220 Swift

Handloads for a Versatile Varminter

feature By: Jim Matthews | April, 17

In Winchester’s 2017 catalog, there is a single load listed with a 50-grain bullet at a respectable 3,870 fps. Yet, when Winchester introduced the cartridge in 1935, it was promoted as having a 48-grain bullet thundering out the end of a barrel at a reported 4,110 fps. Remember, however, that when the 220 was introduced, there was still a huge buzz in the shooting community about the 250-3000 Savage (introduced 20 years earlier in 1915) breaking the 3,000-fps barrier. The Swift’s 4,000+ number was jaw-dropping.

Remington’s only 220 Swift load today is a 50-grain bullet at an even more anemic 3,780 fps. Hornady likewise only lists one factory load featuring a 55-grain bullet at 3,680 – the exact same velocity as its 55-grain load listed for the 22-250.

What’s going on here? While the original 4,000+ reading may have been a little optimistic, even today’s reloading manuals show that it’s possible to push a 50-grain bullet nearly 4,000 fps. Most show maximum loads that reach into the 3,850- to 3,950-fps range, and Western Powders still lists one maximum load with Accurate 2700 at 4,035 fps. All these loads are still about 100 to 200 fps faster than what is generated with a 50-grain bullet in the 22-250 Remington at the maximum end of the velocity spectrum.

Let’s go back to the Winchester catalog for a second. For the 22-250, there are seven different loads, and two of those have velocities topping 4,000 fps – both with new lightweight, lead-free bullets. The 35-grain Ballistic Silvertip LF (lead free) is rated at 4,350 fps, and the 38-grain Varmint X Lead Free is 4,090 fps.

If only looking at the Winchester catalog, you probably wouldn’t even consider a 220 Swift, dismissing it as a long-dead, old-time cartridge. If comparing apples to apples, however, the 220 Swift is still the velocity king when it comes to standard .22 centerfire rounds. This is just common sense, if nothing else, because the 220 Swift has the biggest cartridge case of any of the common varmint cartridges in .22 caliber and will hold more powder.

The real versatility of the Swift is that there is no need to load it to its maximum pressure or velocities. Yes, 4,500 fps can be reached with 30- to 35-grain bullets at normal working pressures. However, if long barrel life and long shooting sessions with reduced recoil are important, it is pretty simple to load the Swift down to match 22-250 or 223 performance levels.

Most varmint hunters shooting prairie dogs or ground squirrels will say a shooter begins to notice the recoil of the 220 Swift after about 20 or 30 rounds, and it can become flinch-inducing after 50 or 60 shots. Most shooters have smaller-cartridge rifles for volume shooting, saving the Swift for the long shots.

There’s really no need to swap out for smaller cartridges if a hand-loader is willing to reload for two or three different levels of performance. This same system will also work with other varmint calibers, but it is ideal with the Swift. I use a three-load system with a lot of my rifles, and this is how it works with the Swift:

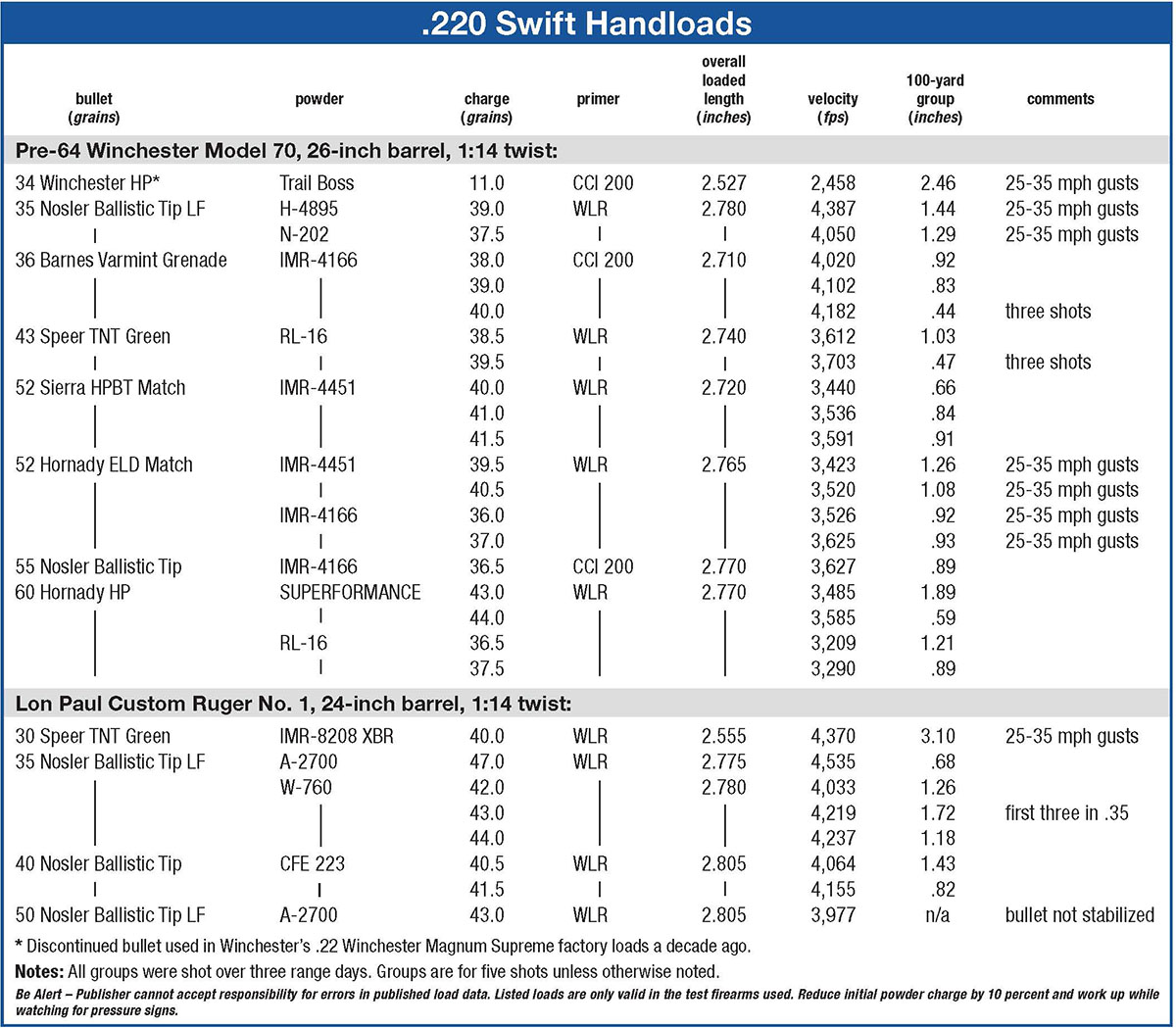

Rimfire Class: In the load table, there is a single 22 rimfire, magnum-class load with Trail Boss powder and apparently discontinued Winchester 34-grain bullets received for another project completed years ago. This type of load will give the 220 Swift shooter ammunition that can be shot all day with almost no recoil, and it takes a lot of shooting to heat up a barrel. There are a bunch of bullets that can be used with these loads, from 30-grain lead-free bullets like the Speer TNT Green or 30-grain James Calhoun slugs up through all the new 35- and 40-grain lead and nonlead bullets on the market. Heavier bullets can be used, but expansion becomes questionable at lower velocities – if that matters. Cast bullet shooters have even more options.

Volume Class: These loads are for volume shooting at midranges – from 100 to 200+ yards – where most shooting takes place on small rodents. Ideal velocities range from 3,200 to 3,600 fps to keep trajectory flat at these ranges. Most times I’m thinking “explosive” performance for these loads and will use from 35-grain nonlead bullets up to 53-grain lead-core bullets. There are dozens of options in this weight range – just about any .224-inch bullet can be used. In the accompanying table, a number of these midrange loads are listed. The benefit of these loads is that they have very modest recoil and don’t heat up the Swift’s barrel. You also get long case life when reloading to these levels.

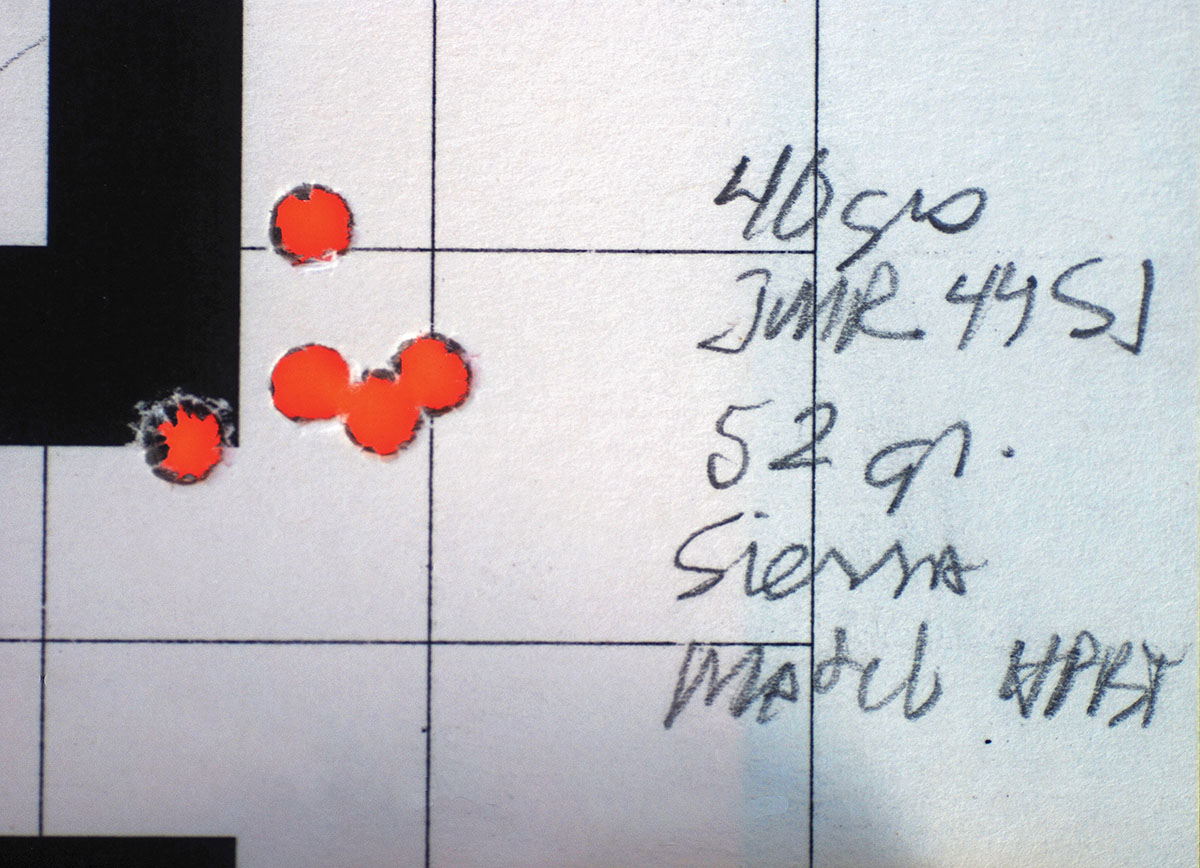

Long-Range Class: These are go-to loads when the critters get wised up and only pop up at long range, from 250 to 400 yards or more. This is where aerodynamic bullets and top-end velocities are used to reduce bullet drop and wind drift. Because of the 1:14 twist rates in the two rifles I was shooting, bullet choices were limited. If you have a Swift with a 1:12 rate (or even a 1:10 or faster twist), a wide selection of excellent target/varmint bullets are available. Top velocities in the 3,600- to 3,900-fps range with 52-grain or heavier bullets are used.

While I didn’t say anything about a fourth class, I’d keep my loads at maximum velocity using the lightest bullets when hunting coyotes; the new nonlead slugs shine here. The 220 Swift loaded with these 30- and 35-grain bullets at 4,500 fps or so will result in little pelt damage. They are also very flat shooting out to all practical shooting distances. This is not volume shooting, so there is no need to worry about recoil or hot barrels.

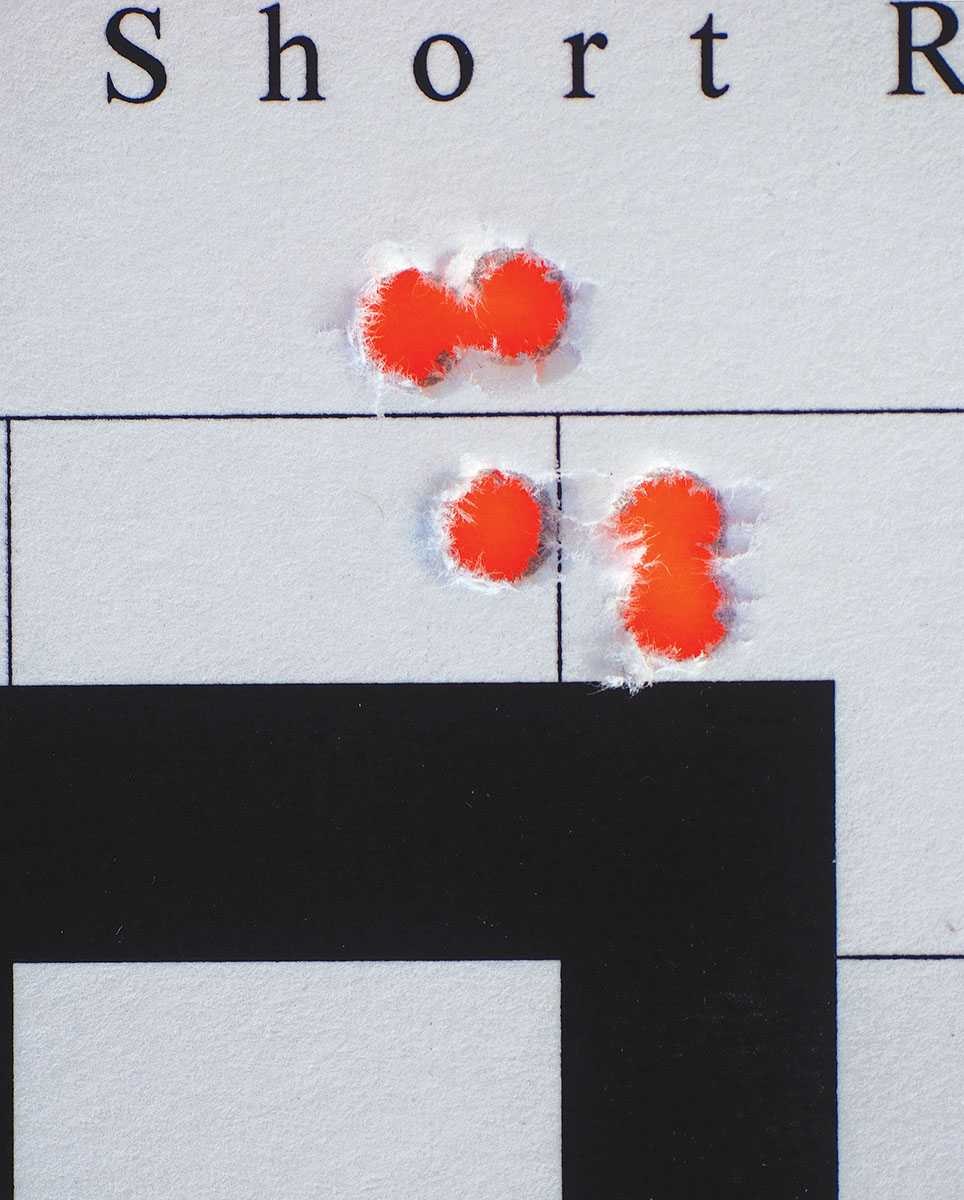

You can see in the load table that these recipes are focused on new powders and/or new bullets, mostly the new nonlead slugs. Where I live in California, we will soon be forced to shoot nonlead for all varmint hunting statewide, and that plague of political nonsense is spreading to other states and federal lands. That’s the bad news. The good news is that the new nonlead bullets are proving to be accurate and deadly. I’ve been relieved to find the Nosler 35-, Barnes 36- and Speer 43-grain bullets – all the nonlead bullets I’ve tested so far – have proved extremely accurate in both of the Swift rifles used here, and their field performance is excellent.

If there is a legitimate bonk on the 220 Swift, it is simply that most of the older rifles available usually have 1:14 twist rates. Both the pre-64 Model 70 and the custom Ruger No. 1 used for this article had that slow twist rate, and they would not stabilize some of the new, longer, nonlead bullets or the heavyweight target bullets. The Nosler 50-grain Ballistic Tip LF is a long bullet, and I figured that at 3,900 fps or so it would provide an ideal long-range load. There was one problem: It shot patterns – not groups – with the bullets keyholing through the target at 100 yards from both test rifles.

The 220 Swift has always been a bit of an oddball. The semirimmed case doesn’t fit any popular molds, although the rim size is the same as the 308/30-06 family of cartridges, allowing the same bolts to be used. Its neck angle, a gentle 21 degrees, and sloping body taper are widely ridiculed, but Swift shooters have found the cases don’t stretch any more than other “superior” varmint rounds. It’s just fast, and it shoots well – maybe even better than it should.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the Swift – other than its velocity – is that the cartridge was introduced in 1935 before there were affordable, high-power riflescopes on the market. It was difficult to take advantage of the Swift’s accuracy. Most shooters of that era still used iron sights until well after World War II, and it wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that high-power optics became generally available and affordable. That was the heyday for the 220 Swift, proving the cartridge was at least a couple of decades ahead of its time.

Sadly, few major gunmakers are chambering rifles for the 220 Swift today. The only current Swift listed in catalogs is the Remington Model 700 Varmint SF, while Winchester, Ruger and Savage are no longer offering rifles so chambered. The introduction of the 22-250 in 1965 seemed to be the final nail in the Swift’s popularity coffin until a Ruger-inspired revival of the cartridge in the 1970s and 1980s fueled a new flurry of interest. Sales of Ruger M77 and No. 1 220 Swift rifles were so brisk that Remington, Winchester and Savage started making rifles. That revival continued into this century before the cartridge fell out of favor again. That means there are a lot of Swifts in the used-gun marketplace.

The accompanying loading data for the 220 Swift mostly features the new lead-free bullets and/or the latest batch of temperature-stabilized powders and those that reduce copper-fouling. Data for the new powders is very limited, because manufacturers focus their load development on the most popular rounds. The loads here give Swift owners some starting points for these new components. The new Reloder 16 powder was particularly impressive in delivering low extreme velocity spreads (usually less than 30 fps), but IMR-4166 was in the same ballpark.