17-222

Resurrecting a Wildcat

feature By: Art Merrill | October, 20

Some folks just like the challenge of resurrecting a long gone varmint round to satisfy their curiosity, revisit a bit of shooting heritage and sometimes discover that new powders or bullets can improve on old ideas. Such adventures, however, come with obstacles that require patience and problem-solving, and like hiking a new path, the exploration itself is the destination regardless of what lies at the end.

I watched the rifle presented here languish on a local gun shop rack for two years. It looks to have started life as a Remington factory Custom Shop KS Mountain Rifle in 17 Remington, subsequently rechambered to 17-222. The rechambering appears to have taken about a half-inch off what was likely a 20-inch (1:10 twist) stainless steel barrel of slim sporter contour. At 38 inches overall and weighing 7 pounds without a scope, the rifle is a svelte package with a 12.5-inch length of pull and a trigger that snaps cleanly at 3.5 pounds without a hint of creep or overtravel.

I’m surely not the only one who picked up the rifle from the rack and thought it would make a sweet little “walking varminter,” but the reason everyone put it back is its chambering, a 70-year-old wildcat, the 17-222 Remington. The cartridge is a handloading-only affair that requires case forming, and which has little to offer over the similar factory loaded 17 Remington, so the rifle had to await just the right buyer.

A closer inspection of the price tag presented an upside for the curious handloader, the backside reading, “Dies and brass included,” so ordering expensive custom dies and scrounging up 222 Remington brass wouldn’t be an issue or add to the base cost of the rifle. Preliminary research uncovered 17-222 load data in old manuals on my bookshelf, though limited to only two IMR powders still with us today. More research indicated that modern load data for the 17 Remington might be adapted to the 17-222. I finally convinced myself there were enough reasons to reinvent this particular “wheel,” and the petite rifle was purchased.

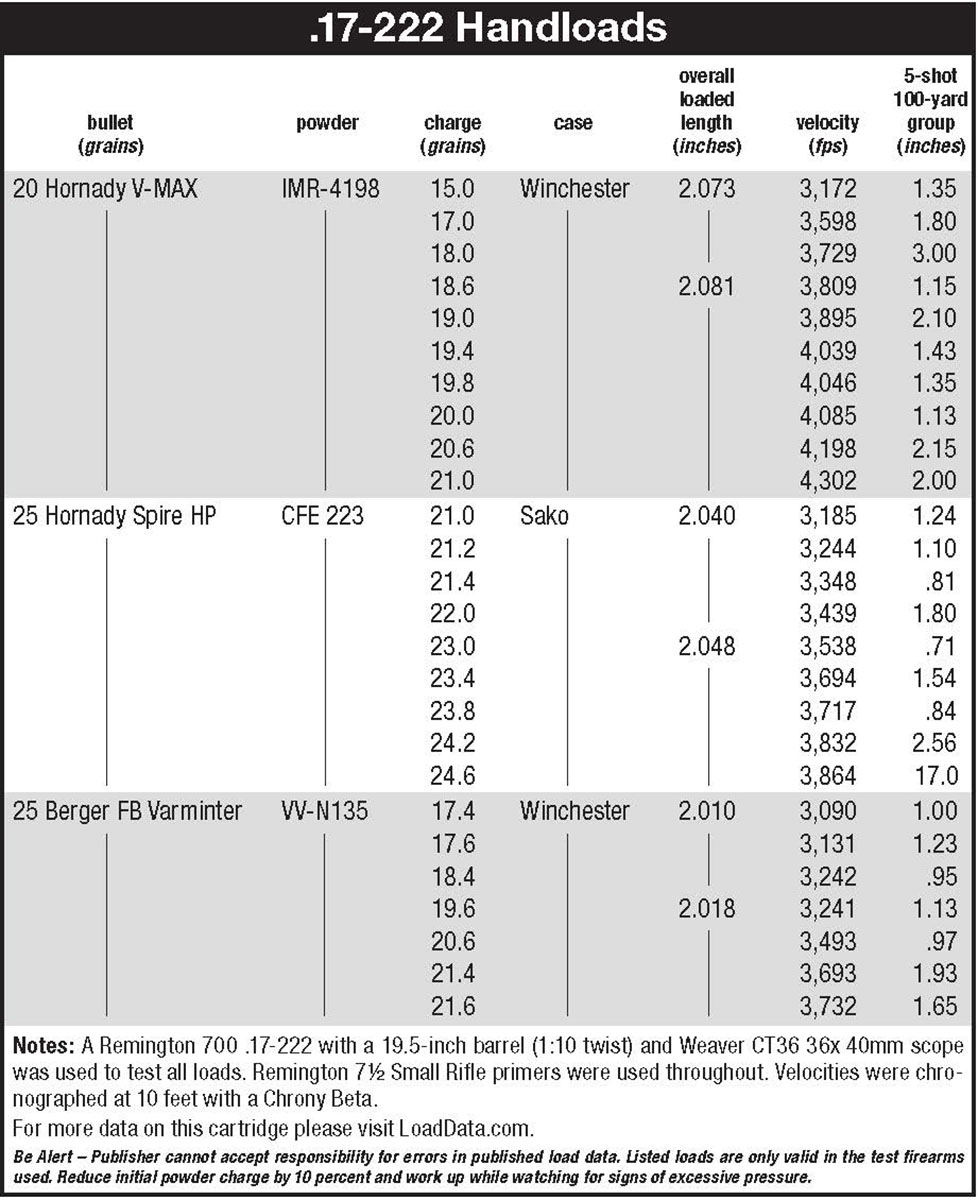

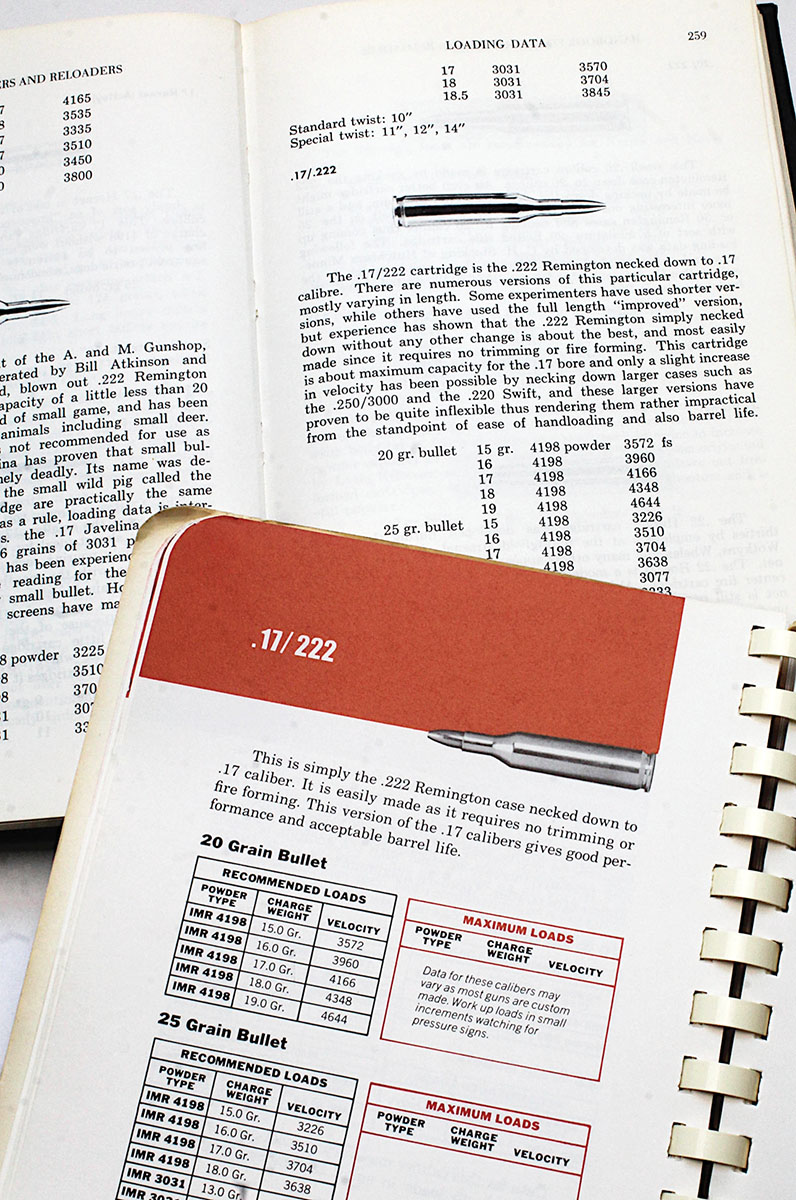

Printed modern 17-222 load data from established credible sources is nearly nonexistent; both Hodgdon and Lee currently list the cartridge, but both data sets are identical, indicating a single source. P.O. Ackley’s Handbook for Shooters and Reloaders (1962) and Pacific’s Rifle & Pistol Cartridge Handloading Manual (1968) list only two powders for the 17-222, IMR-4198 and IMR-3031. The lists recommend IMR-4198 for 20-grain bullets and both powders for 25-grain bullets. In fact, like the Hodgdon and Lee data, all 17-222 loads in both the Ackley and Pacific manuals are identical. Handloaders can use these two extruded IMR powders, of course, but perhaps we can do better with improved modern powders.

Perusing Hodgdon’s 2020 table of relative burn rates for 163 powders, there are nine that fall between IMR-4198 and IMR-3031. These nine powders are logical candidates for load development. However, choices can be dramatically expanded with a bit of extrapolation.

Case volume of the 17 Remington is close to that of the 17-222, and load data for the 17 Remington is readily available. Comparing Hodgdon and Lee 17-222 and 17 Remington data, starting charges of various powders for the 17-222, with a single exception, run 1.5 to 2 grains below 17 Remington starting charges. Given this information, it appears worthwhile to experiment with modern powders in the 17-222 by beginning with a charge about 3 grains below the published starting charges for the 17 Remington. Current 17 Remington data from several sources show 44 candidate powders for that cartridge, falling between IMR-4198 on the fast side to W-760 on the slow end. Among those, I can pull from my cabinet for this exercise two powders that didn’t exist in 1962 and that feature copper fouling reducers – CFE 223 and Vihtavuori N135. Since copper jacket fouling in the .17s was a frequent complaint of the old wildcatters, I wanted to see what new tricks these modern powders might teach an old dog.

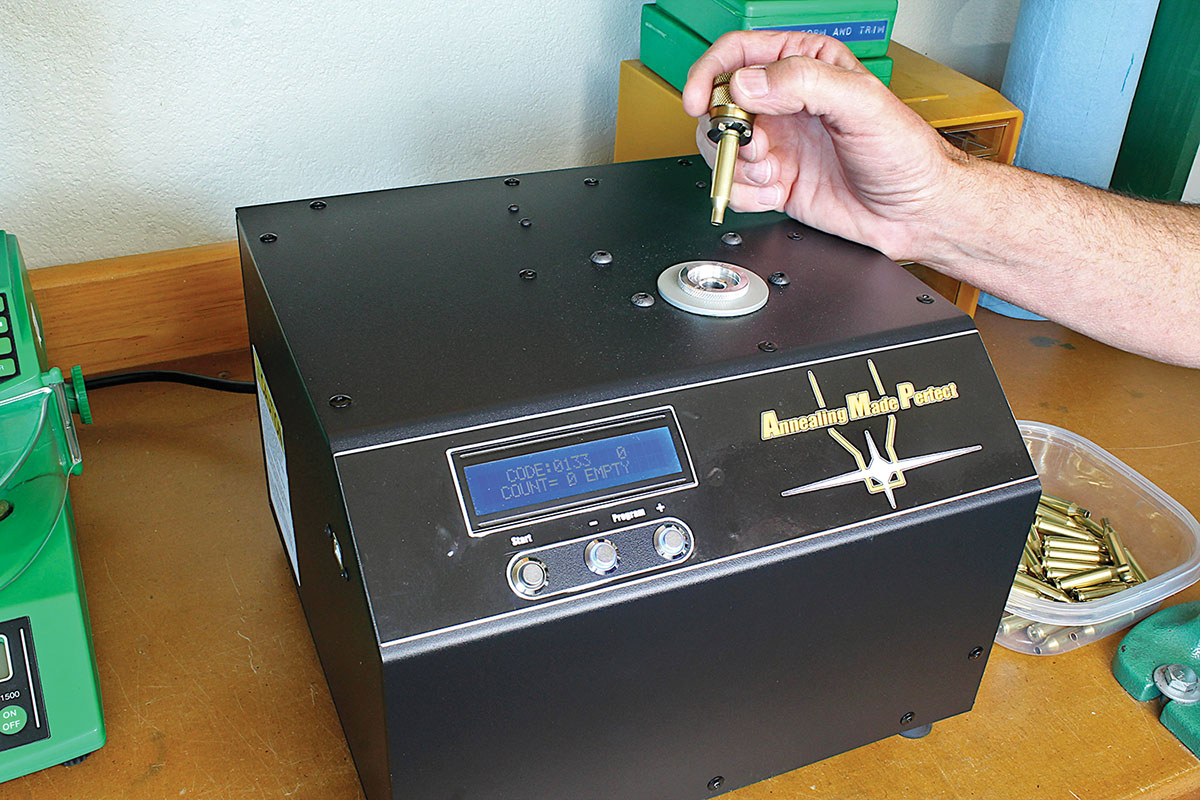

Apparently, whoever chambered the rifle also went with Ackley, as the chamber did not object to the long necks. A Sinclair Seating Depth Gauge determined maximum cartridge overall length (COAL) with Hornady 20-grain V-MAX and 25-grain Spire HP bullets and Berger 25-grain Flat Base Varminter bullets, and I made a first run of cartridges with bullets seated about .005 inch off the lands. A mixed bag of about 100 Sako and Winchester cases accompanied the rifle; after a first firing, I neck sized them for subsequent reloadings. To maintain some uniform data collection, all the CFE 223/Hornady 25-grain bullet loads went into the Sakos, and the Winchesters took the 20-grain Hornady’s and 25-grain Berger’s. All loads utilized Remington 7½ Small Rifle primers. An Annealing Made Perfect (AMP) annealing machine significantly eased case forming.

The mash-up die set accompanying the rifle illustrates the caveat emptor world of buying secondhand wildcat rifles. The set included RCBS trim and form dies to convert 222 Remington to 17-222, a Pacific full-length resizer, RCBS neck sizer and a Bonanza bullet seater. The form die reduced the case neck diameter somewhat, and the trim die reduced it the rest of the way. Unfortunately, the Pacific resizer failed to push shoulders back far enough to permit easy chambering of the case; obviously, the die and the rifle’s chamber have different dimensions. The rifle’s bolt would close on a resized case, but only with considerable force. Screwing the die down further began collapsing the case.

A few moments of cogitation presented a solution. The 17 Javelina, a wildcat contemporary of the 17-222, is also based on a shortened 222 Remington case, and I have a die set for that cartridge. After running a 222 Remington case through the form, trim and resizing dies, I ran it through the 17 Javelina resizing die, screwing the die down in small increments, trying the case in the rifle’s chamber after each resizing until the bolt closed easily on it. Voilà – problem solved. Or so I thought.

To resolve this, I adjusted the bullet seating die for a very light crimp, just enough to keep the bullet in place, and left bullets seated out for an exaggerated overall loaded length to “soft seat” the bullet ogive into the rifling when chambering. The technique frequently shrinks group sizes, and it can also help to blow shoulders forward, but such loads must not receive normal crimps as doing so can raise pressures to higher-than-normal levels. This change is noted in the accompanying table as an .008-inch increase in COAL over previous loads.

Ackley’s original 1.700-inch case length placed the case mouth right at the ogive of Hornady 20-grain V-MAX bullets, and oversize groups demonstrated the rifle’s unhappiness with that situation. So I trimmed all cases back to 1.692 inches for the third run. The 20-grain Hornady groups immediately shrank.

The rifle tended to cluster four shots together very well – as small as a half-inch – while tossing a fifth out of the group, sometimes an inch or more away. Group sizes recorded in the table include these flyers. Shooting from a heavy rest on a concrete bench and utilizing a Weaver CT36 36x 40mm scope, I am confident no flyers can be attributed to my hold. Groups are not going to tell the whole story here, anyway, as testing occurred during spring days of mountain winds that blew from zero to 25 miles per hour and circled much of the clock. However, analyzing velocity and pressures provides an idea of the potential of powder/bullet performance.

Ackley and Pacific listed a 4,644 feet per second velocity for 20-grain bullets launched with 19 grains of IMR-4198; as can be seen in the table, I experienced nowhere near that velocity with that charge, and with cases lacking signs of excessive pressure – flattened, cratered or sooty primers, bolt face marks on the head, pressure ring expansion beyond .0005 – I continued onward with increased charges to see if the powder would reach that 4,644 fps velocity. In this rifle and with this combination of components, it did not. I maxed out at 4,302 fps using 21 grains of IMR-4198. Stepping up the powder charge doubled group sizes and cratered primers.

As proposed at the beginning, the performance of the wildcat 17-222 has little to offer over the 17 Remington factory cartridge, with best 25-grain bullet accuracy at around 3,500/3,700 fps and perhaps 4,000 fps for the 20-grain bullet. Winds were a factor affecting grouping, but the unspectacular groups are also a function of the rifle’s slender barrel heating with repeated firing. I can also point at the electronic powder scale’s plus/minus 0.1 grain tolerance as a factor when loading such small cases, which may account for those routine flyers.

As for new tricks, the Berger and Hornady bullets performed well, the flatbase bullets seating in cases without complaint and showing no inclination to shed jackets with velocity. The modern CFE 223 and VV-N135 powders have the advantage of youth over IMR-4198 in their copper fouling reducers and smooth, consistent metering, and both turned in smaller groups than did IMR-4198. Certainly, the potential is there to shrink groups with further powder and bullet combinations.

There are a few takeaways in reinventing this “wheel,” if not screeching velocity and one-hole groups. That’s usually the case when stepping beyond the routine to explore new – or old – territory. Besides, the basic rifle is a quality, trim little package for varminting and small-game hunting, and maybe rechambering to 17 Javelina.