Winchester's 25-20

Does it Still Have a Place in Varminting? Yes.

feature By: Art Merrill | October, 21

Winchester’s 25-20 is the progeny of the black powder 25-20 Single Shot target cartridge of 1889, an exceptionally accurate cartridge in its day. Winchester wanted to capitalize on the then-trendy 25-20 Single Shot, but rather than design a new lever-action rifle to fit the cartridge, the gunmaker duplicated the performance of the 25-20 Single Shot by necking down the already successful .32-20 Winchester to feed in its Model 1892 lever guns. Like its progenitor, the 25-20 earned a reputation for accuracy. Originally loaded with 17 grains of black powder, after the switch to smokeless powders, the 25-20 Winchester enjoyed significant popularity as a varmint and small-game cartridge before being displaced decades later by the likes of the 22 Hornet and 218 Bee.

There are plenty of old claims to bagging deer with the 25-20 and its 86-grain roundnose lead bullet loping along at about 1,500 feet per second (fps), but we don’t hear the stories about the wounded animals that got away. The 25-20 is not a deer cartridge; the 25-20’s natural prey is varmints and small game, and it’s natural habitat is the lever-action rifle. Ammunition manufacturers quickly settled on two roundnose or flatpoint bullets for the smokeless cartridge, first the aforementioned 86 grainer, and then a lighter 60 grainer.

But since Winchester’s 25-20 hit the hunting fields when buggy whips were still a good investment, does the 25-20 Winchester still belong among the ranks of varminters? People tend to assume varmint cartridges must be high-speed, flat-shooting affairs for reaching way out to wary predators or diminutive rodents, and for the most part, that is the description of today’s top choices. By far, the vast majority of our varmint cartridges send downrange bullets of .17, .22 and 6mm caliber. But not all varmint hunting requires cartridges boasting maximum speed and flat trajectories for long range. Some situations, such as the proximity of neighbors, prioritizes a comparatively quiet report and short distances, which is not the forte of most blistering centerfire varmint rounds. Rifles chambering the 25-20 also tend to be compact for easy carry. Those reasons are perhaps enough for many varmint hunters to take a look at the 25-20 for shorter distances.

According to The Book of Rifles (W.H.B. Smith and Joseph E. Smith, Castle Books, 1948), Savage introduced its bolt-action Model 23 series in 1923, chambering the Model 23A in 22 Short/Long/Long Rifle, the 23B in 25-20 Winchester, the 23C in .32-20 Winchester and the 23D in 22 Hornet. Production ceased in 1942, so the manufacture date for Ken’s rifle is sometime during that 19-year period.

Savage’s Model 23B is a bit deceiving, as its svelte stock and light 6.5-pound heft makes it feel as compact as a lever rifle; however, it is actually full-size with a slim, 24.5-inch barrel, 12.5-inch length of pull and overall length of 43 inches. The smooth, oil-finished stock appears to be walnut, showing some figure and sporting a conservative Schnabel forend. The 23B’s stamped steel magazine holds four rounds of 25-20, and the sights are standard for the period, a Williams- or Lyman-type gold bead front and a notched rear leaf with an elevation slide.

The bolt head is non-rotating, like that on Enfield SMLE and rimfire bolt guns, and like rimfires, the root of the bolt handle serves as a locking lug, camming the bolt forward into battery as the handle is lowered. There’s a second “safety” locking lug at the rear of the bolt, which engages a recess cut into the left wall of the receiver. While inferior in strength to dual front locking lug designs, the 23B’s simpler bolt is easier and cheaper to manufacture – a significant marketing factor during the Great Depression – and Savage found it strong enough to contain the normal working pressure of the Model 23’s short list of low-pressure cartridges.

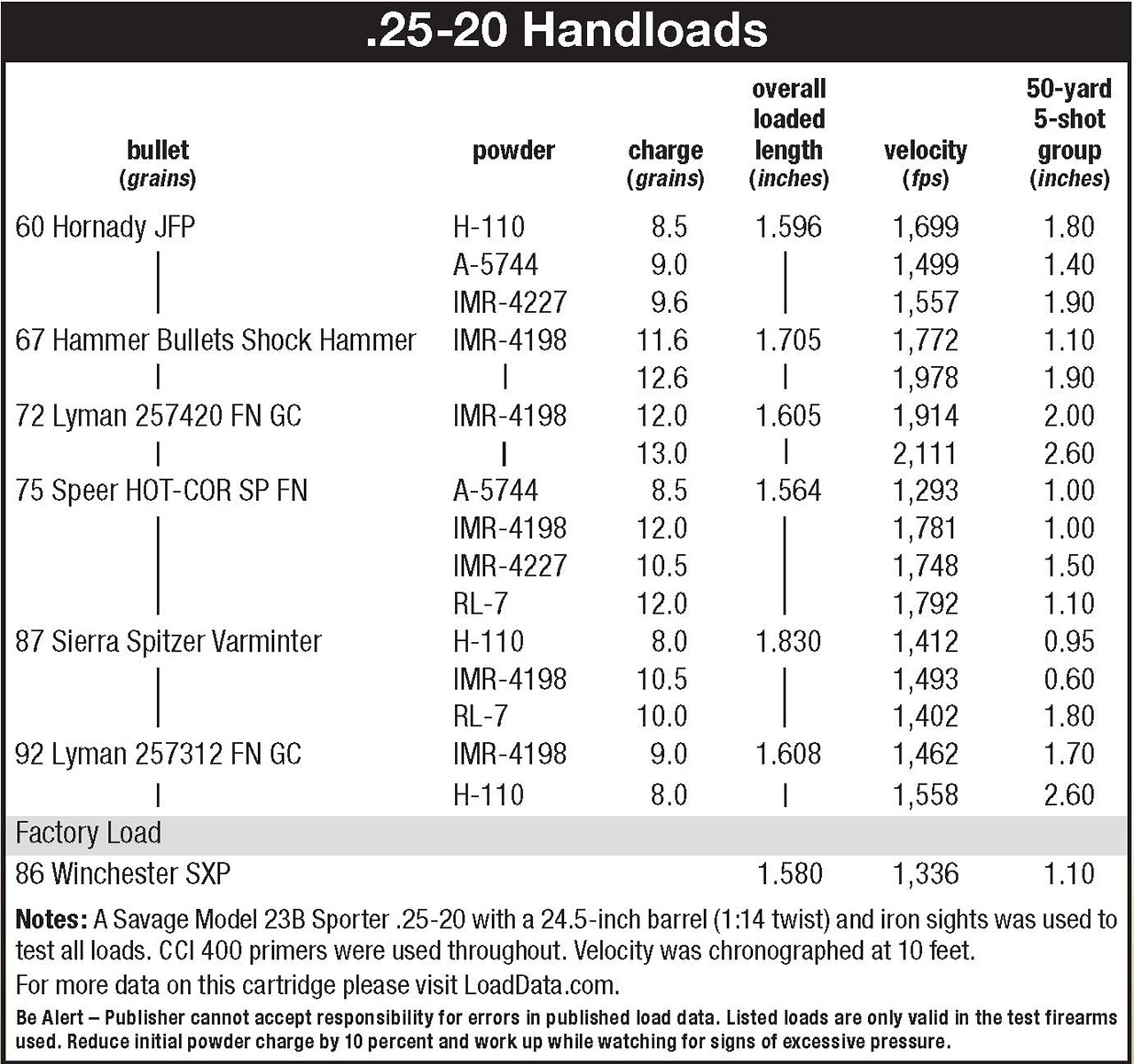

Acquiring bullets, powder, primers and even reloading dies in 2020 and thus far in 2021 has been a study in frustration for all handloaders. Bullets for the 25-20 from Barnes, Nosler and Remington were not to be had at any price in time for this report. A local gun shop had a couple boxes of Speer 75-grain Hot-Cor SPFN on the shelf, Hornady provided its 60-grain flatpoint bullet, Buffalo Arms still listed in-stock Sierra’s 87-grain Spitzer Varminter, and an online perusal turned up a new, unusual .257-inch, 67-grain lead-free copper hollowpoint spitzer Shock Hammer bullet from Hammer Bullets (hammerbullets.com).

As there is no 25-20 load data for a 67-grain bullet, some careful extrapolation from 71-grain bullet data was necessary. The Shock Hammer and Sierra bullets, of course, SHOULD NOT BE FED THROUGH A LEVER GUN’S TUBULAR MAGAZINE. As it turned out, both were also too long to feed loaded cartridges through the 23B’s box magazine, and required single loading.

Recent consumer demand has driven prices for nearly all factory cartridges into the “absurd” category – when they can be found at all. A “two-cups-of-coffee” online search finally turned up a 50-count box of Remington factory 25-20 Winchester loads at a retail cost of $90 plus shipping. While vacillating a few days on whether to order it, Ken picked up an old-stock box of Winchester Western X 86-grain Soft Points for $95. They are included here as a factory cartridge baseline performance reference.

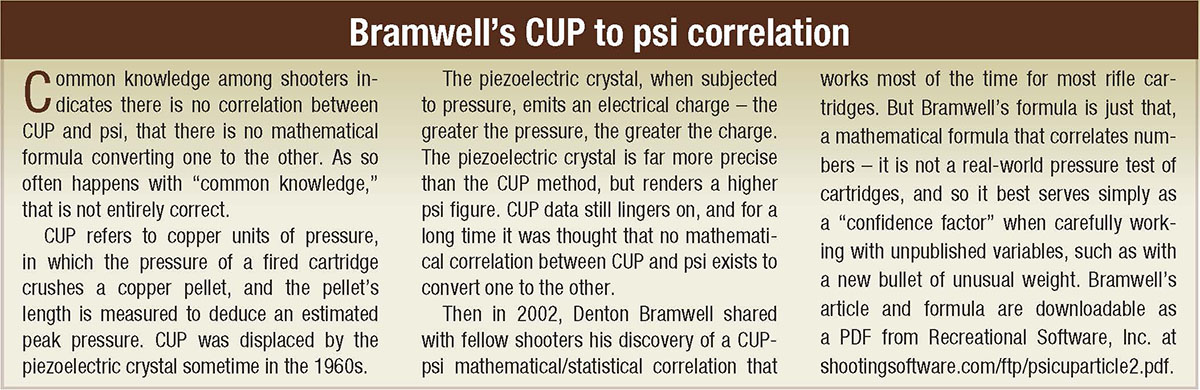

Operating pressure for shooting the former black-powder cartridge in lever guns is quite low. Ken Waters (Ken Waters’ Pet Loads, Wolfe Publishing, 1999) mentions 22,000 psi with 17 grains of black powder pushing 86-grain cast lead bullets at 1,376 fps, and 27,000 psi to 30,000 psi for smokeless powder with 86-grain jacketed bullets started at 1,732 fps muzzle velocity. Given that Waters apparently wrote his article about 1975, I can assume he means copper crusher-measured CUP psi, not piezoelectric-measured psi. The Speer Reloading Manual #14 (2007) stated 26,000 CUP is the “industry standard” but the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) manual’s entry for maximum pressure for the 25-20 Winchester is actually “N/E” – Not Established. SAAMI’s European equivalent, Permanent International Commission (CIP) for the Proof of Small Arms is more helpful, establishing 2,700 bar (39,160 psi) as maximum (Pmax) for the cartridge. The CIP pressure is piezoelectric psi, not CUP, so is rendered as a higher figure.

In addition to the Lee, Lyman, Speer and Hornady manuals, handloaders can find online load data for the 25-20 Winchester at loaddata.com and hodgdonreloading.com. Most of these sources list the same Hodgdon and IMR powders for the 25-20 found in old loading manuals, but Speer includes Vihtavuori N110. Five powders show up consistently in cast and jacketed bullet load data for the 25-20 – Unique, Alliant 2400, H-110, IMR-4227 and IMR-4198. On Hodgdon’s burn rate chart of 163 powders, Unique (a pistol powder) falls at number 32 as the fastest and IMR-4198 (a rifle powder) at number 75 as the slowest for the cartridge. Another 41 potential powders, some of them comparatively new, lie in between to offer plenty of opportunity for individual exploration.

For cases, I augmented Remington’s “R-P” brand with 60 more purchased new online from huntingtons.com and headstamped, “LX.” All were resized, trimmed and chamfered before reloading. The LX case primer pockets needed a bit of deepening with a primer pocket uniforming tool to be sure the CCI 400 primers seated fully. RCBS full-length resizing and seating dies did the honors; all seated bullets got the same light crimp. I weighed individual charges on a balance beam scale.

Though the hope here was to perhaps wring MOA accuracy at 2,000 fps or a bit more from the cartridge and the Savage’s 1:14 twist rate; even though cases and primers showed no overpressure signs at 2,050 fps, the trend was that accuracy generally suffered as velocities increased beyond 1,600 fps. In accuracy testing at 50 yards, only one load showed MOA accuracy, with Sierra’s 87-grain Spitzer Varminter and IMR-4198. The Sierra bullet also came in second in group size at .95 inch with IMR-4198 again. The Shock Hammer bullet printed a 1.1-inch group at 1,772 fps, but stepping up the velocity another 200 fps doubled group size. Other combinations grouped from 1.5 to 2-plus inches; extrapolating that out to 100 yards renders a theoretical 3 to 4 MOA. Among cast bullets, the Savage had a proclivity for the lighter 72-grain bullet, which turned in a 1.3-inch group at a respectable-for-lead 1,657 fps. Again, all groups were fired at 50 yards.

An interesting comparison did come up. The Lyman Reloading Handbook 44th Edition (1967), lists a “Factory Duplicate Load” of 10.5 grains of IMR-4198 launching an 86-grain jacketed bullet at 1,283 fps. In this exercise, Sierra’s 87-grain jacketed bullet pushed at 1,493 fps by that same 10.5 grains IMR-4198 produced the smallest group, .60 inch. That $95 box of Winchester factory ammunition shot a 1.1-inch group with an average muzzle velocity of 1,336 fps. The factory duplicate load way outperformed the actual factory load.

To be fair, I will admit that I do not shoot my best with barrel mounted iron sights (a reason for testing at 50 rather than 100 yards), even firing from a heavy benchrest with sandbags; another shooter or some scope magnification might have shrunk groups a bit. However, given the 25-20’s short working range, the reality is that most shooters wouldn’t use a scope, so the iron sight accuracy testing was realistic. I had only a handful of the Shock Hammer bullets to work with; if I were to continue load development, I would delve deeper into the Hammer’s potential even though the heavy Sierra bullet appears to show the greater promise so far.

Granted, such nineteenth-century performance is hardly stellar compared to what we get from modern varmint rifles and cartridges. Shooting small varmints at distance calls for a sub-MOA rifle/cartridge combination; the accompanying table shows that the 25-20 Winchester in this old Savage is not up to long range varminting, though the potential for MOA at 100 yards, and perhaps a bit further, is there. But small critters and long-range rifles aren’t the only games in “Varmint Town,” as an elderly lady rancher in my area finds the M1 Carbine and its .30-caliber pistol cartridge just dandy for dealing with coyotes.

While several popular varmint cartridges are the work of independent wildcatters of the 1930s through the 1960s and subsequently legitimized as factory cartridges, the 25-20 Winchester is from a different family – target shooting – and a different era. It survived the shift from black to smokeless powder and benefited from newfangled jacketed bullets. Though long eclipsed by newer cartridges with far more reach, it perhaps hangs on due to the quality firearms for which it was chambered and that still occupy rifle racks, and for its mild report, easy reloading, small appetite for powder and adequate short-range accuracy. For these reasons, it still has a place in varminting.