250 Savage Ackley Improved

Loads for a Classic Cartridge

feature By: Jim Matthews | October, 20

There was a recent post on an online shooter’s site where someone asked what led to the explosion in popularity in the 6.5mm, especially the 6.5 Creedmoor. In some ways, it was driven by the same criteria that led to the development of the 250 AI by rifle fanatics of a different generation.

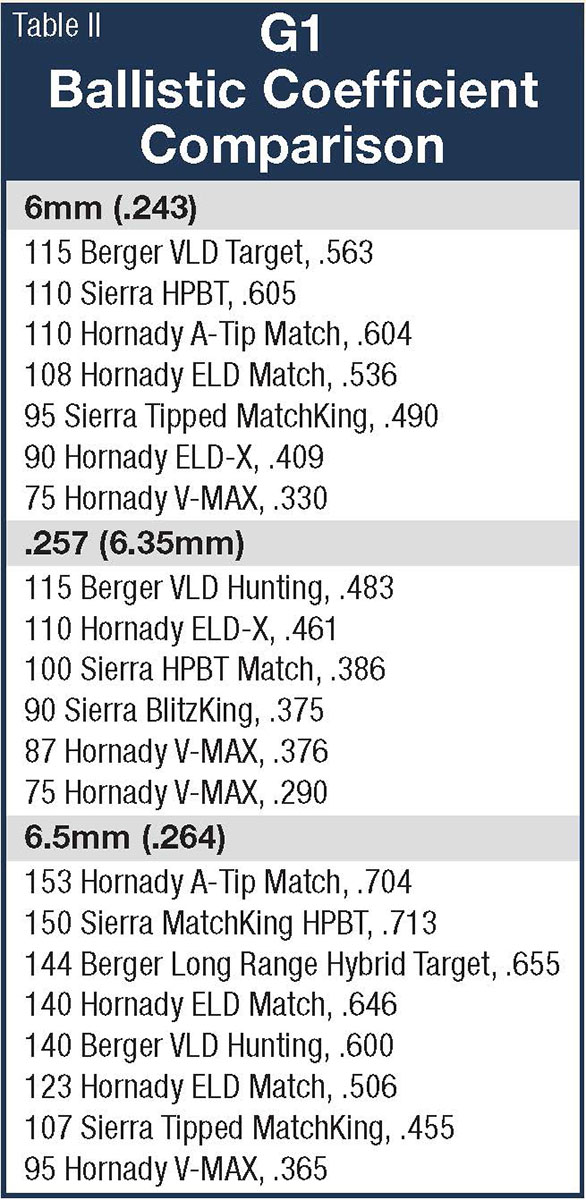

But in the 1930s, 40s and 50s, a 1:10 twist barrel on the .25-caliber round was optimizing what was currently available at the time. This was largely the pre-6mm/6.5mm era, and the .25 caliber had the most readily available aerodynamic bullets of the day (spitzers, even some with boat-tails) up to 120 grains. These would stabilize in those common 1:10 barrels of that era. The .25-caliber bullets also spanned the spectrum from light slugs designed for varmints to heavy big-game bullets with high (for that era) BCs that were effective on game.

This was the time when riflescopes were just becoming common among hunters. They were looking for cartridges that could take game as far as they could see them clearly in their new riflescopes, and they wanted the least amount of bullet drop possible so they could make hits at 200 to 350 yards – maybe even 400 yards if they had a good rest and had done a lot of shooting.

This criteria is what eventually made the 257 Roberts and 25-06 factory rounds so popular with hunters of that time. They all kicked less than equivalent guns, even less than the wildly popular 270 Winchester, and they could be reliably used to hit and kill game with shots at more distant ranges. This was also a time when a lot of hunters were “one-gun guys,” so a rifle that was as good for varmints and big game was a plus.

The 250 Ackley Improved was a multi-purpose round, and it was taking advantage of the latest technology. Its parent case was the gee-whiz cartridge of the shooting world when the 250 Savage was announced in 1915. It had a staggering velocity of 3,000 fps. The 250 AI kicked that speed up, reaching about the maximum velocity obtainable in the .25 caliber with powders of that era.

Today’s shooters are clearly aware that speed comes with a price: recoil. We all shoot better when not getting beat around by a hard-recoiling gun. As varmint hunters know, hard recoil’s definition changes as the volume of shots fired increases. Rangefinders and precision optics that have trajectory compensation dials and precision windage and elevation adjustments and/or reticle marks, allow for the use of milder, low-recoiling rounds.

When you can know a prairie dog is precisely 637 yards away and you can dial in the exact hold at that distance; when you have a rifle that will shoot a 4-inch group at that range, and you can figure that wind drift in the prairie breeze on your high BC bullet will only be from 6 to 8 inches at that distant target, you have a very good chance of killing that varmint on the first shot. That shot would have been luck just 25 years ago. Today it is common.

Not a lot of cartridges have spanned yesterday’s and today’s technology advancements, but many of the once uber-popular .24s to .25s could if used with contemporary high BC bullets and fast-twist barrels. If 243s and 6mm Remingtons were made with 1:7 or 1:8 twist barrels, they would be the equal of the 6mm Creedmoor with the new crop of bullets. The problem is that with 1:10 twist barrels, many of the high BC bullets will not stabilize. Bullets going through targets sideways do not produce good groups or shoot well past 100 feet. It was easier to bring out new cartridges than deal with the nightmares of a 243 Winchester loaded with 110-grain, .600 BC bullet would cause when shot in older guns.

This brings us back to Ackley’s 250 Savage Improved. The improved old Savage case is a near image of 6mm and 6.5mm Creedmoors. They look like kissing cousins, and the .25 caliber is actually an interesting compromise between the 6mm and 6.5mm rounds.

Historically, the 250 AI is one of Ackley’s better improved rounds. The 1915-vintage .250 had a tapered body and modest shoulder angle to function through the Savage 99 level action. The Ackley version actually increases the powder capacity over the parent case significantly by shortening the neck and blowing out the shoulder and case sides. My measurements show that the 250 Savage holds about 45.5 grains of water (depending on brand of case), while my 250 AI cases hold around 52.0 grains of water. That additional 6.5 grains of space equates to a little more than a 14 percent increase in capacity, and the short neck creates more usable powder space in the cartridge.

Maximum loads in my bolt-action 250 Savages will push a 75-grain bullet at 3,200 fps. My 250 AI will comfortably push that same bullet 3,500 fps. You might read some internet expert say those top levels can easily be exceeded 100 to 200 fps, pushing the 250 AI to near-25-06-like velocities because they are so “efficient.” What? Three words of advice: Don’t do it. If you are getting velocities over those in the table – which you need to work up to carefully – you are asking for trouble.

The 250 AI and the 257 Roberts have nearly identical case capacities, with Roberts cases having no more than .5-grain more water capacity in the brass I’ve measured. I have been using 257 Roberts starting loads as the beginning point for most of my load development and only exceeded top-end Roberts’ loads/velocities if there was no case head expansion and no other signs of excessive pressure (stout bolt lift or extractor hole marks on the brass). Most of the time, you are better off staying within the Roberts load data or below, because you will often encounter pressure signs below the Roberts maximums.

When I first started shooting my 250 AI about a decade ago (and a 250 Savage about a decade before that), it was problematic to find 250 Savage brass. When I could find it, the price was 50 to 100 percent higher than 22-250 Remington brass. So, most of my 250 AI brass was made from 22-250 cases, and the neck was simply opened up in Redding AI sizer die, fire-formed, and then reloaded.

For fireforming reformed 22-250 cases, I usually load some Hornady 117-grain roundnose bullets ahead of a very mild charge of H-4895. I seat the bullet well out of the case, near rifling to help hold it against the bolt face when fireforming. I’ve never had headspacing problems with brass made this way.

Today, it is just as easy to use 6.5mm Creedmoor brass. I neck it down the slight amount needed to .25 caliber, trim the case about .015 inch, and fireform it. The trick here to get consistent cases is to adjust the sizing die incrementally so it will leave a slight auxiliary shoulder on the 6.5 neck for fireforming. You want the bolt to be able to close on the reformed and trimmed case with just a bit of resistance. When the fired case emerges you will see that the base of the shoulder has been moved forward, the neck shortened, and the shoulder has a sharper angle than the original Creedmoor case. I have also used 6mm Creedmoor brass much like I do with 22-250 brass, and it also requires a slight trimming before fireforming.

The difference in maximum case length between the 250 AI and the Creedmoors is very slight – 1.920 inches versus 1.912 – with the 250 AI being slightly shorter. I usually trim cases to 1.905 inches and cases I’ve shot five or six times show very little lengthening, with none requiring trimming so far.

There is no question that some shooters have already made “6.35 Creedmoors,” but the 250 AI case is a more logical alternative because there are already a lot of reamers in gun shops across the country. (Three of the four local gunsmiths I know had them when I called to check for this story.) There are also a lot of nicely-made older rifles in the AI banging around that can often be picked up at reasonable prices on used gun racks or at gun shows. The sad truth for the original owner is that wildcats often resell for less than equivalent rifles chambered for a factory round.

For varmint hunters, there is a wide range of .25-caliber bullets that will cover most needs. The loading table with this story has everything from close to midrange, explosive performance loads with bullets like the Sierra 70-grain BlitzKing and Hornady 75-grain V-MAX, up to the long-range abilities of the Hornady 110-grain ELD and the 115-grain Berger VLD Hunting that will make 500- and 600-yard shots very doable.

My Model 700 with its Shilen barrel particularly likes the Hornady 75-grain V-MAX at about 3,500 fps and the Sierra 90-grain BlitzKing at 3,300 fps. I initially thought the 115-grain Berger might not stabilize in the 1:10 twist on the rifle (Berger says a 1:9 is optimum.) but the group I shot with this bullet and SUPERFORMANCE powder was among the best I ever shot with the rifle.

I also don’t think a single powder or bullet used showed extreme velocity spreads greater than 50 fps, and many loads hovered in the low 20s for five shots. The new Shooters World Long Rifle powder showed low extreme spreads and produced a couple of good groups with different bullets in initial testing. The plethora of powders available in the ideal burn rate for the Creedmoor class of rounds opens up a world of experimentation to find ideal combinations for the 250 AI. These loads barely scratch the surface.

Note that there is a reduced velocity load. I always develop at least one load at lower velocity for volume shooting at close varmints and plinking practice. I tinker until I find a load that shoots to the crosshairs at around 50 yards using the same scope setting as a high velocity load sighted in to shoot at more distant ranges.

If a varmint shooter has a hankering for a long-range shooter with even less recoil than the 6.5 Creedmoor and equal or better performance on distant targets than the 6mm or 6.5mm rounds, a 250 Savage Ackley Improved might just make sense.

The idea made sense from the 1930s through the 1950s, when a lot of 250 Ackley rifles were made on short actions for poking holes in varmints and deer-sized game in those long-ago days. Perhaps we are coming full circle and breathing new life into this old wildcat.