Everybody Loves Velocity

The 4,500-fps WSSM Project

feature By: Jim Matthews | April, 22

The group contained one southerner with a strong accent and an infectious laugh and I was spotting for him. I particularly remember one shot where the ground squirrel cartwheeled high into the air. I quickly found another squirrel and directed him to the target.

He calmly turned back to the riflescope and proceeded to shoot another squirrel. Obviously, he was focused on the task at hand.

If the truth was told (and it would be profoundly politically incorrect to tell the truth), that is one of the key attractions of varmint hunting for small vermin: Seeing their reaction to a high-speed bullet.

This sort of flies in the face of today’s most pernicious rage, namely that we all need to shoot varmints with long, skinny bullets launched out of barrels with fast twists and moderate velocities. Really? How many of us really need a stabilized, high ballistic coefficient (BC) bullet to make those 500-plus-yard shots on varmints?

For example, a 6.5mm Creedmoor with a 143-grain, .625 BC bullet going 2,700 feet per second (fps) at the muzzle will drift a little over 2 inches at 200 yards, and that is computed with a mild, almost unnoticeable 10-mph breeze coming across at about 90 degrees from the barrel. At 300 yards, the drift is more than 5 inches. In real shooting situations, where wind is not only gusting, but is likely different between you and the target, hunters are mostly guessing where to hold even if we have a good wind gauge.

I once hit a ground squirrel at a laser measured 311 yards with a 17 HMR. It took 14 shots! I swear there were some bullet strikes that were feet from the target. Worst of all, when I did luckily center punch it as it sat upright looking around, it ran off to its burrow. A buddy once said, “Our job is to kill these rodents humanely, not torture or maim them. Doing it spectacularly is an added bonus.”

You can shoot at those 600-yard squirrels if you want, but wait and one will pop-up a lot closer and offer an opportunity for a surer shot and more impressive bullet performance.

A highly-frangible bullet (whether it is a soft-lead, thin-jacketed bullet or one of the new lead-free amalgams) doesn’t have to go terribly fast to create spectacular results. However, faster IS better. Let’s be honest, everyone likes screamer cartridges.

Considering all this, my old friend Charlie Merritt decided to build himself a true varmint hunter’s rifle with the Mach IV in mind. After shooting my first California ground squirrel with his gun, I started calling it his “performance queen.” It puts on a spectacular show.

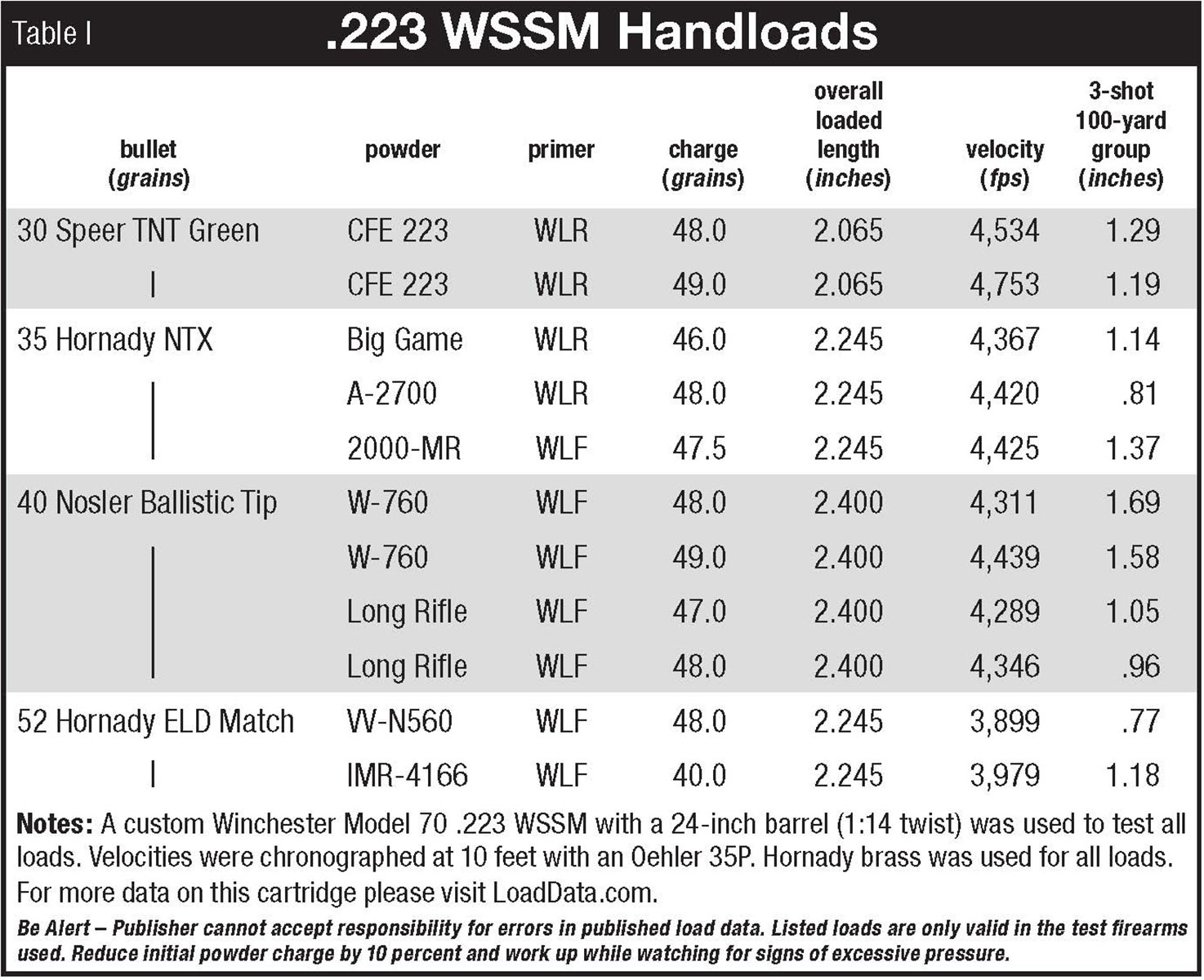

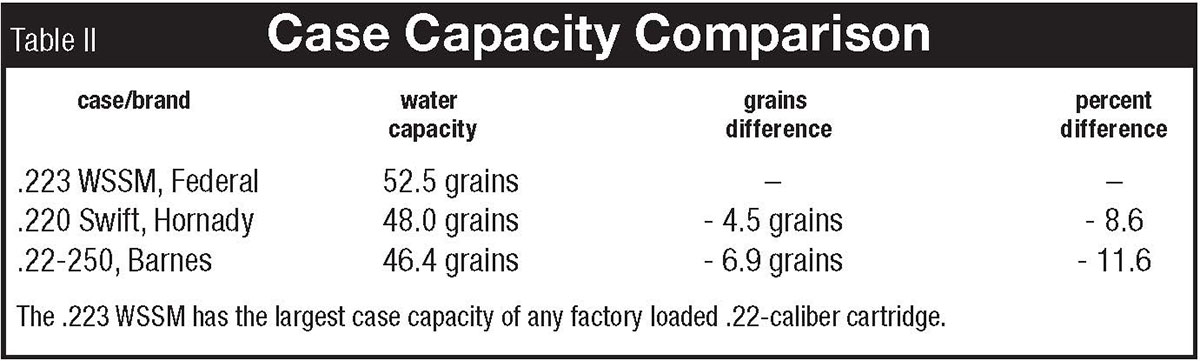

Merritt’s gun is chambered for the 223 Winchester Super Short Magnum (WSSM). Introduced in 2003, the new round was envisioned to be fast, perhaps the fastest .22 ever. It has a greater case capacity than any other factory .22 centerfire on the market (see table I). This is what attracted Merritt to the cartridge. While he didn’t intend to shoot ultra-speed rounds all the time through the rifle, he wanted to have the performance option available for select shots.

Winchester could easily have brought out the 223 WSSM with a 40-grain factory load at 4,350 or 4,400 fps, laying outright claim to the speed championship. Instead, factory loads focused on 55-grain and heavier bullets. It wanted to tap into the interest in shooting heavier (64 grains and up) bullets like those shot in .223 AR-type rifles. There might have also been concern the new round would be saddled with the “barrel burner” moniker, just like the 220 Swift had battled. It didn’t matter that a 22-250 shot with hot loads could burn up a barrel just as quickly. But this was not a common sense discussion.

With the 223 WSSM, it is not too difficult to generate 4,500 fps with some of our lightest bullets on the market. Look at the factory-generated handloading data for this cartridge and you can easily see it reaches that goal. Having no interest in shooting 62-grain, 68-grain, or heavier .22 bullets, Merritt screwed on a 1:14 twist barrel before chambering up the rifle. I shot some discontinued Federal factory loads with 69-grain bullets and they went through the target sideways. Merritt had no intention of shooting anything over 50 or 55 grains through the gun.

There is a conventional thought process that suggests a faster twist barrel will have less velocity than a slower twist barrel. So theoretically, the 1:14 twist would have more velocity than a 1:7 – all other things being equal – because the bullet is grinding against the barrel more as it is spinning. That friction is working against generating more speed, theoretically.

“We have no data to back that up,” said Justin Shrader, a ballistician with Hodgdon powder. Shrader said Hodgdon has done limited testing on this subject. It suggested the impact on speed caused by different twist rates, “is so minute that we can’t perceive it.”

Shrader said they’ve “looked at the issue a little bit because the logical brain says it has to go slower.”

He went on to explain the gun is a complete system with many variables that can impact velocity, from chamber and neck sizes, to throat dimensions, to the brass and components used. In its limited testing, Hodgdon was unable to isolate bullet twist as a factor in velocity. He didn’t say it couldn’t be a factor, but it certainly isn’t a huge one that would be obvious in testing. Merritt went with the 1:14 twist, just in case.

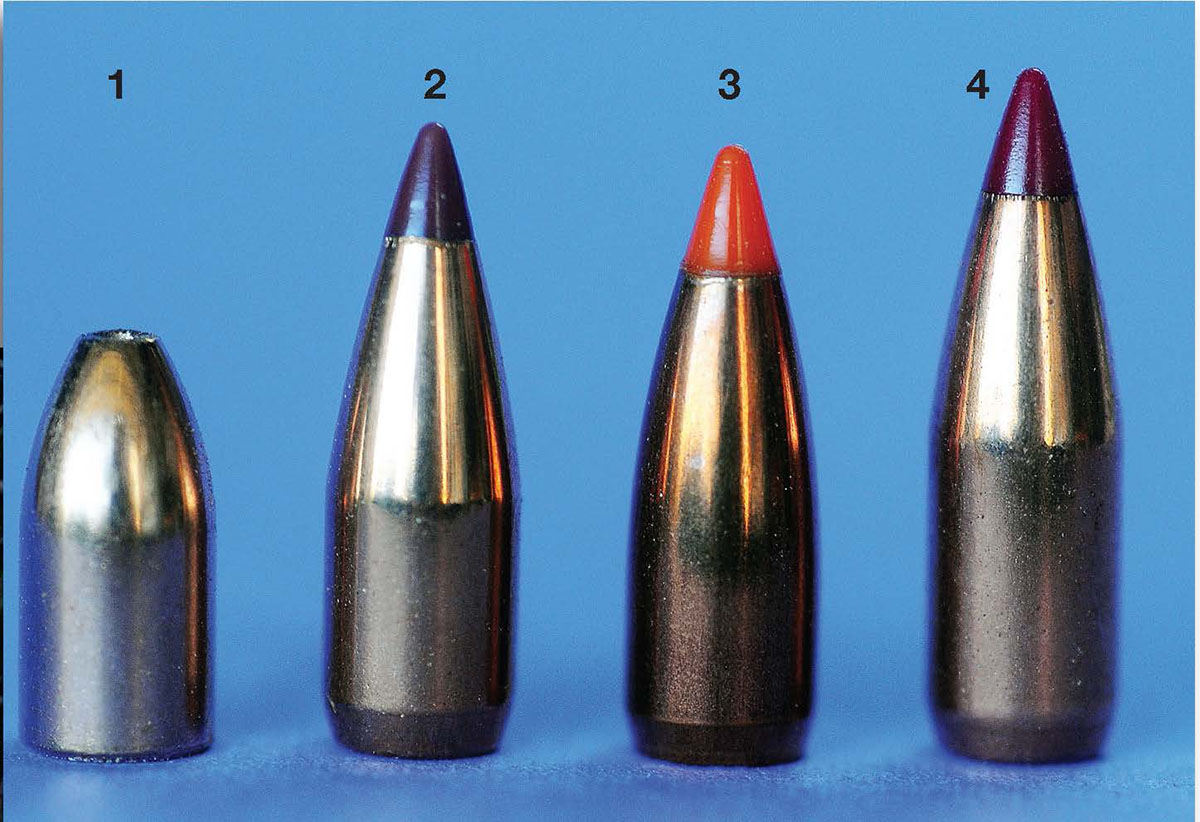

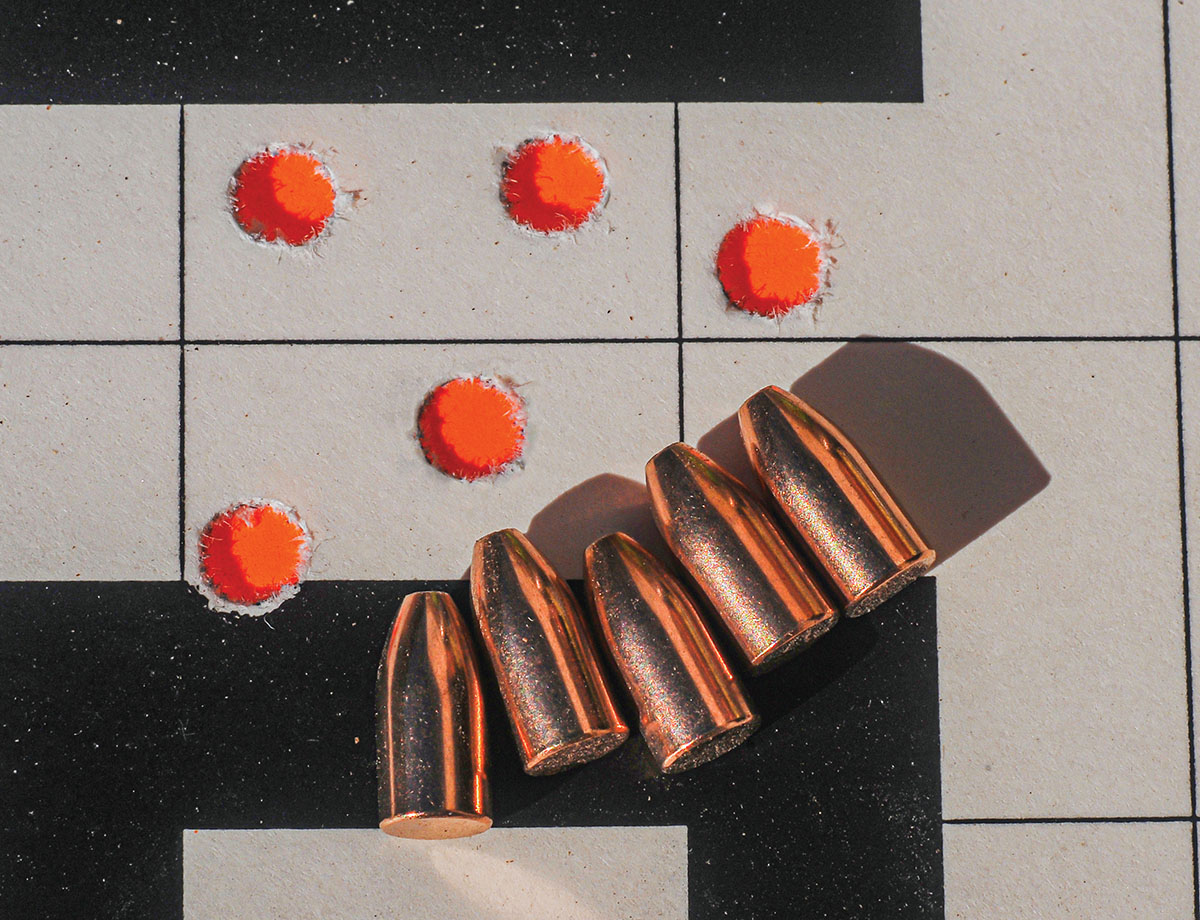

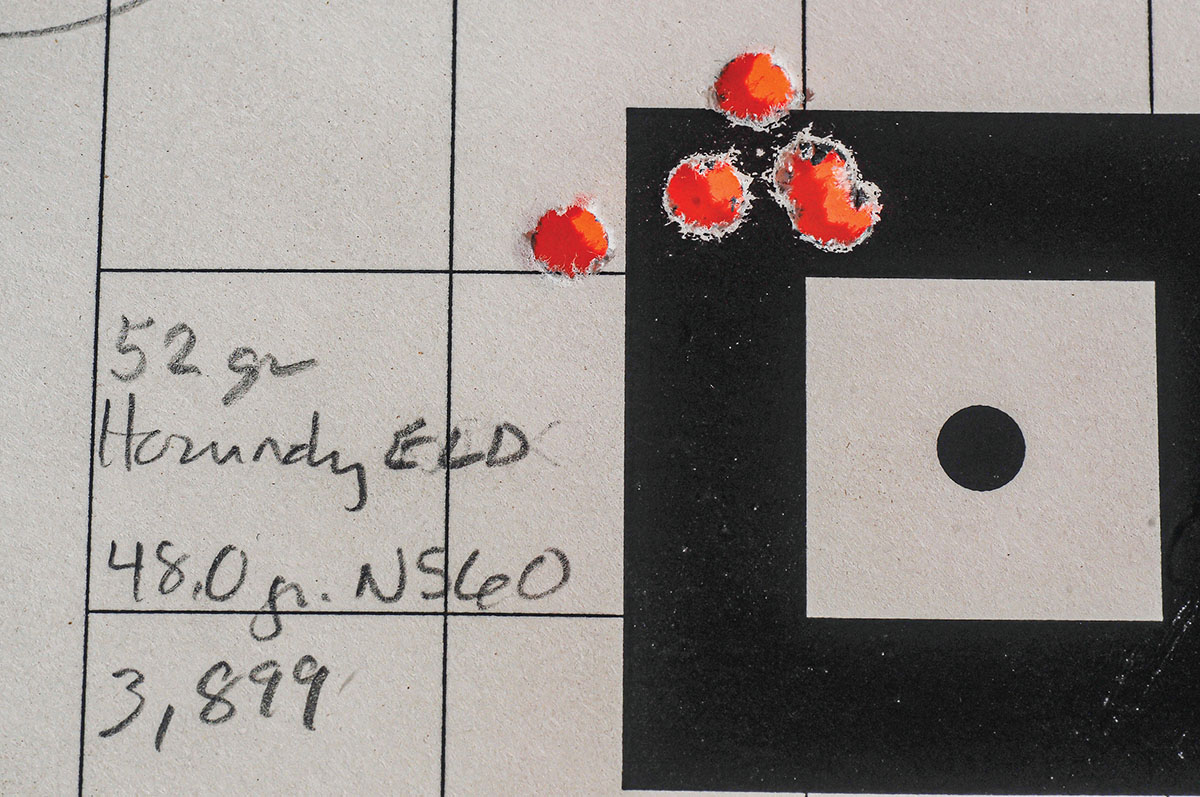

The selected loads in the table with this story all focus on bullets on the light end of the spectrum that work well with a 1:14 twist. They ranged from the Speer 30-grain TNT Green and the Hornady 35-grain NTX bullet, to the 40-grain Nosler Ballistic Tip varmint and up to the Hornady 52-grain ELD-X Match bullet. They were used with seven different powders, including IMR-4166 and CFE 223, Alliant’s 2000-MR, Ramshot’s Big Game and 2700 and Shooter’s World Long Rifle. While all of the loads listed are below the maximums listed by powder manufacturers for these bullet weights, they should all be approached with an abundance of caution. A couple of what I thought would be midrange loads (not shown in the table) based on published data were clearly too hot for this rifle and led to stiff bolt lifts.

It was not a surprise to find the stubby, Speer 30-grain bullet, arguably designed for the 22 Hornet, did not shoot spectacular groups in the test gun. It sure did churn out the speed (and not come apart in transit). I used CFE 223 to try to gin up maximum velocity because Hodgdon’s load data for this powder in the 223 WSSM shows it generated the highest velocity for 35-grain bullets. I didn’t exceed the maximum top load listed for the 35-grain bullet with the test 30-grain load, but the top velocity was 4,700-plus fps.

Merritt’s Mach IV gun was built on a regular Winchester Model 70 short action, not the Super Short action. His 223 WSSM has a “snug” chamber and the 1:14 twist and the barrel is an air-gauged Douglas that is 26-inches long. It features a factory Winchester stock.

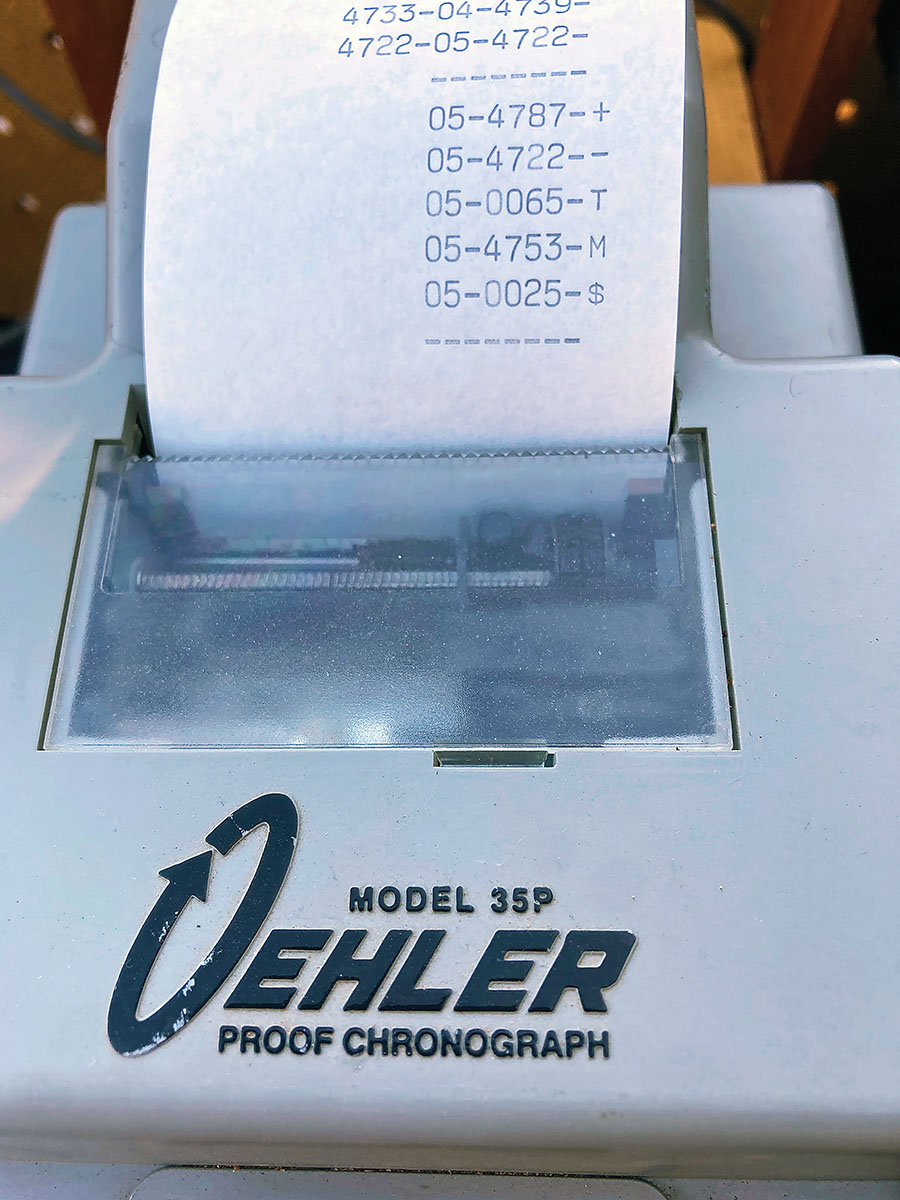

My testing was mostly done during howling winds and groups suffered, but readers can see that some of the loads still shot very well, especially under these conditions. I texted Merritt a photo of the chronograph reading when I was shooting the 30-grain bullets and he immediately called me, chuckling.

Everybody loves a screamer cartridge.