25-06 Remington

A Top Varmint Cartridge Turns 50

feature By: Jim Matthews | April, 19

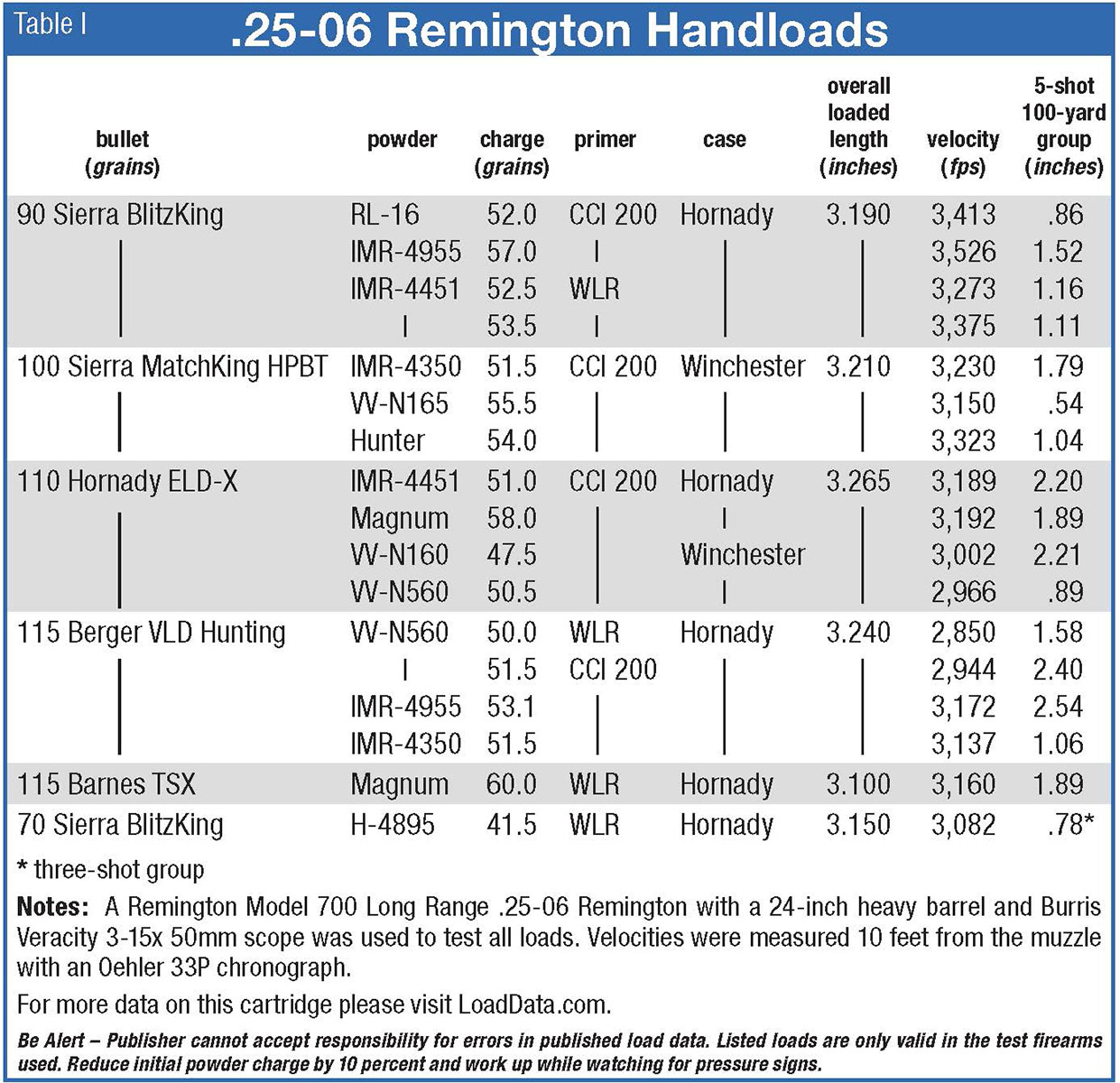

The 25-06 was wildly overbore with the powders available in that era, but Adolph Otto Niedner started chambering the round in 1920 in his rifles, even though it could only achieve about 100 fps more velocity than the 250 Savage. When I was a kid, there were still a lot of old-timers around who called the 25-06 the 25 Niedner. The popularity of the round as a wildcat really didn’t start to take off until the introduction of IMR-4350 powder in 1940. Prior to the introduction of that slower-burning powder, the 25-06 had a middling reputation because it didn’t do much more than the 250 or the far more popular 257 Roberts wildcat round. That was evident even to Remington, which made the 257 Roberts a factory round in 1934 – 35 years before it started chambering the 25-06.

After World War II, and once shooters started using slower powders in the 25-06, its popularity steadily blossomed. Remington became the first company to legitimize a .25-caliber wildcat round based on the full-length 30-06 case, and the 25-06 became instantly popular and remains an enormously popular factory chambering today.

In many ways, it could be considered the predecessor to today’s modern crop of cartridges that shoot long, skinny bullets that seem to slip through the atmosphere to reach distant targets with less drop and wind deflection than the short, stubby varmint bullets shot in most rounds. Throughout most of the 1970s and well into the 1990s, there were always several factory rifles available on the market with varmint-weight barrels from 24 to 26 inches long. Those longer barrels optimized the velocity capabilities of the cartridge, especially with slower-burning powders that make this cartridge shine, and their weight helped dampen barrel vibrations for better accuracy and assisted in steady holds for long shots in the field.

While I’ve had a 25-06 in my gun safe for over 20 years (a Howa Model 1500), I ordered the heavy-barrel Remington Long Range to shoot some of the new bullets to see how they would stack up against the more popular calibers today.

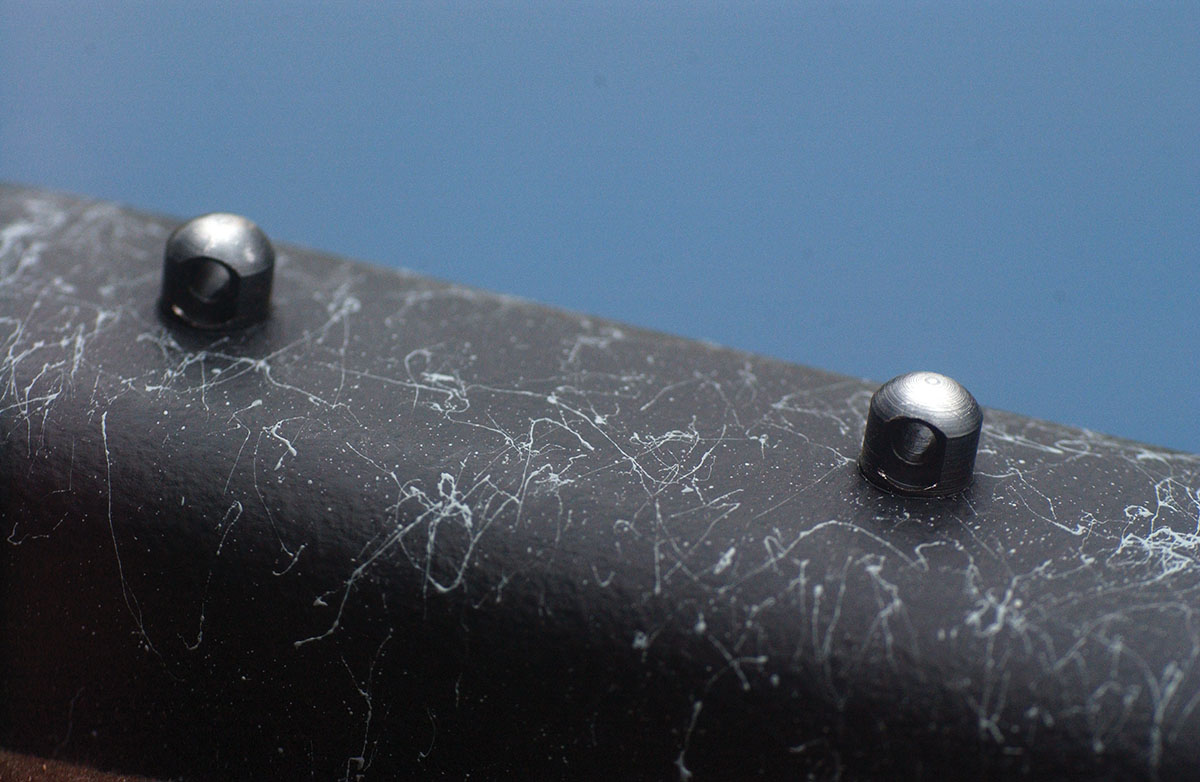

This Model 700 is available only in long-action calibers, including the 25-06, and it comes with a Bell and Carlson M40 tactical stock made of solid urethane combined with aramid, graphite and fiberglass fibers. The stock is black with a gray spiderweb pattern, and it has a cut-out at the front of the relatively-high cheekpiece to facilitate bolt operation and removal for cleaning. The matte black 26-inch barrel and action complement this stock well. The stock also has an aluminum bedding block to enhance the Model 700’s well-documented accuracy. There is an extra swivel stud on the forearm for easy attachment of a bipod, and I fitted the test rifle with a Harris 25C for field shooting.

The trigger is what Remington calls its X-Mark Pro that is easily adjustable for pull weight with a 1⁄8-inch hex key (Allen wrench). The adjustment screw runs through the forward portion of the trigger at its base. The rifle came from the factory set at a very crisp and clean 5.25 pounds (measured on a RCBS spring scale) that felt much lighter. The bolt release, and the magazine release that drops down the hinged floorplate, are also on the inside of the trigger guard, and both are easy to operate with modest finger pressure.

The rifle is not light, weighing a tick over 9 pounds without a scope, and after adding a Burris Veracity 3-15x 50mm scope in Burris Z-Rings and bases, the rifle weighed over 12 pounds with its 26-inch barrel. It has good balance and held well for offhand and sitting field shooting when burning through factory ammunition to get fireformed brass for handloading.

It’s not a revelation that a heavy-barrel Remington 700 can shoot small groups, but from my makeshift tailgate “bench rest,” one of the first groups I shot with the rifle while sighting it in was a three-shot, .665-inch cluster with some old Winchester 90-grain Positive Expanding Point (PEP) factory loads. Behind the target stand was a sloping hillside covered with rocks out to the small peak over 500 yards away, and I proceeded to bust up fist-sized hunks of lava rock out to more than 400 yards.

For my old Howa 25-06, I had long ago settled on two reloads for hunting, including a full-power load with Barnes 115-grain Triple-Shocks at 3,150 fps for big game and a Sierra 70-grain bullet with a light load of H-4895 that moved the bullet just 3,050 fps for varmints. Editors always whine when I include reduced-power loads in my stories and load tables, but they serve a vital function for varmint hunters – in this case allowing for high-volume shooting when in ground squirrel or prairie dog colonies without having excessive barrel heating. There are a lot of young hunters who still have a single rifle for their hunting and press it into service for various tasks until multiple rifles can be afforded. Then there are old, lazy hunters like me who find it simpler to use the same gun for multiple tasks on some trips. The Howa’s big-game load (which can serve double duty as a long-range varmint load) was dialed in to hit 3 inches high at 100 yards, making it dead-on at about 275 yards and only about a foot low at 400 yards. The light load hits 2 inches lower with the same scope setting, making it perfect for volume shooting on those 75- to 150-yard ground squirrels I like to shoot.

The new 25-06 Remington Long Range would serve a different task, and the load table with this story illustrates I was seeking the velocity that would allow for the sleek bullets to shine for long-range varmint work, whether coyote calling, shooting distant jackrabbits or rockchucks, or those far pokes on prairie dogs and ground squirrels on a breezy day.

When loading, I used a Redding Premium Deluxe die set that includes full-length and neck-sizer dies along with a bullet-seating micrometer die. After initially shooting with the factory ammunition, I neck sized the cases that had been fireformed in the Remington chamber. The micrometer seating die makes working-up loads with multiple bullets a dream because a handloader can jot down the settings and return to that seating depth each time he returns to a specific bullet.

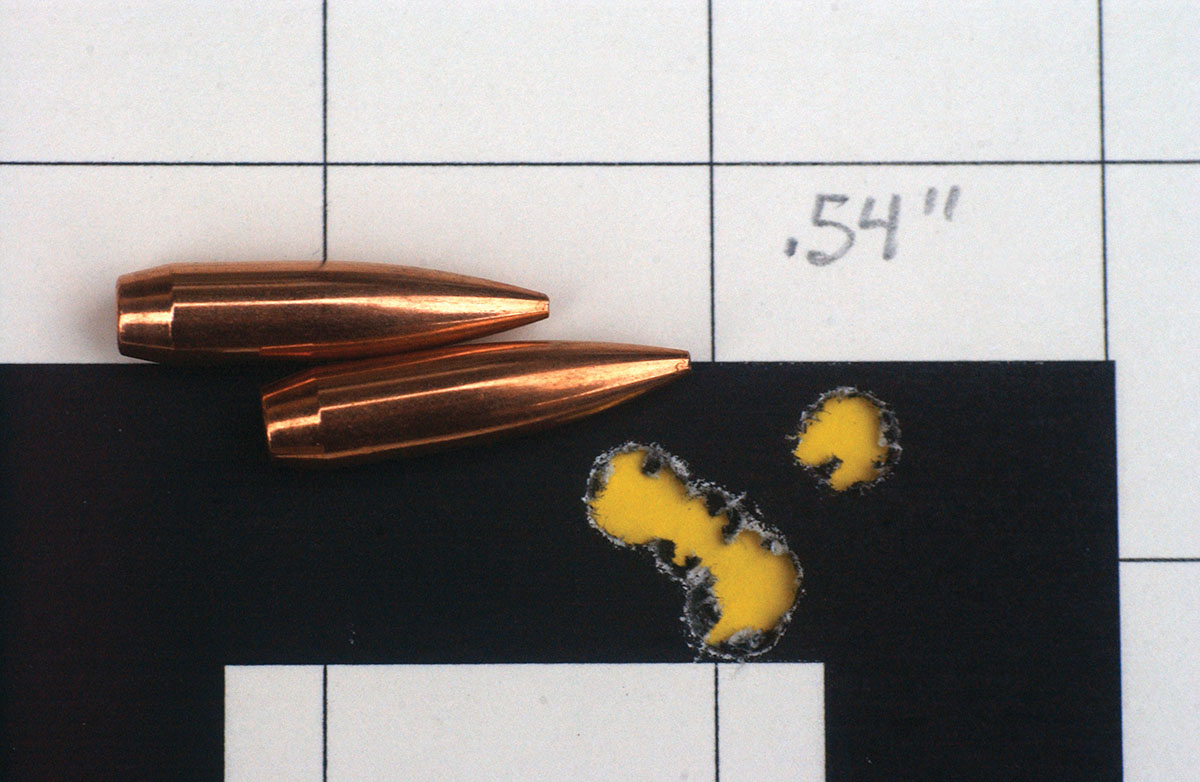

The load table shows the results of my brief testing. The best group shot with the rifle was a five-shot, .54-inch cluster made with the Sierra 100-grain MatchKing with a modest load of 55.5 grains of Vihtavuori N165 at 3,150 fps. The second-best load produced a .86-inch group with the Sierra 90-grain BlitzKing over 52 grains of Reloder 16 at 3,413 fps.

While this was a very limited test, it was pretty clear the rifle would shoot all of the bullets well with carefully worked-up loads. If I were going to just pick three or four powders to try, the two Vihtavuori powders – N165 and N560 – showed extreme velocity spreads of less than 30 fps in all loads tested, and groups were generally good. I would also use Reloder 16 and IMR-4451 for both consistency and near-maximum velocities with the heavier bullets in this caliber. If a handloader already has a good supply of IMR-4350 on hand, he would be hard-pressed to find a powder that was a lot better than this old standby that has been making this round meet its potential for over 50 years.

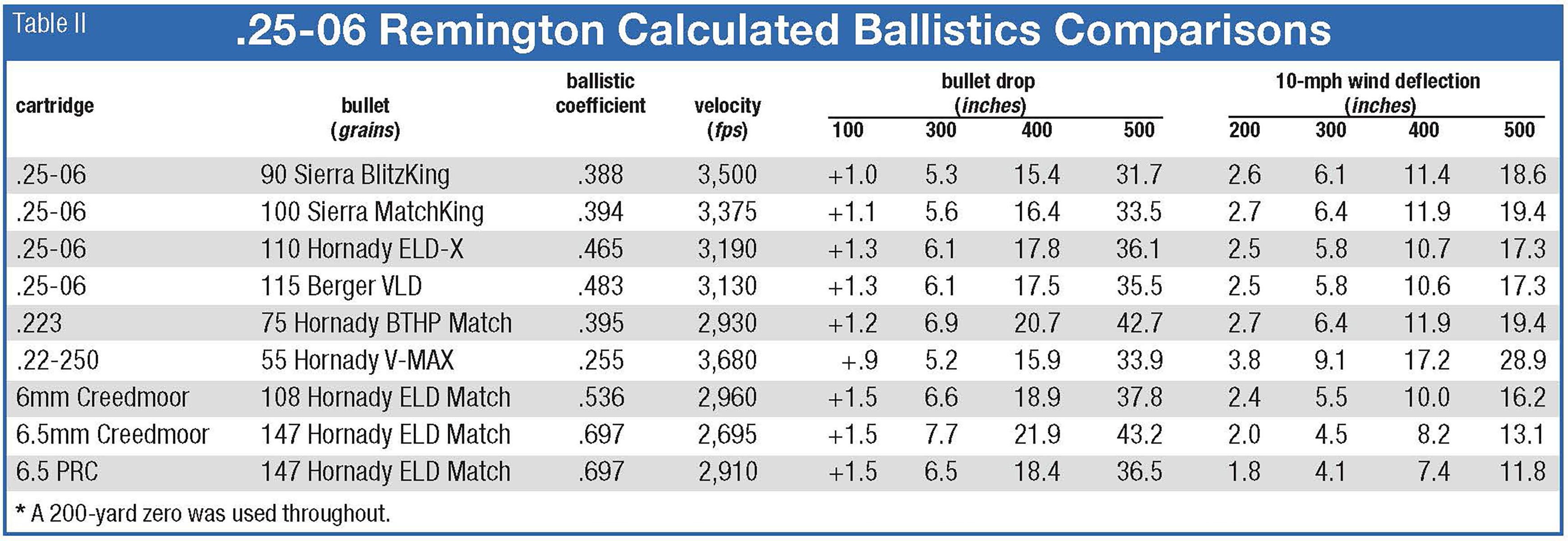

In the trajectory comparison table, I used loads for all four bullets tested. It compares the 25-06 Remington and 6mm Creedmoor, the 6.5mm Creedmoor and Remington’s 22-250 and 223 (with 75-grain bullets), and even the new 6.5 PRC. The comparison shows that until shots are taken at distances beyond where most of us shoot at varmints, velocity matters more than ballistic coefficient. If doubtful, look at the 22-250’s drop out to 500 yards with a bullet that has a .255 BC. The higher BC bullets are less affected by wind, but since wind is difficult to gauge in the field, most of us are really guessing on how much to hold into the breeze anyway, based on how the air feels on our cheek and years of experience missing long-range varmints in the wind.

jack sitting under a Joshua tree at a ranged 530 yards. I consulted the drop chart I’d made for the 100-grain Sierras and decided holding about a yard above its chest would be about right. But there was a brisk crossing breeze where we were sitting, and R.G. suggested holding about 2 feet into the wind. I thought 3 feet was better, but decided to split the difference.

The shot looked good when the trigger broke, but R.G. said the dust jumped up about a foot or more into the wind – I’d held too far into that breeze – but he reported the elevation was almost perfect for a chest hit. That rabbit took off at a lope and never stopped. When we dropped down off the little ridge from which we had been glassing, there was almost no breeze on the flat. The rabbit was lucky.

The bottom line is that the old 25-06 Remington still shines as a long-range varmint cartridge. If a company wanted to breathe new life into this veteran, it could make a couple of changes that would make it even more useful for true long-range shooting. Change the twist from the existing rate of 1:10 to something like 1:7 or 1:8, and then make super-sleek bullets that weigh 130 to 150 grains with BCs in the .700 range. Varmint shooters would really have something for those half-mile shots on breezy days.