The 221 Fireball

A Hot Little Cartridge

feature By: Layne Simpson | October, 25

During the 1950s, a fellow by the name of Jim Harvey, who specialized in designing firearms, cartridges and fishing lures, decided to convert the Smith & Wesson K22 revolver. He

converted it to handle the slightly shortened 22 Hornet case. Jim thought it would be great fun to play with and sell a few guns as well. Velocity was a bit lower than expected, so Harvey fire-formed the shortened Hornet case for an increase in powder capacity and called it the 224 Kay-Chuck. It could also be accurately described as a shorter version of Ackley’s 22 Hornet Improved. The fairly large number of Smith & Wesson revolvers converted by Jim Harvey and converted for him by Bennett Gun Works of Delmar, New York, is an indicator of the popularity of his 224 Kay-Chuck.

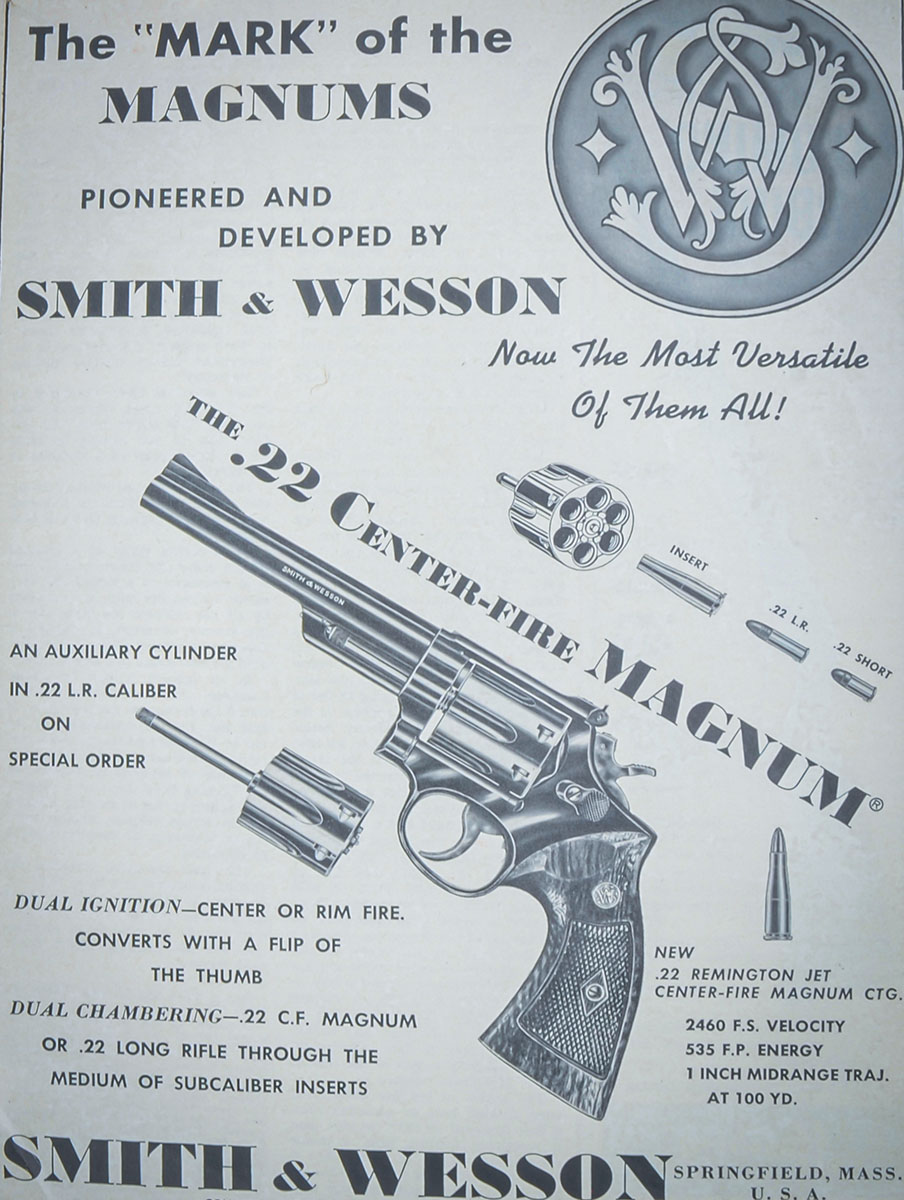

More than one time through the decades, a big guy has stepped in and stolen the thunder from a little guy, and it happened to Jim Harvey when Smith & Wesson charged Remington with developing a high-velocity .22-caliber centerfire cartridge for a double-action revolver. Formed by necking down the 357 Magnum case for a .222-inch jacketed bullet weighing 40 grains, the 22 Center-Fire Magnum, as Smith & Wesson called it, or 22 Remington Jet, as Remington called it, was introduced in the Smith & Wesson Model 53 revolver in 1961. Barrel length options were 4 inches, 6 inches and 8 3⁄8” inches. The barrels were given a .222-inch groove diameter because decision-makers at S&W decided to increase the versatility of the Model 53 by including six chamber inserts reamed for the 22 Long Rifle. A few dollars more bought an extra cylinder that held six 22 Long Rifle cartridges. The Model 53 with a 6-inch barrel, which I enjoyed shooting for several years, had the extra cylinder in addition to the six-chamber inserts. The box of Hornady .222-inch, 40-grain bullets I still have reads “22 Cal Jet,” and the $6 gun store price tag indicates how long they have been with me.

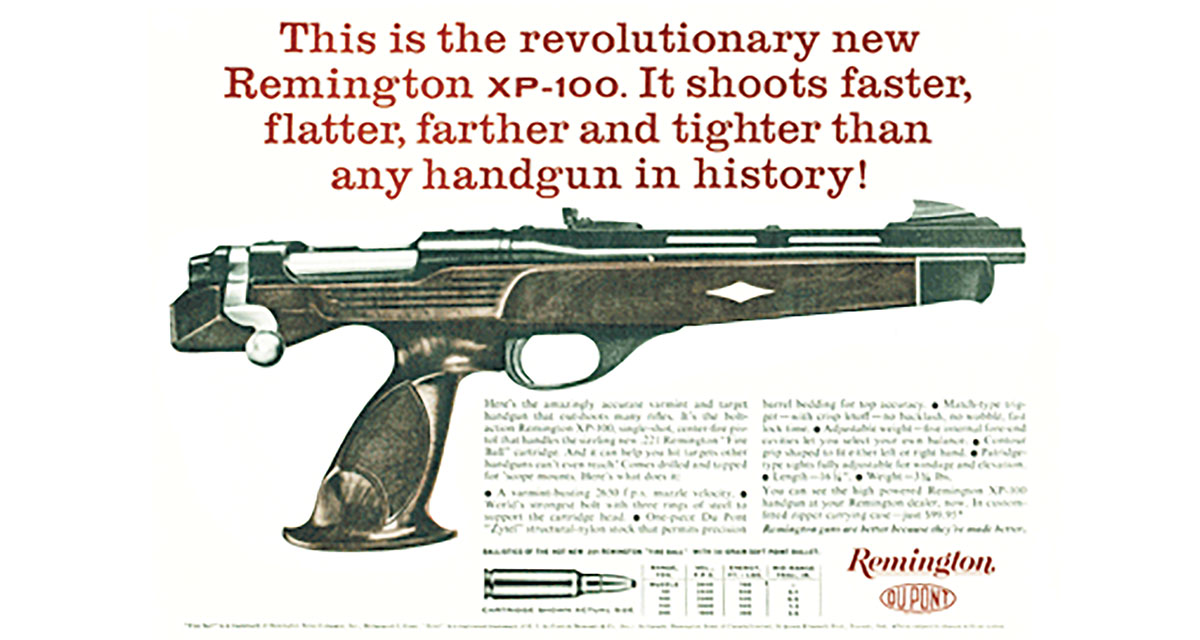

I devoted a bit of space to the 22 Jet because Remington engineer Wayne Leek, who was in charge of designing it for Smith & Wesson, decided that if fast was a good idea, even more speed combined with better accuracy from a handgun would be an even better idea. So, he took a hard look at the action of the Remington Model 700 and headed for the drawing board. Several versions of an Experimental Pistol (XP for short) were built. The action Leek ended up with was about an inch shorter than the short Model 700 action. Positioning the grip at the rear of the stock made for an unbalanced handgun, one rather cumbersome in the field. Moving the grip toward the front of the action felt good in the hands, but it put the finger lever some distance from the trigger. That was solved by connecting the lever and the trigger with a long piece of steel called the transfer bar. A two-position safety lever was located just behind the dog-leg bolt handle. The bolt handle was given that shape because a straight handle would hit the back of the shooter’s hand during recoil. The stock was made of DuPont Zytel, which first appeared on the Remington Nylon 66 rifle in 22 Long Rifle introduced in 1959. Two halves were formed in moulds and then fused together. The balance of Wayne Leek’s handgun could be changed by placing .38-caliber jacketed bullets into cavities in the barrel channel of the stock.

Barrels of various weights and lengths were tried, but to keep the handgun compact for field carry, 10.5 inches was decided on. Heavy barrels drove more tacks, but they caused the gun to exceed the ready-to-go weight goal of five pounds, so the barrel ended up being quite thin. In those days, all guns departed the factory with open sights so as to give them something to attach to and to draw attention away from the skinny barrel, a ventilated rib made of structural nylon. A front sight in the shape of the fin of a shark made the gun appear to be moving fast, even while it was sitting still.

At the time, the 222 Remington was extremely popular among varmint shooters and benchrest competitors, but it proved to be too much of a good thing in a 10.5-inch handgun barrel. That case was gradually shortened, and while 1.400 inches seemed to be the magic number, there was still considerable muzzle flash, so 221 Fireball remained appropriate for the name of the new cartridge. The name alone likely sold a lot of guns. Maximum chamber pressure for the 222 Remington was 50,000 pounds per square inch (psi), and increasing it to 52,000 psi for the 221 Fireball probably improved propellant burn efficiency a bit. The advertised muzzle velocity of the 50-grain bullet was 2,650 feet per second (fps) versus 2,100 fps for the 40-grain bullet of the 22 Jet.

The XP-100 handgun, as it was eventually called, was introduced in 1963, and it came in a nice padded case. The price was $99.95, and a 20-round box of Remington ammunition loaded with a 50-grain bullet at 2,650 fps added $3.00 to the tab. Remington’s introductory advertisements said it all: “This is the revolutionary new Remington XP-100. It shoots faster, flatter, further, and tighter than any handgun in history.” My Wyoming friend, Les Bowman, had many friends at Remington, and he received one of the first built. His article on the new XP-100 appeared in the 1964 Gun Digest. As a historical note of possible interest, the action of the Model 600 carbine introduced by Remington in 1964 was a repeating version of the XP-100 action. Like the handgun, its barrel also had a nylon ventilated rib replete with a shark fin front sight. The Model 600 also sold for $99.95. While the handgun and the carbine were being designed at the same time, the handgun was introduced first to avoid possible issues of legality with the U.S. Government.

While writing this, I decided to see how the capacity of the 221 Fireball case compares with the 22 Hornet and

218 Bee cases by weighing them and weighing them again after they were filled to the brim with water. The Hornet and Bee cases were made by Hornady, and the Fireball cases by Remington. At 22.3 grains, the 221 Fireball was the clear winner, and while the 218 Bee does not seem far behind at 18.6 grains, it represents a 20 percent difference in capacity. The Fireball is also loaded to higher pressures. Arriving at a distant last in capacity was the 22 Hornet at 14.3 grains. The Bee is often thought of as a cartridge for lever-action rifles, and while that’s where it began, it was once available in the Winchester Model 43 and the Finnish-built Sako L46, both having turn-bolt actions. My Sako immigrated to America around 1952, and it is quite accurate. Unfortunately, Bee cases have become difficult to find, while 221 Fireball cases made by Nosler are readily available. In a pinch, form dies available from Redding will create 221 Fireball cases from 223 Remington brass. As I write this, Nosler is the most reliable source of 221 Fireball ammunition, with Remington and HSM tied for a very distant second place in availability.

The original XP-100 is great fun to shoot at distances within the effective range of the 221 Fireball from its short barrel. Far more accurate and pushing a 40-grain bullet an honest 600 fps faster from its fairly heavy 24-inch barrel was a Cooper Model 21 Montana Varminter that I should have kept. One of the most useful rifles in my battery is on a short Remington 700 action blueprinted by Kenny Jarrett. It has been with me for many years. Interchangeable bolts and barrels enable me to test a number of cartridges, including the 221 Firball, 223 Remington, 22-250, 220 Swift, 6.5-284, 6.5 Creedmoor and 308 Winchester. While shooting at the range or in the varmint fields, I use a compact action wrench and barrel vise made by Davidson Manufacturing to switch barrels in about two minutes. The stock is by McMillan.

I am aware of only two rifles produced by Remington in 221 Fireball. Each year from 1980 until 2005, the company built a limited number of Model 700 Classic rifles with blued barreled actions and walnut stocks. The series began with the 6mm Remington and ended with the 308 Winchester. The 221 Fireball came and went in 2002. The other rifle was the Model 700 CDL SF with a walnut stock and stainless-steel barreled action with a 24-inch fluted barrel. I actually have two, one in 221 Fireball, the other in 17 Fireball, and I believe both were built in 2017.

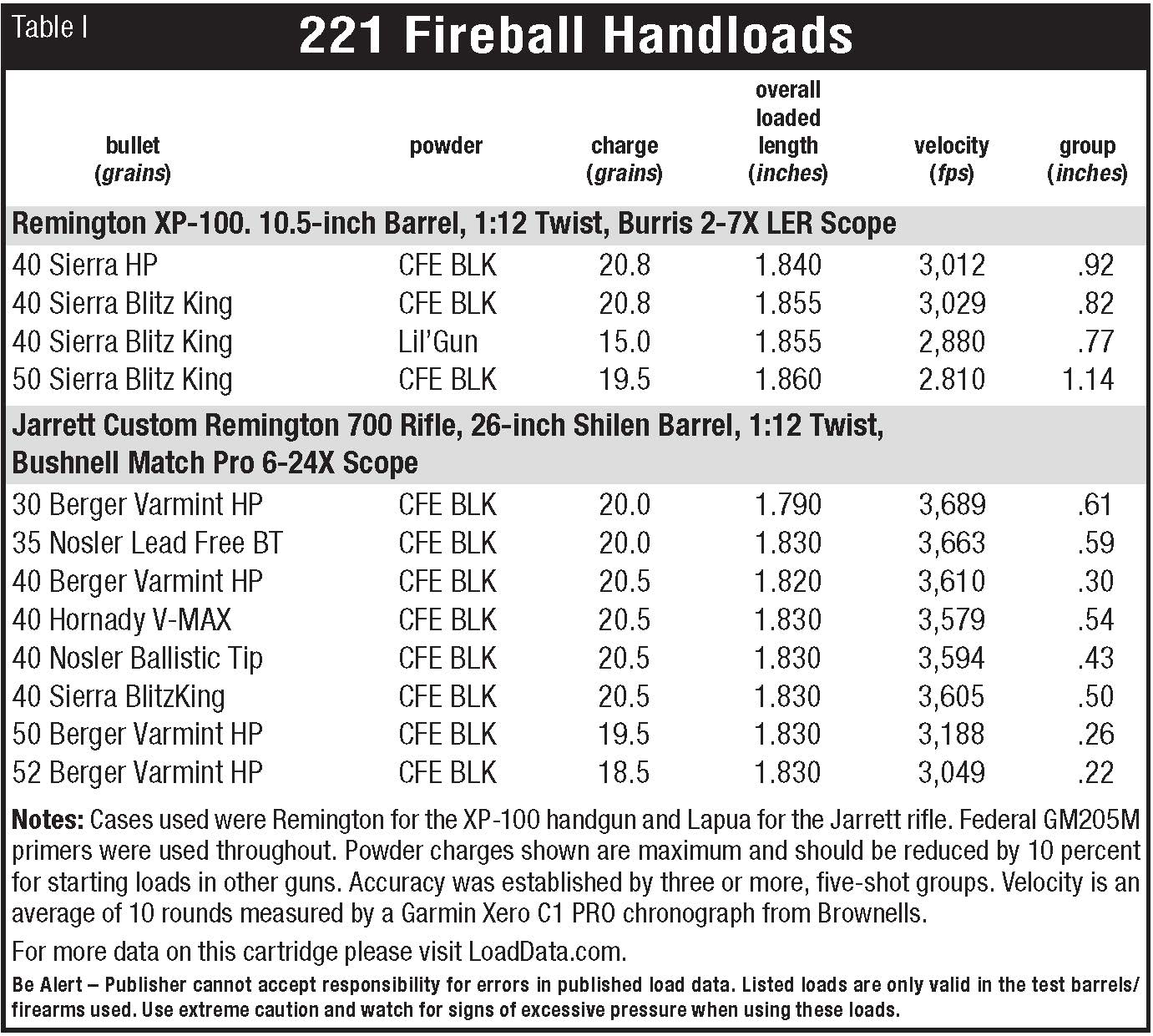

Like the 22 Hornet, 221 Fireball handloads can produce extremely high velocity spreads. This can usually be reduced in both cartridges by using a Redding Type S full-length or neck-sizing die, which takes interchangeable neck sizing bushings available with various interior diameters. I actually have

both. As a rule, the bushing should be .001 to .002 inch smaller than the case neck diameter with a bullet seated. For the 221 Fireball, I use a bushing .004 inch smaller than the neck of a loaded round. For example, the neck diameter of the ammunition I am now shooting is .247 inch, so when sizing those cases, I use a .243-inch bushing.

If I could have only one powder sitting on the shelf for loading in the 221 Fireball, it would be CFE BLK. It does a great job of minimizing jacket fouling in an active prairie dog town, and accuracy leaves nothing to be desired when loaded behind accurate bullets and fired in an accurate rifle. Equally important to the varmint hunter who shoots hundreds of rounds each year, it flows through a good powder measure with little to no charge-to-charge weight variation. As a bonus, Hodgdon classifies CFE BLK as a temperature-stable propellant. There are others. A serious squirrel-shooting pal who hoards Nosler 40-grain Ballistic Tip factory seconds for his three rifles in 221 Fireball, swears by Vihtavuori N120. Like most of the rifle powders made by Vihtavuori today, it contains what the company describes as a decoppering agent. It also ignores wide swings in ambient temperature. Like other dwarf rifle cartridges, small increases in powder charge weight produce big increases in chamber pressure in the 221 Fireball. For this reason, beginning with a pressure-tested starting charge weight recommended by a reliable source and carefully working up in half-grain increments is extremely important.

While the XP-100 was designed for bumping off distant varmints, it has occasionally seen action in other places. When I began competing in handgun metallic silhouette years ago, several of the guys shot the XP-100 with the 221 Fireball loaded to primer-flattening pressure with the Speer 70-grain bullet. It usually delivered all the push needed to reliably topple steel chickens, pigs and turkeys; fringe hits often failed to push over 60-pound rams.