22 Hornet

Even today it has plenty of sting.

feature By: Stan Trzoniec | April, 18

The beginnings of the Hornet can be traced to around 1893 or 1894, to a writer of the time named Reuben Harwood in Somerville, Massachusetts. He set about developing what some people believe to be an early Hornet. Using the 22 WCF cartridge, he loaded a 48-grain bullet with, of all things, a “duplex” load of powder consisting of a blend of smokeless and semi-smokeless propellants, which he claimed gave a velocity of around 1,900 fps. This cartridge looked nothing like our current 22 Hornet (ballistically or otherwise), as it was based on the 22 WCF (22-13-45).

Looking back in research material, it seemed like the Hornet we know today took a long time to get going. There was a similar cartridge imported from Germany, the 5.6x35R Vierling, loaded with various bullet weights from 39 to 46 grains. Then the Ordnance Department at Springfield Armory, including Woodworth, Woody, Whelen and Wotkyns, worked out many special loads on the 22 WCF case.

Other notables, Sisk, Donaldson and Niedner, also worked on the concept using the 22 WCF case and used specially developed 2400 powder, but it wasn’t until Winchester first took note of the cartridge around 1930, later cataloging the 22 Hornet as we know it today in 1932, that it started to be noticed.

While some shooters were lying in wait, saying Winchester held back on a rifle for its new cartridge, the bolt-action Model 54 was launched only a year after the formal introduction of the commercially available 22 Hornet cartridge. Later the Model 70 came on board, with Savage following suit and Stevens not far behind.

Before getting too far into the loading discussion, let it be said that I still consider the Hornet to have a usable range of more than 150 yards, perhaps stretching out to maybe 200 yards on a good, windless day. For use on eastern woodchucks and crows, the cartridge fares very well. The 22 K-Hornet designed by Lysle Kilbourn, a blown-out version of the original Hornet with a little more velocity (about 100 fps) is used for longer distance shots. For larger game, varmint cartridges like the 224 Weatherby, 22-250 Remington or the 220 Swift are preferred.

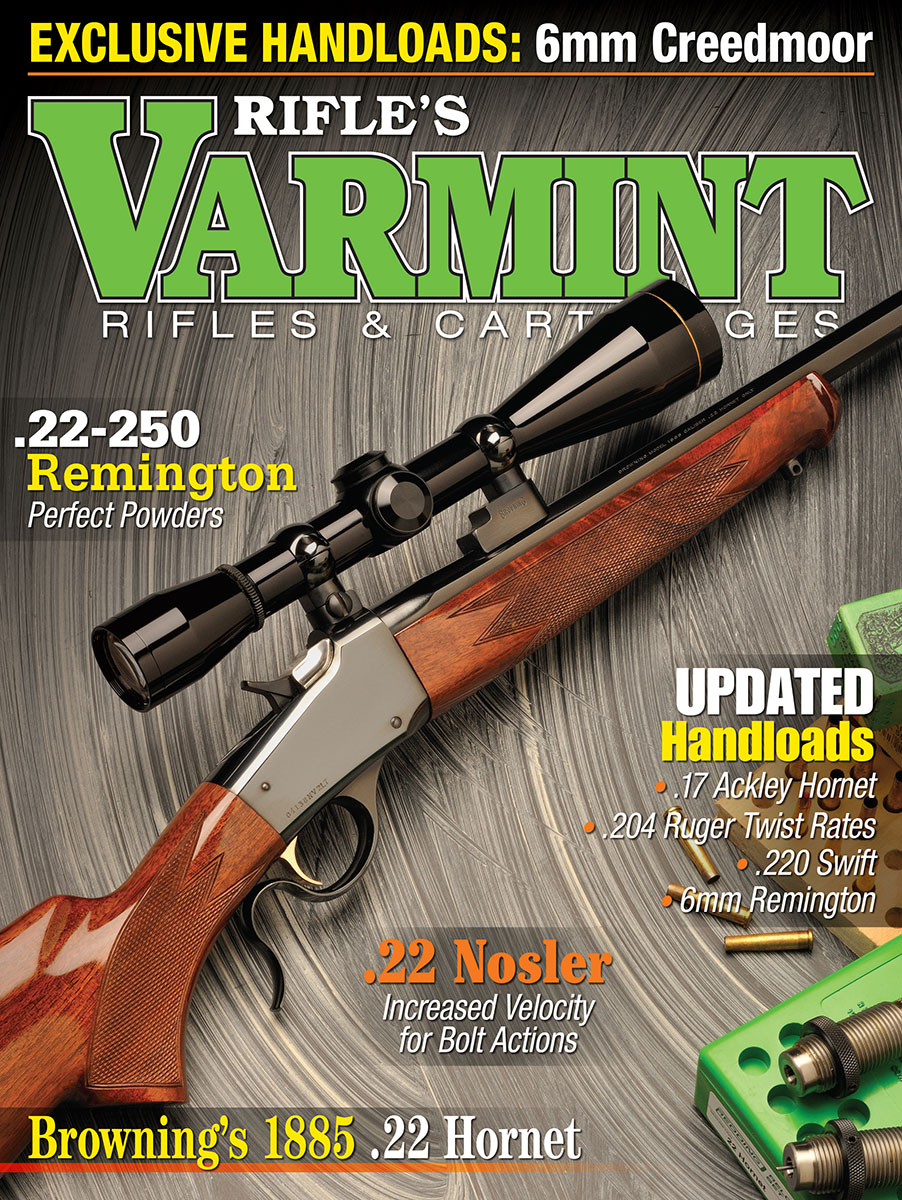

The Hornet is a fun cartridge with mild recoil, and barrel lifespan is as good as any rimfire round. While I have always had a 22 Hornet rifle in my rack, it was not until the announcement by Browning of its laudable Model 1885 Low Wall Hornet that I jumped back into the single-shot fray. The 1885 22 Hornet single shot is a pleasure to use when testing handloads or varmint hunting. With a select walnut stock with a bit of crotch feathering, and a forearm to match, it was worth keeping for sure. Checkering was first class, the stock was profiled in a “modern classic” design, and for field use I opted to have a thin buttpad installed over the plastic buttplate supplied. The metalwork was highly polished, the barrel was octagonal in shape, and the operation lever was easy to use and pivoted smoothly. The trigger could be adjusted down to 3.5 pounds; a bit lower would have been better. A Leupold M8, 6x42mm scope with Duplex reticle was installed.

For varmint hunters that do not want to venture into the world of handloading for the 22 Hornet, there is a wide variety of factory ammunition available from a number of sources to suit various needs. Checking factory catalogs and the Internet revealed that Winchester, Remington and Hornady still offer ammunition in a variety of bullet weights and velocities.

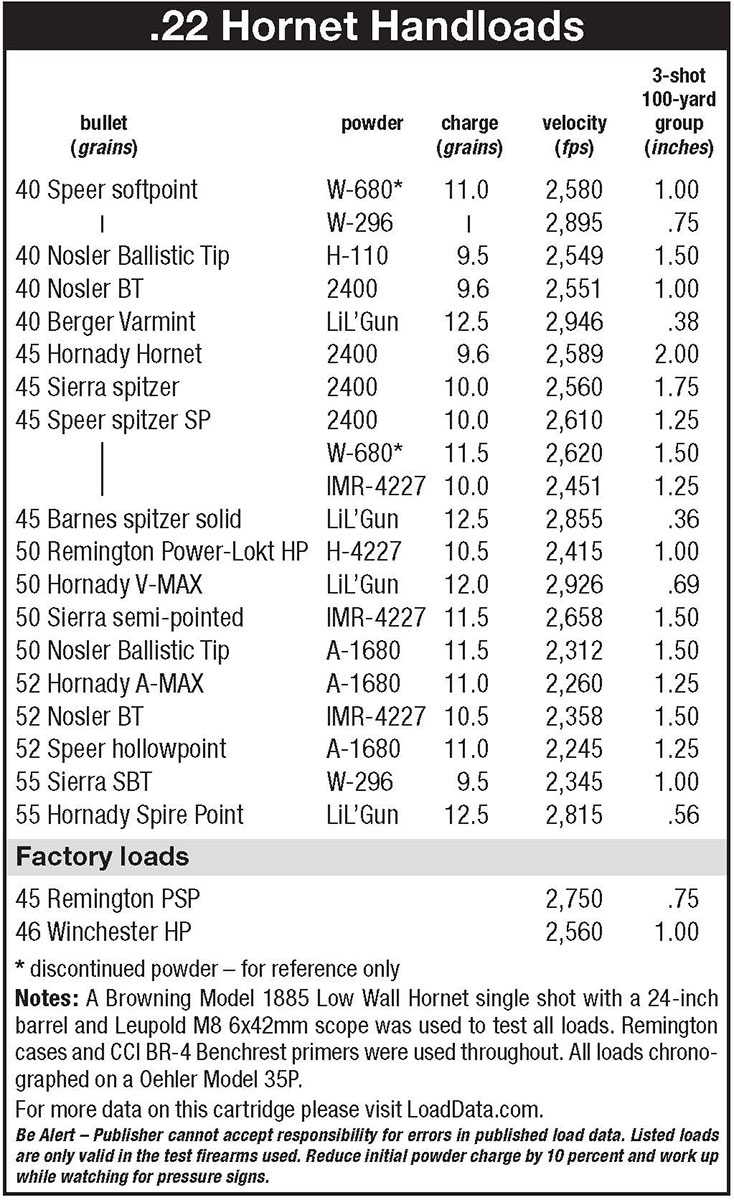

With that in mind, I shot Remington and Winchester commercial ammunition through the Browning Low Wall before using handloads. The reason here is obvious – to break in the new barrel a bit and sight in the scope without expending powder and bullets until I had the time for more serious shooting and data gathering. Interestingly, Remington’s 45-grain pointed softpoint factory load with a velocity of 2,750 fps printed nice and neat groups with a mean of around .75 inch at 100 yards. Winchester’s 46-grain hollowpoint load almost matched that with one-inch groups at 2,560 fps, while the company’s 45-grain softpoint and Remington’s 45-grain hollowpoint provided 1.25-inch groups.

When it comes to primers, CCI BR-4 Benchrest Small Rifle primers have always worked well. While I have never done exhaustive testing on whether regular primers or benchrest variants are substantially better in such a small case, I get consistent results when using benchrest primers for all my varminting chores. While I prefer the CCI brand, other companies make a similar product for precision shooting.

Dealing with powders and a case holding around 12.2 grains of water, it doesn’t take long to see that handloading the Hornet cartridge is economical. Using a charge of about 10.0 grains of Alliant 2400, around 700 handloads can be squeezed from a one-pound bottle. At $23 per pound, you are looking at about .032 cents per round. In my experience, “Hornet” powders start with Alliant 2400 on the fast side and lead to Accurate 1680 (in lieu of the now-discontinued Winchester 680).

For my needs, over the years and with many rifles, the list included Alliant 2400, originally made for the Hornet, and Hodgdon’s LiL’Gun has proved to be the most accurate with the highest velocities of all the powders tested. It is now my go-to propellant for the Hornet. Close on its heels is Hodgdon’s H-110. Along the same lines, Winchester 296 was developed for magnum cartridges, but it fills the bill in the Hornet as well, and it has usually placed second during my bench testing.

In 1935, DuPont introduced its first run of IMR-4227, and according to Phil Sharpe, he loved using it in combination with a 45-grain bullet in the Hornet, and later I liked it in the 221 Fireball. Checking Sharpe’s data from years past showed he achieved 2,410 fps with 10.8 grains of IMR-4227 in 1941(!), while I got 2,451 fps from only 10.0 grains. I enjoyed it too, but never could get the tiny groups achieved with other powders. Accurate 1680 is another choice in this powder range, but it fell a little short for those who like sub-minute of angle or smaller groups downrange. For handloaders who might question the use of Winchester 680 powder, the loads shown in the table go back quite a few years and are used for reference only (unless you have some on the back shelf).

With a good quantity of once-fired brass to work with, each case was checked after full-length sizing, making sure they all came to 1.393 inches – trimming them if necessary. After that, neck sizing was required. I adjust the die so only the area above of the tapered shoulder comes in contact with the die. For the 22 Hornet I use Redding dies, but in the past I have used other brands with equal results. Checking the sizing die, its expander measured .221 inch, which is perfect for a good grip on .224-inch bullets used in modern rifles like the Browning. I also slightly chamfer the case mouths.

Bullet selection is largely based on how the manufacturer’s bullet performed in the past, its design, and how a bullet might perform a given task. When it came to bullet weights, I found that the 45-grain samples seemed to be the optimum weight for the Hornet, just as I find the 55-grain weight great for the larger .22 centerfire cartridges. Sure, the lighter bullets gain a slight edge in velocity, but on average, groups seem to be in the same ballpark. The heavier 50-, 52- and 55-grain bullets seem to give larger group sizes. As noted in the table, bullets tested ran the gamut: Speer, Nosler, Berger, Hornady, Sierra and Remington.

Working down the list of 40-grain bullets, the Speer softpoint loaded with 11.0 grains of Winchester 296 gave the second-best accuracy with groups under an inch. LiL’Gun performed well with the Berger Varmint, and 12.5 grains of this powder provided groups that ran .385 inch at 100 yards and resulted in the highest velocity of 2,946 fps. With the other 45-grain bullets, while there were some interesting groups in the 1.25-inch range, the Barnes spitzer solid with 12.5 grains of LiL’Gun hit 2,855 fps with the smallest group of the testing program, at .36 inch. Moving up to 50-grain bullets, the Hornady V-MAX with a charge of 12.0 grains of LiL’Gun provided a velocity of 2,926 fps with the best group of .696 inch.

Using 52-grain bullets, both the Hornady A-MAX hollowpoint and the Speer hollowpoint grouped into 1.25 inches with A-1680 powder, while the last one, a Nosler Ballistic Tip, grouped 1.50 inches with IMR-4227, and although it was not the most accurate, it did have a leg up on velocity. The heaviest bullet tested was the Sierra 55-grain spitzer boat tail that grouped into an inch. The Hornady Spire Point’s group measured .568 inch with a charge of 12.5 grains of LiL’Gun and a velocity of 2,815 fps. After all the testing, there is no doubt that Hodgdon’s LiL’Gun is an excellent powder for the 22 Hornet.

Today, with modern components that deliver minute-of-angle accuracy, and a fine rifle like the Browning 1885 Low Wall, the 22 Hornet is still a great cartridge for taking woodchucks in the north forty. With its mild report and economical handloads, the 22 Hornet will be around for a long, long time.