Twists & Turns

Exploring Barrel Twist Rates for .224-Inch Bullets

feature By: Mike Thomas | April, 18

While the long established “slow” .22-caliber twist rates of 1:12 or 1:14 are capable of providing excellent accuracy with light bullets, such twist rates are much too slow for even minimal accuracy expectations with modern heavyweight bullets. For these, twist rates of 1:7 to 1:9 are required. The faster twists generally offer a versatility unobtainable with the slow twist rates in that they can be the basis for fine accuracy not only with the modern, heavy bullets, but also with many of the lightweights.

When I ventured into AR-15s for the first time a few years ago, I worked with three Colts, all with 1:7 barrels. I didn’t intend to load light bullets for these rifles, but as a matter of interest, tried bullets as light as the Sierra 53-grain MatchKing. Surprisingly, accuracy was very good, as it also was with varmint bullets of 55 grains.

It seems that interest in the older 22s with slow twist rate barrels has diminished. Regardless of the advantages of fast twist bores, there are still many 22 centerfire rifles with 1:12 and 1:14 barrels. In the shooting spectrum, fads come and go. Trends change and will continue to do so. The shooting world may have gone through phases with moly-coated bullets and cryogenically treated barrels, but 22 barrels with a fast twist rate are here to stay because the advantages are quantifiably real.

That certainly doesn’t mean slow twist barrels are hopelessly obsolete, even if they are often ignored these days. I’ve never seen performance or accuracy lacking when using a good 50- or 55-grain varmint bullet in a centerfire 22 bolt action for taking shots at coyotes a few hundred yards distant. Many other shooters are in the same category, and the described setup is used by them with complete satisfaction. However, when ranges exceed 300 yards, my favorite bullets begin to quickly loose steam that is retained by the heavyweights.

Conversely, consider a 50-grain bullet with a BC of 220 fired at a muzzle velocity of 3,300 fps in comparison to a 65-grain bullet with a BC of .300 that has a muzzle velocity of 3,000 fps. Both are fired from a 223 Remington rifle with a 22-inch barrel. For varmint use, 400 yards is a very long range for most users of the 223 cartridge. Downrange trajectory favors a heavier bullet with a higher BC by about .5 inch – an inconsequential figure.

The current BC fixation by many shooters is often a wasted effort. Of course, wind drift with a 65-grain bullet will be less, but how many shooters are capable of reliable wind doping? There is certainly a valid argument in favor of decreased wind drift; even a small advantage remains an advantage and does not diminish. This is particularly true for shooters that can “read” wind.

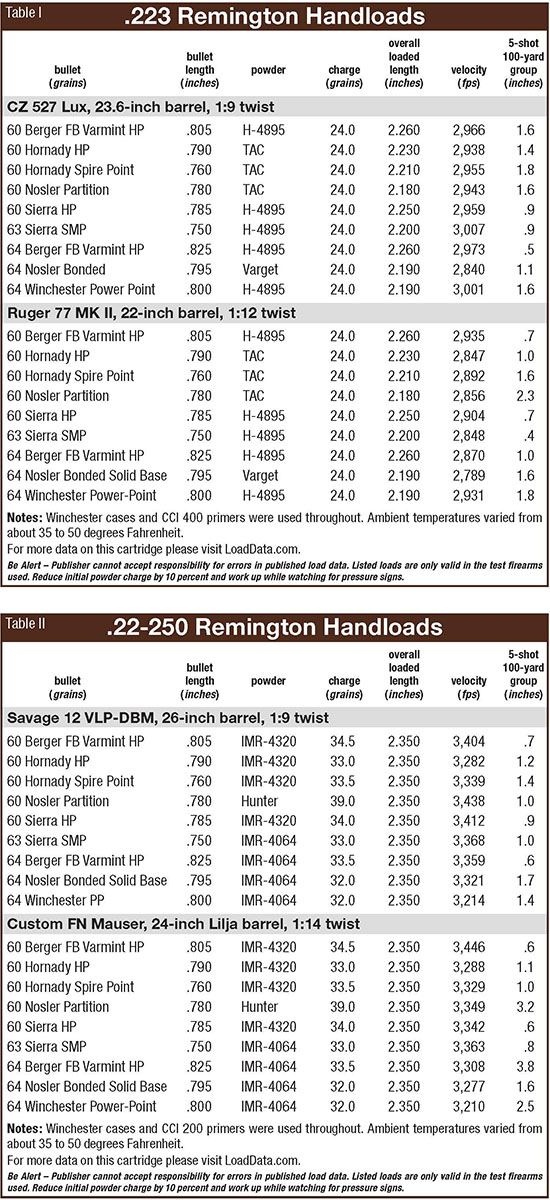

Used in this project were two rifles I’ve owned for more than 25 years. A Ruger M77 MK II 223 Remington has the original 22-inch Ruger barrel with a 1:12 twist. This rifle is equipped with a Leupold FX-II 6x36mm fixed-power scope in Ruger rings. An FN Mauser 22-250 Remington is on its second barrel, a 24-inch stainless Lilja with a 1:14 twist. The rifle has a 1970’s-era Lyman 6x Silhouette scope in Leupold rings.

Again, the idea here was to find out just how heavy and how long a bullet I could shoot and still get decent accuracy in the older, slow- twist barrels. As a comparison, I used identical loads in the new rifles with their 1:9 twist barrels.

The powders used had been around a while and were well proven for suitability and accuracy for each respective cartridge. Because of ogive shape, some bullets had to be seated to a depth that was below maximum recommended overall length for the 223 Remington cartridge.

When working with the Colt ARs, I found that with all the bullets tried, seating them just a hair below the maximum recommended overall length of 2.260 inches (to assure reliable magazine loading and feeding) worked well, and accuracy was very good; this was not in line with what I had been accustomed to with bolt-action rifles. With one of the ARs, I did experiment with seating bullets more deeply and found no accuracy advantage. As for the 22-250 rifles, all bullets were seated to the maximum recommended overall length for the cartridge, 2.350 inches.

Winchester brass was used for both cartridges. CCI 400 Small Rifle primers were used for the the 223, and CCI 200 Large Rifle primers were used for 22-250 loads. While it’s not always possible with a particular bullet/powder combination, I prefer to stay with load data that can be verified in a published loading manual.

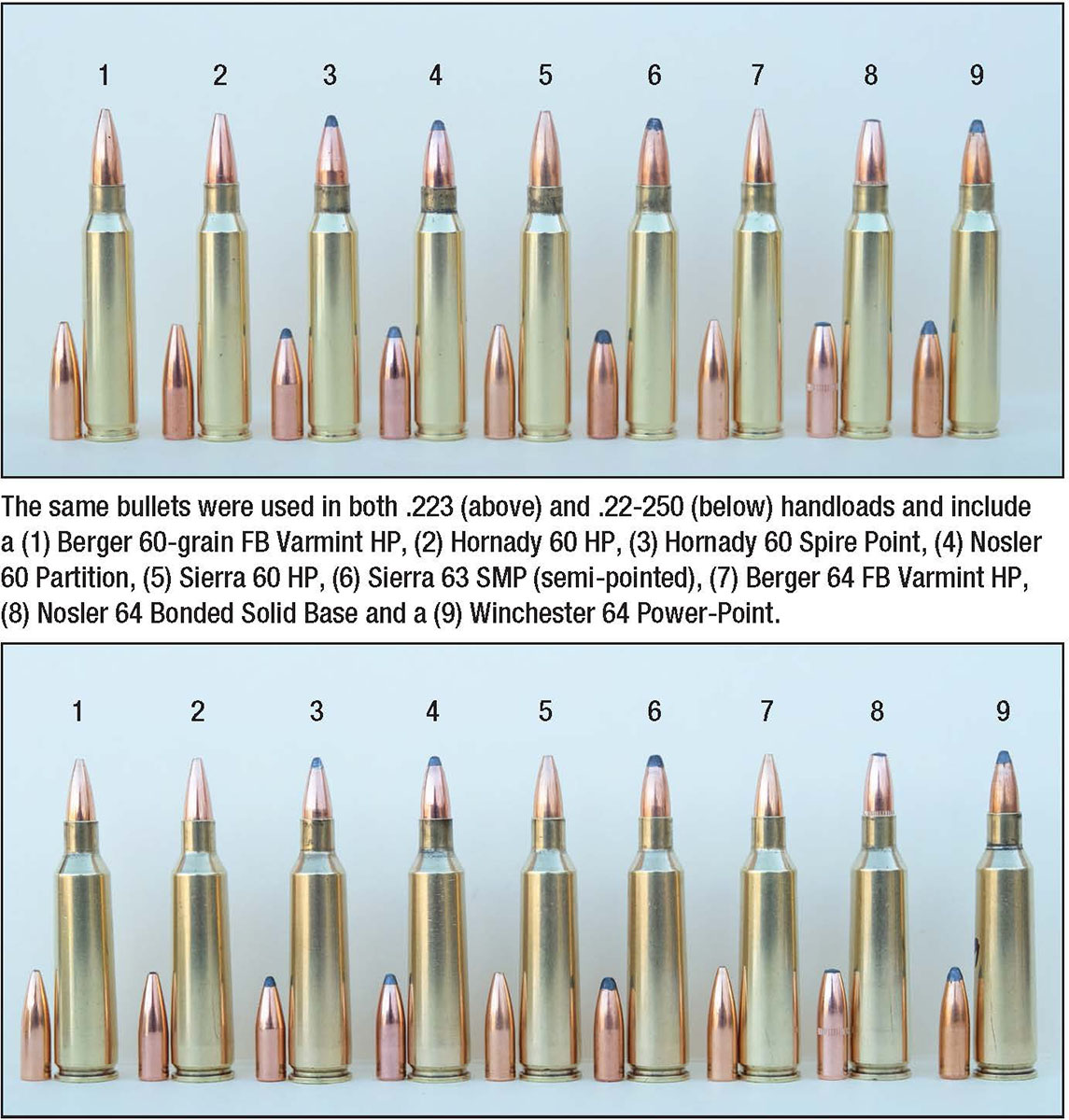

Nine bullets were used in the 60- to 64-grain range. Most are within the maximum weight and length capabilities of older slow-twist barrels. A few, like both of the Bergers, are recommended for barrels with twist rates of 1:12 or faster. The bullets can be found in the accompanying table, including each bullet’s length.

The two slow-twist rifles, the Ruger and the FN Mauser, had well-established accuracy histories with various 50- to 55-grain bullets not included in the evaluation here. The CZ and the Savage were new, and it was necessary to determine their accuracy potential before giving credence to the handload group sizes depicted in the data tables. Both rifles proved capable of .5-inch accuracy using the Sierra 65-grain GameKing SBT bullet, my favorite AR bullet. It will consistently equal the accuracy of the Sierra 69-grain MatchKing (regular, nontipped version), but I have not made a long-range comparison where the MatchKing would likely show an advantage. Sierra recommends a twist rate of at least 1:10 for the 65-grain GameKing. It measures .860 inch in length.

Reviewing the tables, some important conclusions can be drawn. The original purpose of this endeavor was to determine the maximum weight and length of suitable bullets for use in .22-caliber barrels with 1:12 and 1:14 twist rates.

Considering that all rifles were capable of very good accuracy, many of the bullets used were not the best accuracy pick for the individual rifles. This was anticipated from the beginning, but there were some exceptions as noted in the tables.

A cursory glance at group sizes shown in the 223 Remington table would indicate groups from the 1:9 barrel of the CZ and the 1:12 barrel of the Ruger are fairly close overall. Actually, the CZ groups averaged 1.27 inches, and the Ruger 1.23 inches – virtually the same.

This project was of a very narrow span from the beginning, but necessarily so because the subject matter is seldom dealt with in a comprehensive manner. As such, it touched upon some unlikely comparisons. For those with a serious interest in pursuing similar experiments with personal rifles, perhaps this report may serve as a rough guideline.