The ageless 22 LR cartridge was used on this ground squirrel crouched on a downed log at the Tejon Ranch.

A couple of acceptable 100-yard groups with the Winchester Model 94 17 HMR using CCI 17-grain ammunition.

As a kid, I firmly believed there was only one rifle worth having: a Winchester lever action. At the time, I had no clue as to how many different lever-action rifles Winchester made, nor did I care. It just had to be a lever action because that’s what all the cowboy heroes carried in movies and television shows. Being one of those lucky kids that had access to some open land for small-game hunting, my only stipulation was that it had to be chambered in 22 Long Rifle. Alas, Winchester didn’t make such a gun, and while I settled for other .22 rifles over the next half century, including Marlin’s excellent Model 39, I was never quite satisfied.

When Winchester finally realized my dream remained unfulfilled, the company assembled its engineers and manufacturing personnel to make things right. As it turned out, the result was a bonanza. In the intervening years since my youth, both the 22 Magnum and 17 HMR were added to the inventory of rimfire ammunition and Winchester decided to make my lever action in all three calibers. Unfortunately, its production lines only remained open for a very short time, and it took me another 15 years to find and acquire all three rifles.

Once the Picatinny rail is trimmed to size, this is a pretty useful sight arrangement for a lever-action 22 Winchester Magnum. The accessories that come with the Bushnell sight make both installation and removal simple and quick.

All three rifles are very similar with a couple of noteworthy differences. The 17 HMR features a 22-inch barrel and a curved lever while the two .22 calibers are equipped with 20-inch barrels and straight levers/stocks. All three have glassy smooth actions, smoother than any other lever-action rifle I’ve ever used. I love them all! The 17 HMR and 22 LR have hard, glossy finishes like the varnished rails on expensive sailboats, but the 22 Winchester Magnum has a softer, oil-based finish. The glossy finish looks fantastic and makes those two guns look like show pieces to display for visiting friends to incite envy. Unfortunately, any bump that chips the finish also becomes a “show piece” and is difficult to repair. The oil finish on the 22 Magnum states this is a “shooter’s rifle” meant to be carried afield and used. Dings and chips are much easier to repair. I use all three guns for varmint hunting; I just have to be a little more careful with the two highly-polished finishes.

All three rifles have the integral slots on top of the receiver for the old-style, clamp-on scope rings used on rimfire rifles for years, rather than the bulky Picatinny rails currently favored in today’s tactical dominated market. There is no problem for the 17 HMR, since I immediately topped it with a slender, lightweight 1.5-5x variable power Leupold scope. With the .17 caliber’s 2,500 feet per second (fps) ammunition and flat trajectory, this is a rifle that can reach past 100 yards in the hands of even a mildly serious shooter. At these ranges, the 5x setting provides a serious performance boost, although my default carry position is between 2x and 3x for quicker target acquisition. If I crawl the stock at 5x, my field of view shrinks and I usually waste some time searching through a restricted “tunnel” for the desired target.

A big log isn’t exactly like going prone at Camp Perry, but it gets the job done!

My plan for the smaller .22-caliber Winchester was to equip one with a zero magnification red dot optic, as I’ve done with several hunting handguns and a couple of rifles. I’ve found red dots to be faster than a scope on a rifle, and definitely an advantage over iron sights with my aging eyesight. Unfortunately, most smaller red dots are marketed toward a handgun while the larger ones come ready for mounting on an AR rifle equipped with a tactical type of rail. Fortunately, the Bushnell RXS-250 Reflex Sight (red dot) comes with an adaptor plate that will clamp directly on a Picatinny rail. The problem was finding an aftermarket adaptor that would handle the transition from red dot to rifle without having to drill and tap the Winchester receiver. A phone call to Finks Custom Gunsmithing at Gunsite resulted in a fairly short “adaptor” that features a small base clamp and fits the integral rails of the Winchester rifles with a short Picatinny rail on top to accept the Bushnell’s adaptor plate. The Picatinny rail is longer than needed for a red dot, so I’m planning to cut it to a shorter length that is flush with the edge of the RXS-250 sight. The end result will be a relatively compact mounting system that keeps the line of sight close to the bore axis.

The Tejon Ranch encompasses thousands of acres of land in the foothills and mountains north of Los Angeles. It’s home to elk, deer, wild hogs, and one of Dick’s favorite animals, ground squirrels.

Initially, I had a small concern that the Bushnell’s 4-MOA dot reticle would be a little large for varmint shooting. In practice, using Bushnell’s brightness control pretty well deals with the dot size. Shooters can change the brightness of the dot to deal with various ambient light conditions; going brighter for a sunny day or dimmer for cloudy conditions effectively changes the dot size. If it’s too bright, the glare overwhelms the target’s visibility: too dim and I can’t find the dot. It works for me, plus I really appreciate the little “tool kit” and cleaning cloth that comes with the RXS-250 sight.

Bring your own sandbag and occasionally you can use your truck as a benchrest.

In a walkabout field trip, all three rifles are simple to operate quickly. When using a rest (as in doing the accuracy tests), there were a couple of occasions where my hand and the lever struck the bench prior to full-length travel of the lever. This resulted in the ejection of the fired case, but a failure of the new cartridge to feed. Nothing jammed, but when I closed the action and pulled the trigger, I was greeted by a metallic “click” instead of the anticipated “bang.” Fully cycling the action brought up the next round and I was back in action. I’ve heard the cowboy action shooters call it “short stroking,” and it can happen if you’re trying to go too fast or if there is something that interferes with your lever stroke. In my case, it was my hand hitting the hood of the truck on which I was resting the rifle. No worries for a right-handed shooter. Simply rotate the gun 90 degrees counter clockwise so the ejection port is pointed up and run the lever. The guns will cycle in a horizontal position for right-hand shooters. I can’t guarantee that for lefties who have to rotate the gun clockwise.

Leupold’s little 1.5-5x scope has worked beautifully for years on the Model 94 17 HMR. Due to limited real estate space between scope and hammer, care must be taken in cocking or de-cocking the hammer.

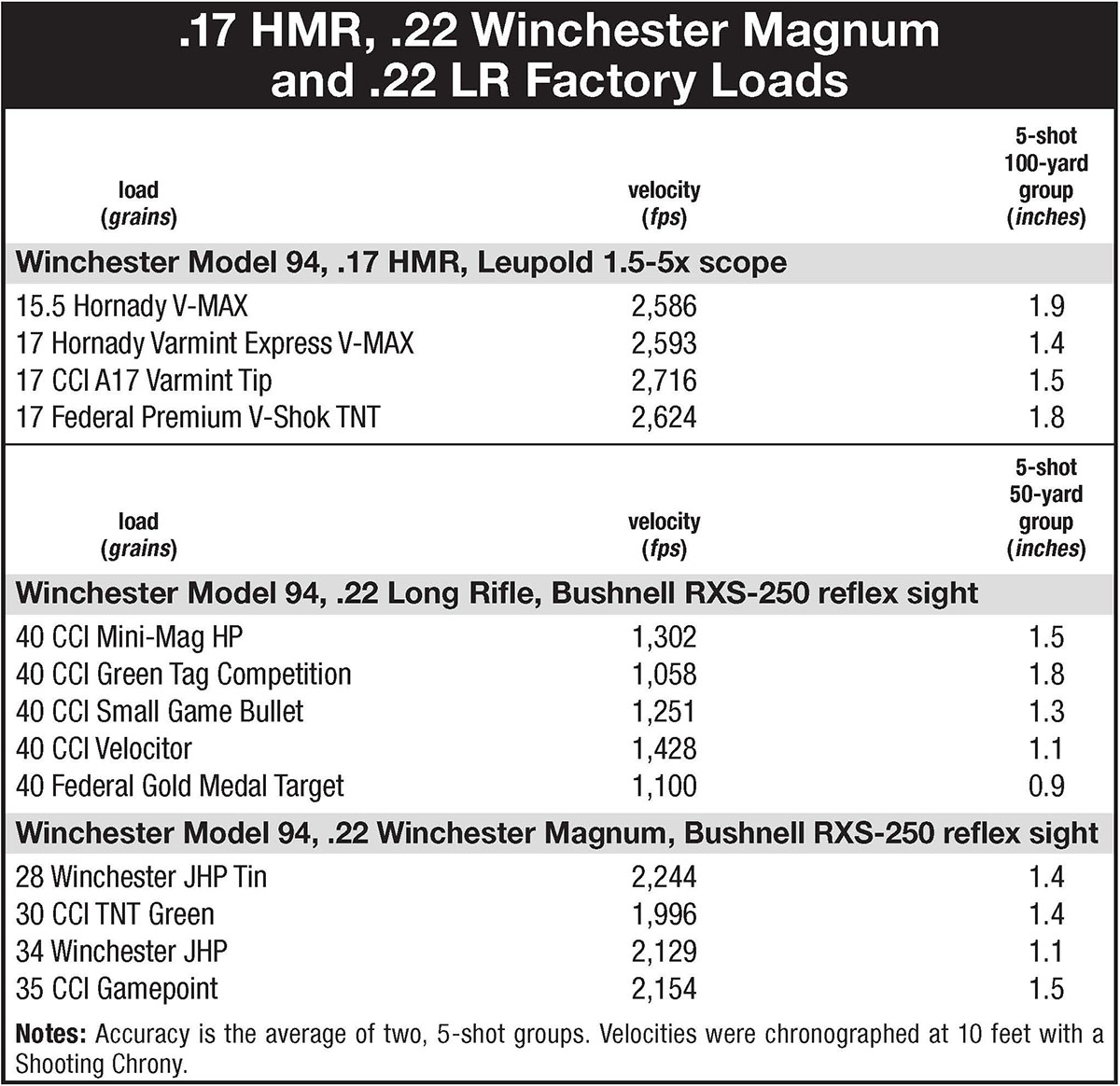

These are not benchrest rifles, nor did I expect them to be. Trigger pull weights on all three guns were about the same. Specifically, the 17 HMR averaged 3 pounds, 15 ounces, the 22 LR went 4 pounds, 2 ounces and the 22 Magnum averaged 4 pounds, 4 ounces. I expect that dedicated “one-hole shooters” would be horrified by these numbers, but for me 4 pounds is a great weight because that’s what most of my hunting handguns run when fired in single action. As in any serious endeavor, the best performance usually comes from doing what you’ve trained to do; in my case, that’s pressing 4-pound triggers thousands of times in a lifetime of shooting.

In addition, as I get older, I can’t go as far nor carry the same size loads I once did. A lighter rifle helps reduce weight, plus it makes for improved handling characteristics. The rifle moves more quickly and gets on target faster. If hunting with a rimfire caliber, a hunter has already made the decision to pass on longer range shots. Once a target has been spotted, the stalk is on. If your 5-pound rifle only produces 2-MOA groups instead of the .5 MOA delivered by a 12-pound bolt gun, any target 100 yards or closer is still viable game. With a load that will give me something like 2-inch groups, I can happily hunt varmints all day long even knowing my hit rate will not be as high.

Once properly sighted-in, this 22 Winchester Magnum group was fired at 50 yards.

Reloading the magazine tubes on the Winchesters is considerably more involved than on a rifle using detachable box magazines. Instead of simply slapping in a new, pre-loaded magazine, a hunter must hold the rifle with the muzzle pointed upward, release the latch on the spring-loaded magazine tube, pull the tube out of the gun until the loading port is exposed, then hold it in place while inserting individual rounds of ammunition into the port. Gravity will pull the ammunition down into the gun. When the last round fails to drop all the way down and partially blocks the loading port, reinsert the removable tube all the way, rotate the latch into the locked position and get on with the day’s shooting. The magazine tubes on both the 17 HMR and 22 Magnum hold 11 rounds and the 22 LR holds 15 rounds. Do not cycle the action and try to “top off” with one more round. This will be “muzzling” a cocked rifle.

Access to the hammer in the event a shooter needs to manually cock or de-cock the rifle is more difficult on the 17 HMR because the scope extends rearward over the hammer, leaving very little space for the thumb. This is not so with the Bushnell dot scope, which is mounted further forward over the action. When hunting with scoped, single-shot handguns, I use to attach an aftermarket spur to the hammer that extended off to the side, either left or right, and allowed easy access and operation of the hammer by the thumb. As always, be careful operating any firearm.

I still have a couple of very serious, long-range varmint rifles that I use when the shooting involves putting out benches on the edge of a large prairie dog town, but during a re-cent visit to Tejon Ranch, where the local rodent population is composed of ground squirrels scattered among oak trees and open fields and the opportunities are usually 100 yards or closer, rimfires will take a rifleman back in time and remind him of the great days he had as a kid. For me, the three Winchesters are like a decade’s late birthday presents that I dreamed of as a kid.