223 Remington from 30-30 Winchester?

Multitasking for Varmints

feature By: Art Merrill | April, 22

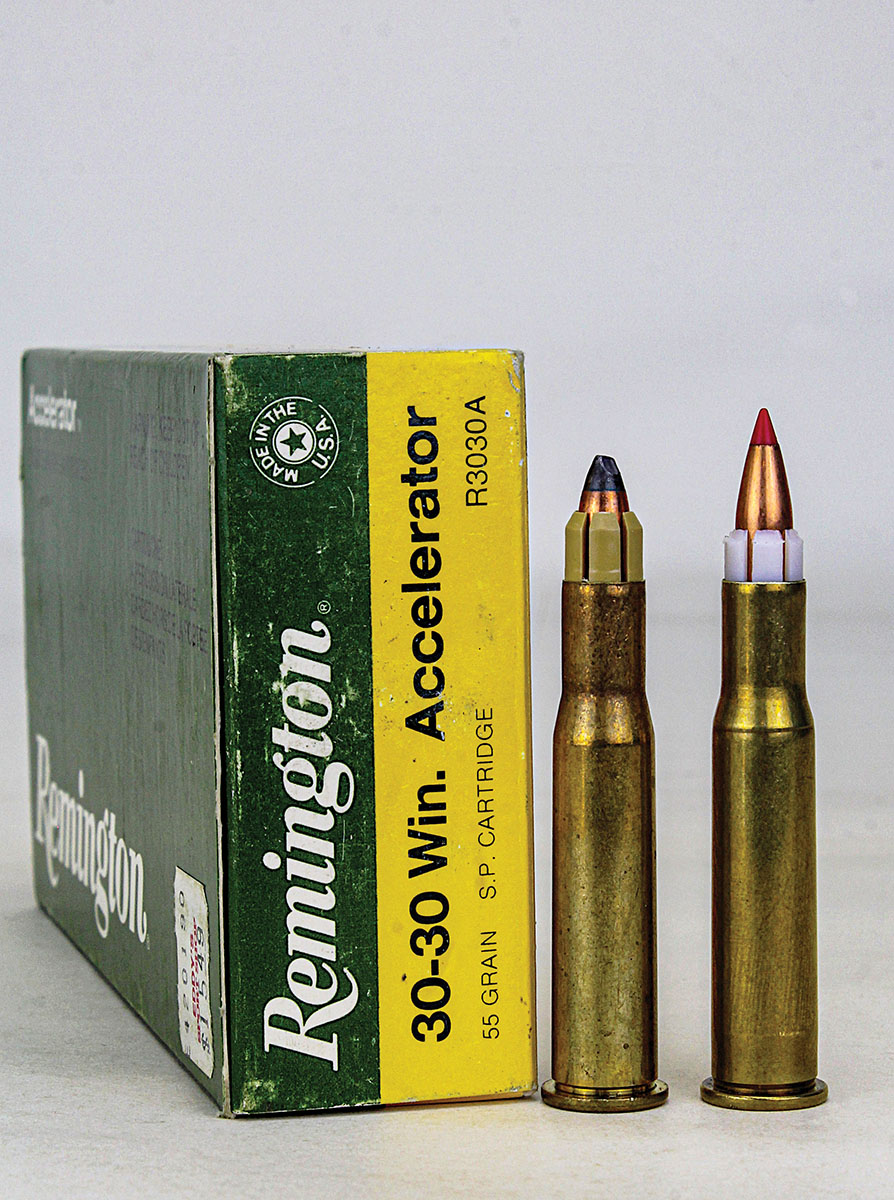

Remington’s aptly named Accelerator added a blistering 600 to 1,000 feet per second (fps) to the aforementioned .30-caliber cartridges compared to its standard-weight bullet loadings. The 30-30 Winchester Accelerator boasted 3,400 fps; the 308 Winchester 3,770 fps; and the 30-06 version broke the 4,000-fps barrier at an advertised 4,080 fps. Those speeds were made possible by the plastic sabot.

Shotgunners know the sabot as the plastic sleeve that encases a bullet. For muzzleloader shooters, a sabot permits firing, for example, modern .45-caliber, jacketed pistol bullets in a .50-caliber rifle. Cartridge rifle shooters and handloaders are perhaps less familiar with the sabot.

The sabot (a French word for a wooden shoe and pronounced, “sĕ – BŌ”) concept goes back at least 200 years, when the French utilized it in 1824 to fire newfangled explosive shells from a naval canon. That sabot was made of wood, accounting for its name, though other materials, such as plastics, soft metals and carbon fiber are used in making modern sabots.

Today, military forces use discarding sabots, mostly for arms larger than rifles, for defeating armor, which the projectile achieves in part via exceptionally high velocity thanks to the sabot. The physics are easy to understand since force is equal to pressure times area, the larger the base area of a projectile, the more net force propellant gases can exert on it. The sabot is a force multiplier, providing a temporary larger area for gases to push a smaller-than-bore-size projectile.

Sabots launching subcaliber bullets offer an intriguing juxtaposition of both .30-caliber and .22-caliber ballistics within a single cartridge, and something we must immediately consider is rifling twist rate. Twist rates for 30-30 Winchester rifles is typically 1:10 or 1:12 to stabilize 150-grain and 170-grain .30-caliber bullets, a twist rate generally considered too slow to stabilize .224-inch bullets weighing much beyond 55 grains. As example, AR-15s chambered for 223 Remington or 5.56 NATO cartridges routinely feature twist rates of 1:9 or 1:8 for launching bullets of 69 to 75 grains, while heavyweight 80- and 90-grain bullets do better with a 1:7 or 1:6.5 twist rate. At the light end, bolt-action varmint rifles chambered for223 Remington occasionally have a 1:14 twist to stabilize bullets of 52 grains and less.

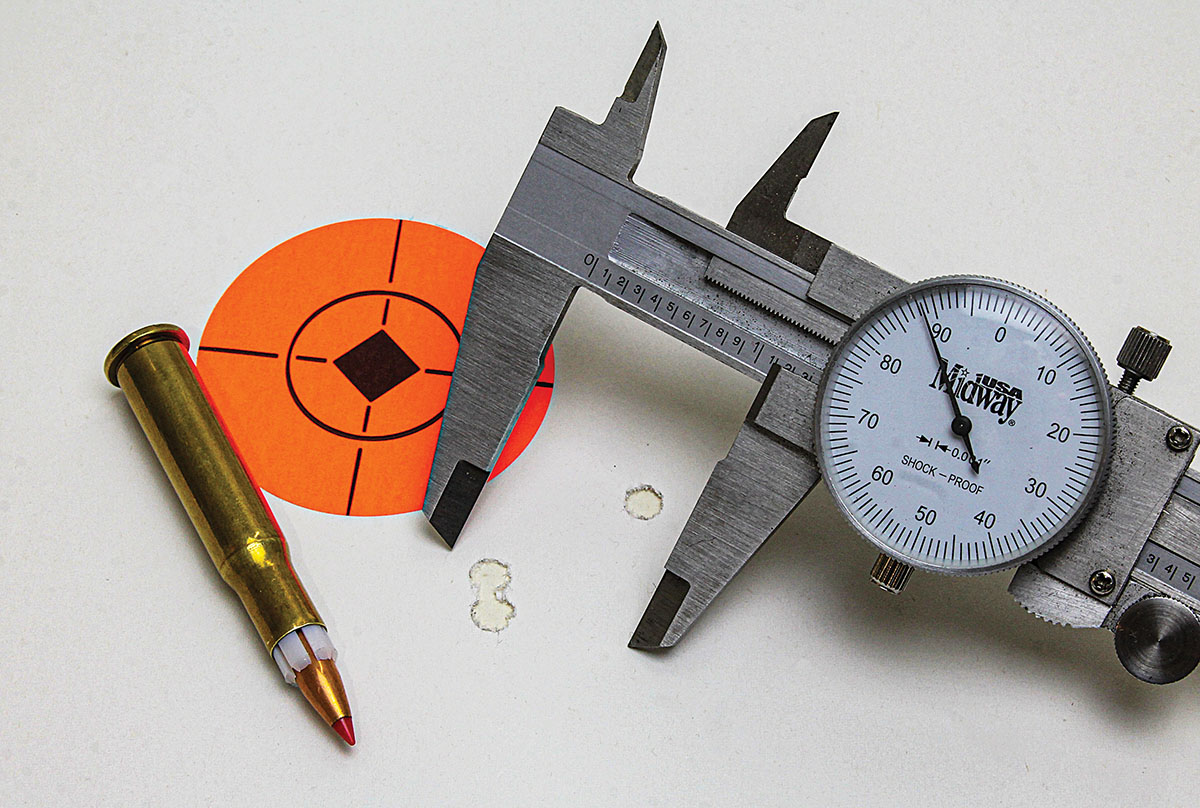

The bolt-action Savage Model 340B used here has a 1:12 twist. The rifle, made sometime between 1950 and 1967, included a period Weaver K2.5 scope in an original mount. Savage also chambered the Model 340 in three varmint calibers, 22 Hornet, 222 Remington and 223 Remington, so it seemed reasonable to expect suitable varmint accuracy from the rifle, if not from the 30-30 Winchester cartridge itself.

Thirty-caliber sabots and tools for loading them are available from E. Arthur Brown Company (eabco.net) at a very reasonable cost. A starter kit that includes 100 sabots and a plastic bullet seater die is $29.95; a separate Lee Universal Case Expanding Die is available for $16.95. The expander die is necessary to open up case mouths a bit to easily accept the plastic sabot. Making the seater die of plastic seems odd, but it’s a cost-saver and is adequate for the light duty it performs.

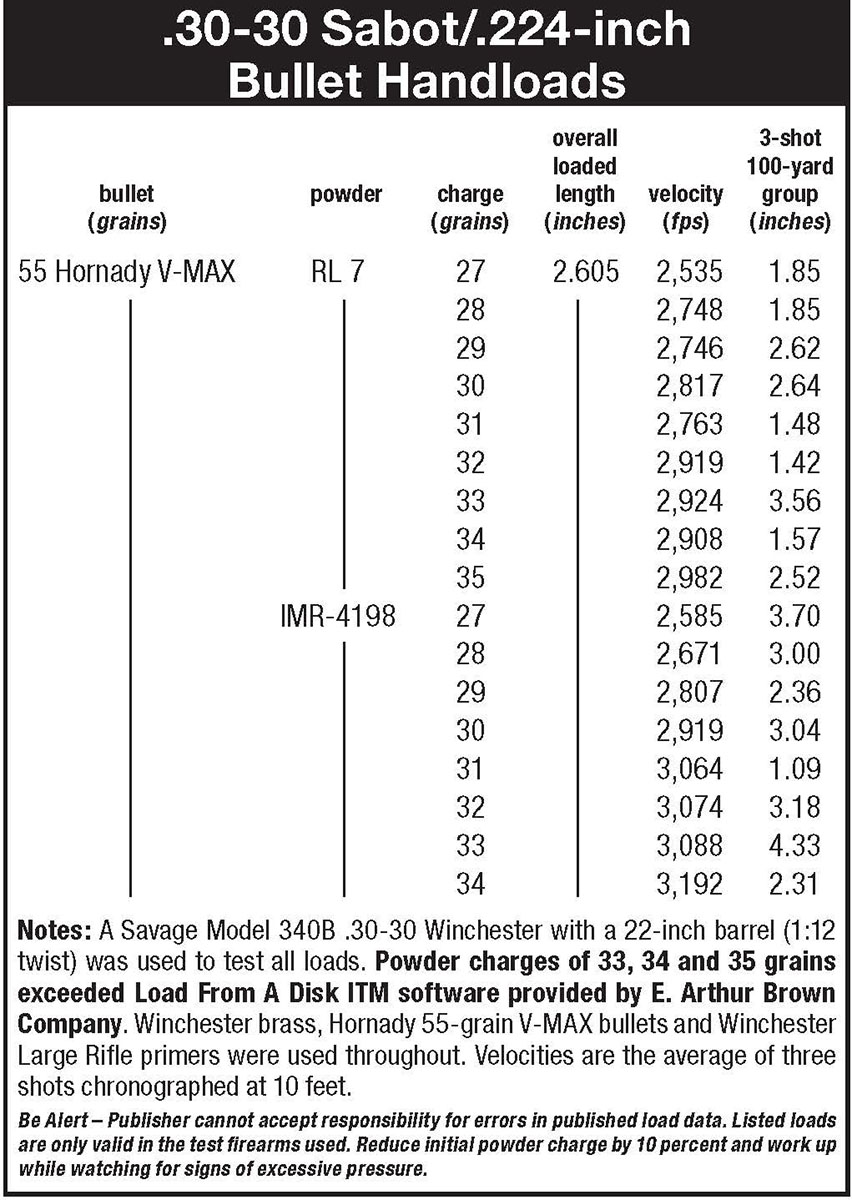

Happily, E. Arthur Brown Company also provides some get-started load data along with the sabots, though it was derived from Load From A Disk I software in 1993 and not actually real-world tested. It lists the same maximum charge – 32.2 grains – for three powders and a 55-grain bullet at a calculated 40,300 psi and recommends a starting charge of about 27 grains. The listed powders are IMR-4198, RX7 and S-4197. “RX7” is Reloder 7, which appears on Hodgdon’s chart of powder burn rate two steps from IMR-4198. “S-4197” is likely Scott 4197, which is rather obscure and no longer listed. IMR-4198 and Reloder 7 are on the fast end of rifle powders, which makes sense for medium-size rifle cases launching very light bullets – or in this case, very light bullets.

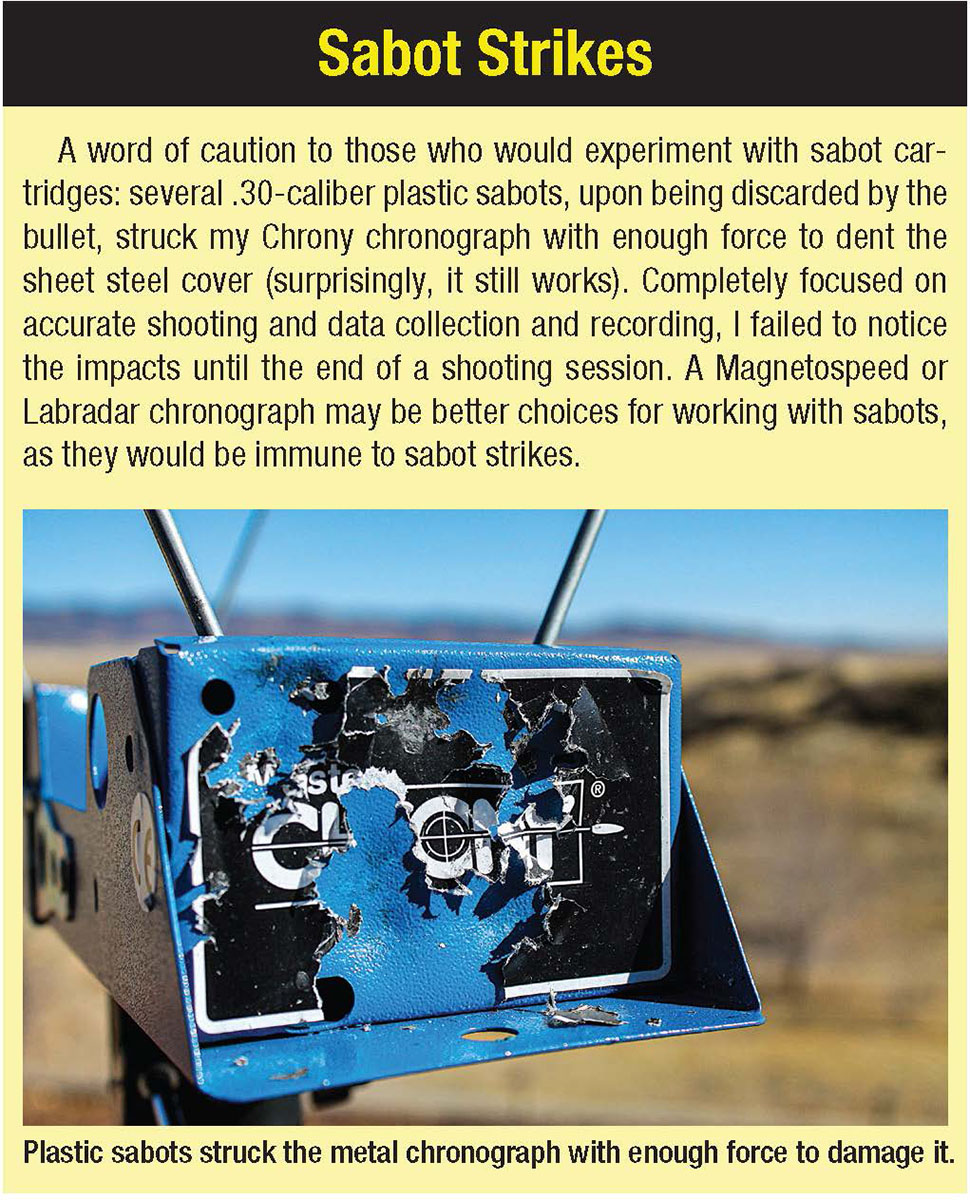

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute publication Velocity and Piezoelectric Transducer Pressure: Centerfire Rifle, revised January 2013, aided me in including the 30-30 Winchester with a sabot and a 55-grain, .224-inch bullet at 3,365 fps. SAAMI’s listing is unsurprising, considering again that Remington offered it as commercial ammunition in its Accelerator line. Importantly, SAAMI erects a signpost for chronographs: at 3,365 fps maximum velocity, it’s probable that pressure is at safe maximum, as well, given 55-grain and lighter bullets. But it’s just a signpost, not an absolute, so during load development it’s critically important to watch not just velocity, but also all the other indicators of increasing pressure, such as stiffened bolt lift, flattened primers and the rest.

Load manuals recommend trim-to lengths of 2.019 to 2.030 inches for 30-30 Winchester. Winchester cases I had on hand for Cowboy Lever Rifle Silhouette competition were already trimmed to 2.026 inches, plus they had received my “thousand-yard treatment” – beveled flash holes and uniformed primer pockets – so I utilized them as is. All case mouths received a bevel, and a Lyman .30 caliber M Die expanded case mouths slightly to prevent damaging the sabots.

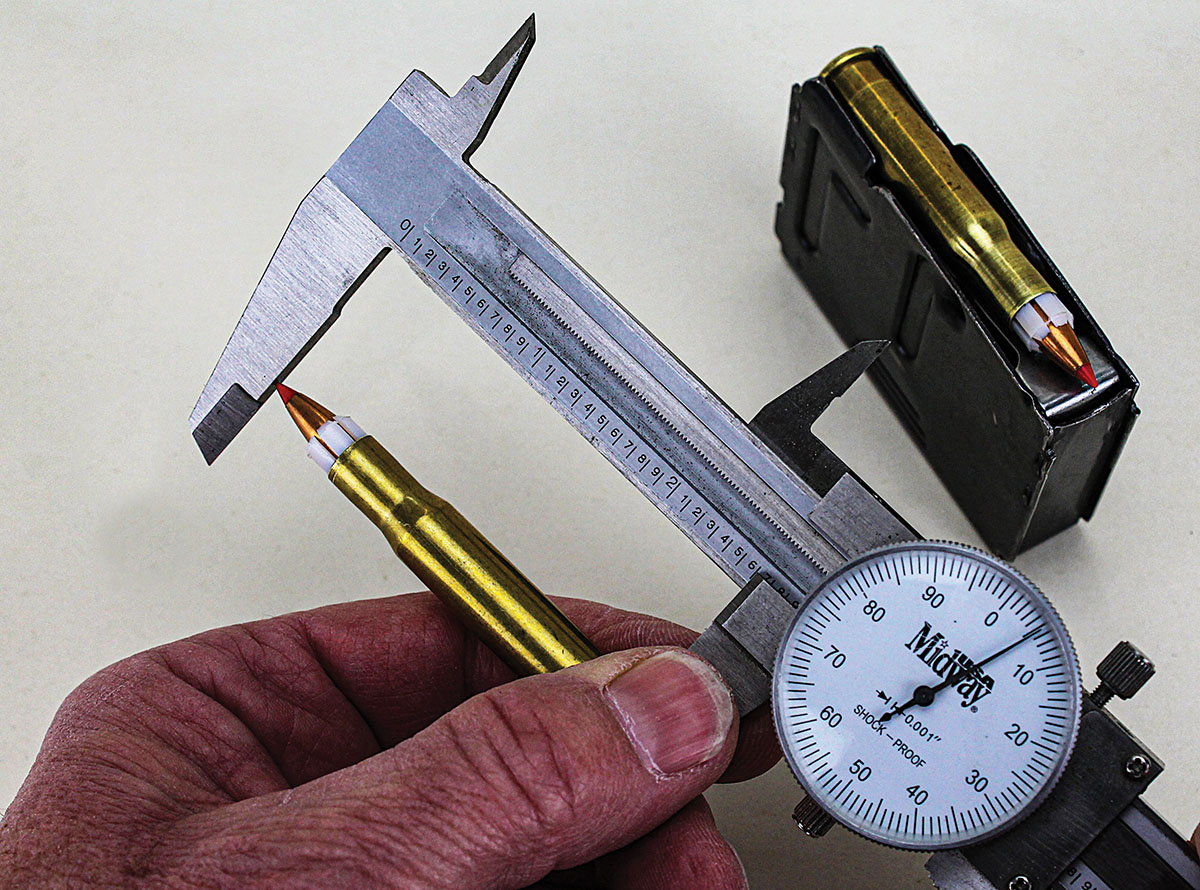

At first, it seemed that bullets could be hand-seated in the sabots, but the plastic bullet seater was necessary to force the bullet the last fraction of an inch to seat fully to the bottom of the sabot. The sabot holder fits in the press where the shellholder would normally be; made of plastic or nylon, the fit of the sabot holder in the press was extremely tight, requiring the use of pliers to install and remove. No instructions accompanied the seating die, but adjustment and operation are intuitive to the experienced handloader: hand seat a bullet in a sabot, place the sabot on the holder and run the ram up to its stop. Screw the seater down until it contacts the bullet, then continue screwing it in by increments while try-fitting the seating depth until you feel the bullet has bottomed out in the sabot.

Seating the bulleted sabot in a case is done the usual way, with a standard seating die. Overall length of the 30-30 Winchester cartridge is given as 2.550 inches; cartridges loaded to an overall length of 2.605 inches with Hornady’s 55-grain V-MAX bullet were just barely short enough to feed through the Savage 340B’s box magazine. Given the plastic of the sabot, I elected to apply a light-moderate crimp so as not to damage it, but enough to keep the sabot from migrating out of the case during handling and cycling from the rifle magazine. Note that the case mouth crimps only the sabot and not the bullet. Crimping is a commitment, as a kinetic bullet puller will pull the bullet, but not the sabot.

Combining E. Arthur Brown Company’s .30-caliber sabot kit and powder recommendations with the 30-30 Winchester and the Savage 340B did not produce stellar groups, with only one load approaching a 1-inch group, but it did prove the viability of handloading sabots. It’s a good bet that lighter bullets and a 1:10 twist in a modern rifle would do better, and there’s a nearly unlimited combination of powders and bullets with which to experiment.

Internet rumors claim the Accelerator line disappeared due to political pressure, the supposition being that a bullet launched via sabot and used for nefarious purposes would bear no rifling marks to forensically prove the weapon of origin. The reality, however, is mundane capitalism: “Low demand over long periods of time caused Remington to discontinue this line of ammo,” Remington Ammunition Marketing Manager Joel Hodgdon told me. Remington phased out Accelerators beginning in the 1990s, and completely stopped manufacture in 2009.

If launching bullets at high velocity via plastic sabots produced consistent superior precision at long range, then it would be loaded in sniper and competition ammunition. It isn’t. A sabot works and potentially offers adequate precision at reasonable distances, but here it did not equal a dedicated varmint rifle/cartridge combination, though it shows promise with, perhaps, lighter bullets and other powders. Its purpose, rather, is to wring a bit of varmint multitasking from a big-game rifle by providing higher velocity and flatter trajectory than any .30-caliber projectile can manage, culminating with varmint-appropriate terminal performance. It appears that with careful load development, it can succeed.