Varmint Loads for the 30-06

All of the Reasons for Shooting Big-Game Rifles in the Off-Season

feature By: Jim Matthews | October, 20

That was common. A lot of working-class hunters never owned more than one centerfire rifle; a condition forced on them by economics. While falling a little out of favor today as the one, do-everything cartridge, the 30-06 is still one of the most popular rounds on the market, and it is still the round of choice for many big-game hunters across the country. With the possible exception of the big bears, the 30-06 will handle any big game in North America with authority.

Wanna know a little secret? It is hard on varmints. Just about all the rifles chambered for this cartridge are accurate enough to consistently make hits on tiny varmints out to 200 yards, and critters the size of prairie dogs and wood or rockchucks out to 300 yards. Coyotes are in serious danger about as far away as most hunters will attempt shots on these predators. Many rifles are tack drivers, even with light barrels, and will take predators at distances equal to any cartridge/rifle factory combination.

Is it an ideal varmint cartridge? Of course not. Recoil can be pretty abrupt for extended shooting sessions on ground squirrels with standard power loads.

However, there is a huge benefit to using a rifle you will press into service during the fall for big-game hunting. Having the boomer at your shoulder for at least some of your varmint hunting during the spring and summer will give you a familiarity with that rifle across a wide variety of field shooting conditions. Range shooting will never give you that kind of experience.

It really shows when a hunter has not spent a lot of time in the field with his rifle. For a couple of springs, I hosted a series of unguided hog hunts on a big California ranch. I often tagged along with hunters when they were driving dirt roads and walking ridges looking for wild pigs. And since the ranch was packed with the hogs during that era, finding game usually was not a problem.

When pigs were spotted, it was amazing how unfamiliar many of the hunters were with their firearms – how they struggled to quickly find a field shooting position, and then to acquire the game in the sights and shoot quickly before it disappeared. When they did shoot, shots often were sent all over the hillside. Follow-up shots were slow and many hunters had trouble operating the action.

Rifles had often not been sighted in – or a different ammunition was being used from the one used at the range. And most had never practiced shooting from a kneeling or sitting position on uneven terrain. Taking two steps to brace against one of the many oak trees on the ranch never occurred to many of these hunters. It was like an alien nightmare for me. How could anyone come on a big-game hunt be so ill-prepared for that moment of truth? I learned firsthand the stories I’d heard from guides for years were true.

On my most recent hog hunt, I had been riding around with a young guide, and he’d been giving me grief about how I must have been getting old, lagging behind and not shooting while others in the party blazed away. Soon, I was the last one – everyone else had tagged out – and it was the final morning of hunting. All morning I had been giving the young guide grief back, about how a good guide couldn’t get even a gimpy old man into pigs. Twice that morning hogs had given us the slip. It was getting late in the morning and the pigs were not moving much, already resting in shade and cover for the warm part of the day.

Quickly I chambered another round, swung smoothly ahead of the pig and shot again just as it reached some brush. It disappeared with a squeal and a crashing of brush as it rolled to the bottom of the canyon.

“I haven’t seen you move that fast the last three days,” the young guide teased me, grinning. I pretended to glare at him.

“I was just waiting for an opportunity to shoot a hog in the bottom of a steep canyon so you could get him out for me.” Now he was the one glaring.

It turned out he could get the truck to the top on the ridge on the opposite side of the canyon, and he had more than 400 feet of rope and cable that made the job a snap.

Riding back, the kid smiled at me and said, “I wish all my clients were like you. How did you learn to shoot like that?” We talked about varmint hunting all the way back to the ranch house and walk-in cooler.

Growing up hunting in Southern California during the late 1960s and early 1970s, I was around during the last big population explosion of black-tailed jackrabbits in the Mojave Desert. It was nothing to see and shoot at 100-plus jackrabbits during a day of walking the creosote flats and hillsides. Loading up every piece of brass I had with fast-stepping hollowpoints in my 243 was how I learned to shoot running game.

Every possible shooting situation, in every kind of terrain and in all kinds of weather, were experienced. All of my shooting for most of those years was done with big-game rifles loaded with either cast bullets or high-velocity varmint bullets. I shot 60, 70 and 85 grainers in my 243, 90s and 110s in my 270, and loaded thousands of varmint rounds of 30-06 for my uncle and his hunting buddies, who were my hunting mentors.

Over those years, I learned how to shoot in the field. I learned my firearms, how they functioned and where they shot. There is no better teacher for those skills than varmint hunting. That experience has paid off during big-game hunts for 50 years.

This is why I suggest that even the most avid varmint hunters utilize their big-game rifle(s) for at least some varmint hunting, or at least during portions of hunts each year. When I inherited my uncle’s 30-06, a wonderful old Winchester Model 54, I vowed that I would keep it shooting and use it each year. I long ago settled on a low-recoil cast bullet load for hunting with this gun, to which I fitted a vintage peep sight from the 1930s. Until California banned lead ammunition for all hunting, this was my “out-to-100-yards” ground squirrel rig. I am now tinkering with other bullet options for hunting, but those lead loads are still breaking rocks all over the desert.

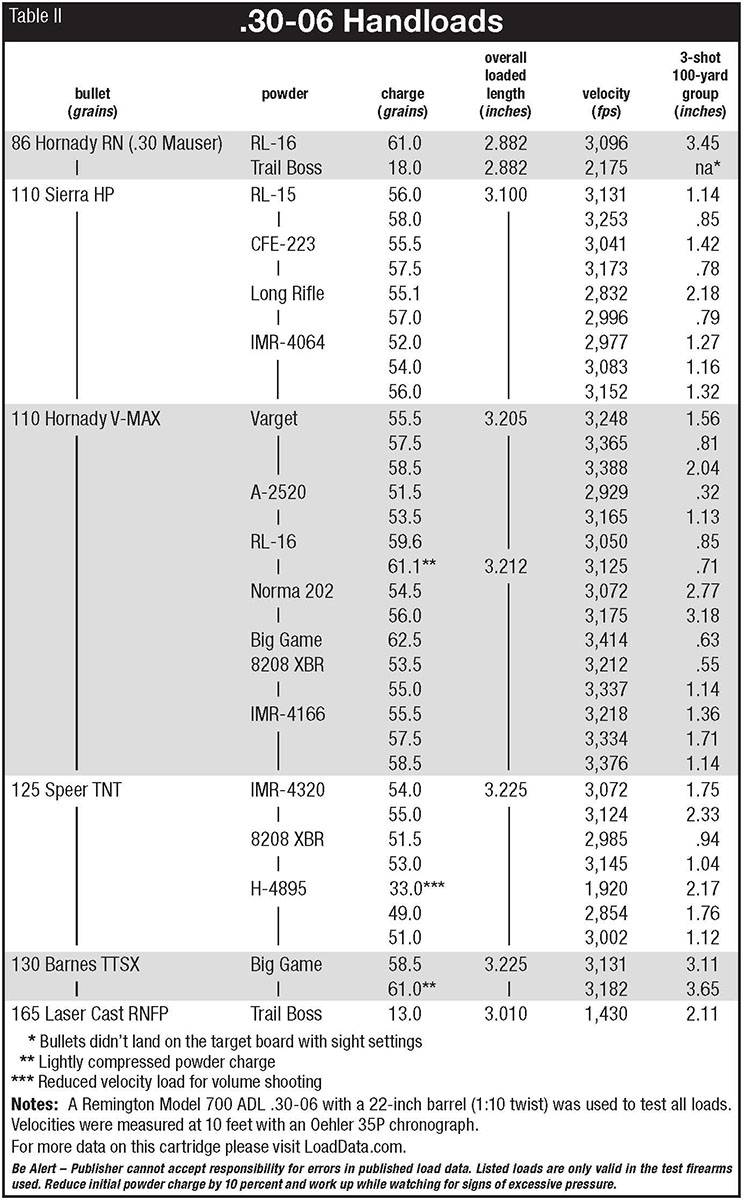

Recently, my youngest brother-in-law retired and has been traveling, shooting and hunting more. He asked me to work up some varmint and big-game loads for his 30-06 Remington Model 700. The load table with this story show the results of those efforts for varmint loads.

The bullet companies continue to expand options for .30-caliber varmint hunting and many of the old standby bullets are still made in weights from 100 to 150 grains designed primarily (or suitable) for varmints. The three most common varmint bullet weights are 110 grains, 125 grains and 130 grains. There are also a number of uber-fragile bullets on the market that have recommendations for not exceeding certain velocities, which are great for knocking down recoil while still having explosive impacts on varmints. Finally, cast lead bullets at rimfire velocities are a great option to reduce recoil for volume shooting, especially for new hunters who might be sensitive to recoil.

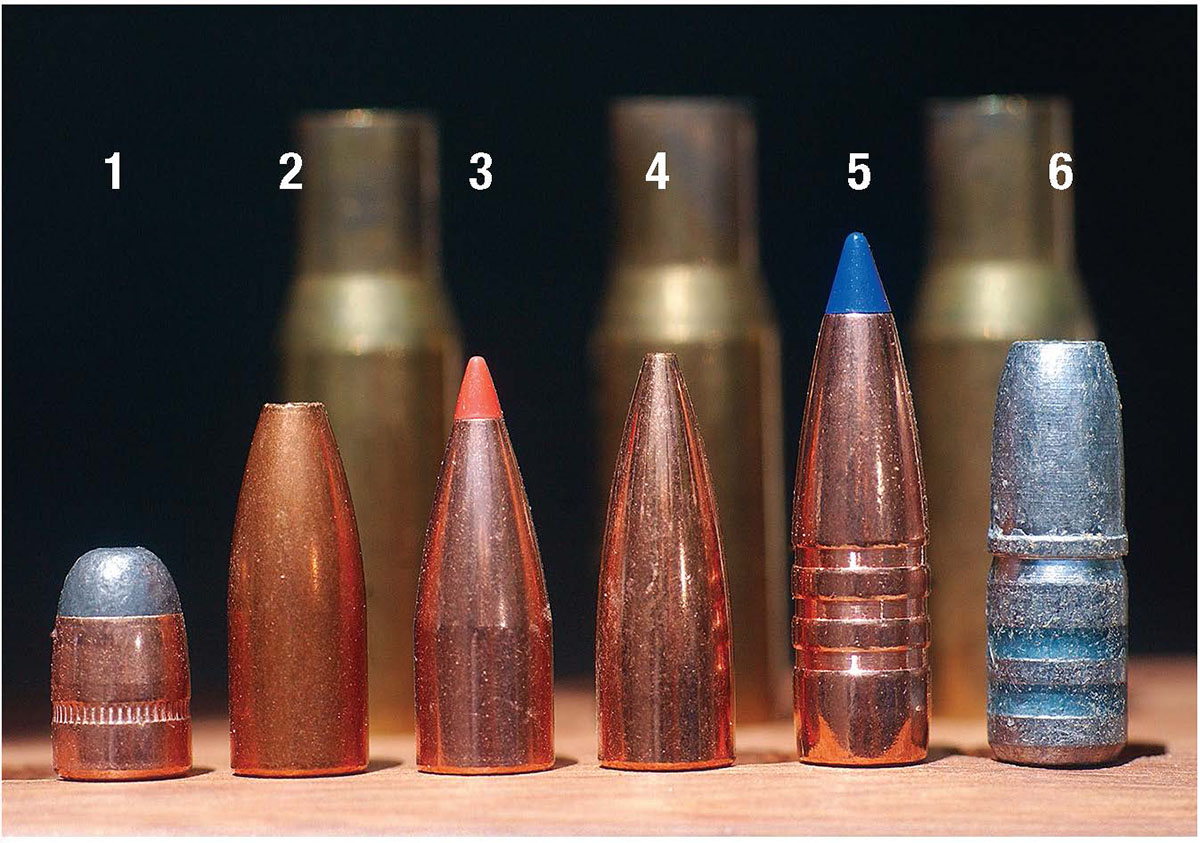

For this story, I chose six bullets from 86 to 165 grains. The lightest was Hornady 86-grain roundnose actually designed for the 30 Mauser pistol. I was initially worried that this light, fragile bullet might come apart at higher velocities, but in my limited testing, it did fine up to 3,100 fps. Care must be taken with this stubby bullet to make sure it seats correctly and doesn’t cock slightly and crush the case mouth. Probably the most popular varmint weight in .30 calibers, I selected two options that weighed 110 grains. The first was a classic Sierra 110-grain hollowpoint that has been made for many decades. It was the bullet I used a lot when loading for hunting mentors, and we shot a lot of varmints with this bullet that has explosive performance. It’s not a good choice if you want to save pelts, but that is probably good advice for most of these bullets.

The second was the newer Hornady 110-grain V-MAX. There was also one 125-grain slug in the mix, the old Speer TNT hollowpoint my uncle favored in his 30-06, and a 130-grain Barnes TTSX, a lead-free option that could serve for deer, antelope and varmints. Lastly, I loaded a batch of Laser Cast 165-grain RNFPs that have proven so fun in the old Model 54.

Here I used 14 different powders with the five bullets. Both old and new powders are in the list of 36 loads tested. While only three-shot groups were fired, eight of those 36 loads produced sub-MOA groups at 100 yards. While one of those groups (the .32-inch cluster) was clearly a fluke where my wobbles compensated for my wiggles, there probably would have been a couple of smaller groups except for shooter error.

Extreme velocity spreads rarely exceeded 50 fps for any powder, and a number of the old powders, especially IMR-4064 and IMR-4320, had extreme spreads of less than 20 fps. Not surprisingly, the latest Lyman reloading manual lists those powders with two bullet weights as having the best potential accuracy. My best accuracy was scattered across the powders, but IMR-8208 XBR produced two of the best groups with both 110-grain and 125-grain bullets. Twist my arm, and I would probably tinker more with Varget, Big Game and IMR-4166 for a nice combination of top velocities and accuracy. The new Shooters World Long Rifle also bears more experimentation because I started with very light loads, having no factory data for the light bullets with this powder, but extreme spreads were low and it produced one great group.

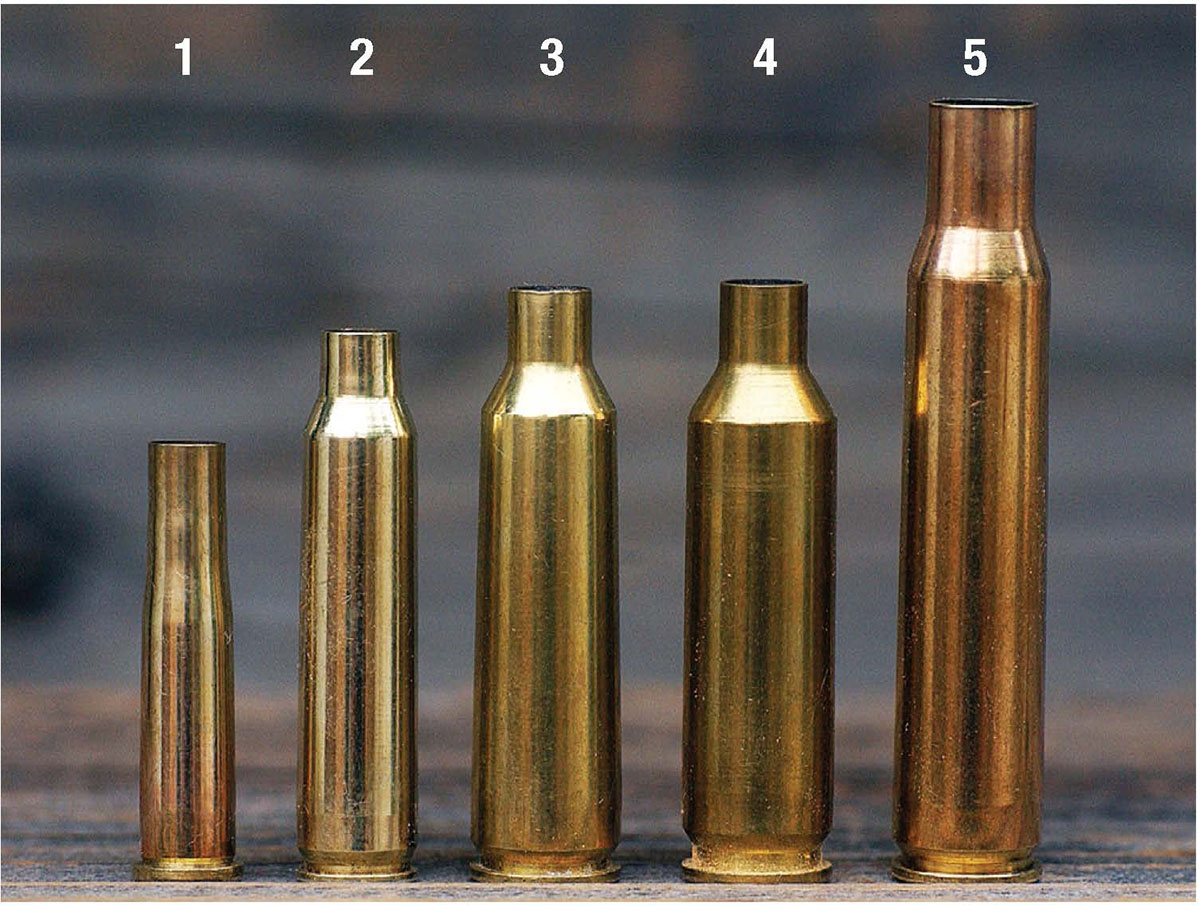

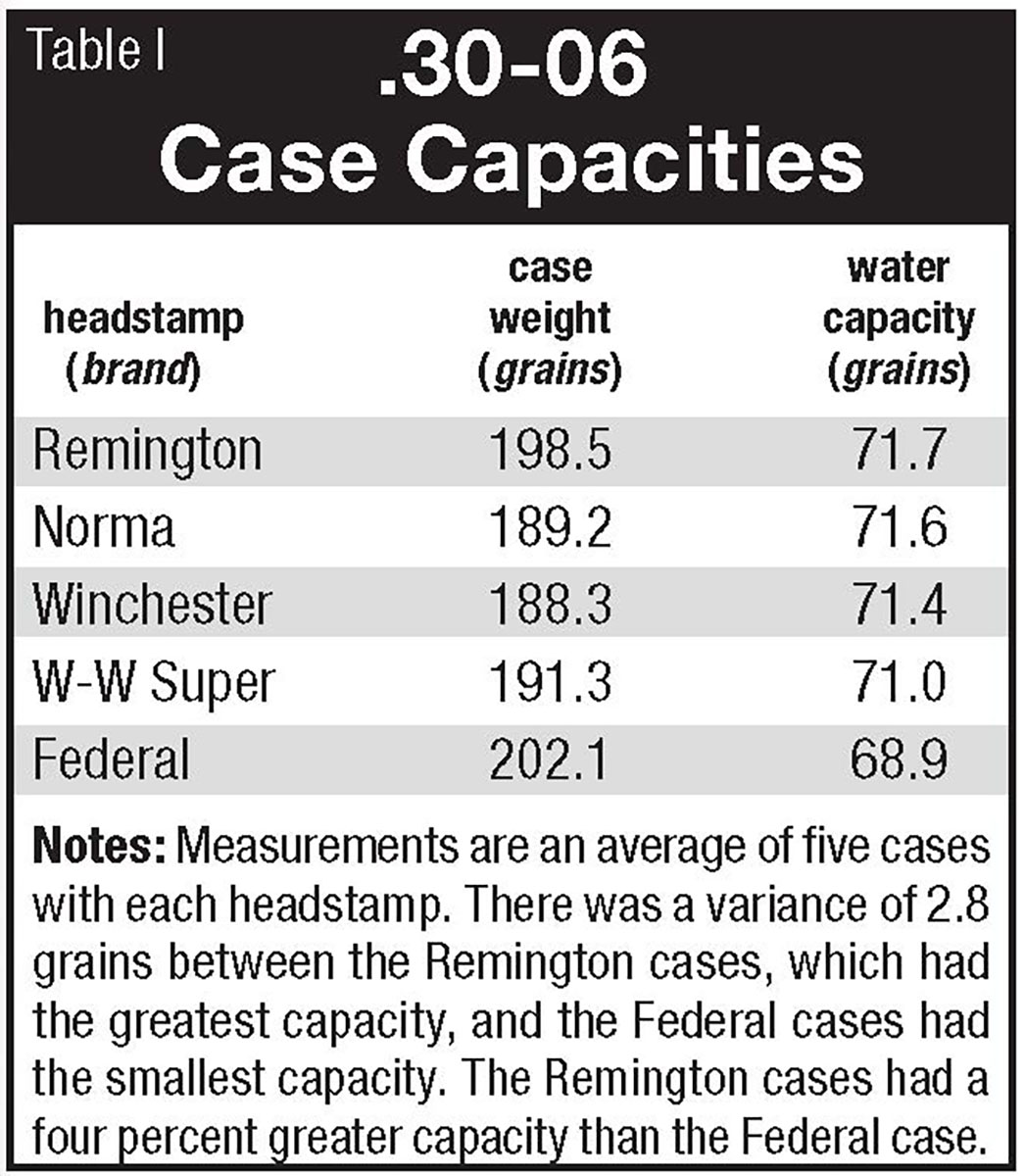

Most of these loads are relatively mild, midrange loads, with only one or two approaching a charge weight listed as maximum in a number of reloading manuals. However, caution is especially advised for the venerable old cartridge. Brass has been made all over the world and used through two world wars. I still have a lot of old military brass from the 1950s and 1960s that I still use – I don’t think the stuff will ever wear out with light cast bullet loads. I used five types of brass with different headstamps, and the cases with the lowest capacity held four percent less powder than the brand with the most capacity. There are a lot of “improved” wildcats out there that don’t increase the case capacity any more than that over the parent round. This data just shows that caution is even more important in working up loads, and it is critically important not to believe loads are safe between different lots or brands of brass.

A lot of varmint hunters are likely to have a 30-06 in their gun safe. Whether it’s an inherited heirloom like my Model 54 or a newer rifle picked up for big-game hunting, shooting it for varmints has benefits that go far beyond nostalgia or checking sight or scope settings.