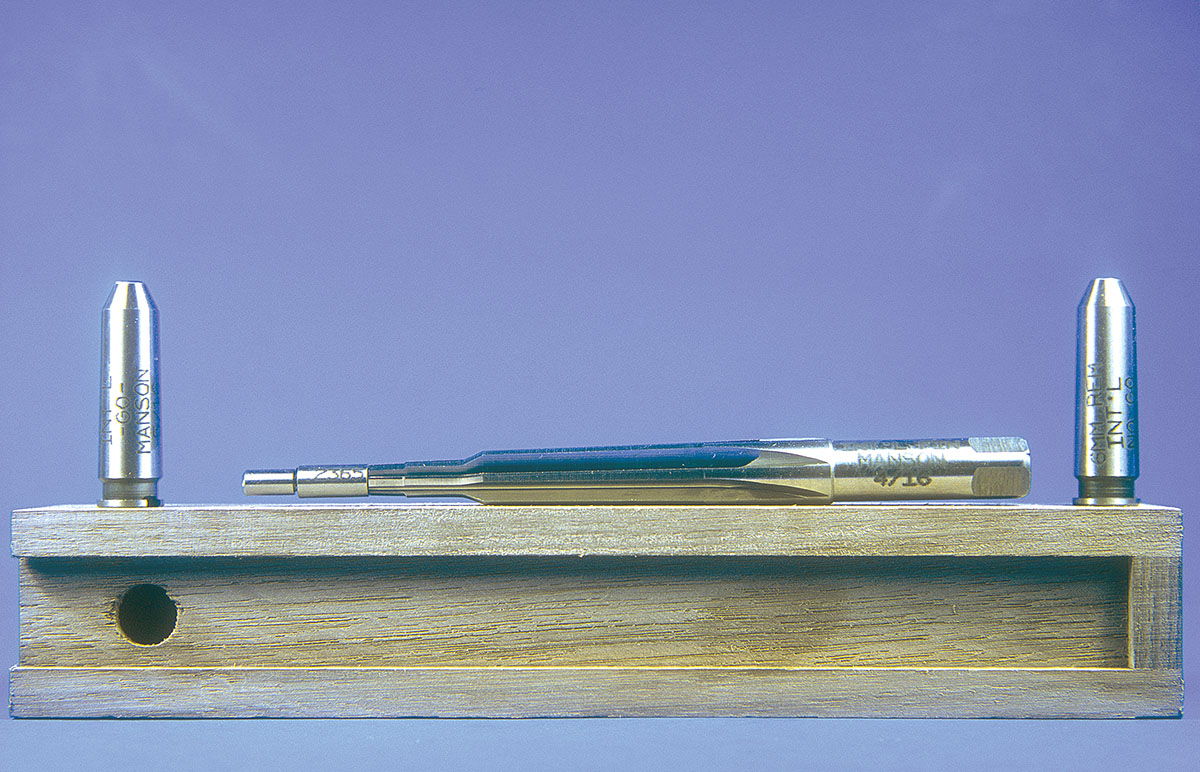

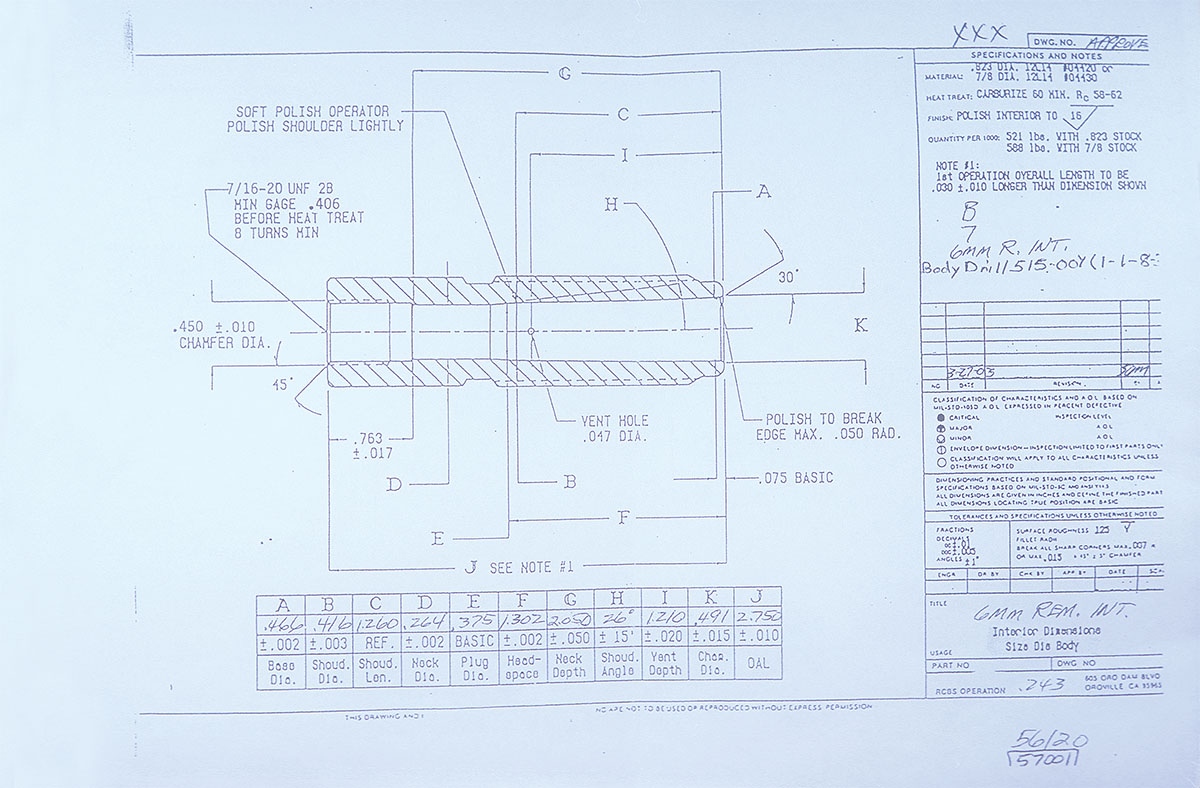

A check with Huntington Die Specialties catalog confirmed that RCBS still makes the dies on special order. In speaking to Kent Sakamoto at RCBS and explaining the project, he provided the die set and forming dies and forwarded a copy of the specification sheets of chamber and die dimensions. From there I went to gunsmith Michael Tulowitski of MJ Tulo Gunmakers (www.mjtgunmakers.com), just outside Denver, Colorado. From him I needed assurance that he could cut back the old barrel, rechamber it for the 6mm Remington International and fit it to the receiver. After the project was concluded, he would swap the old barrel out and reinstall the Krieger barrel. I next approached Dave Manson of Dave Manson Precision Reamers (www.mansonreamers.com) in Grand Blanc, Michigan, and forwarded the cartridge specification sheets to him. In short order I had a chamber reamer and “go” and “no-go” gauges for fitting the barrel to the action. While waiting for the dies, I gathered cases and bullets and selected what I thought would be appropriate powders.

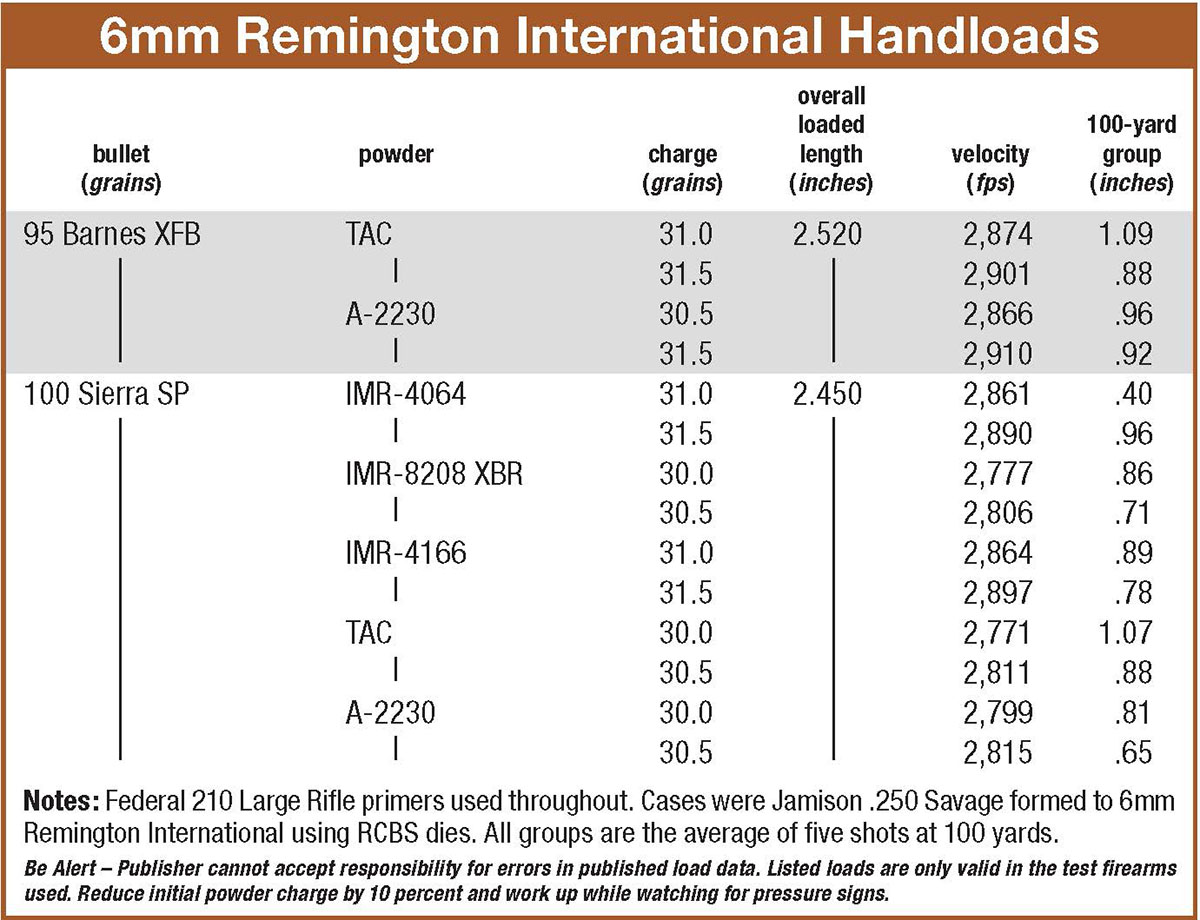

After determining I would prefer to neck 250 Savage cases down rather than neck 22-250 brass up, cases were located at Graf & Sons. Sixty cases of Jamison brass arrived shortly. I had quite a few different 6mm bullets but added more. I ended up with 18 bullets but eventually dropped two, as will be explained. About 16 powders were first considered from a list of 22, from Accurate 2015 to Accurate 4064 in the 2016 Hornady Annual Manual, but the list was further whittled down to 9. To simplify matters a little, the Federal 210 Large Rifle primer was used throughout.

The initial firing was accomplished without mishap, then each fired case was checked to determine if it would accept a bullet. If so, all was well; if not, neck turning or reaming would be required. A fired case that will not accept a bullet is an indication that there is not enough room for the case neck to expand to release the bullet as pressure is building up or, possibly, the case neck is too long for the chamber, thereby pinching the neck onto the bullet. Either instance is a cause for alarm, and the problem needs to be identified and a solution found. In my case, no problem occurred, each case easily accepted a bullet inserted by hand. All cases were then full-length sized and given a final trimming to 1.905 inches.

It seemed logical to begin loading with the powders Walker used, IMR-3031 and IMR-4064, and therein arose the first problem. In spite of beginning with a safe starting load, as I attempted to approach Walker’s maximum loads, the results were a stuck bolt requiring the services of a hefty mallet to open and a primer pocket expanded beyond recognition. While there were several possible explanations, my first effort was to determine if the powders had grown “faster” over the years, as so many have. Ron Reiber, Hodgdon’s chief ballistician, assured me that both powders were still operating under the original 1935 specifications. The first part of the solution came from Handloader No. 121 (May-June 1986), “A New 6mm International Wildcat” by Greg Matthews. In attempting to develop a short-action 6mm cartridge for kangaroo culling that met a series of predetermined criteria, Matthews considered both the Donaldson and Walker 6mm Internationals. He rejected them both, in part because he found neck turning to be a requirement. As noted, I did not, in the case of the Walker version. More importantly, he stated the case capacity of the 6mm Remington International was 43.0 grains. Assuming he was referring to the water capacity, my fireformed Jamison cases held but 41.6 grains.

That difference, plus the selection of primers, with Walker most assuredly using Remingtons and my choice of Federals, plus my 1:10 twist barrel versus Walker’s 1:12 and a difference in bullets, even of the same weight, likely accounted for the difference in pressure. Suffice to say, the problem was solved by cutting Walker’s 3031 maximums by 2.0 grains and his 4064 maximums by 3.0 grains. This gave me a starting point. Diameter of the case web in front of the extractor groove on unfired cases measured .463 inch. Overloads measured .4665 to .4668 inch. My arbitrary maximum was .4655 inch. Since the chamber of my rifle has been recut, another chamber may well have a different dimension, and maximum, even from the same reamer. My approach seems to have worked, with no loss of cases and no difficulty in bolt release throughout load development.

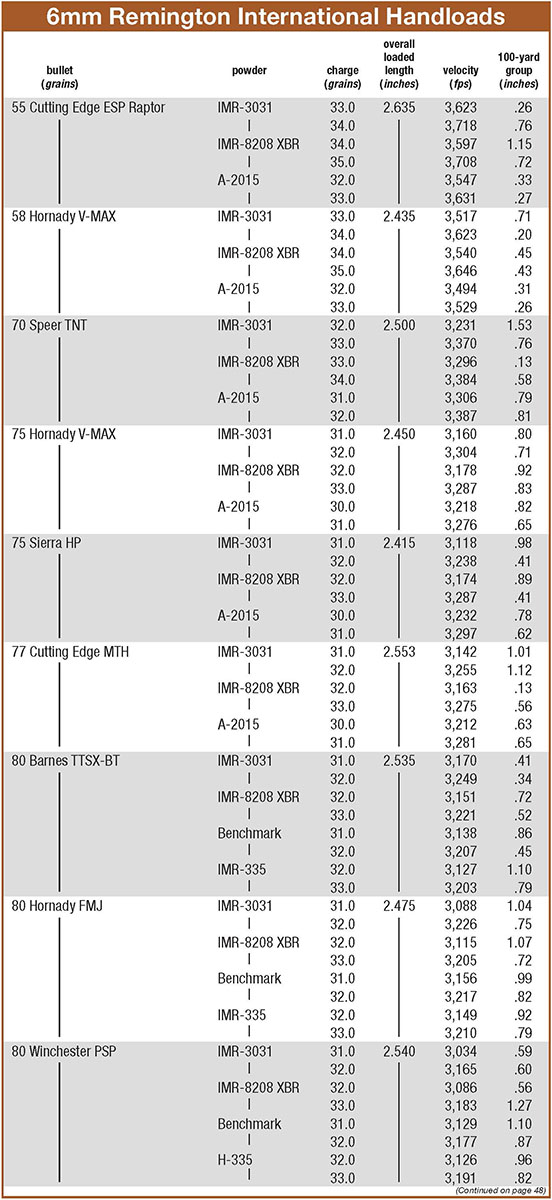

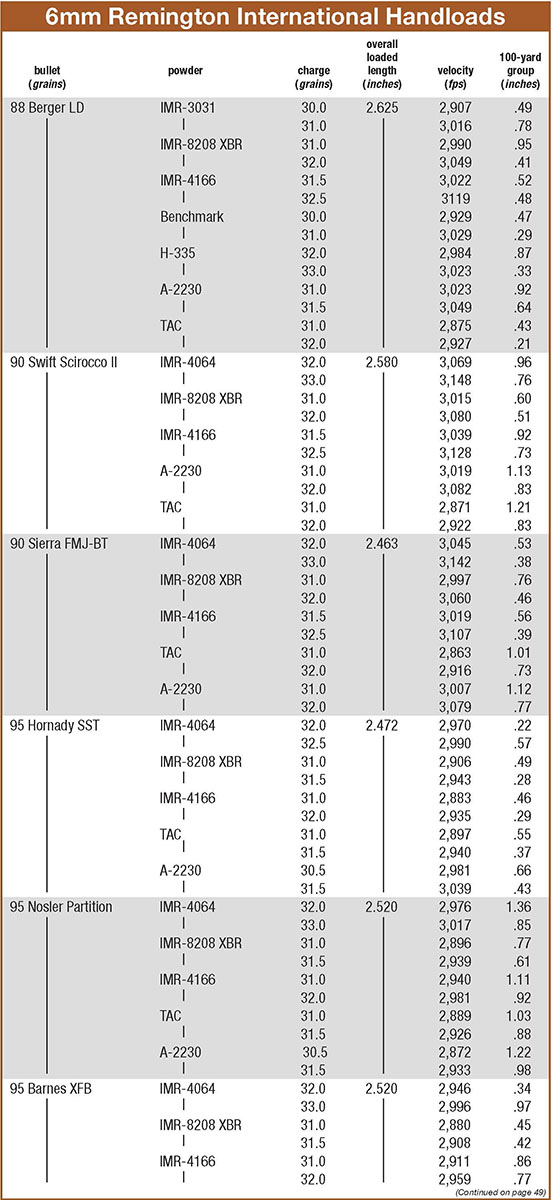

The accompanying load table shows the results. If a reader decides to follow them, cut all loads by 10 percent to start. Make adjustments based on the component mix. While most benchrest shooters prefer the bullet touching the lands, I found seating bullets between .030 and .040 inch off the lands gave the best accuracy. (Interestingly, this was true for the barrel when it was a 243 Winchester.) The table includes some very small groups, perhaps indicative of the cartridge’s potential. There are also larger groups that better reflect some realities. My sighting system topped out at 16x, about half that of modern benchrest scopes; the trigger is a field trigger breaking at four pounds or so. The 1:10 twist is also a detriment for most bullet weights.

In spite of the advances in powders over the years, it was satisfying to note that no powder outperformed the old IMR-3031 and IMR-4064, although some came close. With respect to bullets, my supply of 85-grain bullets ran out and therefore were not included in the results. The best performing bullet was the Berger 88-grain LT; conversely, the Berger 95-grain VLD bullet had to be dropped from the tests as it was too long even for the twist rate, printing in the 2-inch range rather than in the “two’s.” In the end, the bullet should match its application: lighter bullets for most varmint shooting; heavier, and more heavily constructed for heavier game. For pure target shooting, perhaps something in the 85- to 88-grain range would be best.

Finally, I mention David Tubb, 11-time national high-power champion. A few years ago, he came up with the 6XC cartridge (XC meaning across-the-course) for high-power shooting. He used the 22-250 Remington case, modified slightly and coupled with 105- to 115-grain high ballistic coefficient bullets in a 1:7 twist for an excellent, low-recoil cartridge ideally suited to its purpose. In a way, it’s a modern 6mm Remington International.