22 Super Jet

Loads for an Old WIldcat

feature By: Jim Matthews | October, 19

Most factory chamberings actually began life in this way, and sometimes the wildcats gain more fame than their parent cases – think of all the wildcats on the 284 Winchester case or the 22-250. Beyond these two schools of thought, however, the “need” for a wildcat can become a bit more esoteric.

Friend Paul Neidermann is a consummate tinkerer, inventor, gunsmith, stockmaker and ground squirrel shooter. He is also a fan of single-shot Martini Cadet actions for their compactness and simplicity. When he decided to build up a varmint rifle just for his regular trips to a large California ranch to shoot ground squirrels, the small Martini single shot was to be the heart of the rifle.

Next came caliber/cartridge choices. The first concern was that they must be short enough to get around “the corner” to chamber in the small, falling-block Martini action with its curved loading ramp. That limited cartridges to around 2 inches long for easy feeding and extraction. He considered factory chambers: The

Neidermann took a .22-caliber barrel that a friend had given him with the throat shot out. He cut off the old chamber and warn part of the barrel, rechambered it to 22 Super Jet and fit it to the action. It ended up being 22 inches long. Neidermann also did a little action work by removing a little metal from the right side of the action adjacent to the loading ramp to make reaching brass easier for loading and unloading.

The action was sent off to engraver Barry Lee Hands, who did a simple but beautiful bold scroll on both sides of the action. The receiver was color case hardened and a gold inlaid kangaroo graces the top of the receiver (unfortunately mostly hidden by the scope). Neidermann then used a lovely piece of highly-figured walnut and made a slim forearm and buttstock that left the rifle trim, handy and striking. The rifle was finished off with a Leupold VXII 3-9x scope and weighed just a snick over 7 pounds. Completed in 2003, it has been beat around on ranch roads and carried through a lot of oak woodlands, fulfilling its intended function.

All this made me think about wildcats and shooters in general. We are a unique breed that seems to attract people who are prone to constant and endless tinkering, shooters who are never satisfied with what they can buy off the shelf. You don’t see many (any?) recreational baseball or tennis players designing and making their own custom bats or raquets. Shooters are different. I started handloading as a teenager back when we needed to reload to get the best game bullets and make the most accurate ammunition. I had my first wildcat cartridge before I was 30. This is not unique; it has been that way throughout shooting history. Most of the major developments that eventually became factory standard started in garages and small shops.

I tried to explain this to a non-hunting, non-shooting friend recently. I had just started working with Neidermann’s 22 Super Jet at the time and tried to detail the steps in the process just to form brass to load ammunition. Thanks to the old movie “Dirty Harry,” my friend knew about something called the 357 Magnum. In its day, it was the whizz-bang: The most powerful handgun cartridge ever made. He knew that. So I explained that the Super Jet was made from 357 cases. He had no idea about the size of the ammunition. “Think of something about the size of a woman’s pinky finger from the second knuckle to end of the finger,” I told him.

I explained that the 357 is a rimmed case with roughly parallel sides, but the first step of making the Super Jet was to progressively squeeze down about the first .25 inch of that case neck down from .35 inch to .22 inch so it had sharp shoulders. This is done in steps with three dies that squeeze down the brass gradually. If you try to do it all at once, you mash the thin neck and ruin the brass. This process has to be done in three steps.

Then trim the end of the case to make it square and get it to the correct length to match the Super Jet chamber, and run it through the final full-length sizing die. You can then proceed to load the brass and shoot it in the specially-chambered rifle. He followed that pretty well, but wondered why anyone would go to all that trouble. “Can’t you just buy ammunition at the store and shoot it?” he asked. Non-shooters just don’t get it. Handloaders start nodding their heads and imagining other applications where a Super Jet would be ideal. Maybe they have a one of those neat Ruger 77/357 bolt-action rifles or some other bottom-fed 357 Magnum. It would be a simple matter to rebarrel to the 22 Super Jet.

Three tidbits of advice if you use form dies: First, don’t use once-fired 357 Magnum brass; only use new brass. The once-fired bass always split on the first firing in my testing unless I annealed them before sizing. New brass doesn’t require annealing and I did not have any split cases. Second, the first step-down die requires that you sort of “feel” the case into the mouth of the die at the beginning of that first sizing operation. If neglected, you can mash the mouth of the case. Third, don’t try to skip step-down stages. Doing so leads to damaged cases. I know this because I had to pitch several pieces Starline brass I mashed while making my own Super Jet brass.

The RCBS form die set includes three dies (and an extended shell holder) that take the outside diameter of 357 cases from .373 inch to .318, .292 and .245 inch. The full-length die in the regular die set does the final sizing. I trimmed all the cases to 1.285 inches and deburred the inside and outside of the necks before reloading. My brass was nearly identical to the custom brass.

Neidermann’s Martini Super Jet has a very long throat, so bullets could never be seated out far enough to even come close to engaging the rifling. Even with significant bullet jump, the rifle still shot very well, with groups running from 1.5 inches down to .7 inch or smaller.

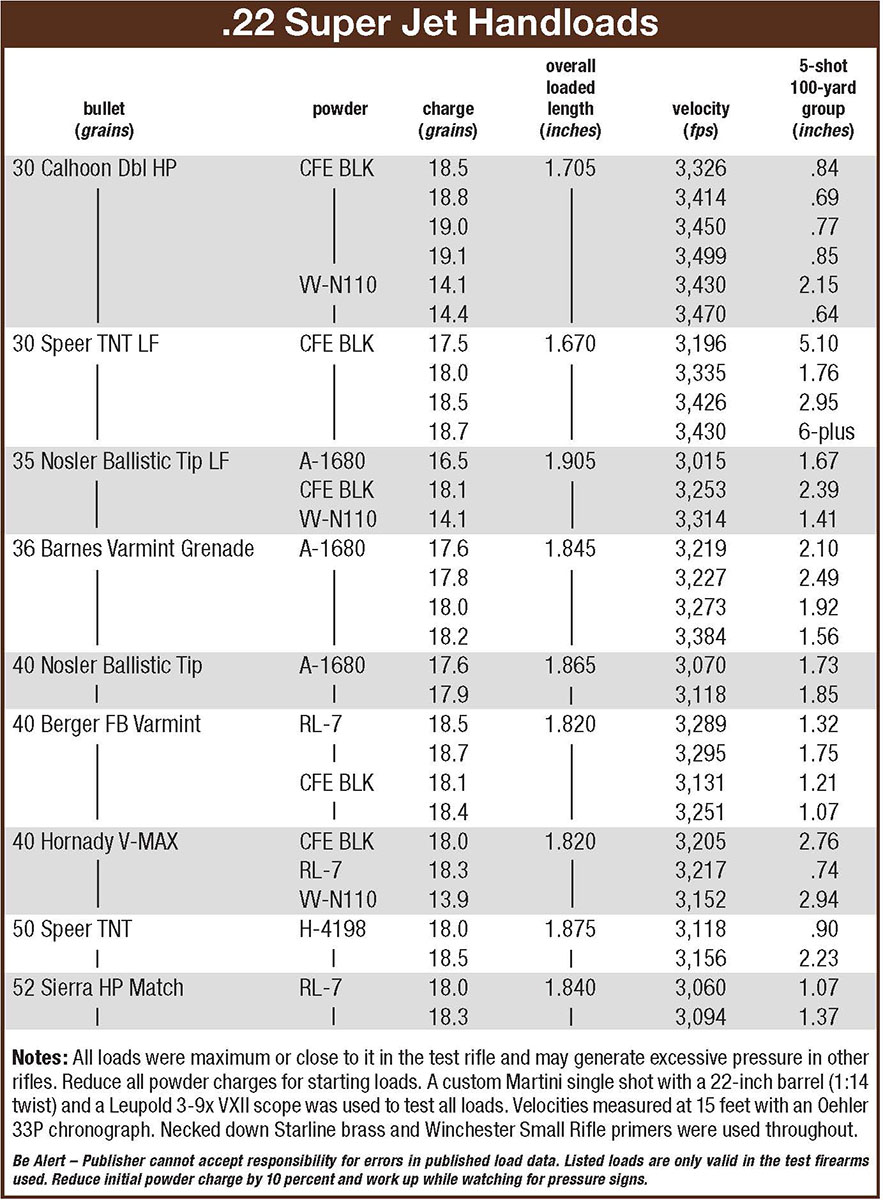

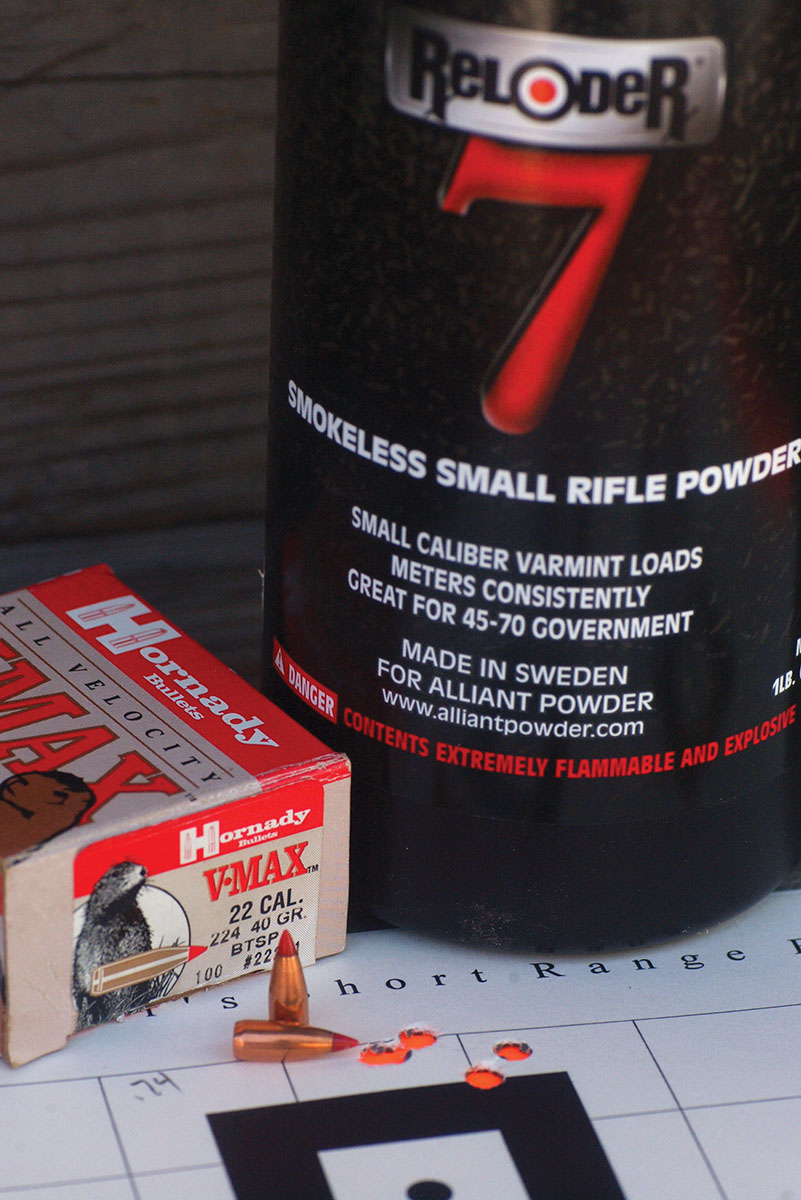

I was anxious to try CFE BLK in the Super Jet. This powder has become a go-to powder in my 19 Calhoon Hornet because of its reported clean-burning qualities and consistency. Also included were Vihtavuori N110, Accurate 1680, Reloder 7 and H-4198. I stuck with bullets on the light end of the .22-caliber spectrum, not going above the 52-grain Sierra hollowpoint match bullet because the rifle barrel had a 1:14 twist rate. The other lead-based bullets tested included the Speer 50-grain TNT hollowpoint, the Hornady 40-grain V-MAX, the Berger 40-grain FB Varmint, Nosler 40-grain Ballistic Tip and the Calhoon 30-grain Double HollowPoint. Three non-lead bullets included the Speer 30-grain TNT, Nosler 35-grain Ballistic Tip and the Barnes 36-grain Varmint Grenade.

All loads in the Neiderman rifle presented no problems with extraction, function or other pressure signs. However, I caution anyone who builds up a 22 Super Jet to approach my top loads with extreme caution. Use the starting charges and work up carefully while watching for pressure signs. Differences in throats, brass and chamber dimensions can have dramatic impact in pressure in small cases like this one.

Having worked with wildcats in the past, I shot what I call “ladder loads” because I had no pressure-tested factory load data available (and even limited “Internet” loads) for two of the powders. For the ladder, I start with very low loads, working up one load at the time in .2-grain increments. I measured case heads, measured velocities and watched for other pressure signs while shooting the loads in the ladder.

Ironically, the best group, measuring .45 inch, was shot with VV-N110 and the Hornady 40-grain bullet. The ladder loads used 13.0, 13.2, 13.4, 13.6, and 13.8 grains of powder, and velocities ranged from 3,009 up to 3,147 fps. I later loaded five more with the 13.8-grain load and shot them on a howling wind day for a 2.94-inch group, with four in 1.09. The average velocity for the five was 3,152 and extreme velocity spread was just 26 fps.

Vihtavuori N110 had the lowest extreme spreads of any of the powders tested, with most loads showing five-shot spreads of less than 35 fps, and some in the low 20s. Even with higher extreme spreads, CFE BLK produced as many good groups. However, as seen in the load table, there were good groups shot with all powders tested.

When reluctantly returning the rifle to Neidermann, he was just starting work on another Martini for a friend. When our discussion turned to what was going to be the chambering, Neidermann said they had talked about a Super Jet since a reamer and form dies were already in hand. I suggested they might want to look at using the 357 Maximum case, which would have about 30 percent more case capacity, or about the same as the 222 Remington in a shorter, rimmed package. Neidermann scrounged around in the shop and found a piece of 357 Maximum brass. It was too long to make the turn on the angled loading ramp in the little Martini – but maybe after it was sized down to 22. Or, if need be, it could be trimmed some. I could see Neidermann’s brain was working.