6mm Remington

Long Range Rockchuck Loads

feature By: Patrick Meitin | April, 18

Fast forward thirty-some years and you find my father and me addressing distant Idaho rockchucks (yellow-bellied marmots). We have a requisite 223 Remington (a customized Savage Model 10 with a McMillan A-2 stock), Mossberg’s MVP Varmint 204 Ruger and a deadly-accurate, custom ’98 Mauser 22-250 Remington that we find all lacking.

Rockchucks emerge from adjacent wheat, descending into granite on the opposite canyon rim as the late-May days turn warmish. They’re all 425 to 475 yards away. That isn’t the issue; the real problem is a light wind. A 5- to 7-mph waft wreaks havoc – more frustrating when including inconsistent velocity. I’ve been twisting the turrets of my 22-250’s Vortex Golden Eagle 15-60x 52mm scope every which way, connecting, at best, on one shot in seven – and here we’re discussing 5- to 10-pound rockchucks, not dainty ground squirrels.

As the day grows hot and the wind begins to carry grit, we pack up, contemplating Wyoming prairie dogs well south. During the drive we mulled over our morning’s performance, agreeing a repeat engagement is warranted – including an armament update. My father solved the problem with a Ruger Precision Rifle 6mm Creedmoor with 1:7.7-inch rifling to accommodate high-ballistic coefficient (BC) bullets. With tailored handloads it prints .5-inch groups – at 200 yards.

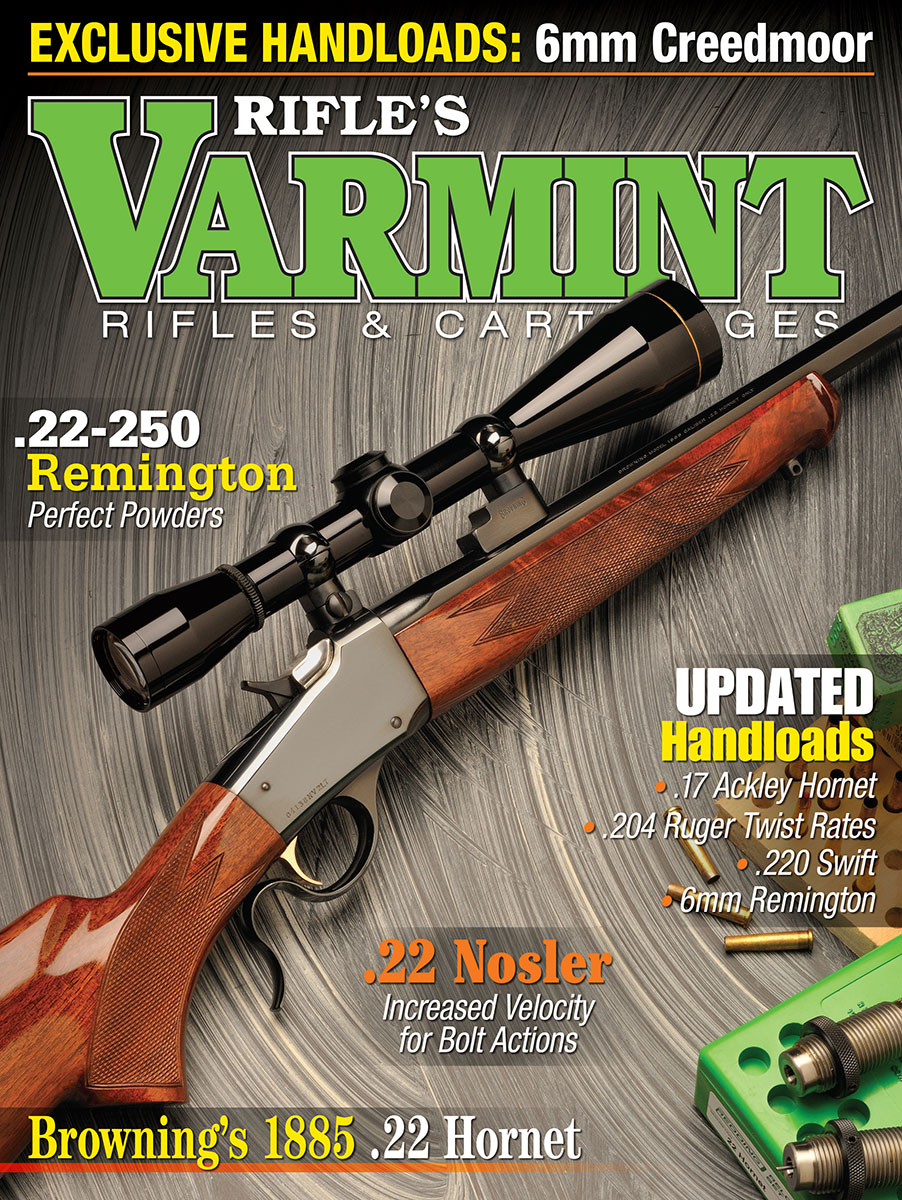

Plan “B” included converting a Remington 700 ADL 25-06 to 6mm Remington (the long action would allow seating long-for-caliber bullets properly) with a fluted 24-inch, 1:9 twist Wilson barrel ordered from Ragged Hole Barrels, a Timney trigger, AccuFab muzzle break (Jim Stanton: 208-846-6142) and some gunsmithing by Ronnie Soderquist at Cherokee Firearms Repair in Spanaway, Washington.

Atop this rifle is a TRUGLO Eminus 16 4-16x 44mm scope set in Leupold STD rings on a one-piece base. This tactical-style scope includes locking target turrets, a super-fine TacPlex Reticle, stacked side focus/lighted reticle knobs and a 30mm tube for increased erector adjustment. The extended throw lever and spring-loaded flip caps are nice touches, and the glass is super sharp and bright.

Of the common 6mm cartridges, the 6mm Remington – originally 244 Remington – has languished in relative obscurity. It retains dedicated fans, but it just didn’t stick in the bigger picture. The 244 Remington, essentially a necked-down 257 Roberts with its shoulder angle increased about 5 degrees (similar to RCBS founder Fred Huntington’s 243 Rockchucker) was released in 1955, the same year Winchester introduced its3243. Introductory 1:12 twist rifling regulated rifles to bullets weighing no more than, say, 90 grains at the time, marking them as dedicated varmint rifles – all well and good. The 6mm loaded with 55- to 85-grain bullets is a serious zinger and deadly effective on varmints to 350 yards – farther on calm days. It is generally accepted that rifles labeled “244 Remington” (typically Remington’s Model 722), include 1:12 twist barrels; while those stamped “6mm Remington” automatically include a 1:9 twist. The later statement is universally true. The 244 label could be considered inconclusive. Supposedly, some .244-stamped barrels had already transitioned to a twist rate of 1:9, so it’s worth investigating an individual rifle’s twist before dismissing them.

Winchester’s introductory 243s included 1:10 twist, allowing stabilization of heavier bullets and serving double duty for big game. By 1963 Remington realized it had misread the situation and rebranded the 244 in newly introduced Model 700 rifles, including the 6mm Remington and faster 1:9 rifling. This allowed the 6mm Remington to do anything the 243 Winchester would, and a bit more, but it was too late. The 243 blasted off as the 6mm began circling the drain.

But even 1:9 rifling remains questionable – at least in relation to 6mm bullets, owning the highest possible BCs and fitting long-range aspirations. To my mind, BCs touching .450 represent a solid long-range benchmark. Research reveals that getting there with 1:9 rifling is fairly certain. I first wondered if this was even necessary. The plan was to address rockchucks at 400 to 500 yards; not 1,000-plus-yard steel gongs. Still, recalling that Idaho wind, I was curious to see how far BC can be pushed and at what point accuracy deteriorates in direct relation.

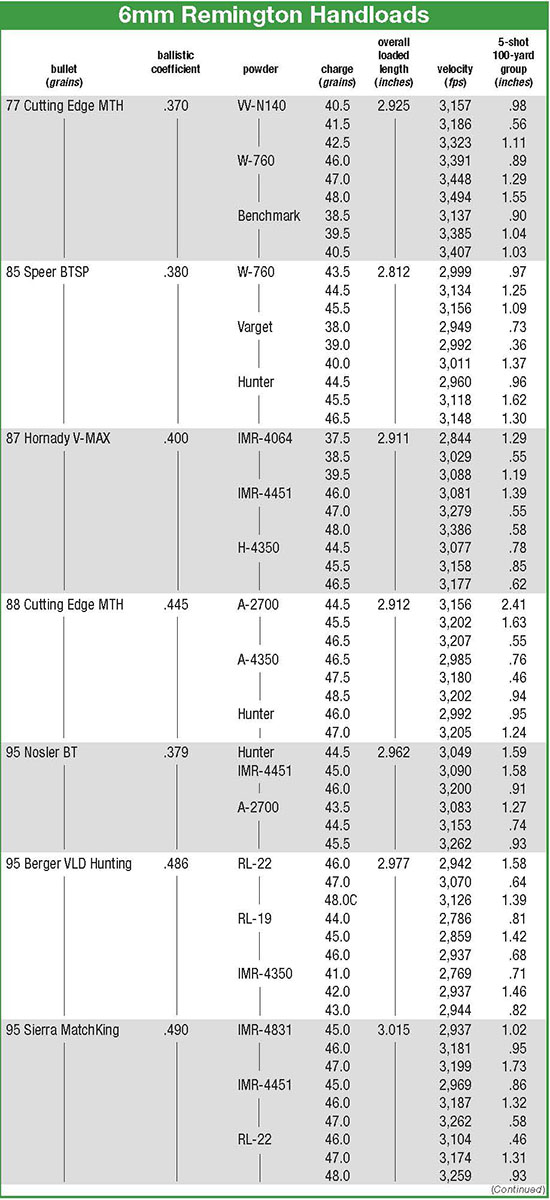

Handloading began with 6mm bullets in the 77- to 88-grain range (BCs from .370 to .380) and moved toward 100-grain or heavier projectiles with BCs well above the long-range maximum. Alliant, IMR, Hodgdon and Western powders were selected for maximum efficiency. Two hundred Hornady cases were secured. Hornady cases hold 54.3 grains of water (essentially the same as Federal and Remington brass), in contrast to 56.1 grains held by vintage WW-Super cases pulled from my piecemeal collection. Sample bullets from Barnes, Berger, Cutting Edge, Hornady, Nosler, Sierra and Speer were assembled with Olive’s Gun Shop in Orofino, Idaho, filling gaps by donating bullets. RCBS full-length dies were used, and were likely the same vintage as the cartridge itself. Powder charges were weighed on an RCBS beam scale. Federal 210 Large Rifle primers were used exclusively.

Up front, the goal was maximum velocity combined with maximum accuracy. That’s an admission, but also a caution – approach maximum loads with care, as even related starting loads are right of middle, though all were acquired from published data. As a dedicated long-range rockchuck shooter, I was looking to minimize wind drift by minimizing flight time. It is also generally accepted that stabilizing long-for-caliber bullets with minimal rifling twist is mitigated – if only slightly – by boosting velocity. It’s also safe to say reliable stabilization established at 3,200 feet above sea level during cold winter months (where and when loads were developed) will only improve after moving 3,000-plus feet higher during warmer spring months. This focus on velocity admittedly destroys accuracy with many powders, with starting loads regularly printing the tightest groups.

Facing the task of loading/shooting more than 720 rounds, and anticipating encountering a stabilization wall with the heaviest bullets, trimming the herd seemed reasonable. Three-shot test groups were assembled, seating the highest-BC bullets atop a variety of powders with powder charges pulled from the middle of the listed charge weights. It was both disappointing and thrilling to find everything from Hornady’s 103-grain ELD-X to 108-grain ELD Match bullets punching round holes with promising groups – some exceptional.

Vihtavuori N140, Varget, Accurate 4350 and IMR-4451 powders showed promise with lighter bullets. Highlights included 41.5 grains of N140 beneath Cutting Edge’s 77-grain MTH (.56-inch group); 39.0 grains of Varget pushing Speer’s 85-grain BTSP (.36-inch) and 47.5 grains of A-4350 combined with Cutting Edge’s 88-grain MTH (.46-inch). IMR-4451 accounted for many impressive groups with light bullets, interestingly clustering more tightly as loads approached maximum. IMR-4064 also showed promise, including a .55-inch group with 38.5 grains under Hornady 87-grain V- MAX bullets.

With bullets weighing 95 to 100 grains, Alliant Reloder 19 and 22 worked well. RL-22 resulted in the tightest groups with Berger’s 95-grain VLD Hunting and Sierra’s 95-grain MatchKing. RL-19 provided remarkable groups smaller than .25-inch with Speer’s 100-grain BTSP (43- and 44-grain) loads.

Having earlier mentioned that all bullets punched round holes, indicating adequate stabilization, Hornady’s 103-grain ELD-X provided frustrations during group testing. I added three additional loads attempting to find balance, all with uninspiring results, with just two loads printing just less than an inch. I’m left to assume they just aren’t fully stabilizing. My rifle (and its twist rate) simply didn’t shoot them well. Seating-depth experimentation is in order, however, as other high-BC bullets grouped exceptionally well. Overall, the heaviest bullets proved noticeably more finicky, though certainly capable of remarkable accuracy when the right powder combination was hit upon.

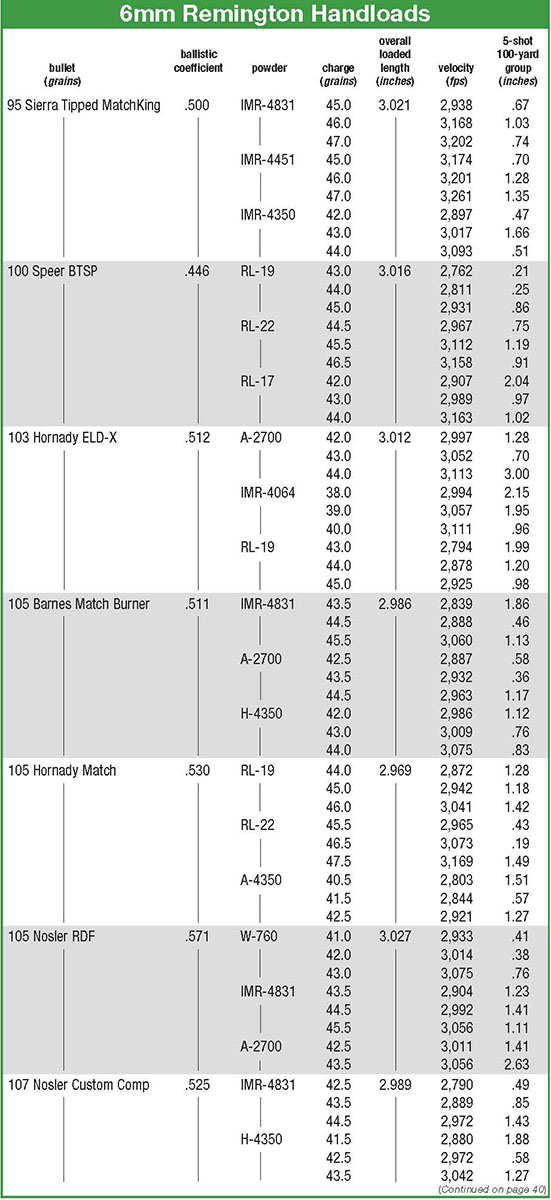

Surpassing the 100-grain mark, 43.5 grains of Accurate 2700 provided a group smaller than .5-inch with Barnes’ 105-grain Match Burner. Reloder 19 and 22 held up with bullets in the 105- to 107-grain class, with RL-19 producing the best groups with Hornady’s 103-grain ELD-X and 108-grain ELD-Match bullets – both just less than an inch. The test’s best group came with 45.5 to 46.5 grains of RL-22 beneath Hornady’s 105-grain Match bullet. The first group was so tight (.19-inch) I labelled it a fluke and shot the load again. The second group measured .22-inch – close enough to show the first was no accident.

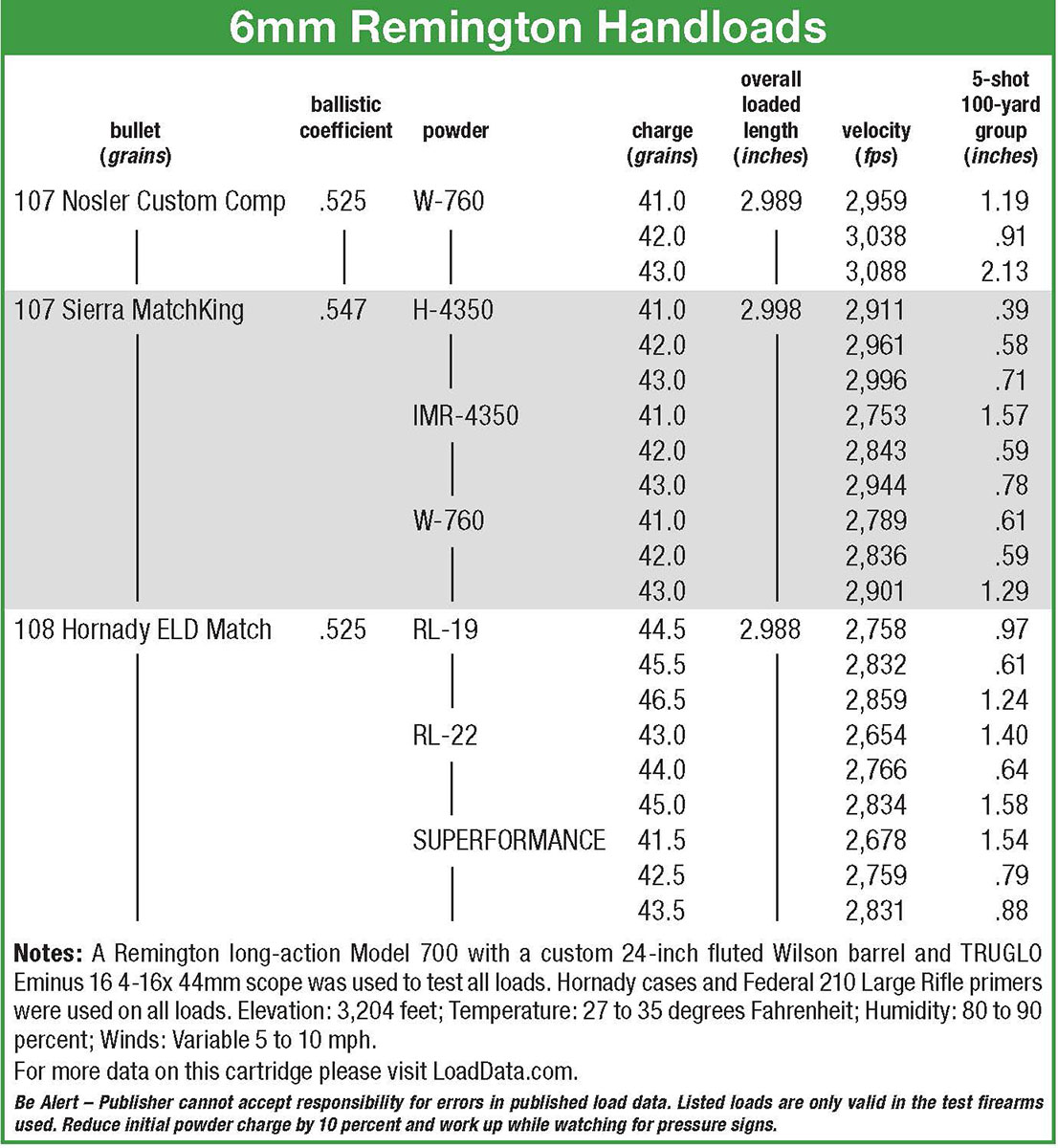

Whereas W-760 proved disappointing with lighter bullets, it redeemed itself with heavier bullets, posting not only some of the tightest groups (down to .38 inch with Nosler’s 105-grain RDF), but impressively low extreme velocity spreads. H-4350 also offered impressive accuracy with heavier projectiles, particularly with a Sierra 107-grain MatchKing (.39 inch) and Nosler 107-grain Custom Competition (.49 inch). Versatile IMR-4831 held its own with heavy bullets; 42.5 grains beneath a Nosler’s 107-grain Custom Competition provided a .75-inch group. With Hornady’s 108 ELD Match, RL-22 and Superformance warrant further investigation.

This trial run proved more successful than envisioned, relinquishing a multitude of field-ready loads with bullets meeting or exceeding beginning expectations. I haven’t even begun tweaking minor details. It would seem I’ve fulfilled my beginning goal of building an effective long-range rockchuck rifle. Running the numbers through Hornady’s ballistics calculator, I can look forward to cutting wind drift by more than half in contrast to the standard varmint rifles that were wielded last spring. Rockchucks beware.