220 Swift

Loads for a T/C Encore Handgun

feature By: Aaron Carter | April, 18

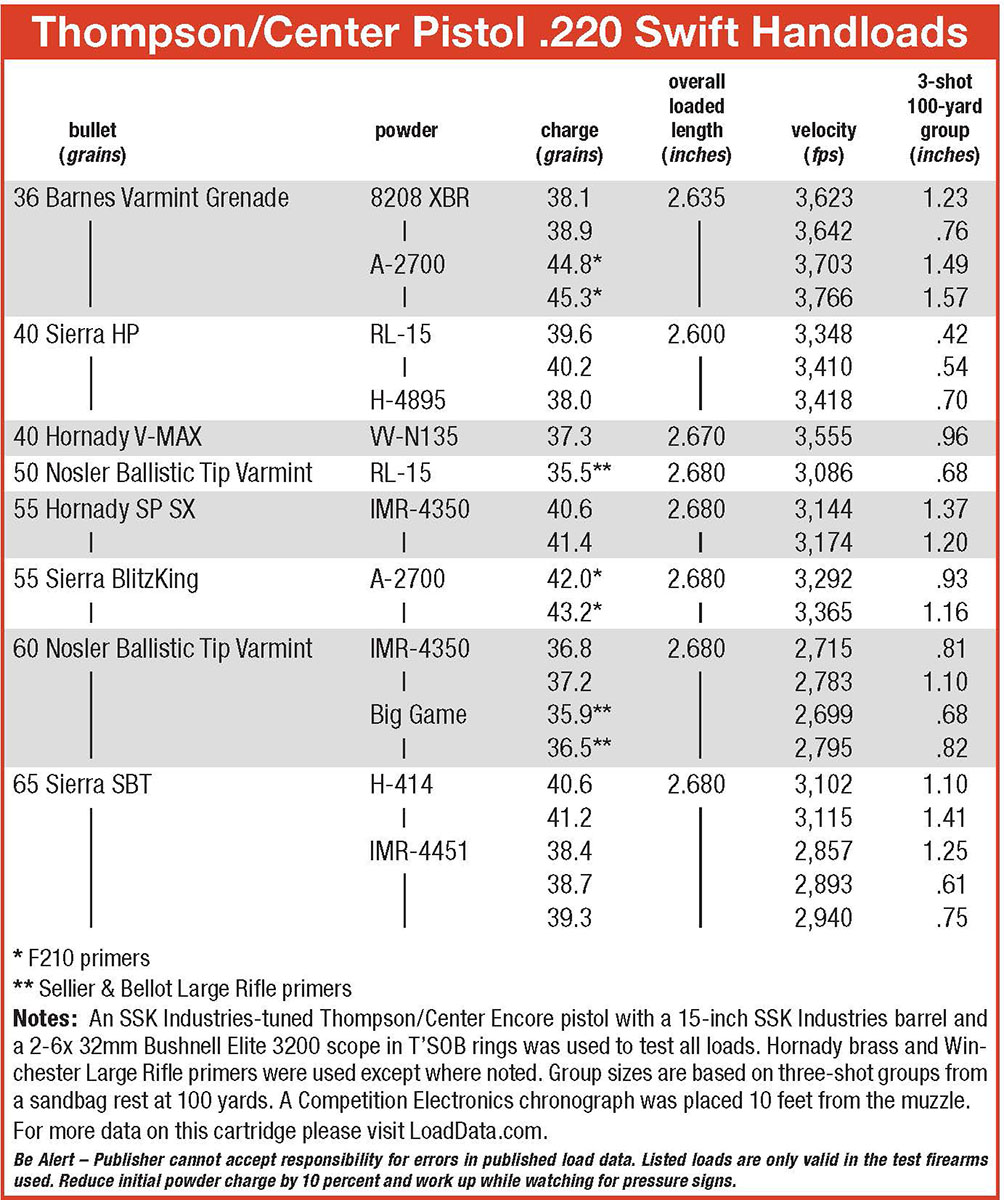

The truth is, the 220 Swift does what it was designed to do, and it does so extremely well. True to its name, the Swift is all about velocity; its forte is launching .22-caliber varmint bullets extremely fast, thereby resulting in flatter trajectories. With a faster time to target, deflection from wind is lessened, too – no small concern on small, distant prairie dogs and ground squirrels. Moreover, the additional velocity increases the bullet’s on-target energy, which is beneficial on larger predators. Its chief rival, the 22-250 Remington can do much of what it can, though increased case capacity – about 5 to 6 grains – gives the 220 Swift a slight edge.

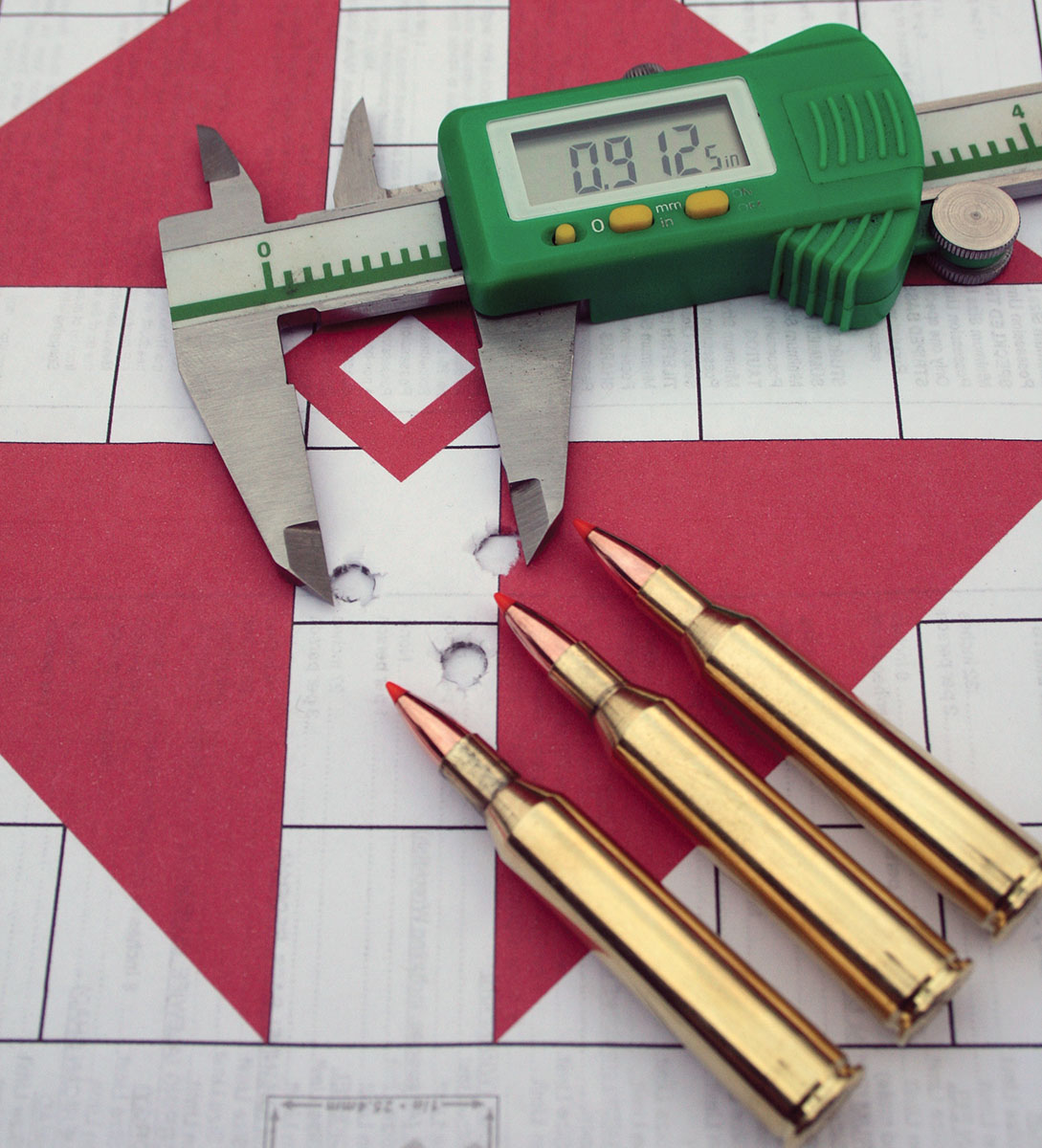

Given its pedigree as a long-range varminting and predator round, it might seem unusual to chamber a handgun in 220 Swift, but that’s exactly what I own: an SSK Industries-tuned Thompson/Center Encore pistol fitted with a custom, 15-inch SSK barrel and a 2-6x 32mm Bushnell Elite 3200 scope in three T’SOB rings. As a semi-rimmed cartridge, the Swift is a natural for single-shot handguns, and recoil in the heavy Encore is fairly mild.

Inhibited from reaching its full potential in a 15-inch barrel, the 220 Swift is still quite potent nevertheless. In fact, across the spectrum of .22-caliber bullets, the above-mentioned T/C produces external ballistics slightly better than those of a 223 Remington with a 24-inch barrel. This makes the cartridge/handgun combination an excellent option for mid- to long-range varminting – easy-to-carry platform, no less. The Encore accompanies me on hunts for predators (teamed with a shotgun), groundhogs and spring gobblers (we’re allowed to use rifle cartridges in Virginia). Long beards that hang up just outside of shotgun range don’t get a free pass with the Encore on hand. Lastly, it’s a nice companion to a like-chambered rifle.

While some aspects of handloading the 220 Swift for a handgun are similar to those for rifles, there are some unique considerations.

Weighing 10 cases revealed an average weight of 174 grains, with the variance being .9 grain. Preparation was minimal, and case life was surprisingly long. Perhaps owing to the precise chamber, minimal brass upkeep was needed during the testing process; case length increased only minutely even after repeated firings, and the primer pockets remained tight. As such, the per-shot cost of each case was relatively small. MidwayUSA sells Hornady 220 Swift brass for around 74 cents each, and Norma brass runs about 20 cents more. Depending on the brand, that’s almost double the cost of some 22-250 Remington brass, so it does pay to take care of it.

Bullets

Bullet-wise, 220 Swift factory ammunition is pitifully limited. Most ammunition is loaded with 50- or 55-grain bullets, though Federal currently offers a single Nosler 40-grain Ballistic Tip load. For someone who lives (or hunts) in a lead-free zone, they are simply out of luck; there are no factory lead-free options. Handloading is thus required to meet the varied needs of 220 Swift users – especially handgunners.

One of the drawbacks of the 220 Swift is that factory barrels typically have a 1:14 rate of twist, or 1:12 – both handle most varmint bullets from 36 to 60 grains relatively well.

Eschewing tradition, J.D. Jones, owner of SSK Industries, uses a 1:9 twist in his barrels. The result is the ability to use a greater variety of bullets on the heavy end; in fact, I was able to get stabilization (and good accuracy) with Sierra’s 65-grain SBT bullets that require a 1:10 twist. Some bullets that purportedly stabilize in a 1:9 twist didn’t perform acceptably, so experimentation is required.

Since velocities from the 15-inch barrel of the Encore run about 500 to 700 fps slower than those typical of a 24- or 26-inch barrel, most varmint bullets will work – including those with velocity thresholds often exceeded from a 220 Swift rifle. Examples include the fragile Hornady 50- and 55-grain SP SX bullets. In most cases, velocities from a 220 Swift handgun will mimic those of a 223 Remington or 22 PPC rifle and will best those of a 223 Remington handgun with a 14-inch barrel by 200 to 500 fps. The largest gains are with heavy bullets.

To counteract velocity loss, one option is to select a bullet that is lighter in weight than the one you often use. For example, dropping down from a 55- to 50-grain (or even 40) V-MAX or Ballistic Tip Varmint will boost velocity, though lightweight (and thus less streamlined) projectiles generally exhibit lower ballistic coefficients (BC). For shots out to 300 yards, this is of minimal concern. Selecting a bullet of lighter weight but reasonable BC is the best solution, but be careful that it will stabilize with your barrel’s rate of twist.

When choosing a projectile, also take into consideration the quarry and anticipated shot distance. Lighter projectiles lose velocity rapidly, and with that comes a loss in energy, too. Though starting slower, bullets such as the 60-grain Ballistic Tip Varmint shed velocity at a slower rate and pack more energy when striking game. With higher BCs, they’re also less susceptible to wind deflection, though this is splitting hairs.

Concerning leadless bullets, unless using a fast-twist barrel, choose one of the lightweight bullets. Good choices included the Nosler 35-grain Ballistic Tip Lead Free, Barnes 36-grain Varmint Grenade, Speer 30-grain TNT Green HP, Lehigh Defense 38-grain Controlled Fracturing bullet or Speer’s 43-grain TNT Varmint Green. If your 220 Swift has a 1:12 twist, there’s also a Lehigh Defense 45-grain Controlled Chaos bullet.

Powder

There’s no shortage of propellants suitable for use in the 220 Swift, but due to the pistol’s abbreviated barrel, it is prudent to select propellants with slightly faster burn rates. These will not be listed in loading manuals as producing the highest velocities. Slower-burning propellants – those shown with scorching velocities – need longer barrel lengths to reach peak performance. Need proof? Look at the accompanying table: When paired with the Sierra 65-grain SBT, statistically speaking, Hodgdon H-414 showed virtually no increase in velocity when the propellant charge was increased by .6 grain. With the case nearly fully, it was incapable of using the extra propellant.

Choose a powder from the faster-burning options. Some of the best selections for the 220 Swift include IMR-8208 XBR, H-4895, Varget, Vihtavuori N135 and Reloder 15. That’s not to say that stalwarts such as IMR-4350, A-2700, H-414 and Big Game aren’t suitable. Some of my best groups were produced using these propellants.

Another consideration in selecting a propellant is temperature stability. Consider this: By using a shorter barrel, you’re already at a velocity disadvantage, so why worry about the propellant losing even more velocity with a change in ambient temperature. New propellants, such as Hodgdon’s Extreme series and IMR’s new 4451 and 4166 are not only temperature insensitive, meaning velocity will change minimally throughout the year (or when traveling), but the latter options also have an ingredient to help eliminate copper fouling. IMR-4451 not only produced good velocities with the heavy Sierra 65-grain SBT bullets, but it provided good accuracy, too.

Lastly, when loading for a handgun do not start at the midpoint and move up too fast because, as previously mentioned, you might find that you are simply wasting propellant for little to no gain.

Primers

When working up loads, I generally use primers recommended by the bullet and/or propellant manufacturer; however, a variety of large rifle primers were used for the accompanying loads. Of course, as is standard procedure, reduce the load by 5 percent when changing primers and work up slowly, watching for signs of pressure. Primers used include the Federal 210, Winchester Large Rifle (WLR) and Sellier & Bellot. S&B primers continued to belie their cost of $20 per thousand. Note that some of the smallest groups were produced using these primers, and there were no failures.

Like the 22-250 Remington, 220 Swift brass benefits from neck sizing only after the initial firing, and full-length sizing is really only needed if chambering becomes difficult; however, that should be less of an issue in the T/C Encore. For this article, RCBS full-length sizing dies were used and case life was good. Other than that, assembling 220 Swift loads is straightforward.

While some 220 Swift shooters recommend downloading it slightly to preserve barrel life, doing so counteracts the reason to own one – to drive .22-caliber bullets really fast.

Barrel life can be extended by allowing the barrel to cool (good luck in midsummer) between strings and cleaning. While I attempt to let the barrel fully cool, doing so is not always possible. The reality is, however, that barrels are expendable – time is not. Remove two forend screws and the pivot pin, and the Encore is easily outfitted with a new barrel. So the barrel wear concern is, in my view, a moot point.

Like other handguns, it’s imperative to rest an Encore on the frame – not the barrel – and provide a slow, consistent trigger pull with every shot. Even small inconsistencies are revealed as large mistakes at distance when shooting a handgun. One thing I do is practice with an air pistol, which is cheap and quiet to use.

As loud as it is from a rifle, the 220 Swift is more so from a handgun. Other shooters at the range quickly take note. Double up on your hearing protection. Recoil isn’t objectionable, especially considering the performance that you’re getting from a handgun.

If you’re looking to purchase a handgun for varmint and predator hunting, you won’t go wrong in choosing the 220 Swift. It’ll do everything you need . . . and then some.